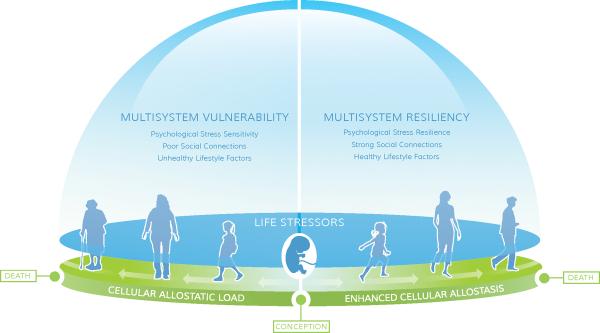

Figure 1.

Lifespan model of stress-induced cell aging as moderated by multisystem resiliency

This lifespan model suggests two divergent trajectories, for simplicity of demonstration. From conception to death, at every stage of development, we are exposed to ubiquitous stressors. The cellular impact of these stressors is partly influenced by genetics/temperament and the severity of the stressors but also by resiliency or vulnerability traits. These traits are largely a result of fetal and childhood development (and genetic dispositions) but can also develop at any time in life, and determine the extent to which cellular allostasis is impacted by subsequent stress exposures. Right panel: Strong stress resiliency traits, social connections, and adherence to healthy behaviors, often shaped by low to manageable stress exposure and secure attachment, provide a positive mutually reinforcing cluster of resiliency factors that shape enhanced cellular allostasis (efficient responding to environmental demands) and good telomere maintenance. This leads to slower organismal aging and longer health span. Left panel: In contrast, high vulnerability to stress reactivity, poor social connections, and difficulty adhering to health behaviors constitute interrelated vulnerability factors that promote cellular allostatic load early in life, and accelerated telomere shortening. This profile can start at early in life, where early exposure to severe stress, and insecure attachment, may promote neural networks primed for exaggerated vulnerability to stress reactivity, limiting development of resiliency factors. This profile of impoverished resiliency leads to rapid organismal aging and early frailty and disease.