Abstract

Objectives. We describe the prevalence of abuse before, during, and after pregnancy among a national population-based sample of Canadian new mothers.

Methods. We estimated prevalence, frequency, and timing of physical and sexual abuse, identified category of perpetrator, and examined the distribution of abuse by social and demographic characteristics in a weighted sample of 76 500 (unweighted sample = 6421) Canadian mothers interviewed postpartum for the Maternity Experiences Survey (2006–2007).

Results. Prevalence of any abuse in the 2 years before the interviews was 10.9% (6% before pregnancy only, 1.4% during pregnancy only, 1% postpartum only, and 2.5% in any combination of these times). The prevalence of any abuse was higher among low-income mothers (21.2%), lone mothers (35.3%), and Aboriginal mothers (30.6%). In 52% of the cases, abuse was perpetrated by an intimate partner. Receiving information on what to do was reported by 61% of the abused mothers.

Conclusions. Large population-based studies on abuse around pregnancy can facilitate the identification of patterns of abuse and women at high risk for abuse. Before and after pregnancy may be particularly important times to monitor risk of abuse.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines violence against women as

any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.1

This definition is based on the United Nations Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women,2 which affirms that “violence against women constitutes a violation of the rights and fundamental freedoms of women and impairs or nullifies their enjoyment of those rights and freedoms.”2(p1)

Despite the fact that many countries signed this declaration, violence against women still persists in many developed and developing nations.1 It is a global public health concern as it puts many women at severe risk for their health and lives.3,4 Among women of reproductive age, violence has been associated with a range of adverse health and pregnancy problems and outcomes such as unwanted pregnancy,5,6 maternal pregnancy complications,7,8 lower birth weight and preterm birth,9–11 perinatal morbidity,12 maternal physical health problems,13 abortions,14 higher utilization of health care services,15 postpartum depression,16 substance abuse,17 and suicide.18 Socially vulnerable women with low income and low education, unmarried or not cohabitating,19 and at younger age,20 are at higher risk for abuse.

Despite 4 decades of research, however, including hundreds of studies on violence against women in North America, sound estimates of the prevalence of abuse and violence toward women during the childbearing period are difficult to obtain. A recent systematic review of research on violence against pregnant women reported that prevalence varied widely across studies, from a low of 0.9% to a high of 21%.21 In Canada, population-based studies showed that physical violence during pregnancy was 6.6% in Ontario,22 5.7% in Saskatoon,23 and 1.2% in Vancouver.24 Such wide-ranging estimates are not useful to policymakers and program planners designing services to address this critical public health problem.

Prevalence variability across studies is due in part to a variety of factors related to study design. Antenatal clinic-based samples, which are the norm for this type of research,17,25–31 may not be representative of the general population, leading to variations in estimates if, for example, women are predominantly from urban clinic samples or low-income patient populations.19,24,32,33 Response rates vary widely across studies, from a low of 17%27 to a high of 97%30; samples with lower response rates may overrepresent low-risk women.

Modes of inquiry used to assess abuse also vary widely, making comparison across studies a challenge. Although use of face-to-face interviews is common in studies from developing countries, and phone interviews and mailed surveys are often used in developed counties,34 community-based surveys33 and self-administered assessments have also been employed.30 Studies have shown that women have different levels of comfort in disclosing abuse depending on the mode of inquiry, with phone and self-administered methods facilitating disclosure.35–37 Assessment tools also vary in their coverage of behaviors that constitute partner violence.37–40 Thus, myriad study design features have influenced the population prevalence rates reported in studies and their generalizability.

In summary, few studies on abuse during pregnancy employ large population-based samples of women that enable a presentation of prevalence by subgroups and include rich information about the type, timing, frequency, and severity of abuse and the perpetrators involved. We build on the existing literature on abuse and perpetration patterns using a Canadian national sample of new mothers who were asked about abuse prior to and during pregnancy, as well as in the first several months postpartum.

Our objectives were to estimate the prevalence, frequency, timing, and types of physical abuse before, during, and after pregnancy; to identify the category of perpetrator; and to examine the onset and cessation of abuse around pregnancy among a national representative sample of mothers who participated in the Maternity Experiences Survey (MES).

METHODS

The MES was conducted by the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System, Public Health Agency of Canada, to enable descriptions of women's experiences before and during pregnancy and after giving birth; details about the design and methods of the MES are provided in detail elsewhere.41,42 The survey collected information from a stratified random sample of mothers in Canadian provinces and territories, using recent births drawn from the 2006 Canadian Census of Population. Data were collected from October 2006 through January 2007 in a 45-minute telephone interview by trained female Statistics Canada interviewers in English, French, or 1 of 13 nonofficial languages. Women were eligible to participate if they were aged 15 years or older, had given birth to a singleton live infant in Canada, and were living with the infant at the time of the interview. The interviews took place between 5 and 14 months postpartum; 97% of the interviews occurred between 5 and 9 months postpartum. The final sample size was 6421 and the response rate was 78%.

In Canada, historical experiences have guided the emergence of new ethical principles and policies that enable Aboriginal groups to participate in the development of knowledge to benefit their communities.43,44 A key policy is community–researcher engagement around all research activities and the reporting of data on Aboriginal populations. In keeping with this policy, we involved the Native Women’s Association of Canada in the final drafting of this article to ensure that the Aboriginal-specific analysis benefited from their expertise, and we received their endorsement to present the results.

Study Variables

Women were asked the following yes-or-no questions on abuse that were adapted from the Canadian Violence Against Women Survey45: In the last 2 years, has anyone ever

Threatened to hit you with his or her fist or anything else that could have hurt you?

Thrown anything at you that could have hurt you?

Pushed, grabbed, or shoved you in a way that could have hurt you?

Slapped you?

Kicked you, bit you, or hit you with his or her fist?

Hit you with something that could have hurt you? Exclude hitting with a fist.

Beaten you?

Choked you?

Used or threatened to use a gun or knife on you?

Forced you into any unwanted sexual activity by threatening you, holding you down, or hurting you in some way?

Women who answered yes to any of the previous categories of abuse were asked about their relationship to the perpetrator—whether he was (1) her partner, husband, or boyfriend, (2) a family member, (3) a friend or acquaintance, (4) a stranger, or (5) other. If a woman answered the first option, it was considered intimate partner violence.

Women were then asked about the frequency of events and, finally, they were asked about whether these abusive acts happened before, during, or after pregnancy. Abused women were asked if, during the last 2 years, they had discussed or received information about what to do if they were experiencing abuse.

The survey collected socioeconomic information on education (less than high school, high school only, postsecondary below bachelor degree, and bachelor degree or higher) and household income (<Can $20 000, $20 000–$49 999, $50 000–$79 999, and ≥ $80 000), which was used to determine whether women lived above or below the low-income cutoff (LICO). The LICO reflects whether the respondent lived in a household spending 20 percentage points more of their after-tax income on food, shelter, and clothing than the average family, thus leaving less income available for other expenses such as health, education, transportation, and recreation. The LICOs are set here at after-tax income levels, differentiated by size of family and area of residence.46

Demographic information included the following: maternal age, marital status (because of small numbers, we combined single, divorced, separated, and widowed into 1 category called “lone mothers” vs married or cohabitating), ethnicity and immigration (Canadian-born non-Aboriginal, Aboriginal, and foreign-born immigrant), and urban vs rural residence. The MES excluded Aboriginal women living on reserve.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated the prevalence of any abuse (reporting ≥ 1 of the 10 items) and other abuse-related variables for the weighted sample of mothers. The weights were provided by Statistics Canada to account for the complex sampling design. We weighted and calculated percentages (with 95% confidence intervals) by the jackknife method of variance estimation.47 The level of sampling error affecting estimates was based on the coefficient of variation, with coefficients below 16.6% being of good quality, those in the range 16.7% to 33.2% of marginal quality, and those 33.3% and higher considered unreliable.42 We performed data analysis using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).42 The MES guidelines recommend reporting of weighted counts rounded to the nearest 100 and forbid presenting estimates based on cell counts of less than 5.42 Missing data were not considered in the analysis as they were very infrequent in the outcome and stratifying variables (i.e., in the range 0.4%–1.0%), with the only exception being low income (9.0%), for which we created a category labeled “missing” to prevent a significant drop in the sample size. We compared proportions using the Rao-Scott χ2 test, which adjusts for design effects.42

After examining the distribution of demographics and socioeconomic variables for the total sample of participants and for women who reported any abuse, we estimated the prevalence of individual types of abuse, as well as abuse frequency (1, 2–5, or ≥ 6 times), perpetrator (partner, family member, friend, stranger, or other), and timing of abuse (before, during, or after pregnancy or at all times) for the total sample of participants and for 2 strata of at-risk groups19 from the total sample (i.e., lone mothers and mothers below the LICO). Finally, we examined patterns of abuse in 6 nonmutually exclusive periods:

before pregnancy only,

during pregnancy only,

after pregnancy only,

before and after pregnancy,

before and during pregnancy, and

during and after pregnancy.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the total weighted sample of 76 500 women are presented in Table 1. Overall, 10.9% of the weighted sample (unweighted n = 791) reported experiencing abuse of any type in the 2 years prior to the interview. The majority of women giving birth were aged between 25 and 34 years, with far fewer aged 15 to 19 years or 40 years and older. Most women had educational levels higher than a high school diploma, with more than a third having a university degree or higher. Most women lived in households above the LICO. About 24% were foreign-born, and 4.2% were Aboriginal. Most women were married or cohabitating and resided in urban areas.

TABLE 1—

Distribution of the Full Weighted Sample of Participants by Sociodemographic Characteristics and Prevalence of Abuse: Maternity Experiences Survey, Canada, 2006–2007

| Characteristics | Distribution of Participants, % (95% CI) | Prevalence of Abuse, % (95% CI) | P |

| Abuse | |||

| Any in past 2 y | 10.9 (10.1, 11.8) | ||

| None | 89.1 (88.3, 9.9) | ||

| Age, y | < .001 | ||

| 15–19 | 3.1 (2.6, 3.3)a | 40.7 (34.4, 46.9) | |

| 20–24 | 13.1 (12.2, 14.0) | 21.6 (18.6, 24.6) | |

| 25–29 | 33.2 (32.0, 34.5) | 9.5 (8.2, 10.9) | |

| 30–34 | 33.1 (31.8, 34.3) | 7.9 (6.7, 9.2) | |

| 35–39 | 14.6 (13.6, 15.5) | 6.1 (4.4, 7.7) | |

| 40–55 | 2.9 (2.5, 3.4) | 7.6 (3.5, 11.6)a | |

| Education | < .001 | ||

| < high school | 7.7 (7.0, 8.3) | 24.1 (20.2, 28.0) | |

| High school only | 19.4 (18.3, 20.4) | 16.2 (14.1, 18.4) | |

| Any postsecondary below bachelor degree | 37.4 (36.1, 38.7) | 10.0 (8.7, 11.3) | |

| Bachelor degree or higher graduate degree | 35.5 (34.2, 36.8) | 6.3 (5.2, 7.4) | |

| Total household income, Can $ | < .001 | ||

| < 20 000 | 9.3 (8.5, 10.1) | 27.8 (23.9, 31.7) | |

| 20 000–49 999 | 28.1 (26.8, 29.3) | 12.3 (10.6, 13.9) | |

| 50 000–79 999 | 29.2 (28.0, 30.5) | 8.7 (7.3, 10.1) | |

| ≥ 80 000 | 33.4 (32.1, 34.7) | 6.7 (5.5, 7.9) | |

| LICO | < .001 | ||

| ≤ LICO | 18.4 (17.4, 19.4) | 21.1 (18.6, 23.5) | |

| > LICO | 72.6 (71.4 73.8) | 8.3 (7.5, 9.2) | |

| Missing | 9.0 (8.2, 9.8) | 11.5 (8.8, 14.1) | |

| Ethnicity and migration | < .001 | ||

| Canadian-born non-Aboriginal | 72.0 (70.7, 73.2) | 11.7 (10.7, 12.7) | |

| Aboriginal | 4.2 (3.7, 4.7) | 30.6 (25.2, 35.9) | |

| Foreign-born | 23.8 (21.0, 25.6) | 5.5 (4.2, 6.8) | |

| Marital status | < .001 | ||

| Loneb | 8.4 (7.7, 9.1) | 35.3 (31.2, 39.5) | |

| Married or cohabitating | 91.6 (90.9, 92.3) | 8.7 (8.0, 9.5) | |

| Geographic area | .399 | ||

| Urban | 83.1 (82.1, 84.1) | 10.9 (10.0, 11.8) | |

| Rural | 16.9 (15.9, 17.9) | 11.8 (9.8, 13.7) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; LICO = low-income cuttoff. The LICO reflects whether the respondent lived in a household spending 20 percentage points more of their after-tax income on food, shelter, and clothing than the average family, thus leaving less income available for other expenses such as health, education, transportation, and recreation. The LICOs are set here at after-tax income levels, differentiated by size of family and area of residence.46 The full weighted sample size was n = 76 500.

Coefficient of variation is between 16.6% and 33.3%, indicating marginal quality of the estimates; some caution is required in interpreting these results.

Lone mothers include those single, divorced, separated, or widowed.

The prevalence of any abuse varied according to sociodemographic characteristics (Table 1, second column). Frequency of abuse was highest among adolescents (40.7%) and decreased with increasing maternal age (P < .001) and higher educational attainment and household income (P < .001). Women living in a household below the LICO reported more abuse (21.1%) than did women who lived above the LICO (8.3%) (P < .001). Abuse also varied according to ethnicity and immigration (P < .001), with Aboriginal women reporting the highest frequency (30.6%) and immigrant women the lowest (5.5%). Lone mothers reported very high rates of abuse (35.3%; P < .001). We observed no significant difference between women living in urban and rural areas (P = .399).

Table 2 shows the prevalence of abuse characteristics in the full sample, among women living in low-income households, and among lone mothers. In the 3 groups, the most prevalent item of abuse was being pushed, grabbed, or shoved. Most of the mothers in the full sample experienced abuse 1 time, whereas mothers below the LICO and lone mothers reported recurrent abuse (2–5 times). The partner was the most prevalent perpetrator of abuse. Mothers were mostly exposed to abuse before pregnancy. In the full sample, 6% reported abuse before pregnancy only, 1.4% during pregnancy only, and 1% postpartum only, whereas 2.5% reported abuse at some combination of these times (Table 2).

TABLE 2—

Prevalence of Abuse for the Full Weighted Sample, for Mothers Below the Low-Income Cutoff (LICO), and for Lone Mothers: Maternity Experiences Survey, Canada, 2006–2007

| Variables | Full Sample (Weighted n = 76 500), % (95% CI) | Mothers Below LICO (Weighted n = 14 100), % (95% CI) | Lonea Mothers (Weighted n = 6400), % (95% CI) |

| Abuse | |||

| Any in past 2 y | 10.9 (10.1, 11.8) | 21.1 (18.6, 23.5) | 35.3 (31.2, 39.5) |

| None | 89.1 (88.3, 89.9) | 78.9 (76.5, 81.4) | 64.7 (60.5, 68.8) |

| Abuse items | |||

| Threatened to hit | 5.4 (4.8, 6.0) | 12.2 (10.3, 14.2) | 23.4 (19.7, 27.1) |

| Threw something | 4.5 (4.0, 5.0) | 9.9 (8.1, 11.7) | 16.9 (13.6, 20.2) |

| Pushed, grabbed, shoved | 7.0 (6.3, 7.7) | 15.6 (13.4, 7.8) | 27.6 (23.7, 31.5) |

| Slapped | 2.6 (2.2, 3.0) | 6.9 (5.4, 8.4) | 12.4 (9.6, 15.3) |

| Kicked | 3.4 (2.9, 3.8) | 7.1 (5.6, 8.6) | 13.9 (11.0, 16.9) |

| Hit | 1.9 (1.5, 2.2) | 4.5 (3.3, 5.7) | 7.6 (5.4, 9.8) |

| Beat | 0.8 (0.5, 1.0) | 3.0 (2.0, 4.0)b | 5.1 (3.2, 7.0)b |

| Choked | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) | 3.5 (2.4, 4.6) | 7.4 (5.1, 9.7) |

| Used or threatened gun or knife | 0.9 (0.6, 1.1) | 2.7 (1.7, 3.6)b | 5.0 (3.1, 6.9)b |

| Forced sex | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9) | 2.3 (1.4, 3.2)b | 3.2 (1.8, 4.7)b |

| Abuse frequency | |||

| 1 time | 4.6 (4.1, 5.2) | 7.2 (5.7, 8.7) | 9.0 (6.6, 11.3) |

| 2–5 times | 4.0 (3.5, 4.5) | 8.5 (6.8, 10.2) | 14.7 (11.6, 17.8) |

| ≥ 6 times | 2.1 (1.7, 2.4) | 4.8 (3.5, 6.1) | 10.6 (7.9, 13.3) |

| Abuse perpetrator | |||

| Partner | 5.7 (5.1, 6.3) | 12.0 (10.0, 13.9) | 23.3 (19.6, 27.0) |

| Family member | 1.8 (1.5, 2.1) | 3.3 (2.3, 4.4) | 4.4 (2.7, 6.1)b |

| Friend or acquaintance | 1.4 (1.1, 1.7) | 3.8 (2.7, 5.0) | 5.7 (3.6, 7.7)b |

| Stranger or other | 2.3 (1.9, 2.7) | 3.0 (2.0, 4.1)b | 3.9 (2.2, 5.6)b |

| Abuse timing | |||

| Before pregnancy only | 6.0 (5.3, 6.6) | 12.0 (10.0, 14.0) | 18.4 (15.0, 21.7) |

| During pregnancy only | 1.4 (1.1, 1.7) | 2.0 (1.1, 2.8)b | 3.7 (2.2, 5.3)b |

| After birth only | 1.0 (0.7, 1.2) | 1.7 (0.9, 2.4)b | 2.0 (0.8, 3.1)b |

| Before and during pregnancy | 1.2 (0.9, 1.4) | 2.4 (1.5, 3.3)b | 4.8 (2.8, 6.7)b |

| Before pregnancy and after birth | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7)b | 1.3 (0.6, 1.9)b | 2.9 (1.4, 4.4)b |

| During pregnancy and after birth | 0.2 (0.1, 0.3)b | 0.4 (0.1, 0.8)c | 1.2 (0.2, 2.2) |

| At all 3 times | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7)b | 0.9 (0.4, 1.5)b | 1.8 (0.7, 2.8)b |

Note. CI = confidence interval. The LICO reflects whether the respondent lived in a household spending 20 percentage points more of their after-tax income on food, shelter, and clothing than the average family, thus leaving less income available for other expenses such as health, education, transportation, and recreation. The LICOs are set here at after-tax income levels, differentiated by size of family and area of residence.46

Lone mothers include those single, divorced, separated, or widowed.

Coefficient of variation is between 16.6% and 33.3%, indicating marginal quality of the estimates; caution is required in interpreting these results.

Coefficient of variation is above 33.3%, indicating poor quality of the estimates. Extreme caution is required in interpreting these results.

Table 3, which focuses only on abused women, presents the frequency of abuse-related characteristics in the full sample of abused women and among mothers living below the LICO and lone mothers. The most frequent types of abuse were threats to hit; throwing something; pushing, grabbing, or shoving; slapping; kicking; hitting; beating; and choking. All of these types of abuse were particularly high among lone mothers. Proportionately fewer lone and below-LICO mothers experienced abuse only 1 time, whereas both groups, especially lone mothers, reported recurrence of abuse. More than half of abused women were abused before pregnancy but not after. Only about 5% of abused women were repeatedly abused before, during, and after pregnancy. A similar proportion of abused mothers (about 61%) in each group received information about what to do when experiencing abuse.

TABLE 3—

Prevalence of Abuse for the Full Sample of Abused Mothers, for Abused Mothers Below the Low-Income Cutoff (LICO), and for Abused Lone Mothers: Maternity Experiences Survey, Canada, 2006–2007

| Variables | Full Sample of Abused Women (Weighted n = 8400), % (95% CI) | Abuse Among Mothers Below LICO (Weighted n = 3000), % (95% CI) | Abuse Among Lonea Mothers (Weighted n = 2300), % (95% CI) |

| Abuse itemsb | |||

| Threatened to hit | 49.2 (45.3, 53.1) | 58.1 (51.6, 64.6) | 66.2 (59.3, 73.1) |

| Threw something | 41.2 (37.3, 45.0) | 47.1 (40.6, 53.6) | 47.9 (40.6, 55.2) |

| Pushed, grabbed, shoved | 63.9 (60.2, 67.7) | 74.1 (69.3, 79.8) | 78.2 (72.2, 84.1) |

| Slapped | 23.4 (20.1, 26.6) | 32.6 (26.5, 38.7) | 35.2 (28.3, 42.2) |

| Kicked | 30.8 (27.3, 34.4) | 33.8 (27.7, 39.9) | 39.5 (32.4, 46.6) |

| Hit | 17.3 (14.4, 20.3) | 21.2 (15.9, 26.4) | 21.5 (15.6, 27.4) |

| Beat | 7.0 (5.1, 8.9) | 14.1 (9.6, 18.7) | 14.5 (9.4, 19.6)c |

| Choked | 10.4 (8.0, 12.7) | 16.8 (11.9, 21.7) | 20.9 (14.9, 26.9) |

| Used or threatened gun or knife | 7.9 (5.8, 10.0) | 12.6 (8.2, 17.1)c | 14.2 (9.1, 19.4)c |

| Forced sex | 6.0 (4.2, 7.8) | 10.9 (6.9, 14.8)c | 9.2 (5.1, 13.2)c |

| Abuse frequency | |||

| 1 time | 43.4 (39.4, 47.3) | 35.1 (28.8, 41.4) | 26.2 (19.9, 32.5) |

| 2–5 times | 37.3 (33.5, 41.2) | 41.5 (35.0, 48.0) | 43.0 (35.6, 50.3) |

| ≥ 6 times | 19.3 (16.2, 22.4) | 23.4 (17.8, 29.0) | 30.8 (24.0, 37.7) |

| Abuse perpetrator | |||

| Partner | 52.0 (48.1, 55.9) | 57.1 (5.7, 63.8) | 66.9 (60.1, 73.7) |

| Family member | 16.5 (13.6, 19.3) | 15.9 (11.4, 20.5) | 12.7 (8.0, 17.4)c |

| Friend or acquaintance | 13.0 (10.4, 15.6) | 18.4 (13.4, 23.3) | 16.2 (10.8, 21.7)c |

| Stranger or other | 21.3 (18.1, 24.5) | 14.4 (9.8, 19.1) | 11.0 (6.5, 15.6)c |

| Abuse timingb | |||

| Before pregnancy only | 55.7 (51.8, 59.6) | 58.2 (51.8, 64.7) | 52.9 (45.6, 60.2) |

| During pregnancy only | 13.0 (10.3, 15.7) | 9.5 (5.7, 13.3)c | 10.8 (6.4, 15.2)c |

| After birth only | 9.0 (6.8, 11.2) | 8.0 (4.5, 11.6)c | 5.7 (2.5, 9.0)c |

| Before and during pregnancy | 10.9 (8.5, 13.4) | 11.5 (7.3, 15.8)c | 13.8 (8.5, 19.1)c |

| Before pregnancy and after birth | 4.9 (3.3, 6.6)c | 6.1 (3.0, 9.3)c | 8.4 (4.2, 12.5)c |

| During pregnancy and after birth | 1.7 (0.6, 2.7)c | 2.0 (0.2, 3.8)d | 3.4 (0.6, 6.2)d |

| At all 3 times | 4.8 (3.2, 6.4) | 4.6 (2.1, 7.2)c | 5.1 (2.1, 8.1)c |

| Discussed abuse or received information about abuse | |||

| Yes | 61.0 (57.2, 64.8) | 63.7 (57.4, 69.9) | 60.8 (53.6, 67.9) |

| No | 39.0 (35.2, 42.8) | 36.3 (30.1, 42.6) | 39.2 (32.1, 46.4) |

Note. CI = confidence interval. Missing values are not considered in the calculations. Weighted n values differing from those shown in column heads are as follows: for abuse frequency, n = 8200 for full sample and n = 2200 for lone mothers; for abuse perpetrator, n = 8300 for full sample and n = 2200 for lone mothers; for abuse timing, n = 8200 for full sample, n = 2900 for mothers below LICO, and n = 2200 for lone mothers. The LICO reflects whether the respondent lived in a household spending 20 percentage points more of their after-tax income on food, shelter, and clothing than the average family, thus leaving less income available for other expenses such as health, education, transportation, and recreation. The LICOs are set here at after-tax income levels, differentiated by size of family and area of residence.46

Lone mothers include those single, divorced, separated, or widowed.

Categories overlap and therefore do not add up to 100%.

Coefficient of variation is between 16.6% and 33.3%, indicating marginal quality of the estimates; caution is required in interpreting these results.

Coefficient of variation is above 33.3%, indicating poor quality of the estimates; extreme caution is required in interpreting these results.

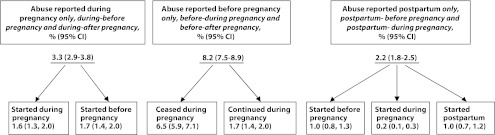

The onset and cessation of any abuse around pregnancy are shown in Figure 1. Among mothers who experienced abuse during pregnancy (exclusively or in combination with other times; 3.3%), about 50% reported that abuse started during pregnancy; for the other half, abuse started before pregnancy. For most mothers who reported abuse before pregnancy, abuse did not continue during pregnancy. For mothers who reported postpartum abuse, the same proportion (1%) reported that the onset of abuse was before pregnancy or postpartum.

FIGURE 1—

Timing of abuse, and of onset and cessation of abuse, around the time of pregnancy among childbearing mothers: Maternity Experiences Survey, Canada, 2006–2007.

Note. CI = confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

We report here on one of the few nationwide population-based studies to examine the magnitude of abuse against childbearing women.19,33 We found the prevalence of physical or sexual violence in the 2 years prior to the interview to be 10.9%, higher than the findings of previous 2 population-based studies that reported physical abuse: 8.7% in the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Study in 16 states in the United States (which includes all times before, during, and after pregnancy)19 and 8.5% in a study in 32 provinces of China.33 However, caution is recommended when comparing these results, as the exposure time in the current study was 2 years whereas in the other studies measured abuse during 1 year prior to the interview.19,33 Generally, it is difficult to compare our findings with most previous results because studies of abuse around the time of pregnancy were mostly clinic based or conducted in shelters for battered women21 and few included a representative sample of the population.19,33 Furthermore, some studies used broader measures of abuse (e.g., emotional, physical, or sexual) or examined only intimate partner violence.32

Similar to those of previous studies,26,48–51 our results indicated that the prevalence of abuse is high among young, lone, and low-income mothers. The prevalence of abuse was 40.7% among younger mothers (< 20 years), compared with less than 10% among mothers aged 25 years or older. This was similar to findings by Saltzman et al., using a population-based study, that during pregnancy women younger than 20 years were 4.3 times more likely to experience abuse than were women aged 30 years or older.19

Lone marital status was an important risk factor. Lone mothers had high rates and frequencies of all abuse types and more intimate partner violence. Some previous studies showed that after controlling for a number of confounders, lone pregnant women were 3 to 4 times more likely to experience abuse than married or cohabitating mothers,19,32,51 but others showed that the differences between married and unmarried women disappeared after controlling for different variables.23,52 These inconsistent findings need to be explored more in future research.

Mothers with less than a high school education had an abuse rate of 24.1%, which is 4 times higher than for university-educated mothers. This was consistent with the PRAMS Study, in which women with less than 12 years of education had 4.7 times more abuse than women with more than 12 years of education.19 Similarly, the prevalence of abuse was higher among women living in low-income (< $20 000) and below-LICO households, a finding that is consistent with previous studies in Canada23,51 and New Zealand.53 We did not find differences in abuse among women living in urban compared with rural areas.

Consistent with previous findings,24,51 Aboriginal women reported higher rates of abuse than Canadian-born non-Aboriginal women. This has been linked to multigenerational colonial trauma and the forced imposition of Euro-Western systems of patriarchy.54,55

In our study, immigrant women reported the lowest rates of abuse compared with the other subgroups. Other studies have reported conflicting results on abuse against immigrant women.21 Researchers suggest that a low proportion of abuse reflects underreporting among immigrant women56 because of cultural attributes and financial dependency on the husband.57,58 Universal tools might fail to capture violence against immigrant women in specific cultural groups. Validation of tools across cultural and language groups is recommended. Others suggested that the length of stay in Canada might affect the magnitude of abuse among immigrant women.59 In a preliminary analysis for this report, we found that whereas immigrants as a whole had lower prevalence of abuse than their Canadian-born counterparts, 4.9% of recent immigrants (< 10 years of stay) experienced abuse compared with 6.3% among long-term immigrants (≥ 10 years), although the difference was not statistically significant (P = .206). Immigrants are a diverse group (culturally and by country of origin, etc.); future research should try to better differentiate this group.

Regarding timing of abuse, we found a prevalence of 6% before pregnancy only, 1.4% during pregnancy only, and 1% after pregnancy only. Our results on abuse before pregnancy only were lower than the 7.2% found in the PRAMS Study in the United States19 but higher than the 3.3% found in the Chinese study.33 These differences could be related to different measures of physical abuse but also to whether the studies reported exclusive abuse for each period (before only, during only, and after only) or overlapping abuse timing (before and during pregnancy, before and after pregnancy, and during and after pregnancy). Both the PRAMS and Chinese studies reported abuse during 12 months before pregnancy, whereas the MES did not specifically define the time of abuse before pregnancy. The MES asked about abuse that occurred during the 2 years prior to the interview, so timing of abuse before pregnancy would vary on the basis of gestational age at birth and postpartum timing of the interview.

The lower rates of abuse during pregnancy are consistent with previous evidence suggesting that pregnancy could be a period when violence against women is reduced compared with the prepregnancy and postpartum periods.20,60 These findings have implications for screening. Screening should take place before, during, and after pregnancy19,48,61 and not be limited to current experiences given the risk of recurrence.19,37,53,62,63

Our results were inconsistent with those of a previous study reporting that abuse was more common postpartum than during pregnancy.60 We found lower postpartum abuse (2.2%) than in the North Carolina PRAMS Study (3.2%),48 the Chinese study (7.4%),33 and a clinic-based study,60 suggesting that in addition to pregnancy, birth might be protective for women at reproductive age in Canada.

Onset and cessation of abuse were consistent with previous results, suggesting that pregnant women experience abuse less frequently.48 The patterns we report may be specific to physical and sexual abuse. Martin et al.64 suggested that the form of abuse might change during pregnancy. Emotional abuse may increase during pregnancy, when physical abuse is reduced.32

Recurrent abuse is an important indicator of severity of abuse.65 In the current study, 43.4% of abused women reported only 1 incident, 37.3% reported abuse occurring 2 to 5 times, and 19.3% reported 6 or more episodes. These results were lower than those of a previous study involving low-income women, which found that 60% of the sample were exposed to more than 2 episodes of abuse during pregnancy.66

Although this and other studies show that perpetrators can be individuals other than intimate partners, most abuse is perpetrated by intimate partners.31 Our findings indicated that prevalence of abuse perpetrated by intimate partners was 5.7% in the total sample and 52% among the abused mothers. This was in the range of previous results; the US Department of Justice estimated intimate partner violence to be 4% to 8%.67 A national sample in the United States32 reported rates of physical violence by intimate partners of 9.6% during pregnancy and 3.1% after pregnancy. A review of Canadian studies reported a range of intimate partner violence of 0.4% to 23%.68 In the North Carolina PRAMS Study in the United States, intimate partner violence was between 67% and 76%, varying depending on the timing in relation to the pregnancy.48

The finding that only 61% of abused mothers reported receiving information on what to do when experiencing abuse has important policy implications. This information needs to be more available to victims of violence—especially low-income and lone mothers, who are at higher risk for abuse but whose reported rates of receiving information were almost the same as those for other abused women.

Limitations

Limitations of our analysis include possible underreporting of abuse because of nondisclosure. In addition, a limited set of abuse-related behaviors on the questionnaire may have contributed to underreporting of the true extent of abuse, as we did not ask about emotional abuse or controlling behaviors, which tend to be of higher prevalence than physical or sexual abuse.32,64,69 We had no information about perpetrator characteristics other than their relationship to the victim of abuse. The sample was intended to be nationally representative, which limited opportunities to explore patterns and risks among subgroups experiencing the highest rates of abuse and violence. Caution is needed in generalizing these rates of abuse beyond women having a singleton live birth and living with their infant at 5 to 9 months. Women with multiple births, abuse resulting in a stillbirth or neonatal death, and a poor social situation resulting in apprehension of the infant by welfare agencies were not included in this sample. Exclusion of First Nations women living on reserve was another limitation that might have attenuated rates reported for Aboriginal women.

Conclusions

Our results are consistent with the growing literature on partner violence around the time of pregnancy that uses a large population-based sample. As in previous studies, we also identified lone women and women with low socioeconomic position as being at high risk for abuse. Because our aim was not to conduct comparisons between these groups but to present the prevalence of abuse among them, we suggest that future studies should conduct multivariate analysis to control for potential confounders.

We have extended previous studies by reporting on the specific types of abuse experienced as well as the multiple perpetrators of abuse. In addition, we were able to contribute to this literature by gathering information on patterns of abuse before, during, and after pregnancy, illustrating the relative risk of abuse over these 3 time periods. Our findings suggest that women should be monitored for abuse not only during pregnancy but also before and after pregnancy, as our data suggest that these are periods of higher risk for abuse. Information on what to do if abuse is experienced needs to become more available to all women who are victims of violence.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Maternity Experiences Study Group of the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System, who developed and implemented the Maternity Experiences Survey. We also thank the National Native Women’s Association of Canada, who reviewed the article and confirmed that the results presented accord with the code of ethnics of research on the Aboriginal peoples.

Human Participant Protection

The Maternity Experiences Survey (MES) project was presented to Health Canada’s Science Advisory Board, Health Canada’s Research Ethics Board, and the Federal Privacy Commissioner and was approved by Statistics Canada’s Policy Committee. This secondary analysis of the MES was approved by the St. Michael’s Hospital Research Ethics Board and by the Research Data Centre Access Granting Committee of Statistics Canada. To comply with the Guidelines for Health Research Involving Aboriginal Peoples, we involved an Aboriginal researcher and received the approval of the National Native Women’s Association of Canada.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Violence Against Women, Fact Sheet N°239. Updated September 2011. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs239/en. Accessed July 5, 2012.

- 2.United Nations General Assembly. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women, General Assembly Resolution 48/104, December 20, 1993. Available at: http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/48/a48r104.htm. Accessed March 25, 2011.

- 3.WHO Multi-Country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence Against Women. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watts C, Zimmerman C. Violence against women: global scope and magnitude. Lancet. 2002;359(9313):1232–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pallitto C, Campbell J, O'Campo P. Is intimate partner violence associated with unintended pregnancy? A review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2005;6(3):217–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pallitto C, O'Campo P. The relationship between intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy: analysis of a national sample from Colombia. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2004;30(4):165–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambliss L. Intimate partner violence and its implication for pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51(2):385–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leone J, Lane S, Koumans Eet al. Effects of intimate partner violence on pregnancy trauma and placental abruption. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19(8):1501–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipsky S, Holt V, Easterling T, Critchlow C. Impact of police-reported intimate partner violence during pregnancy on birth outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(3):557–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarkar N. The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. Review J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28(3):266–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altarac M, Strobino D. Abuse during pregnancy and stress because of abuse during pregnancy and birthweight. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2002;57(4):208–214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berenson A, Wiemann C, Wilkinson G, Jones W, Anderson G. Perinatal morbidity associated with violence experienced by pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170(6):1760–1769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ansara D, Cohen M, Gallop R, Kung R, Schei B. Predictors of women's physical health problems after childbirth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;26(2):115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourassa D, Berube J. The prevalence of intimate partner violence among women and teenagers seeking abortion compared with those continuing pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29(5):415–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloom T, Curry M, Durham L. Abuse and psychosocial stress as factors in high utilization of medical services during pregnancy. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2007;28(8):849–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beydoun H, Al-Sahab B, Beydoun M, Tamim H. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for postpartum depression among Canadian women in the Maternity Experience Survey. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(8):575–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curry MA. The interrelationships between abuse, substance use, and psychosocial stress during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1998;27(6):692–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bayatpour M, Wells R, Holford S. Physical and sexual abuse as predictors of substance use and suicide among pregnant teenagers. J Adolesc Health. 1992;13(2):128–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saltzman LE, Johnson CH, Gilbert BC, Goodwin MM. Physical abuse around the time of pregnancy: an examination of prevalence and risk factors in 16 states. Matern Child Health J. 2003;7(1):31–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gazmararian J, Lazorick S, Spitz A, Ballard T, Saltzman L, Marks J. Prevalence of violence against pregnant women. JAMA. 1996;275(24):1915–1920 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taillieu T, Brownridge DA. Prevalence, patterns, and risk factors for experiencing intimate partner violence during pregnancy: a review of the literature and directions for future research. Aggress Violent Behav. 2010;15(1):14–35 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart D, Cecutti A. Physical abuse during pregnancy. CMAJ. 1993;149(9):1257–1263 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muhajarine N, D'Arcy C. Physical abuse during pregnancy: prevalence and risk factors. CMAJ. 1999;160(7):1007–1011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janssen PA, Holt VL, Sugg NK, Emanuel I, Critchlow CM, Henderson AD. Intimate partner violence and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a population based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(5):1341–1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung WC, Leung TW, Lam YYJ, Ho PC. The prevalence of domestic violence against pregnant women in a Chinese community. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;66(1):23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shumway J, O'Campo P, Gielen A, Witter FR, Khouzami AN, Blakemore KJ. Preterm labor, placental abruption, and premature rupture of membranes in relation to maternal violence or verbal abuse. J Matern Fetal Med. 1999;8(3):76–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bacchus L, Mezey G, Bewley S. A qualitative exploration of the nature of domestic violence in pregnancy. Violence Against Women. 2006;12(6):588–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farid M, Saleem S, Karim MS, Hatcher J. Spousal abuse during pregnancy in Karachi, Pakistan. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;101(2):141–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson JK, Haider F, Ellis K, Hay DM, Lindow SW. The prevalence of domestic violence in pregnant women. BJOG. 2003;110(3):272–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thananowan N, Heidrich SM. Intimate partner violence among pregnant Thai women. Violence Against Women. 2008;14(5):509–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Campo P, Gielen AC, Faden RR, Kass N. Verbal abuse and physical violence among a cohort of low-income pregnant women. Womens Health Issues. 1994;4(1):29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charles P, Perreira KM. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and 1-year post-partum. J Fam Violence. 2007;22(7):609–619 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo SF, Wu JL, Qu CY, Yan RY. Physical and sexual abuse of women before, during, and after pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;84(3):281–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson H. Assessing the prevalence of violence against women in Canada: expert paper. In: Violence Against Women: A Statistical Overview, Challenges and Gaps in Data Collection and Methodology and Approaches for Overcoming Them: Expert Group Meeting. Geneva, Switzerland: UN Division for the Advancement of Women in collaboration with Economic Commission for Europe and World Health Organization; 2005. Available at: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/egm/vaw-stat-2005/docs/expert-papers/johnson.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2011.

- 35.McFarlane J, Soeken K, Campbell J, Parker B, Reel S, Silva C. Severity of abuse to pregnant women and associated gun access of the perpetrator. Public Health Nurs. 1998;15(3):201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonomi AE, Holt VL, Thompson RS, Martin DP. Ascertainment of intimate partner violence in women seeking legal protection. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(1):52–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reichenheim M, Moraes C. Comparison between the abuse assessment screen and the revised conflict tactics scales for measuring physical violence during pregnancy. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(6):523–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parker B, McFarlane J. Nursing assessment of the battered pregnant woman. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 1991;16(3):161–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Straus M. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. J Marriage Fam. 1979;41(1):75–88 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Straus M, Hamby S, Boney-McCoy Set al. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dzakpasu S, Kaczorowski J, Chalmers Bet al. The Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey: design and methods. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30(3):207–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Maternity Experiences Survey, 2006 Questionnaire. Ottawa, Ontario: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2009.

- 43.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. CIHR guidelines for health research involving Aboriginal peoples. 2007. Available at: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/ethics_aboriginal_guidelines_e.pdf. Accessed May 9, 2011.

- 44.Appendix B: Ethical Guidelines for Research. Ottawa, Ontario: Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Statistics Canada. Canadian Violence Against Women Survey. 1993. Available at: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/cgi-bin/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=3896&lang=en&db=imdb&adm=8&dis=2#a1. Accessed March 25, 2011.

- 46.Statistics Canada Census Dictionary Catalogue no.92-566-X 2010. Ottawa, Ontario: Minister of Industry; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 47.SAS/STAT 9.2 User's Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin S, Mackie L, Kupper L, Bacchus L, Maracco K. Physical abuse of women before, during, and after pregnancy. JAMA. 2001;285(12):1581–1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malcoe LH, Duran BM, Montgomery JM. Socioeconomic disparities in intimate partner violence against Native American women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med. 2004;2:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Covington DL, Hage M, Hall T, Mathis M. Preterm delivery and the severity of violence during pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 2001;46(12):1031–1039 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heaman M. Relationships between physical abuse during pregnancy and risk factors for preterm birth among women in Manitoba. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005;34(6):721–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dunn LL, Oths KS. Prenatal predictors of intimate partner violence. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004;33(1):54–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fanslow J, Silva M, Robinson E, Whitehead A. Violence during pregnancy: associations with pregnancy intendedness, pregnancy-related care, and alcohol and tobacco use among a representative sample of New Zealand women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48(4):398–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andersson N, Nahwegahbow A. Family violence and the need for prevention research in First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities. Pimatisiwin. 2010;8(2):9–33 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anderson K. Marriage, divorce and the family life. : Cannon MJ, Sunseri L, Racism, Colonialism and Indigeneity in Canada: A Reader. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2011:113–119 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hyman I, Forte T, Du Mont J, Romans S, Cohen M. Help-seeking behavior for intimate partner violence among racial minority women in Canada. Womens Health Issues. 2009;19(2):101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abraham M. Speaking the unspeakable: marital violence against South Asian immigrant women in the United States. Indian J Gend Stud. 1998;5:215–241 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Menjivar C, Salcido O. Immigrant women and domestic violence: common experiences in different countries. Gend Soc. 2002;16(6):898–920 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hyman I, Forte T, Du Mont J, Romans S, Cohen MM. The association between length of stay in Canada and intimate partner violence among immigrant women. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):654–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gielen A, O'Campo P, Faden R, Kass N, Xue N. Interpersonal conflict and physical violence during the childbearing year. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(6):781–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O'Campo P, Kirst M, Tsamis C, Chambers C, Ahmad F. Implementing successful intimate partner violence screening programs in health care settings: evidence generated from a realist-informed systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(6):855–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Díaz-Olavarrieta C, Paz F, Abuabarak K, Martínez AHB, Kolstad K, Palermo T. Abuse during pregnancy in Mexico City. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;97(1):57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O'Campo P, Ahmad F, Cyriac A. Role of healthcare professionals in preventing and intervening on IPV. In: Keeling J, Mason T, eds. Domestic Violence: A Multi-Professional Approach for Healthcare Practitioners. Berkshire, England: Open University Press; 2008:107–115.

- 64.Martin SL, Harris-Britt A, Li Y, Moracco KE, Kupper LL, Campbell JC. Changes in intimate partner violence during pregnancy. J Fam Violence. 2004;19(4):201–210 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saftlas AF, Wallis AB, Shochet T, Harland KK, Dickey P, Peek-Asa C. Prevalence of intimate partner violence among an abortion clinic population. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1412–1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K. Abuse during pregnancy: associations with maternal health and infant birth weight. Nurs Res. 1996;45(1):37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rennison C, Welchans S. Intimate Partner Violence. Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice; 2000. Available at: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/ipv.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Clark J, Du Mont J. Intimate partner violence: a critique of Canadian prevalence studies. Can J Public Health. 2003;94(1):52–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Coker A, Smith P, Bethea L, King M, McKeown R. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(5):451–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]