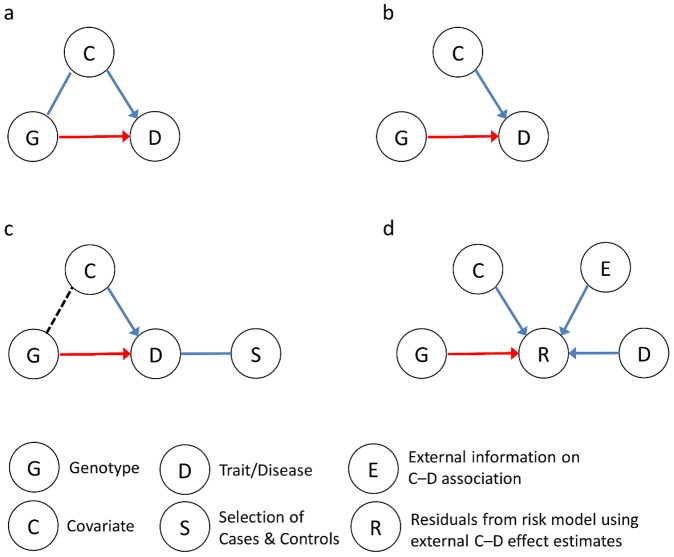

Figure 1. Impact of—and approaches to—including covariates in the analysis of gene–trait associations.

(a) The covariate C is a confounder associated with both the trait D and the gene G but is not an intermediate on the causal path of interest between G and D. The G–D association should be assessed while controlling C. Omitting C from the analysis of the G–D association can lead to misattribution of a C–D effect to G and false discovery or biased estimates of a G–D effect. (b) The covariate C is independently associated with the trait D but not with gene G (so C is not a confounder). If the trait is quantitative or the study subjects are randomly ascertained, including C in a linear or logistic regression model will increase power to detect the G–D association. (c) If the trait is binary and the subjects are ascertained based on case-control status, the probability of selection (S) depends on G and C and induces a correlation between them. Then including C in a logistic regression model can inflate the G–D association's standard error, reducing power. Omitting C provides the most potential gain in power when C has a strong effect on D, and when D is less common [1]. (d) In Zaitlen et al.'s new approach [6] for evaluating G–D associations with case-control data, a risk model for D is developed from external information about the C–D association and observed C and D levels. Residuals from this model, R, distinguish high- and low-risk cases and controls. Then testing for G–R associations assesses genetic effects unexplained by C in a potentially more powerful manner than conventional logistic regression.