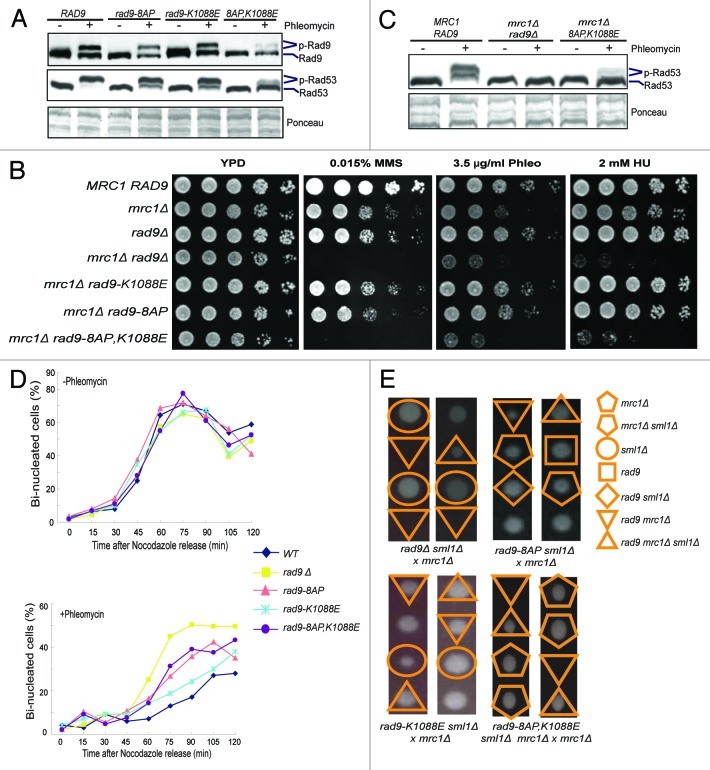

Figure 4. N-terminal and C-terminal SP/TP sites of Rad9 act redundantly to control DNA damage checkpoint activation. Gel mobility shift assays of Rad9–3HA and Rad53 were performed using G2/M-arrested cells and asynchronous cells as indicated in (A and C), respectively. (B) Plate sensitivity assay of WT, mrc1Δ, rad9Δ and various double mutants of mrc1Δ rad9. (D) Percentages of bi-nucleated cells after release from phleomycin treatment in the G2/M phase, comparing WT, rad9Δ, rad9–8AP, rad9-K1088E and rad9–8AP,K1088E mutants. (E) Tetrad dissection analysis of the genetic interactions between various rad9 mutants, mrc1Δ and sml1Δ. Synthetic lethality between mrc1Δ and either rad9Δ or rad9–8AP,K1088E is rescued by sml1Δ. No synthetic lethality was detected between mrc1Δ and rad9–8AP or rad9-K1088E. Representative tetrads are shown here for simplicity. Unmarked spores contain RAD9 MRC1 SML1.

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov website belongs to an official

government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock (

) or https:// means you've safely

connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive

information only on official, secure websites.