Abstract

In 2007, the Current Population Survey (CPS) introduced a measure that identifies all cohabiting partners in a household, regardless of whether they describe themselves as “unmarried partners” in the relationship to householder question. The CPS now also links children to their biological, step-, and adoptive parents. Using these new variables, we analyze the prevalence of cohabitation as well as the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of different-sex cohabiting couples during the years 2007–2009. Estimates of cohabitation produced using only unmarried partnerships miss 18 % of all cohabiting unions and 12 % of children residing with cohabiting parents. Although differences between unmarried partners and most newly identified cohabitors are small, newly identified cohabitors are older, on average, and are less likely to be raising shared biological or adopted children. These new measures also allow us to identify a small number of young, disadvantaged couples who primarily reside in households of other family members, most commonly with parents. We conclude with an examination of the complex living arrangements and poverty status of American children, demonstrating the broader value of these new measures for research on American family and household structure.

Keywords: Cohabitation, Measurement, Living Arrangements, Stepfamilies, Poverty

Introduction

The rise of cohabitation has dramatically reshaped American family life. Nearly non-existent in 1960, the number of cohabiting couples increased to 7.5 million by 2010 (Fitch et al. 2005; Kreider 2010). More than two-thirds of American adults cohabit before they marry, and about 40 % of children live in a cohabiting family during childhood (Kennedy and Bumpass 2008). The development of large and consistent data sources collected at regular intervals to study cohabitation has lagged behind these shifts in family structure (Casper and Hofferth 2007). The paucity of regular data on cohabiting families is particularly problematic for the study of children’s living arrangements and the assessment of children’s well-being.

The Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) to the Current Population Survey (CPS) is the primary source of annual data on the structure and economic well-being of American families (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). Until 2007, only persons who reported themselves as “unmarried partners” of the householder1 could be identified as cohabitors. This measure has two limitations. First, couples who do not recognize the term “unmarried partner” can be missed. Second, unions in which neither partner is identified as the householder are excluded. Measurement of family relationships in the CPS was greatly improved in 2007 by the introduction of direct questions identifying all cohabiting couples and linking children to their biological, step-, and adoptive parents.

Using the 2007–2009 ASEC surveys, we examine the impact of these family relationships measures on estimates of the prevalence and characteristics of cohabiting families and couples. Because unmarried partners are the only identifiable cohabiting couples in the decennial census, the American Community Survey (ACS), and earlier years of the CPS, we also assess whether couples identified using the unmarried partner measurement differ demographically or socioeconomically from newly identified cohabiting couples. We examine in detail the living arrangements of cohabiting couples, including residence with children, parents, other relatives, and nonrelatives. In addition, we use the detailed measures of income and family structure in the ASEC to examine the economic well-being of cohabiting couples. Finally, we document the diversity of children’s living arrangements by describing family structure, stepfamily and extended family residence, and child poverty rates in married, cohabiting, and single-parent families.

Background

Much of what we know about cohabitation comes from family surveys. Prior to 1987, no nationally representative statistics existed on cohabitation. The 1987 National Survey of Families and Households was the first survey to collect detailed cohabitation histories. The periodic National Survey of Family Growth has collected cohabitation histories since 1988, but data until recently were limited to women of reproductive age. The Fragile Families survey, a study of children born to urban unmarried parents during 1998–2000, provides important longitudinal data on these families. Although valuable sources of cohabitation data, family surveys are often limited by small or nonnationally representative samples of cohabitors, infrequent data collection, or limited information on family economic well-being. In addition, because family surveys often employ different methods for identifying cohabitors, results may not be directly comparable across surveys (Hayford and Morgan 2008; Knab and McLanahan 2007; Pollard and Harris 2007; Teitler et al. 2006).

Until 1990, researchers using population censuses and surveys had to infer cohabitation status based on the coresidence of people of the opposite sex, which proves to be an extremely imprecise method (Casper and Cohen 2000; Fitch et al. 2005). In 1990, the U.S. Census Bureau added “unmarried partner” as a category in the question asking “relationship to the householder.” When the CPS was updated with similar language in 1995, detailed data on the prevalence of cohabiting families became available annually. However, this approach still failed to identify some cohabiting couples. Because most cohabitors do not use the term “unmarried partner” to describe their relationship—instead, preferring identifiers such as “boyfriend” or “fiancée”— many couples are potentially missed by this measure (Manning and Smock 2005). In addition, unions not involving the householder (e.g., couples residing with parents or roommates) could not be identified. The new question in the CPS allows us to assess how many couples fall into these two categories.

CPS and census data were also limited in their ability to measure the living arrangements and economic well-being of cohabiting families. Prior to 2007, annual Census Bureau estimates of children’s family structure counted children of cohabiting couples as though they were raised by a single parent (Kreider 2008). Currently, about 40 % of cohabiting couples are raising resident children, and these households would have been classified as mother-only or father-only families. This definition is still in use today by the Census Bureau when calculating official family poverty statistics. Treating cohabiting families as single-parent families excludes the income of the cohabiting partners from poverty calculations and substantially underestimates the economic well-being levels in cohabiting families (Iceland 2007; Manning and Brown 2006). The most recent attempts to calculate cohabiting family incomes and associated poverty levels are a decade out of date, when data sets containing detailed information on income and cohabiting family relationships were last available (Iceland 2007; Manning and Smock 2005).

In 2007, the CPS questionnaire was revised to improve the measurement of cohabitation and family relationships (Kreider 2008). The CPS questionnaire begins by enumerating all usual residents of the sampled household2 as well as persons with no usual residence who are staying in the household. Each person is assigned a line number that represents their position (or line) on the household roster. Subsequently, the interviewer collects demographic data on household members, including relationship to the householder, age, and sex (U.S. Census Bureau 2008a). A direct question on cohabitation was added to this section of the interview. In households with unrelated adults, unmarried respondents are asked, “Do you have a boyfriend, girlfriend or partner in this household?” If the response was yes, the respondent was then asked to identify the cohabiting partner, and the interviewer recorded the partner’s line number. The same question was posed about all other unmarried adults in the household except persons identified as an unmarried partner in the relationship to householder variable. Estimates of the number of different-sex cohabiting couples increased by more than 20 % as a result of the new cohabitation question (Kreider 2008).3

Because the cohabitation question is asked only of household members, it will not identify couples who live together some of the time but maintain separate residences. The more restrictive definition of the household membership in the CPS approach will yield lower estimates of cohabitation than surveys that include part-time or visiting relationships (Knab and McLanahan 2007; Pollard and Harris 2007).

Before 2007, the CPS also collected limited information on parent-child relationships: interviewers recorded the line number of one parent or stepparent based on relationship to householder and the interviewer’s “knowledge of the family structure.” Thus, researchers could not determine whether a child was related biologically to both partners or to only one partner. In 2007, the Census Bureau expanded the data collected on parent-child relationships. The CPS now includes both mother and father line numbers and distinguishes between biological, step-, and adoptive parents (Kreider 2008).4 With these new variables, the CPS provides detailed annual data on the cohabitation experiences of children and adults.

Table 1 illustrates two hypothetical cohabiting household rosters to demonstrate the new family locator variables.5 The top household presents a newly identified cohabiting union involving the householder: prior to the availability of the new cohabitation question, the union between the woman and her male roommate was invisible. Now they are linked by the partner locator variable. In addition, it is evident from the parent locator variables that one of the children is the shared biological child of the cohabiting couple. A second child is linked to the female partner but not to the male partner, and is likely the mother’s child from a previous relationship. In the second household, the new questions reveal a cohabiting couple residing with their own child within the household of the female partner’s parents.

Table 1.

Households illustrating the new CPS cohabiting partner and parent locator variables

| New family locator variables |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship to Householder |

Line Number |

Age | Sex | Cohabiting Partner Location |

Mother’s Location |

Mother’s Relationship |

Father’s Location |

Father’s Relationship |

| 1. Newly Identified Householder Unionsa | ||||||||

| Householder | 1 | 32 | F | 2 | ||||

| Roommate | 2 | 30 | M | 1 | ||||

| Child | 3 | 5 | F | 1 | Biological | |||

| Child | 4 | 1 | M | 1 | Biological | 2 | Biological | |

| 2. Newly Identified Subfamily Unionsb | ||||||||

| Relationship to Householder |

||||||||

| Householder | 1 | 47 | M | |||||

| Spouse | 2 | 46 | F | |||||

| Child | 3 | 18 | F | 4 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Nonrelative | 4 | 18 | M | 3 | ||||

| Grandchild | 5 | 0 | M | 3 | Biological | 4 | Biological | |

Newly identified unions between the householder and a person identified as a roommate or other nonrelative.

Newly identified unions between two persons who are not householder.

Data and Methods

We use data from the 2007–2009 ASEC of the CPS, provided by the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series at http://cps.ipums.org (King et al. 2010). The ASEC collects detailed data on income, employment, and noncash benefits, and is the source for annual census reports on Families and Living Arrangements. Our analysis includes nearly 9,000 different-sex cohabiting couples and more than 95,000 children.6

Our goals are to describe the prevalence and characteristics of cohabiting couples and families with children and to assess the impact of the new cohabitation and family relationship variables. Consequently, the methods used are descriptive in nature. We consider a broad array of demographic and socioeconomic correlates of cohabitation and incorporate information on all family members.

Variables

Cohabitation Measurement

Our analysis distinguishes the newly identified cohabiting unions from unmarried partnerships. We separate cohabiting unions into the following categories:

-

Householder unions: Relationships involving the householder, the person (or one of the people) in whose name the housing unit is owned or rented.

(1a) Unmarried partner unions: Unions between the householder and his or her unmarried partner (identified through relationship to the householder variable). These cohabitors could be identified before the introduction of a direct question on cohabitation.

(1b) Newly identified householder unions: Unions between the householder and a nonrelative in the household who is not identified as an unmarried partner. These couples are identified only as a result of the direct question on cohabitation.

Subfamily cohabiting unions: Newly identified unions between two people in the household, neither of whom is the householder. These subfamilies should not be confused with census-defined subfamilies, which would not include cohabiting partners.

Previous research has revealed differences between unmarried partner unions (1a) and the newly identified unions (1b and 2 combined) (Kreider 2008), but we differentiate across all three types. We expect significant differences between the two major categories: householder (1a and 1b) and subfamily unions (2). The distinction that we make between the two types of householder unions (1a and 1b) is the result of measurement and is not meant to imply conceptually different types of relationships. Nonetheless, it is critical to examine how representative unmarried partners are of all cohabitors because the unmarried partner variable is the only measure of cohabitation in the ACS.

Parent-Child Relationships

Our analysis distinguishes between couples raising shared children and couples who are raising the children of one partner only. We define “shared children” to be children who are biologically related to or adopted by both cohabiting partners. “Stepchildren” are children who are identified as the biological child or adopted child of one parent and as the stepchild of or as unrelated to the cohabiting partner.7 We then categorize couples into six mutually exclusive groups:

No children: The couple have no children.

Shared children only: The couple are raising only shared biological or adopted children.

Shared and stepchildren: The couple are raising both shared and stepchildren.

Female partner’s only: The couple are raising the biological or adopted child(ren) of the female partner only and have no shared children.

Male partner’s only: The couple are raising the biological or adopted child(ren) of the male partner only and have no shared children.

Stepchildren of both partners: The couple are raising the biological or adopted child(ren) of the male partner and the biological or adopted child(ren) of the female partner. The couple have no shared children.

Demographic Characteristics of Cohabiting Partners

We examine variation between couples in partner ages and marital status. We also compare the race, ethnicity, and nativity of each partner as well as metropolitan status, geographic region, and residential history.

Although the CPS allows respondents to report multiple races, the number of multiracial cohabitors is too small to analyze separately. Instead, we apply race-bridging methods to predict the single race category that a person would most likely have reported if (s)he could report only one race (Liebler and Halpern-Manners 2008). Our final measure identifies the most common combinations of partner races.

Socioeconomic Status

We examine the education level of each partner as well as school enrollment and employment status. We also consider family poverty levels, measured as the ratio of family income to needs. We base our estimates of poverty status on the federal poverty thresholds (U.S. Census Bureau 2006, 2007, 2008b).8 Our measures of poverty differ from the official poverty measurements because we treat cohabiting partners as members of the same family. Including cohabiting partner incomes in family poverty measurements more completely accounts for the economic resources available in cohabiting families and thus substantially reduces estimated poverty rates (Carlson and Danziger 1999; Iceland 2007; Manning and Brown 2006).

We calculate income-to-needs poverty in two ways:

Couple poverty ratio: In this measure, we calculate total family income by using the cohabiting couple’s income, plus any income contributed by their adult children. In addition, only the couple and their children are used to calculate family size. The ratio of the couple’s income to the poverty threshold for their family size is our first measure of family poverty. We construct a similar parent/child poverty measure for children in married, cohabiting, and single-parent families.

Total family poverty ratio: The second approach is more traditional and includes other relatives who live in the household in calculations of family income and family size. The difference between this measure and the couple poverty ratio helps identify the extent to which couples benefit financially from residing with extended family.

We then classify each couple and each child into one of four categories: in poverty (income is less than 100 % of the poverty threshold), 100 %–199 % of the poverty threshold, 200 %–299 % of the poverty threshold, and 300 % and more of the poverty threshold.

Analytic Approach

We begin by examining the impact of the direct cohabitation question on estimates of cohabitation. To evaluate whether newly identified cohabitors differ significantly from unmarried partners, we consider the living arrangements as well as the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of unmarried partner unions, newly identified householder unions, and subfamily cohabiting unions. Multinomial logistic regression models produce similar results and are available in Online Resource 1; important differences are noted in the text. We conclude with an analysis of the living arrangements and poverty status of children younger than 15.

Variance estimates calculated from the ASEC must take into account the complex sample design of the ASEC. The Census Bureau developed a set of 160 replicate weights that adjust for clustering and stratification (Fay and Train 1995). We employ Stata survey procedures to calculate variances, using the replicate weights.9

We include multiple years of the ASEC to maximize our sample size. The CPS sampling strategy introduces complexities when pooling multiple years. The CPS identifies housing units, not individuals, for inclusion in the sample; it then conducts surveys from residents of selected households for four months in a row, breaks for eight months, and then collects data for an additional four months. If respondents move, the CPS does not follow them, instead collecting information on new residents at the address. Because we pool three years of data, the same individuals can appear twice. To avoid including duplicate individuals, our analysis includes all respondents to the 2008 ASEC, year 2007 respondents in Months 5–8 of the interview cycle, and year 2009 respondents in Months 1–4 of the interview cycle.

Our analysis includes data collected 15 months after the recession began in December 2007. The prevalence of the different types of cohabiting unions is unchanged between the 2009 ASEC and earlier ASEC samples. Poverty rates increased by 1 percentage point between the 2008 and 2009 samples (U.S. Census Bureau 2009).

Results

Prevalence and Family Structure of Cohabiting Couples

Table 2 presents estimates of the proportion of all U.S. adults who were living in a cohabiting union broken down by age groups and type of cohabiting union.10 Overall, 6 % of U.S. adults (ages 15+) were cohabiting with a different-sex partner. Most cohabitors (82 %) selected “unmarried partner” in the relationship to the householder question and would have been identified without the new cohabitation question. The remaining couples are newly identified: 11 % were in a union between the householder and a nonrelative; and 6 % were in a union between two household members, neither of whom was the householder. Of the roughly 6.7 million different-sex couples cohabiting in 2008, 5.4 million were unmarried partners. Of the 1.25 million newly identified cohabitors, roughly 850,000 are householder unions (relationships including the householder), and 400,000 are subfamily cohabiting unions, residing in the households of parents, other relatives, or nonrelatives.

Table 2.

Percentage of adults in a different-sex cohabiting union by age and union type

| Newly Identified Unions (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Cohabiting Unions (%) |

Unmarried Partner Unionsb (%) |

Newly Identified Householder Unionsc |

Subfamily Cohabiting Unionsd |

% of Unions Newly Identified |

|

| Agea | |||||

| 15–19 | 1.78 | 1.14 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 36 |

| 20–29 | 12.38 | 10.00 | 1.29 | 1.09 | 19 |

| 30–39 | 7.65 | 6.52 | 0.79 | 0.34 | 15 |

| 40–49 | 5.15 | 4.40 | 0.58 | 0.17 | 15 |

| 50+ | 2.50 | 2.05 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 18 |

| Total | 5.52 | 4.54 | 0.63 | 0.34 | 18 |

| Unweighted n (adults) | 313,188 | 313,188 | 313,188 | 313,188 | 17,588 |

| Unweighted n (cohabitors) | 17,588 | 14,668 | 1,872 | 1,048 | 17,588 |

The unit of analysis in this table is the person and age reflects each individual’s age. Both males and females are included. Later tables will treat cohabiting couples as units of analysis and age will be measured at the couple level.

Unions between the householder and a person identified as their unmarried partner.

Newly identified unions between the householder and a person identified as a roommate or other nonrelative.

Newly identified unions between two persons who are not householders.

Source: Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey, 2007–2009.

The new cohabitation measure substantially improves estimates of cohabitation prevalence at all ages. Teenage cohabitation is rare but is the most likely to be missed by unmarried partner measures; of the 2 % of teens who are currently cohabiting, one-third are newly identified, primarily in subfamily unions. Cohabitation peaks among adults in their twenties, at 12 % of all individuals ages 20–29. At these ages, the unmarried partner measure misses nearly one-fifth of consensual unions, and nearly one-half of newly identified couples reside in a subfamily. The new direct cohabitation question improves CPS estimates of the prevalence of cohabitation by 15 % for cohabitors between 30 and 50, and by nearly 20 % at older ages. For older cohabitors, subfamily unions are extremely rare.

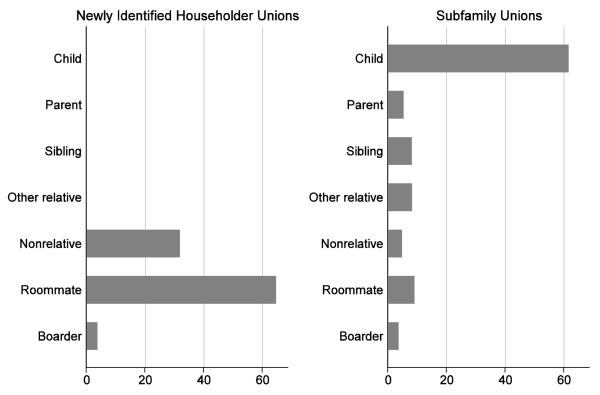

Who are these newly identified cohabitors? Figure 1 presents information on the relationship between the householder and the cohabiting couple. When one partner is the householder (“newly identified householder unions”), we report the relationship of the nonhouseholder partner. Usually, the partner is identified as a housemate or roommate (65 %). The remaining partners are identified as an “other nonrelative” of the householder (31 %) or a boarder (5 %). When unions occur between two individuals who are not the householder (“subfamily cohabiting unions”), we report the relationship of the partner most closely related to the householder. Typically, the couple resides with relatives. About 60 % of subfamily cohabiting unions involve a child of the householder, and an additional 25 % involve a sibling or other related person. Just 15 % of subfamily unions involve two persons unrelated to the householder, who are identified as roommates, nonrelatives, or boarders.

Fig. 1.

Relationship of newly identified cohabiting partner to the householder. For subfamily cohabitors, we report the relationship of the partner most closely related to the householder. Newly identified unions in the left panel are those between the householder and a person identi-fied as a roommate or other nonrelative. Newly identified unions on the right panel are those between two persons who are not householders. Source: Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey, 2007–2009

Previous qualitative research suggests that the proportion of cohabitors who ever live with roommates or adult relatives might exceed one-third (Manning and Smock 2005). In this cross-sectional snapshot of full-time cohabiting couples, we find that just 17 % of cohabitors reside with adults other than their own children, and only 6 % reside with unrelated roommates.

The new CPS variables are especially valuable for researchers studying complex household and family relationships. We demonstrate the rich information available on coresidence in Table 3, which describes the living arrangements of cohabiting couples. The first panel describes the distribution of cohabiting couples across three mutually exclusive household compositions: couple-only, couple and their children only, and couple living with other relatives or nonrelatives (regardless of whether children are present). The second panel examines the presence of children and their relationship to the couple (shared or stepchild), using the mutually exclusive categories described earlier. The final panel reports the percentage of cohabiting couples residing with parents, other relatives, or nonrelatives; in this section, couples can fall into multiple categories. The CPS household roster allows us to identify all persons related to the householder. For persons unrelated to the householder, only relatives who are linked through spouse, cohabiting partner, or parent-child pointers can be identified. Consequently, estimates in Table 3 overstate the number of nonrelatives residing with the cohabiting couple.

Table 3.

Living arrangements of cohabiting couples

| Unmarried Partner Unionsa (%) |

Newly Identified Householder Unionsb(%) |

Subfamily Cohabiting Unionsc (%) |

Total (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Household Composition | ||||

| Couple-only household | 52 | 54 | n/a | 49 |

| Couple and children only | 36 | 32* | 5* | 34 |

| Couple lives with other persons | 11 | 13 | 95* | 17 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| B. Residence With Children | ||||

| No children | 58 | 62 | 70* | 60 |

| Shared biological/adopted children | ||||

| Shared children only | 16 | 9* | 10* | 15 |

| Shared and stepchildren | 6 | 3* | 3* | 5 |

| Stepchildren only | ||||

| Female partner’s only | 14 | 21* | 12 | 15 |

| Male partner’s only | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Stepchildren of both partners | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| C. Residence With Other Family/Nonfamilyd | ||||

| Parents | 2 | 4* | 64* | 6 |

| Other relatives | 5 | 5 | 52* | 8 |

| Nonrelatives/unknown | 5 | 5 | 19* | 6 |

| Unweighted n (couples) | 7,334 | 936 | 524 | 8,794 |

Note: The unit of analysis is the couple.

Unions between the householder and a person identified as their unmarried partner.

Newly identified unions between the householder and a person identified as a roommate or other nonrelative.

Newly identified unions between two persons who are not householders.

Living arrangements are not mutually exclusive: for example, a couple can live with their parents and other relatives.

Source: Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey, 2007–2009.

Significantly different from estimate for unmarried partners (p < .05)

Householder couples—that is, unions involving the householder and their partner—reside primarily in nuclear families; just over one-half reside in couple-only households, and an additional one-third reside with their children and no other persons. Of these couples, unmarried partners are significantly more likely to reside with their children and no other persons than newly identified householder partners (36 % vs. 32 %). In total, 40 % of householder couples live with the children of one or both partners. Unmarried partners, however, are nearly twice as likely to have shared biological or adopted children as couples in newly identified householder unions (22 % vs. 12 %). Unmarried partners are also less likely to be raising only those children related to a single partner (20 % vs. 26 %). These differences are robust to controls for age and marital status. Less than 5 % of couples in householder unions reside with their parents; 5 % reside with other relatives, such as siblings; and 5 % reside with someone unrelated to both partners. With the exception of parent-child relationships, differences between unmarried partner unions and newly identified householder unions are small.

Subfamily cohabitors, by definition, cannot live alone. Only 5 % live with only their children, and in these households, an adult child is identified as the householder. The vast majority (more than 80 %) live only with relatives. Of these, two-thirds reside with parents; one-third reside with their own children; and one-half reside with other relatives—most commonly, siblings. Less than 20 % live with nonrelatives. There is considerable overlap between these family situations: 16 % of subfamily cohabitors live with both parents and children, 34 % live with parents and other relatives, and 9 % live with both related and unrelated persons. These living arrangements differ significantly from householder unions.

The living arrangements of subfamily partners raising children differ significantly from childless subfamily partners (p < .05). In general, subfamily cohabitors are more likely to reside with the male partner’s parents than the female partner’s parents (37 % vs. 26 %). Couples raising children, however, are more likely to reside with the female partner’s family: 35 % compared with 20 % with male partner’s family. The breakdown for childless couples was 25 % with her family and 43 % with his family. Family coresidence patterns appear to follow the gendered nature of caregiving, suggesting that assistance with child care may be an important reason couples reside with the female partner’s family.

Demographic Characteristics of Cohabiting Couples

We present data on the demographic characteristics of unmarried partners and newly identified cohabitors in Table 4. Subfamily cohabiting unions differ substantially from householder unions more generally, and the differences between householder unions (unmarried partner unions and newly identified householder unions) are smaller.

Table 4.

Demographic characteristic of cohabitors by type of cohabiting union

| Unmarried Partner Unionsa (%) |

Newly Identified Householder Unionsb(%) |

Subfamily Unionsc (%) |

Total(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Couple Age Distribution | ||||

| Age of younger partner | ||||

| 15–19 years | 3.8 | 3.8 | 19.0* | 4.8 |

| 20–29 | 45.6 | 40.0* | 56.9* | 45.7 |

| 30–39 | 21.5 | 19.5 | 12.9* | 20.7 |

| 40–49 | 16.8 | 18.7 | 8.5* | 16.5 |

| 50+ years | 12.3 | 18.0* | 2.7* | 12.3 |

| Female is older | 27.2 | 32.3* | 24.0 | 27.6 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Both never married | 48.9 | 42.3* | 69.4* | 49.5 |

| One partner ever-married | 23.0 | 24.8 | 19.4 | 23.0 |

| Both ever-married | 28.1 | 32.9* | 11.2* | 27.5 |

| Race, Ethnicity, and Nativity | ||||

| Hispanic origin | ||||

| Neither Hispanic | 81.4 | 83.3 | 76.3* | 81.3 |

| One partner Hispanic | 8.2 | 9.6 | 6.6 | 8.2 |

| Both Hispanic | 10.5 | 7.0* | 17.1* | 10.5 |

| Couple race | ||||

| Both American Indian | 0.9 | 0.3* | 1.9 | 0.9 |

| American Indian and White | 0.9 | 1.3 | 2.3* | 1.0 |

| Both Asian | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 1.6 |

| Asian and White | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.8 |

| Both Black | 10.8 | 11.9 | 6.4* | 10.6 |

| Black and White | 3.7 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 3.6 |

| Both White | 79.9 | 79.5 | 82.0 | 80.0 |

| Other | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.4 |

| Either partner is foreign born | 14.2 | 12.4 | 16.1 | 14.1 |

| Additional Characteristics | ||||

| Residential history | ||||

| Neither moved | 68.6 | 65.7 | 67.6 | 68.2 |

| Both moved | 25.7 | 26.7 | 18.2* | 25.3 |

| Different history | 5.8 | 7.6 | 14.2* | 6.5 |

| Metropolitan area | 82.4 | 84.9 | 79.2 | 82.5 |

| Region | ||||

| New England | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.8 | 5.0 |

| Mid-Atlantic | 12.5 | 11.4 | 9.1* | 12.1 |

| East North Central | 15.9 | 15.2 | 18.5 | 16.0 |

| West North Central | 7.7 | 9.6 | 5.7* | 7.8 |

| South Atlantic | 19.1 | 21.2 | 14.5* | 19.0 |

| East South Central | 5.4 | 6.3 | 5.1 | 5.5 |

| West South Central | 9.0 | 9.6 | 10.9 | 9.2 |

| Mountain | 8.0 | 8.5 | 7.1 | 8.0 |

| Pacific | 17.6 | 13.1* | 23.4* | 17.5 |

| Survey year | ||||

| 2007 | 24.6 | 23.9 | 22.2 | 24.4 |

| 2008 | 50.4 | 52.6 | 48.4 | 50.5 |

| 2009 | 25.0 | 23.5 | 29.4 | 25.1 |

| Unweighted n (couples) | 7334 | 936 | 524 | 8,794 |

Note: The unit of analysis is the couple.

Unions between the householder and a person identified as their unmarried partner.

Newly identified unions between the householder and a person identified as a roommate or other nonrelative.

Newly identified unions between two persons who are not householders.

Source: Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey, 2007–2009.

Significantly different from estimate for unmarried partners (p < .05)

The largest differences between the three types of cohabiting unions are found in age and marital status. The newly identified householder partners are, on average, older than unmarried partners: 18 % are 50 or older, compared with just 12 % of unmarried partners.11 In contrast, couples in subfamily couples are younger than unmarried partners. Nearly 20 % of subfamily cohabiting unions include a partner younger than 20; and in an additional 57 % of couples, the younger partner is in his or her 20s. For unmarried partners, these numbers are just 4 % and 46 %, respectively. Consistent with these age differences, newly identified householder partners are more likely to be ever-married than unmarried partners, but subfamily cohabitors are less likely.

Few other notable demographic differences exist. A higher proportion of subfamily cohabitors are both Hispanic compared with unmarried partners and newly identified householder partners, but these differences are not robust to multivariate analysis and likely reflect age differences in ethnicity. Most couples (about two-thirds) report living at the same address for at least one year. Couples in subfamily unions are more likely to report different residential histories, presumably because one partner is already living with family when the union begins.

Socioeconomic Characteristics of Cohabiting Couples

An important advantage of the new CPS family variables is that they improve the accuracy and detail with which the income and poverty status of cohabiting couples can be measured. In particular, when couples reside with extended family, we can examine the ability of a couple to support themselves and their children above the poverty level to the actual poverty levels they experience. Note that poverty estimates are based on income earned in the years 2006–2008 and largely predate the increase in poverty observed during the Great Recession, which began in December 2007.

In most respects—including income, education, and employment levels—unmarried partner unions and newly identified householder unions are extremely similar (see Table 5). Unmarried partner unions and newly identified householder unions differ significantly in only two instances: unmarried partners are less likely to both have a bachelor’s degree and are more likely to report near-poverty income (between 100 % and 200 % of poverty threshold) than higher incomes. The magnitude of these differences is small. Unmarried partner unions are highly representative of the socioeconomic characteristics of all unions involving the householder.

Table 5.

Socioeconomic characteristics of cohabitors by type of cohabiting union

| Unmarried Partner Unionsa |

Newly Identified Householder Unionsb |

Subfamily Unionsc |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| A. Education and Employment | ||||

| Educational attainment | ||||

| Both < high school | 6.8 | 6.4 | 14.4* | 7.3 |

| One < high school, no college graduate | 14.6 | 14.5 | 21.3* | 15.0 |

| Both high school graduate or some college | 50.5 | 48.5 | 53.2 | 50.5 |

| One college graduate (4 yrs.) | 17.4 | 16.5 | 7.1* | 16.6 |

| Both college graduate (4 yrs.) | 10.6 | 14.1* | 4.0* | 10.6 |

| Female more educated | 28.6 | 29.2 | 26.5 | 28.5 |

| Enrolled in school (either) | 8.1 | 7.4 | 12.7* | 8.3 |

| Female works full-time | 55.2 | 53.6 | 42.4* | 54.1 |

| Male works full-time | 68.9 | 65.2 | 62.1* | 68.0 |

| B. Poverty Status of Couples | ||||

| Couple poverty level: 2006–2008 | ||||

| 0–99 % of poverty threshold | 9.9 | 10.8 | 22.0* | 10.9 |

| 100–199 % | 18.3 | 14.6* | 29.3* | 18.5 |

| 200–299 % | 18.0 | 22.3* | 18.3 | 18.5 |

| 300%+ | 53.8 | 52.3 | 30.4* | 52.1 |

| Total family poverty level: 2006–2008 | ||||

| 0–99 % of poverty threshold | 9.6 | 10.2 | 8.9 | 9.6 |

| 100–199 % | 18.6 | 15.5* | 18.7 | 18.3 |

| 200–299 % | 17.9 | 22.4* | 21.5 | 18.7 |

| 300 %+ | 53.8 | 51.9 | 50.9 | 53.4 |

| C. Financial Assistance | ||||

| Couple receives regular financial assistance from outside household |

2.4 | 1.5 | 0.8* | 2.2 |

| Unweighted n (couples) | 7334 | 936 | 524 | 8,794 |

Note: The unit of analysis is the couple.

Unions between the householder and a person identified as their unmarried partner.

Newly identified unions between the householder and a person identified as a roommate or other nonrelative.

Newly identified unions between two persons who are not householders.

Source: Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey, 2007–2009.

Significantly different from estimate for unmarried partners (p < .05)

In contrast, subfamily cohabiting unions have significantly lower socioeconomic status (SES) than both types of householder unions. Subfamily cohabitors are less likely to have ever attended college or even to have finished high school. They are also less likely to be employed. These differences persist in multivariate models that control for age.

Based on couple incomes, we estimate that more than 20 % of subfamily cohabitors would live below the poverty level, compared with 10 % of unmarried partners and newly identified householder partners. Couples in subfamily unions are also significantly more likely to report near-poverty incomes. These differences in economic well-being remain significant even after we control for the younger age and lower educational attainment of subfamily cohabitors. Because subfamily couples usually reside with extended family, actual family poverty levels are comparable with those of householder unions.

The financial benefits of living with extended family are substantial. Median income in subfamily unions increases from $30,000 to $70,000 when contributions from all family members are considered. Although couples living in independent households could receive financial assistance from family and friends who live outside the household, just 2 % of couples in householder unions report regular financial assistance. Thus, the vast majority of cohabitors receive little or no regular financial assistance from families and friends, outside of the benefits of coresidence.

Children’s Living Arrangements and Economic Well-being

In Table 6, we demonstrate the value of these new variables for describing children’s family structure and assessing economic well-being.12 The majority (68 %) of children ages 0–14 live with two married parents. A small percentage (6 %) live with cohabiting parents; and of these, 12 % were newly identified using the direct question on cohabitation. An additional 23 % of children live with a single parent. Also, a very small percentage (3 %) live in a household without their parents, with grandparents, other relatives, or in a foster family; these children are not included in the Table 6.

Table 6.

Living arrangements and poverty status of children ages 0–14 living with parents

| Married parents |

Cohabiting parents |

Single parent |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| A. Lives With Two Biological/Adoptive Parents | 93.0 | 47.9* | n/a | n/a |

| B. Parent-Child Relationships in Two-Parent Families | ||||

| Family has shared biological/adopted children | ||||

| Shared children only | 87.0 | 35.8* | n/a | n/a |

| Shared and stepchildren | 9.5 | 22.4* | n/a | n/a |

| Family has stepchildren only | ||||

| Female partner’s only | 2.2 | 26.7* | n/a | n/a |

| Male partner’s only | 0.4 | 7.1* | n/a | n/a |

| Stepchildren of both partners | 0.9 | 8.0* | n/a | n/a |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | n/a | |

| C. Household Composition | ||||

| Parent(s) and children only | 91.2 | 87.0* | 71.5* | 86.3 |

| Lives with other relatives or nonrelatives | 8.8 | 13.0* | 28.5* | 13.7 |

| Grandparentsa | 4.1 | 4.2 | 18.9* | 7.6 |

| Other relativesa | 4.7 | 6.7* | 16.2* | 7.6 |

| Nonrelatives/Unknowna | 1.2 | 4.3* | 3.0* | 1.8 |

| D. Poverty Status: 2006–2008 | ||||

| Total family poverty | 9.2 | 19.7* | 39.2* | 17.0 |

| Parent-child povertyb | 9.7 | 21.3* | 47.9* | 19.6 |

| Unweighted n (children) | 68,621 | 5,990 | 21,195 | 95,806 |

Note: The unit of analysis is the child and includes only children living with at least one parent.

These categories are not mutually exclusive.

Calculated using the same method as couple poverty status.

Source: Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey, 2007–2009.

Significantly different from estimate for married parents (p < .05)

The parent-child relationship variables are especially useful for studying trends in family complexity, including stepfamily and extended-family residence, and highlight the much higher prevalence of stepfamilies and other complex families among cohabiting-couple households. The vast majority of children with two married parents (93 %) are the shared biological or adopted children of both parents, and only 13 % live in stepfamilies (in which some or all of the children are stepchildren). In contrast, just less than one-half of all children in cohabiting families live with two biological or adoptive parents, and nearly two-thirds live in stepfamilies. Among children in married stepparent families, nearly three-quarters live in a family that is also raising at least one shared child, but this is true of only one-third of children in cohabiting stepfamilies. Cohabiting families more often involve children from more than one partnership: 22 % of children with cohabiting parents live in a family with both shared and stepchildren, and another 8 % live in a family with children of both partners but no shared children. In married couple families, 10 % of children live in equally complex families. As researchers explore the implications of stepfamilies and multiple-partner fertility for child well-being, it will be important to use the CPS data to track the prevalence of these living arrangements (Carlson and Furstenberg, Jr. 2006; Guzzo and Furstenberg, Jr. 2007; Halpern-Meekin and Tach 2008).

The new CPS variables also demonstrate the complexity of living arrangements in single-parent families: 19 % live with a grandparent, and 16 % live with other relatives, with overlap between these categories. In total, 29 % of children in single-parent families reside with persons other than their parents and siblings, compared with 9 % of children with married parents and 13 % of children with cohabiting parents.

The final panel of Table 6 displays child poverty rates in 2006–2008 by family structure, using the two measures described earlier: total family and parent-child poverty. Living with grandparents and other relatives provides a substantial boost to the economic well-being of children in single-parent families; without the income contributed by extended family, 48 % would live in poverty. Overall, 17 % of children live under the poverty line using the total family measure. As found in previous research, poverty in cohabiting families falls between married-parent and single-parent families; 9 % of children in married families, 20 % in cohabiting families, and nearly 40 % in single-parent families live below the poverty threshold. These estimates are similar to 1998 poverty rates (Manning and Brown 2006), and the impact of the December 2007 recession was not yet apparent in these poverty calculations. The new CPS variables will be particularly useful for tracking child poverty rates through business cycles.

Discussion

This article uses newly developed measures of cohabitation and family relationships in the CPS to provide an up-to-date portrait of U.S. cohabitation and family structure. Using these new measures, we estimate that 6 % of U.S. adults were cohabiting with a different-sex partner, representing about 6.7 million couples in March 2008. Most adult cohabiting unions (82 %) are identified through the relationship to householder question (unmarried partners), but a substantial minority (18 %) are identifiable only with the addition of a direct question on cohabitation. Surveys without this question, like the ACS and the decennial census, will substantially underestimate the prevalence of cohabitation. The unmarried partners identified in these surveys may not be representative of all cohabiting couples. Addressing this issue required examining two distinct groups of newly identified cohabitors.

One group of newly identified cohabitors—the group that we label “subfamily cohabitors”—cannot be captured by the unmarried partner measure because neither partner is identified as a householder. These couples represent 6 % of all cohabitors and 33 % of the newly identified cohabitors. The other group—“newly identified householder cohabitors”—has a household structure similar to unmarried partners (a householder and cohabiting partner) and represents a larger share of cohabitors: 11 % of the total and 66 % of newly identified cohabitors.

Our analysis reveals some limitations in using “unmarried partners” as a proxy for all householder cohabiting partners. These newly identified householder couples are slightly older than those in unmarried partner unions. They are also substantially less likely to be raising shared biological or adopted children but more likely to be raising stepchildren. In nearly all other respects, across a variety of socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, the couples who identify themselves as unmarried partners are remarkably similar to couples who do not use this term. We find no evidence that researchers should distinguish analytically between newly identified householder unions and unmarried partners. However, until cohabitation measurement is improved in the ACS and other surveys that capture only unmarried partners, researchers should proceed cautiously when using these data sources to study cohabiting families.

Our analysis also demonstrates that subfamily cohabitors differ substantially from unmarried partners. These couples are significantly younger, are less educated, and have lower incomes than unmarried partners. More than 80 % reside with other family members—primarily parents, which offers a living arrangement that substantially improves their standard of living. A clear benefit of the new CPS measures is the ability to identify this small but important subset of cohabiting couples.

The new CPS family relationship variables are essential for studying cohabiting families, which is proving to be an important and growing family form. They correct for a substantial underestimate of cohabitation levels in the United States, allow us to portray the complexity of cohabiting family life, and make possible regular and accurate assessment of the economic well-being of cohabiting couples. Although we focus primarily on cohabitation, our analysis demonstrates the broader value of these new variables. They enable researchers to measure the diversity of married and cohabiting families, distinguishing between families with only shared biological children, only stepchildren, and both shared and stepchildren; these differences may have implications for child well-being (Halpern-Meekin and Tach 2008). In addition, they improve the identification of single-parent families, multigenerational families, and the living arrangements of young adults during transition to adulthood. The new CPS measures represent an important development in the availability of data to accurately measure trends in the living arrangements and economic well-being of Americans over the life course.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this article was presented at the 2009 Population Association of America meetings. We are grateful to Jason Fields, Steve Ruggles, Carolyn Liebler, and anonymous reviewers for helpful comments. Funding was provided by the Minnesota Population Center and by grants from the NSF (SES-0617560) and the NICHD (R01-HD-054643).

Footnotes

A householder is the person in whose name the household unit is owned or rented. When multiple household members meet this requirement, the survey respondent selects one person as the householder.

A usual residence is the place where a person usually lives and sleeps, and can return to at any moment.

Kreider (2008) also compared cohabitation estimates produced by the new CPS measures, the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), and the American Community Survey (ACS).

Nonresident children cannot be identified.

The cohabiting partner locator variable is called PECOHAB and includes unmarried partners and newly identified cohabiting couples. Spouses are identified by A-SPOUSE. PELNMOM and PELNDAD identify mother and father line numbers, and PEMOMTYP and PEDADTYP distinguish between biological, step-, and adoptive parents.

Prior to 2010, the CPS produced a significant underestimate of the prevalence of same-sex unions (Kreider 2008). A change in editing procedures implemented in January 2010 placed CPS estimates in line with those produced using the ACS (Kreider 2010). See Gates (2010) for an evaluation of the measurement of same-sex couples in census data.

We have excluded 11 couples in our sample where there appear to be errors in relationship to householder, the cohabitation pointer, or the parent pointers.

Note that the ASEC collects income data for the previous year. Thus, our estimates of poverty status cover the years 2006–2008.

Documentation is available online (http://cps.ipums.org/cps/repwt.shtml).

Cohabitation levels by sex only reveal the overall earlier union formation of women compared with men.

We measure couple age as the age of the younger partner. Using the ages of male and female partner yielded similar results.

Our analysis excludes 1,057 children residing in a household where there appear to be errors in relationship to householder or pointers.

Contributor Information

S. Kennedy, Minnesota Population Center, University of Minnesota, 50 Willey Hall, 225 19th Ave S., Minneapolis, MN, 55455, USA kenne503@umn.edu

C. Fitch, Minnesota Population Center, University of Minnesota, USA

References

- Carlson Marcia J., Furstenberg Frank F., Jr. The prevalence and correlates of multipartnered fertility among urban US parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:718–732. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Marcia, Sheldon Danziger. Cohabitation and the Measurement of Child Poverty. Review of Income and Wealth. 1999;45:179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Casper Lynne M., Cohen Philip N. How does POSSLQ measure up? Historical estimates of cohabitation. Demography. 2000;37:237–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper Lynne M., Hofferth Sandra L. Playing Catch-up: Improving Data and Measures for Family Research. In: Hofferth Sandra L., Casper Lynne M., editors. Handbook of Measurement Issues in Family Research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fay Robert, Train George. Proceedings of the Section on Government Statistics. American Statistical Association; Alexandria, VA: 1995. Aspects of Survey and Model Based Postcensal Estimation of Income and Poverty Characteristics for States and Counties; pp. 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Fitch Catherine, Goeken Ron, Ruggles Steven. The Rise of Cohabitation in the United States: New Historical Estimates. Minnesota Population Center; Minneapolis: 2005. (Working Paper Series: #2005-03) [Google Scholar]

- Gates Gary. Same sex couples in US Census Bureau Data: Who gets counted and why. Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law; Los Angeles: 2010. Retrieved from http://www.law.ucla.edu/williamsinstitute/pdf/WhoGetsCounted_FORMATTED1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo Karen Benjamin, Furstenberg Frank F., Jr Multipartnered Fertility Among Young Women with a Nonmarital First Birth: Prevalence and Risk Factors. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2007;39:29–38. doi: 10.1363/3902907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Meekin Sarah, Tach Laura. Heterogeneity in two-parent families and adolescent well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:435–451. [Google Scholar]

- Hayford Sarah R., Morgan S. Philip. The quality of retrospective data on cohabitation. Demography. 2008;45:129–141. doi: 10.1353/dem.2008.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iceland John. Measuring Poverty with Different Units of Analysis. In: Hofferth Sandra L., Casper Lynne M., editors. Handbook of Measurement Issues in Family Research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. pp. 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Sheela, Bumpass Larry L. Cohabitation and children’s living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Demographic Research. 2008;19:1663–1692. doi: 10.4054/demres.2008.19.47. article 47. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King Miriam, et al. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current Population Survey. Version 3.0. University of Minnesota; Minneapolis: 2010. [Machine-readable database] [Google Scholar]

- Knab Jean Tansey, McLanahan Sara. Measuring Cohabitation: Does How, When, Who You Ask Matter? In: Hofferth Sandra L., Casper Lynne M., editors. Handbook of Measurement Issues in Family Research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kreider Rose M. Improvements to Demographic Household Data in the Current Population Survey: 2007. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2008. (Housing and Household Economic Statistics Division Working Paper) ( http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps08/twps08.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Kreider Rose M. Increase in Opposite-Sex Cohabiting Couples from 2009 to 2010 in the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) to the Current Population Survey (CPS) U.S. Census Bureau, Housing and Household Economic Statistics Division; Washington, DC: 2010. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/Inc-Opp-sex-2009-to-2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Liebler Carolyn A., Halpern-Manners Andrew. A Practical Approach to Using Multiple-Race Response Data: A Bridging Method for Public-Use Microdata. Demography. 2008;45:143–155. doi: 10.1353/dem.2008.0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning Wendy D., Brown Susan L. Children’s Economic Well-Being in Married and Cohabiting Parent Families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:345–362. [Google Scholar]

- Manning Wendy D., Smock Pamela J. Measuring and Modeling Cohabitation: New Perspectives from Qualitative Data. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005.;67:989–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard Michael S., Harris Kathleen Mullan. Measuring Cohabitation in Add Health. In: Hofferth Sandra L., Casper Lynne M., editors. Handbook of Measurement Issues in Family Research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Teitler Julien O., Reichman Nancy E., Koball Heather. Contemporaneous Versus Retrospective Reports of Cohabitation in the Fragile Families Survey. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2006;68:469–477. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . Poverty Thresholds for 2006 by Size of Family and Number of Related Children Under 18 Years. Housing and Household Economic Statistics Division; Washington, DC: 2006. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/data/threshld/thresh06.html. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . Poverty Thresholds for 2007 by Size of Family and Number of Related Children Under 18 Years. Housing and Household Economic Statistics Division; Washington, DC: 2007. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/data/threshld/thresh07.html. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . Current Population Survey Interviewing Manual: January 2007. 2008a. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/apsd/techdoc/cps/CPS_Interviewing_Manual_July2008rv.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . Poverty Thresholds for 2008 by Size of Family and Number of Related Children Under 18 Years. Housing and Household Economic Statistics Division; Washington, DC: 2008b. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/data/threshld/thresh08.html. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . Poverty Status of Families, by Type of Family, Presence of Related Children, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 1959 to 2008. 2009. Table 4. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/hh-fam/tabMS-2.xls. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . America’s Families and Living Arrangements: 2009. 2010. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hh-fam/cps2009.html. [Google Scholar]