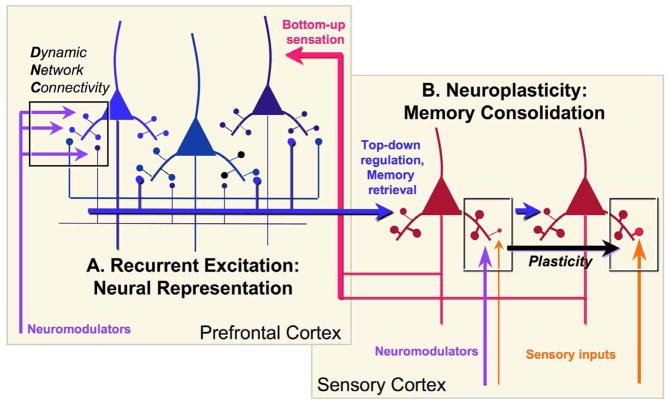

Figure 2.

A highly schematized diagram of the interactions between recurrent, representational circuits in PFC with the sensory association cortices to create the “mental sketch pad”, illustrating the differences between long thin spines in PFC serving the gating processes of DNC, and the thin-type spines that change to mushroom-type to store long-term changes in synaptic efficacy (e.g. traditional neuroplastic changes in sensory cortex and subcortical structures). Neuromodulators shape both processes, but in fundamentally different ways. The sensory cortices provide the PFC with “bottom-up” sensory information, while PFC networks provide “top-down” regulation over the sensory cortex to retrieve stored memories and to guide sensory processing. For example, PFC inputs may enhance the processing of a nonsalient but relevant stimulus (shown), or inhibit the processing of distractors via projections to GABAergic interneurons ((Barbas et al., 2005), not shown). Plasticity occurs in the PFC as well, but is not illustrated for the sake of clarity. Inspired by Fuster, 1997 (Fuster, 1997).