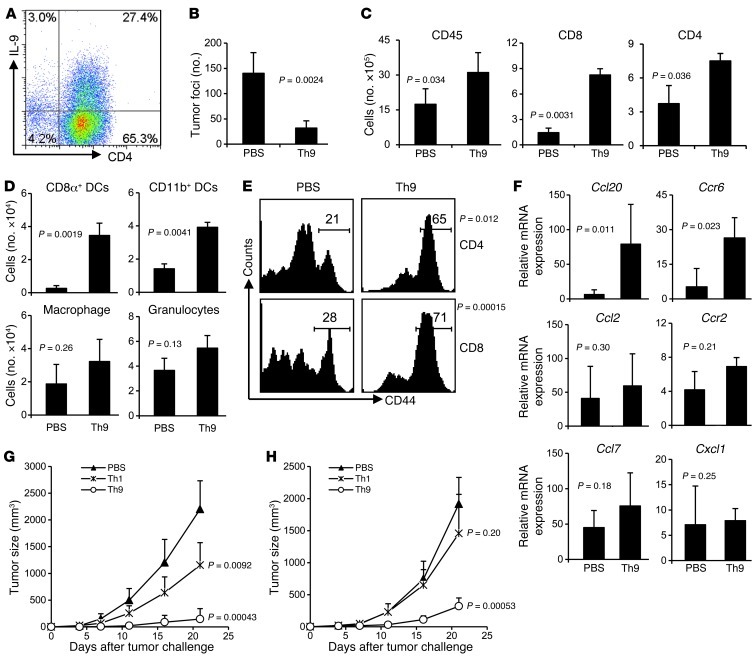

Figure 2. Prophylactic effect of tumor-specific Th9 cells.

(A) OVA-specific Th9 cells used in each experiment typically contained about 25% IL-9–expressing CD4+ OT-II T cells. (B–F) C57BL/6 mice (n = 4–5/group) received PBS or 3 × 106 Τh9 cells on the same day when mice were i.v. challenged with 1 × 105 B16-OVA cells, and were analyzed on day 19 after challenge. (B) Comparison of tumor foci numbers in the lung between PBS- and Th9 cell–treated mice. (C) Number of total leukocytes, CD8+ T cells, and CD4+ T cells in the lung leukocyte fraction analyzed by FACS. (D) Cell numbers of myeloid population subsets in the lung leukocyte fraction analyzed by FACS. (E) Expression of CD44 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from the lung. (F) RT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression of chemokines and their receptors in lung tumor tissues. Data shown were normalized to the β-actin gene. (G) Th1 or Th9 cells (2 × 106) were s.c. injected on the same day and at the same location where 5 × 105 B16-OVA tumor cells had been implanted s.c. Tumor growth curves are shown. P = 0.0033 for Th1 versus Th9 on day 21. (H) Th1 or Th9 cells (3 × 106) were i.v. transferred on the same day that 2 × 105 B16-OVA tumor cells were s.c. injected. Tumor growth curves are shown. P = 0.012 for Th1 versus Th9 on day 21. Representative results from 1 of 3 repeated experiments are shown. The P values in the graphs show comparisons with PBS.