Abstract

Training primary care providers to incorporate a youth development approach during clinical encounters with young people represents an opportunity to integrate public health into primary care practice. We recommend that primary care providers shift their approach with adolescents from focusing on risks and problems to building strengths and assets. Focusing on strengths rather than problems can improve health by fostering resilience and enhancing protective factors among adolescents. A strength-based approach involves intentionally assessing and reinforcing adolescents' competencies, passions, and talents, as well as collaborating with others to strengthen protective networks of support for young people. Training programs should incorporate interactive strategies that allow clinicians to practice skills and provide tools clinicians can implement in their practice settings.

Promoting healthy youth development helps ensure that young people can thrive through the mundane and extraordinary events of adolescence.1 Youth development approaches represent a type of public health activity that involves a deliberate process of providing all young people with the support, relationships, experiences, resources, and opportunities they need to become successful, competent adults.2 These approaches seek to achieve 1 or more of the following objectives:

Promote bonding;

Foster resilience;

Promote social, emotional, cognitive, or behavioral competence;

Foster self-determination;

Foster spirituality;

Foster self-efficacy;

Foster a clear and positive identity;

Foster belief in the future (i.e., hope and optimism about personal possibilities);

Provide recognition of positive behavior;

Provide opportunities for prosocial involvement;

Foster prosocial norms.3

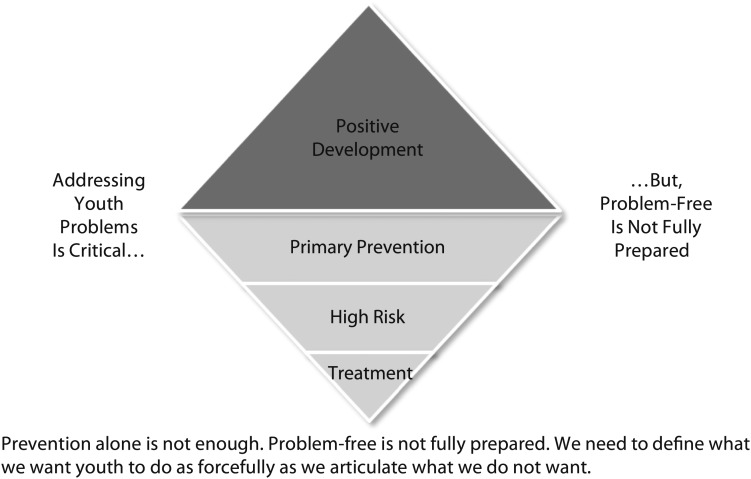

Strategies that promote healthy youth development broaden the traditional public health model that defines everything in terms of a problem: (1) define the problem, (2) identify risk and protective factors, (3) develop and test prevention strategies, and (4) ensure widespread adoption.4 Ultimately, we assess people on the basis of potential, not the presence or absence of problems.5 Therefore, prevention constitutes an important, yet inadequate goal because “problem-free is not fully prepared, and fully prepared is not fully engaged.”5(p17) Figure 1 presents Pittman et al.’s5 graphic presentation of how we can build on the public health model of prevention activities to promote strengths, assets, and protective factors that facilitate healthy youth development. Primary care providers (PCPs) can serve as important partners with families, schools, and community agencies to foster healthy youth development by balancing the goals of preventing problems, promoting development, and encouraging engagement among all their adolescent patients.

FIGURE 1—

Beyond prevention: how we can build on the public health model of prevention activities to promote strengths, assets, and protective factors that facilitate healthy youth development.

Source. Available online at http://www.forumfyi.orgreproduced with permission from K. Pittman.5

A strength-based perspective on youth development represents a paradigm shift in adolescent health care that invites us to train PCPs to approach clinical encounters with young people from this type of public health mindset.6 The leading causes of morbidity and mortality among adolescents relate to preventable conditions such as obesity and inadequate physical activity, use of tobacco and other substances, high-risk sexual behaviors, mental health problems, and injury and violence.7 Rather than focusing on risk reduction (e.g., reducing the outcome of adolescent pregnancy by developing resistance skills among young people at risk for early onset of sexual activity), we can teach clinicians to build on individual strengths and address factors that predispose a young person to multiple risks (e.g., school failure, adult mentorship).8 Youth development programs focused on surrounding young people with protective factors or resources in their social and environmental ecologies may achieve greater improvements in outcomes than those focused on minimizing risk.9,10

Clinicians can help integrate public health into primary care by embracing the principles of youth development when providing direct health care services to adolescents. Primary care providers applying principles of youth development in their clinical encounters intentionally assess positive features of development in young people and their environments. They subsequently build developmental assets, such as those articulated by Benson,11 associated with future success and reduced involvement in risk behaviors. Assets and protective factors work in the lives of all young people by promoting healthier choices and avoidance of risk behaviors, as well as by fostering more positive outcomes and resilience when young people face negative experiences.6

PROMOTING HEALTHY YOUTH DEVELOPMENT IN CLINICAL ENCOUNTERS

Traditionally, Western medicine focuses on screening for pathology and subsequently establishing treatments for identified pathologies. Many PCPs approach encounters with adolescents from a risk-centered, problem-focused perspective that propels them to mine for disaster in young people’s lives. Therefore, the most basic and essential philosophical shift involves how PCPs personally view, interact with, and advocate for young people.12 Primary care providers focused on promoting healthy youth development perceive adolescents as possessing competencies, passions, and talents a clinician can identify and enhance. They view adolescents as capable of making important contributions while requiring support, mentoring, and opportunities, as opposed to viewing young people as problematic and needing solutions designed and imposed on them by adults.12 Groups vulnerable to poor health may prefer this solution-oriented approach, which emphasizes assets rather than restating pathology. Thus, a youth development approach represents a promising strategy to create health equity among adolescents.10

Focusing on strengths does not negate risks. Instead, this perspective attempts to provide balance and hope.12 An assessment of a young person’s assets recognizes and fosters innate strengths to promote resilience and improve health.1 The American Academy of Pediatrics supports the use of strength-based approaches in clinical encounters with adolescents. Diverse frameworks and structured questionnaires, such as Bright Futures13 and Connected Kids,14 may help clinicians incorporate a systematic approach to identifying strengths.15,16

Administering a questionnaire to adolescents during their wait to see a PCP can help address time constraints. Providers can use the instrument to quickly examine information about assets at the beginning of an appointment, allowing them to direct further assessment and counseling appropriately. The box on the following page provides sample questions PCPs can ask adolescents to elicit additional information about strengths and indicators of healthy development. A strength-based approach attempts to raise adolescents’ awareness of their strengths and motivate them to accept responsibility for their role in maintaining their personal health and well-being.15 Follow-up interactions should reinforce identified strengths and help foster areas that may need enhancing. Clinicians can use identified strengths to facilitate a discussion about needed behavior change, possibly through motivational interviewing—a collaborative, person-centered style of eliciting and strengthening motivation for change.17 Research demonstrates positive behavior change among adolescents engaged in motivational interviewing.17 Discussing strengths in general and as part of motivational interviewing reinforces for young people the need to actively seek out and acquire the personal, environmental, and social resources required for future success.15

Implications for Primary Care Providers and Sample Questions They Can Ask Adolescents to Elicit Additional Information About Strengths and Indicators of Healthy Development

| • Approach adolescent patients with a belief that they possess strengths, capacities, and talents a clinician can identify and enhance. Remain nonjudgmental and practice active listening. |

| • Intentionally elicit and reinforce strengths, assets, protective factors, and indicators of healthy youth development while conducting a psychosocial interview. |

| Sample questions: |

| Who do you get along with best at home and why? |

| Who are your friends? What do they like best about you? |

| What do you love to do? |

| What are you really good at? |

| What do you do well at school? |

| What do you want for yourself, now and in the future? |

| What do you do to help others? |

| Whom do you go to when you feel sad or have a problem? |

| What adults in your life provide you with support and guidance? |

| Who is crazy about you? |

| Who is happy for you when you do something well? |

| • Educate parents about strengths, and help them identify and foster protective factors in their children’s lives. Encourage parents to remain involved in their child’s life, and teach them how to support and connect with their adolescent. Make referrals and facilitate connections to parenting programs and other community resources, when appropriate. |

| • Provide anticipatory guidance about normal adolescent development and potential difficulties. Discuss ways to avoid or handle difficult situations, facilitate development of healthful coping strategies, foster problem-solving skills, and cultivate caring relationships and social networks. |

| • Collaborate with families, teachers, guidance counselors, social workers, mental health specialists, community organizations, and others to support adolescents, facilitate connections with prosocial adults, provide challenges and opportunities to contribute, and promote healthy youth development. |

Primary care providers who approach their care of adolescents from a youth development perspective seek opportunities to enhance their own knowledge and establish strong safety nets for their patients by collaborating with individuals within and outside the health care system. Collaboration constructs a referral network for adjunct care, creates connections with resources in the community, builds relationships with primary support persons for adolescents, extends the reaches of health promotion outside the office, augments contextual understanding of adolescents’ experiences, and may enhance cultural competency.1 Implementing a youth development approach to encounters with adolescents provides clinicians with tools to work more effectively with families, schools, and other support systems in young peoples’ lives.6

Collaborating with families and other nonfamilial, caring adults by recognizing their strengths and recruiting them to assist in adolescent health promotion creates powerful allies, while facilitating family connectedness and resilience among young people.1 These partnerships synergize efforts to help young people learn and develop across a range of developmental areas.5 Evidence-based parent education programs demonstrate effectiveness in improving parent–child connectedness and reducing behavioral problems.18 The primary care–based intervention of Borowsky et al.19 illustrates the effectiveness of integrating a public health approach into primary care by collaborating with parents and parent educators to promote family level protective factors. In this study, children of parents who participated in a parenting education program demonstrated decreases in problem behavior compared with a control group. Primary care providers should inform parents about the availability of effective programs in their area and facilitate access.

Furthermore, clinicians should create opportunities during their time with parents to educate them about strengths and help them identify and foster protective factors in their children’s lives.20 Clinicians can build parents’ communication skills, provide them with information about adolescent development, and enhance their sense of influence on and significance in the lives of their adolescents.12 Using motivational interviewing techniques with parents in primary care settings shows effectiveness in changing parental behavior.21 Discussions with parents and adolescents together provide opportunities for PCPs to model positive ways parents should talk with their children about what is going right and highlight a child’s strengths.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR TRAINING

Training and continuing education programs for PCPs can integrate public health into primary care by providing opportunities for clinicians to learn about positive youth development as a type of public health activity. Such training may occur within a behavioral health rotation during medical school, a seminar session or module before continuity clinic or within an adolescent medicine rotation during residency, and a continuing education workshop for clinicians in practice. Collaborating with public health professionals, including health educators and experts in motivational interviewing, to develop and implement training programs would offer PCPs opportunities to learn from individuals with significant knowledge about the field of public health.

Furthermore, these programs should include exercises that allow clinicians to critically evaluate their perceptions of adolescents and explore how they may incorporate a strength-based, asset-building approach in their care of young people. Primary care providers need occasions to acquire and practice skills necessary to cultivate meaningful connections with adolescents that create opportunities to promote healthy youth development. Adolescents remain highly attuned to authenticity and sincerity in interactions with adults, and they will detect signals that clinicians do not really care.6 A health care provider’s interpersonal style remains paramount to connecting with adolescent patients. Specifically, young people respond to PCPs whom they perceive as trustworthy, with a caring and positive attitude.22 Creating positive connections with adolescent patients requires that PCPs remain present and nonjudgmental, give young people their full attention, and engage in active listening while appreciating adolescents’ insights and motivations. The foundation of powerful therapeutic connections and successful interventions resides in understanding the context of adolescents’ lives and their perceptions of their experiences. Clinicians require opportunities to practice communicating with adolescents using techniques that facilitate a conversation. Because of time constraints, PCPs can easily become locked into a closed-ended mode of questioning that limits opportunities to understand fully an adolescent’s experience. Therefore, clinicians need to learn about and practice engaging young people with open-ended communication techniques that allow patients to discuss their goals and experiences.

Research shows the effectiveness of interactive versus passive educational activities in changing clinician behavior.23 Developers of training programs that teach PCPs how to promote healthy youth development should incorporate interactive methods that reinforce learning and enable clinicians to practice new skills. For example, role-playing with standardized patients (i.e., actors trained to portray a patient for teaching purposes) allows clinicians to practice connecting with adolescents, identifying protective factors, reinforcing personal strengths, cultivating problem-solving or coping skills, facilitating connections to prosocial adults, and creating opportunities to contribute. Incorporating standardized parents into role-playing exercises would further enhance training experiences by enabling clinicians to prepare for opportunities to discuss normal adolescent development and the concept of resilience, identify strengths within the family, suggest ways to enhance protective factors and reinforce their children’s assets, and, if necessary, improve parenting skills associated with healthy youth development. Providing clinicians with tools that help them implement knowledge and skills also reinforces learning.23 In addition to a structured questionnaire or interview framework, PCPs can develop a list of resources related to adolescent development and resilience they learn to offer parents and adolescents during clinical encounters. Such a list may include the Search Institute’s Parent Further Web site24 as well as the American Academy of Pediatrics adolescent health Web site.25

Facilitated, interdisciplinary discussions within training programs provide avenues to share knowledge about community resources and potential partnerships. Clinicians would benefit from guidance on establishing and maintaining collaborative relationships that enhance resources for adolescents and strengthen protective networks of support that promote healthy youth development. Pediatric PCPs indicate that barriers to making referrals to community agencies include lack of knowledge about and insufficient resources in their area, long waiting lists, and patient insurance limitations.26 Collaborating with public health professionals to administer training programs could address barriers, enhance referral networks, and extend clinicians’ efforts to promote healthy youth development outside the confines of the primary care setting.

CONCLUSIONS

Approaching clinical encounters with adolescents with intent to identify and enhance individual strengths, talents, or achievements represents a novel construct in Western medicine’s traditional clinical realm of pathologizing behaviors and assessing risk.1 This paradigm shift toward perceiving adolescents as having resources and skills, strengths rather than weaknesses, and resilience despite vulnerability requires accompanied changes in approaches to education and training in adolescent health care.6

Still, organizational changes likely need to supplement education initiatives to ensure that clinicians have the resources and supports required to promote healthy youth development in primary care. For example, clinics can address time constraints by administering structured questionnaires that assess assets and protective factors in adolescents’ lives to direct a PCP’s attention to sources of strength and potential problem areas. In addition, leveraging resources offered by communities, nurse coordinators, and colocated mental health and social services would extend services PCPs could provide during their brief encounters with adolescent patients. Incorporating a program such as Health Leads27 that trains college students to connect patients to resources that meet basic needs, as well as to foster strengths and promote resilience also would reduce some burden on busy PCPs. With organizational and administrative support, PCPs can help young people capitalize on their strengths and turn challenges to their advantage.12 Furthermore, clinicians can build on the basic public health model by offering or facilitating access to services, supports, and opportunities that help ensure that all young people become problem-free, fully prepared, and completely engaged.5

Educators developing training programs for PCPs should collaborate with public health professionals. Training curricula should address positive youth development as a public health activity, role of protective factors, and means of approaching interactions with adolescents from a strength-based perspective. Programs should include interactive techniques, such as role-playing, that enable clinicians to practice connecting with adolescents; provide opportunities for clinicians to reflect on and discuss their perceptions of adolescents and approach to clinical care of young people; and offer guidance on accessing resources and collaborating with families, schools, and community agencies. Future research should evaluate the impact of incorporating systematic approaches to identifying strengths and facilitating healthy development in primary care on health outcomes among adolescents. Providing clinicians with knowledge and skills to foster healthy youth development represents an important opportunity to integrate a public health approach into primary care practice, and a promising strategy to address critical public health problems that contribute to morbidity and mortality among adolescents.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cooperative agreement 5U48DP001939).

We would like to thank Nimi Singh, MD, MPH, Chinwe Umez, MD, and Erin Pratt, MA, LPC, for providing insight on how to incorporate a strength-based, resilience perspective during clinical encounters with adolescents.

Note. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Human Participant Protection

Human participant protection was not required because this review of the literature did not involve human participants.

References

- 1.McManus RP., Jr Adolescent care: reducing risk and promoting resilience. Prim Care. 2002;29(3):557–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center for Youth Development and Policy Research. What is youth development? 2002 Available at: http//cyd.aed.org/whatis.html. Accessed June 22, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catalano R, Berglund M, Ryan J, Lonczak H, Hawkins J. Positive youth development in the United States: research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2004;591(1):98–124 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Violence prevention—the public health approach to violence prevention. 2008. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/overview/publichealthapproach.html. Accessed June 5, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pittman K, Irby M, Tolman J, Yohalem N, Ferber T. Preventing Problems, Promoting Development, Encouraging Engagement: Competing Priorities or Inseparable Goals? Washington, DC: The Forum for Youth Investment, Impact Strategies Inc; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saewyc EM, Tonkin R. Surveying adolescents: focusing on positive development. Paediatr Child Health. 2008;13(1):43–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreipe R, Ryan S, Seibold-Simpson S. Principles for youth development. : Hamilton SF, Hamilton MG, The Youth Development Handbook: Coming of Age in American Communities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2004:103–126 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blum RW. Healthy youth development as a model for youth health promotion: a review. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22(5):368–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eccles J, Gootman J. Community Programs to Promote Youth Development. Washington, DC: National Research Council, Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Resnick MD. Healthy youth development: getting our priorities right. Med J Aust. 2005;183(8):398–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benson P. 40 developmental assets for adolescents (ages 12–18). Available at: http://www.search-institute.org/system/files/40AssetsList.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monasterio EB. Enhancing resilience in the adolescent. Nurs Clin North Am. 2002;37(3):373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green M, Palfrey J. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Arlington, VA: National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Academy of Pediatrics Connected Kids: Safe, Strong, Secure Clinical Guide. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frankowski BL, Leader IC, Duncan PM. Strength-based interviewing. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2009;20(1):22–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reininger B, Evans A, Griffin Set al. Development of a youth survey to measure risk behaviors, attitudes and assets: examining multiple influences. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(4):461–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naar-King S, Suarez M. Motivational Interviewing With Adolescents and Young Adults. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C. Direct and indirect latent-variable parenting outcomes of two universal family-focused preventive interventions: extending a public health-oriented research base. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(2):385–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borowsky IW, Mozayeny S, Stuenkel K, Ireland M. Effects of a primary care–based intervention on violent behavior and injury in children. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):e392–e399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scudder L, Sullivan K, Copeland-Linder N. Adolescent resilience: lessons for primary care. J Nurse Pract. 2008;4(7):535–543 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barkin SL, Finch SA, Ip EHet al. Is office-based counseling about media use, timeouts, and firearm storage effective? Results from a cluster-randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):e15–e25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ginsburg KR, Forke CM, Cnann A, Slap GB. Important health provider characteristics: the perspective of urban ninth graders. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23(4):237–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satterlee WG, Eggers RG, Grimes DA. Effective medical education: insights from the Cochrane Library. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2008;63(5):329–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Search Institute ParentFurther. Available at: http://www.parentfurther.com. Accessed October 31, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Academic of Pediatrics Building adolescents’ assets and strengths. Available at: http://www.aap.org/sections/adolescenthealth/strengths.cfm. Accessed October 31, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barkin S, Ip E, Finch S, Martin K, Steffes J, Wasserman R. Clinician practice patterns: linking to community resources for childhood aggression. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2006;45(8):750–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation An innovative prescription for better health: Health Leads reaches beyond medical care to improve health. 2011. Available at: http://rwjf.org/vulnerablepopulations/product.jsp?id=72319. Accessed October 28, 2011 [Google Scholar]