Abstract

Purpose

Facebook continues to grow in popularity among adolescents as well as adolescent researchers. Guidance on conducting this research with appropriate attention to privacy and ethics is scarce. To inform such research efforts, the purpose of this study was to determine older adolescents’ responses after learning that they were participants in a research study that involved identification of participants using Facebook.

Methods

Public Facebook profiles of older adolescents age 18 to 19 years from a large state university were examined. Profile owners were then interviewed. During the interview participants were informed that they were identified by examining publicly available Facebook profiles. Participants were asked to discuss their views on this research method.

Results

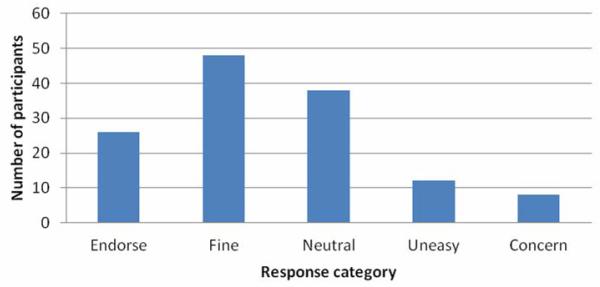

A total of 132 participants completed the interview (70% response rate), the average age was 18.4 years (SD=0.5) and our sample included 64 males (48.5%). Participant responses included: endorsement (19.7%), fine (36.4%), neutral (28.8%), uneasy (9.1%) and concerned (6.1%). Among participants who were uneasy or concerned, the majority voiced confusion regarding their current profile security settings (p=0.00).

Conclusion

The majority of adolescent participants viewed the use of Facebook for research positively. These findings are consistent with the approach taken by many US courts. Researchers may consider these findings when developing research protocols involving Facebook.

Keywords: Adolescent, college student, social networking sites, research ethics, privacy, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Social networking sites (SNSs) are extremely popular, particularly among adolescents and young adults.[1] It is estimated that up to 98% of U.S. college students maintain a SNS profile.[2, 3] Currently, the most popular SNS is Facebook, which recently surpassed Google as the most frequently visited site on the web.[4, 5] Facebook allows profile owners to create an online profile including displayed personal information, to communicate with other profile owners on the SNS and to build an online social network by “friending” profile owners. Profile owners choose among available profile security settings to determine how much of their information to display online. Profile security settings can be “public” (e.g. allowing open access to the profile to any SNS user) or “private” (e.g. limiting some or all profile information access to online friends). “Private” profile security settings can limit access to the entire profile, or settings can be customized to limit access to certain profile viewers or to particular sections of the profile.

Increasingly, SNSs are being used for research to investigate adolescent and young adult behaviors and personality.[6] The nature of SNSs allows large amounts of identifiable information to be revealed and disseminated and thus collected as data.[7] Previous studies have examined adolescents’ health behaviors displayed on SNSs both individually and distributed within online social networks.[8-10] As studies have evaluated publicly displayed information that is often personal, such as substance use or sexual content, concerns have been raised regarding protecting the privacy and confidentiality of research participants.[3, 8, 10, 11] Further, SNSs are now being used for participant recruitment purposes as well as data collection purposes.

Researchers have sought guidance in pursuing this research in a manner consistent with ethical and legal principles. Ethical and legal concerns regarding collection of data from social networking sites have been explored in a handful of papers and legal cases.[12-15] Courts have ruled that a person should have no reasonable expectation of privacy in writings that are posted on a social networking website and made available to the public.[16] Little is known about views of adolescents themselves who are Facebook research participants. This information could assist researchers in developing research protocols that limit concerns about privacy for adolescent research participants.

Many SNS users state that privacy issues regarding displayed profile content are important to them, yet users still choose to display large amounts of personal information.[17] A previous study evaluated college students’ views regarding privacy and information sharing and found that students perceived that they disclosed more information about themselves on Facebook than in offline life, but that information control and privacy were important to them.[17] In another study users claimed to understand privacy issues yet reportedly displayed large amounts of personal information. Participants explained that privacy risks were ascribed to other SNS users rather than to oneself.[18] Similarly, an Australian study found that Facebook users felt that the risk of a privacy violation to them personally was very low, or were not aware of privacy issues.[19] However, a study evaluating college students’ reactions to updated security settings on Facebook found that the majority of respondents were upset over privacy policy changes because of a perceived loss of privacy control, even though there was no increase in the amount of information that was exposed.[7] Thus, while many SNS users report concerns about privacy issues, not all act on these concerns and some SNS users may not completely understand currently available privacy settings.

As researchers who use SNSs, we have occasionally heard concerns raised by human subjects committees and other researchers regarding privacy issues in conducting research in this setting. Given these privacy concerns, questions about the appropriateness of researchers’ use of Facebook to collect information or contact participants require attention. To date, no study has evaluated participants’ views on these topics. As part of an ongoing study assessing college student alcohol use, the objective of this study was to determine older adolescents’ responses after learning that they were participants in a research study that involved identification of participants using Facebook. Our goal was to illuminate findings for other researchers who may have experienced similar concerns in their own SNS research.

METHODS

This study was conducted between November 1, 2009 and July 1, 2011 and received IRB approval from the University of Wisconsin.

Setting and subjects

This study was conducted using the SNS Facebook (www.Facebook.com). Facebook was selected as it is the most popular SNS among our target population of older adolescents.[3, 4] We investigated publicly available Facebook profiles of freshmen undergraduate students within one large state university Facebook network. To be included in the study, profile owners were required to self-report their age as 18 to 19 years old and provide evidence of Facebook profile activity in the last 30 days. We only analyzed profiles for which we could contact the profile owner to invite them to the interview by calling a phone number listed in the university directory or on the Facebook profile.

Data Collection and Recruitment

We used the Facebook search engine to search for profiles within our selected university’s network among the freshmen undergraduate class. This search yielded 416 profiles, all of which we assessed for eligibility. The majority of profiles were ineligible because their profile owners were incorrectly included in search results as their age was not 18 or 19 years (N=36). Other excluded profiles had no contact information (phone number or email) listed within the university directory or their Facebook profile (N=83), or due to privacy settings (N=102). Of privacy exclusions, 87 profiles were fully private and 15 profiles had set the wall section to private. A total of 188 profiles were eligible for evaluation.

Three trained coders evaluated all profiles. As part of an ongoing college health study, the coders viewed all publicly accessible elements of the Facebook profile and recorded basic demographic information such as age and gender. For profiles that met inclusion criteria, profile owners were called on their phone. After verifying identity, the study was explained and profile owners were invited to participate in an interview about college student health. Respondents who completed the interview were provided a $50 incentive.

Interviews

Interviews were conducted one-on-one with a trained interviewer. After explaining the study and obtaining consent, participants completed several health measures for the ongoing study including assessments of alcohol, substance use and mental health. At the conclusion of the interview participants were asked the following single question: “We identified potential participants for this study by looking at publicly available Facebook profiles of people in the university network. Do you have any thoughts about that?” Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Qualitative analysis was conducted in a two step process. First, three investigators viewed a sample of transcripts to characterize the interview responses (AG, LK, MM). We used an iterative process in which transcripts were initially evaluated by each of these three investigators. Then investigators met to review and reach consensus regarding types of interview responses and on other themes present in the data. At the conclusion of this discussion it was determined that responses could be categorized into a 5-point Likert scale. Consensus was reached that the scale would include a rating of 1 represented “strongly dislike” of the method, such as concern or anger on the part of the respondent. A score of 2 represented “somewhat dislike,” an expression of uneasiness with the method. A score of 3 represented neutral or “don’t know” responses. A score of 4 represented a “somewhat like” of the methods, described as “ok” or “fine”. A score of 5 represented “strongly like” the method, such as an endorsement of the method for future studies. A second theme noted was that several participants discussed confusion about their own profile security settings.

In the second stage of analysis, this Likert rating scale was applied to the full dataset by two investigators (AG, LK). These investigators then evaluated each transcript, and provided a supporting quote for the rating. Coders were further asked to document whether statements expressing concerns about profile privacysecurity were discussed. Dissention between ratings was resolved by a third investigator (MM). Interrater agreement was 93%.

Quantitative analysis included descriptive statistics from the Likert scale; logistic regression was used for predictive modeling.

RESULTS

Subjects

A total of 132 participants completed the interview (70% response rate), the average age was 18.4 years (SD 0.49), our sample included 64 males (48.5%) and most participants were White (91.7%). [Table 1] Overall, participant responses regarding their experience and views regarding being a Facebook research participant were distributed across all categories, with most in the neutral or “fine” category.[Figure 1] There were no gender differences in the distribution of response categories.

Table 1.

Demographic information

| n=132 | N (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18.4 (0.4) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 64 (48.8) | |

| Female | 68 (51.2) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 120 (91.7) | |

| Asian | 5 (3.8) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (3.1) | |

|

African

American |

1 (0.7) | |

| Mixed race | 1 (0.7) |

Figure 1.

Participant responses to learning they were a Facebook reasearch participant

Strongly like or Endorse

A total of 26 participant responses (19.7%) fit the category of “strongly like” regarding the use of Facebook as a research method. Participant comments in this category included statements that the method was an appropriate or innovative way to use Facebook, or endorsed the use of Facebook for research purposes. Examples of individual participants’ responses within this category included:

“It’s a good way to look at people’s behavior. A lot of people will post status updates or something about their drinking, so it’s a good way to find participants. And I don’t think it’s bad that you went and looked at people’s profiles, ‘cause if they have them open, it’s their choice.”

“That’s a good way to do [the study]. Because if people are publicly showing their pictures, then it’s, like, open for anyone to see.”

Somewhat like or “Fine”

Most respondents, 48 of the total (36.4%), expressed being fine with the experience of being a Facebook research participant. Participant responses in this category included comments that they were accepting of the method we had used in this study, but did not specifically mention enthusiasm about the use of Facebook as a research tool overall. Examples of individual participants’ responses within this category included:

“It’s on the internet and it’s there for people to see, so it’s fine with me.”

“Well, I mean Facebook is pretty much open to anyone, so as long as it’s not for a bad intention I think it’s fine.”

Neutral or “I don’t know”

A total of 38 respondents (28.8%) were neutral or had no specific comments about using Facebook for research purposes. Participant responses in this category included participants who stated they had no comment, or “I don’t know.” Participants who gave general comments about their use of or experience with Facebook, but did not answer the question about their thoughts on the recruitment method were also grouped in this category. Examples of individual participants’ responses within this category included:

“I don’t know, I don’t really have anything to say about that.”

“(Shrugs) whatever.”

“Before I came [to college] my Facebook was really private, like you couldn’t even search for me I had to search for you. My mom made a Facebook and couldn’t find me.”

Somewhat dislike or Uneasy

Some respondents, 12 of the total (9.1%), fit the category of being uneasy regarding their experience as a Facebook research participant. Participant responses in this category included comments about being uneasy, or unsure if it was ok. Examples of individual participants’ responses within this category included:

“I do feel like in some ways that could be seen as an invasion of privacy, but then again, anything that’s on Facebook is public, and people know that.”

“That sounds kind of weird. I’m not really sure about that.”

Strongly dislike or Concerned

A few respondents, 8 in total (6.1%), fit the category of overt concern about their role as a participant in a Facebook study. Responses in this category included participants who felt uncomfortable or upset with this method. Examples included:

“It’s a little creepy.”

“It’s a little scary I guess, or a little nerve-wracking.”

Privacy confusion

Overall, 20 participants specifically commented that they did not know that their profiles were public or expressed confusion about whether their profile security settings were public or private. Examples of individual participants’ responses within this category included:

“Yes, so that means my Facebook is public right now? I don’t want that”.

“I guess I’m surprised because I thought it was private.”

“I was identified because I was public? Oh I should probably change that (laughs) just because now that I will be looking for, well not a job yet, but potentially, so that could really affect that.”

All of the participants in the “strongly dislike” category and most of the participants in the “somewhat dislike” category voiced privacy concerns. [Table 2] Thus, participants in either dislike category were more likely to express privacy concerns compared to those who were neutral or positive (OR=108, 95% CI [24.5-475.4]). Examples of these quotes include:

“I guess it’s a little worrying that people could detect that. I guess I didn’t even know that mine was public, honestly.”

“Um, my Facebook shouldn’t be public. This is not good news.”

Table 2.

Association between response category and reported privacy confusion among older adolescent participants

| Response category |

Total number of participants |

Number of participants expressing privacy confusion |

|---|---|---|

| Endorse | 26 | 1 |

| Fine | 48 | 2 |

| Neutral | 38 | 1 |

| Uneasy | 12 | 8 |

| Concern | 8 | 8 |

There were no gender differences noted among participants who voiced privacy confusion.

DISCUSSION

The immense popularity of SNSs and their contributions to research thus far suggest that they will continue to be popular among adolescents as well as adolescent researchers. Previous work has shown that users claimed to understand privacy issues, and that risks to privacy invasion were assumed to be low.[18] Our study extends these findings by presenting participants with a direct personal experience with SNS research to determine their responses. Findings suggest that the majority of older adolescent participants viewed the use of Facebook in a research study positively.

One reason for participants’ positive attitude may be that participants do not perceive personal risks to disclosing large amounts of information. It is thought that a combination of high gratification and a psychological mechanism similar to third-person effect lead to an overall relaxed attitude towards privacy of information shared on SNSs.[18] An alternative explanation may be an enhanced understanding by today’s older adolescents that Facebook is a public space. Several of our participants’ comments suggested that the burden of public information disclosure lies in the hands of the profile owner. This attitude may be related to experience and comfort with navigating SNS profile security settings. As Facebook was founded in 2004 and opened to the public a year later, it is possible that some of our participants have maintained a Facebook profile since beginning high school and are comfortable with the public nature of the website.[20]

Recent state and federal court cases reflect the general perception that information posted on a SNS should be viewed as widely available. This issue often arises in the course of discovery, a pre-trial phase of litigation when a party seeks disclosure of SNS pages posted by the opposing party. When the opposing party refuses to disclose such pages, courts must assess whether the opposing party has a reasonable expectation of privacy in the pages such that disclosures is unwarranted. A reasonable expectation of privacy is in turn defined as an expectation that society is prepared to recognize as objectively reasonable given the facts of the case.[21]

Courts generally find that profile owners do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their SNS pages, not even in pages they have deleted or marked as private. In Romano v. Steelcase (2010), for example, defendant Steelcase, Inc. sought disclosure of plaintiff Romano’s Facebook and MySpace pages, including private and deleted pages, to rebut Romano’s claims that Steelcase had injured her.[15] The court granted Steelcase access to these pages, finding that Romano had no reasonable expectation of privacy in this information. The court noted that, in general, a person has no reasonable expectation of privacy in information that has been shared with another person online. Further, the court noted that MySpace and Facebook privacy policies plainly warn that privacy settings cannot guarantee users that the information they post will remain private, and that users should recognize that this information may become publicly available, notwithstanding the users’ privacy settings. The court stressed that information sharing is the “very nature and purpose of these social networking sites else they would cease to exist.” Another court similarly concluded that users logically lack a reasonable expectation of privacy in their own MySpace postings, especially when the user intends the posting to be public.[16] The public nature of SNS pages has become a generally accepted principle of law (92 A.L.R. 5th 15, § 4.5). While it is unlikely that college student participants are uniformly versed in the legal implications of posting information on Facebook, findings suggest that profile owners most often do view Facebook as a public repository of information willingly disclosed by profile owners.

It is important to note that some participants expressed concern regarding their participation in a research study using Facebook. However, many of the participants who expressed such concerns also expressed confusion about their current profile security settings. It is possible that these participants’ negative reactions were rooted in concerns regarding their understanding of their profile security settings. SNS users’ perception of risk in information disclosure can be mitigated by their trust in the network provider and availability of control options.[22] Thus, learning that their information was not as private as they thought may have generated negative reactions by lowering trust in the network provider as well as a perceived loss of personal control over privacy. Therefore, it is unclear whether the discomfort expressed by participants was directed towards being identified as a research participant, or being identified by anyone beyond their online “friends.”

Our study findings are limited in that we only examined publicly available profiles on one SNS. Therefore we cannot generalize to the context or validity of profiles that were set to private, or to profiles on other SNSs. Since our study was conducted in the context of an ongoing study evaluating college student health, it is possible that responses to our question may have been more negatively biased. Participants may have reflected on their own alcohol use or mental health, or displayed health references on their SNS profile, and thus felt increased concern about a researcher viewing the SNS profile. Further, this study was conducted at one institution; generalization to other schools or age groups is not warranted. However, our response rates and data suggesting that the vast majority of college student have a SNS profile support our results as representative of this institution.[2, 3]

Despite these limitations our study has important implications. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore participants’ reactions to direct experience with Facebook research methods. There are several ways in which these findings could be used to enhance SNS research methods. First, researchers should consider that most participants reported feeling positive about using Facebook for research. Several participants reported an explicit understanding that Facebook profiles that are public, are indeed publicly available. Our intent is not to disregard the critical need for confidentiality and respect for privacy in both adolescent health care and research.[23-25] However, our findings indicate that publicly available Facebook profiles of older adolescents are viewed as public spaces by both the adolescents themselves as well as the legal system. Given the knowledge gap that currently exists in understanding adolescents’ interactions with social media, a recent report by the Rand Corporation called for additional research such as content analyses to inform both theory and practice.[26] We hope our findings will promote further research in social media towards these shared goals. Because human subjects committees frequently use legal cases to provide guidance in their approach towards protocol reviews, our findings and related court cases may assist researchers who are considering writing protocols for Facebook research.

Second, researchers should acknowledge that not all participants were positive about their experience with SNS research. Therefore we should continue to enhance our approaches using SNSs for research towards improving participants’ understanding of information sharing. To promote a greater understanding of information sharing in a research setting, researchers could consider whether participants would go as far as “friending” a researcher such that Facebook information would become mutually accessible and information sharing would be understood by both parties. Another option is to consider emailing research participants prior to data collection to allow them to “opt out;” however, this may be in contrast to currently understood terms regarding observation of public information. Another consideration is to send a notification email to profile owners after data collection is complete to explain the study and that data will remain confidential. The current study did not specifically discuss these options with participants to determine their views, and further study is needed before such recommendations should be universally adopted.

Third, a current question facing researchers is how SNS information displays may differ based on whether the profile is private or public, particularly regarding personal or stigmatizing information such as substance use. Based on our findings, researchers should consider that some public profiles may belong to profile owners who believe that the profile security is set to private. Thus, it is possible that the information displayed on public profiles is more similar to private profiles than previously suspected.

In conclusion, findings from this study placed in context of previous work from medical, social science and legal perspectives may provide useful strategies for researchers to create sound research protocols. Ongoing research on the ethics of SNS research is needed as technology and culture continues to evolve.[12, 14, 27, 28]

Acknowledgments

The work described was supported by award K12HD055894 from NICHD and by award R03 AA019572 from NIAAA. The authors would like to acknowledge Megan Pumper, Natalie Goniu and Monet McGruder for their assistance with this project.

Abbreviations

- SNS

Social networking site

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: No authors have conflicts of interest to report.

Implications and Contribution: Our findings indicate that the majority of older adolescent participants viewed the use of Facebook in a research study positively. These findings are consistent with current legal approaches and can provide guidance to researchers when considering Facebook research protocols.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, et al. Social Media and Young Adults. Pew Internet and American Life Project; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis K, Kaufman J, Christakis N. The Taste for Privacy: An Analysis of College Student Privacy Settings in an Online Social Network. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2008 Dec;14(1):79. + [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buffardi LE, Campbell WK. Narcissism and social networking Web sites. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2008 Oct;34(10):1303–1314. doi: 10.1177/0146167208320061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Google [cited 2010 April 16];Google Ad Planner. 2010 Available from: https://www.google.com/adplanner/planning/site_details#siteDetails?identifier=facebook.com&geo=U S&trait_type=1&lp=false.

- 5.Childs M. Facebook surpasses Google in weekly US hits for first time. Business week. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ackland R. Social Network Services as Data Sources and Platforms for e-Researching Social Networks. Social Science Computer Review. 2009 Nov;27(4):481–492. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoadley CM, Xu H, Lee JJ, et al. Privacy as information access and illusory control: The case of the Facebook News Feed privacy outcry. Electron Commer Res Appl. Jan-Feb;9(1):50–60. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Personal information of adolescents on the Internet: A quantitative content analysis of MySpace. J Adolesc. 2008 Feb;31(1):125–146. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moreno MA, Parks M, Richardson LP. What are adolescents showing the world about their health risk behaviors on MySpace? MedGenMed. 2007;9(4):9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreno MA, Parks MR, Zimmerman FJ, et al. Display of health risk behaviors on MySpace by adolescents: Prevalence and Associations. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(1):35–41. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis K, Kaufman J, Gonzalez M, et al. Tastes, ties, and time: A new social network dataset using Facebook.com. Social Networks. 2008 Oct;30(4):330–342. Facebook.com [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno MA, Fost NC, Christakis DA. Research ethics in the MySpace era. Pediatrics. 2008 Jan;121(1):157–161. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmer M. “But the data is already public”: on the ethics of research in Facebook. Ethics and Information Technology. 2010 Dec;12(4):313–325. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flicker S, Haans D, Skinner H. Ethical dilemmas in research on Internet communities. Qual Health Res. 2004 Jan;14(1):124–134. doi: 10.1177/1049732303259842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romano v Steelcase 2010. 30: 30 Misc.3d.

- 16.Moreno v. Hanford Sentinel Inc. 2009. 172 Cal Rptr 3d: Ct App. 2009.

- 17.Christofides E, Muise A, Desmarais S. Information Disclosure and Control on Facebook: Are They Two Sides of the Same Coin or Two Different Processes? Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009 Mar 1; doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Debatin B, Lovejoy JP, Horn AK, et al. Facebook and Online Privacy: Attitudes, Behaviors, and Unintended Consequences. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2009 Oct;15(1):83–108. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tow W, Dell P, Venable J. Understanding information disclosure behavior in Australian Facebook users. Journal of Information Technology. 2010;25(2):126–136. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Facebook [cited 2010 July 19];Facebook information page. 2010 Available from: http://www.facebook.com/facebook?ref=pf#/facebook?v=info&ref=pf.

- 21.Katz v. United States 1967. 389: US.

- 22.Krasnova H, Spiekermann S, Koroleva K, et al. Online social networks: why we disclose. Journal of Information Technology. 2010;25(2):109–125. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spear SJ, English A. Protecting confidentiality to safeguard adolescents’ health: finding common ground. Contraception. 2007 Aug;76(2):73–76. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.English A, Ford CA. More evidence supports the need to protect confidentiality in adolescent health care. J Adolesc Health. 2007 Mar;40(3):199–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santelli JS, Rogers A Smith, Rosenfeld WD, et al. Guidelines for adolescent health research. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2003 Nov;33(5):396–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins RL, Martino S, Shaw R. Influence of New Media on Adolescent Sexual Health: Evidence and Opportunities. RAND Corporation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sixsmith J, Murray CD. Ethical issues in the documentary data analysis of Internet posts and archives. Qual Health Res. 2001 May;11(3):423–432. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Correa T, Hinsley AW, de Zuniga HG. Who interacts on the Web?: The intersection of users’ personality and social media use. Computers in Human Behavior. Mar;26(2):247–253. [Google Scholar]