Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is defined by the degeneration of nigral dopaminergic (DA) neurons and can be caused by monogenic mutations of genes such as parkin. The lack of phenotype in parkin knockout mice suggests that human nigral DA neurons have unique vulnerabilities. Through the generation and analyses of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from normal subjects and PD patients with parkin mutations, we show here that loss of parkin in human midbrain DA neurons greatly increased the transcription of monoamine oxidases and oxidative stress, significantly reduced DA uptake and increased spontaneous DA release. Lentiviral expression of parkin, but not its PD-linked mutant, rescued all the phenotypes. The results suggest that parkin controls dopamine utilization in human midbrain DA neurons by enhancing the precision of dopaminergic neurotransmission and suppressing dopamine oxidation. Thus, the study provides novel targets and a physiologically relevant screening platform for disease-modifying therapies of PD.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is clinically defined by a core set of motor symptoms that are believed to be caused by the degeneration of dopaminergic (DA) neurons in substantia nigra1. A variety of environmental and genetic factors underlie the accelerated degeneration of nigral DA neurons in PD2. Although monogenic forms of Parkinson’s disease account for a small percentage of cases2, understanding how mutations of these genes lead to the selective degeneration of nigral DA neurons holds great promise to the discovery of disease-modifying therapies for PD. Among the genes that have been causatively linked to Parkinson’s disease, parkin is unique in that its mutations are most frequently found in recessively inherited PD cases; they are completely penetrant and do not have a founder effect3. Parkin is a ubiquitin-protein ligase4 for a variety of substrates5. In sharp contrast to the situation seen in PD patients with parkin mutations6, parkin knockout mice do not exhibit any robust phenotype7, suggesting that parkin mutations selectively impact on human nigral DA neurons.

One of the major roadblocks in PD research is the lack of live human midbrain dopaminergic neurons. The discovery of human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)8,9 allowed us to generate patient-specific iPSCs, which were differentiated in vitro to midbrain dopaminergic neurons for mechanistic studies of parkin. We found that parkin mutations in iPSC-derived human midbrain DA neurons significantly elevated oxidative stress induced by dopamine oxidation because the transcription of monoamine oxidases A and B was greatly increased. Specific dopamine uptake through dopamine transporter (DAT) was significantly decreased, as the amounts of DAT-binding sites were significantly reduced. In addition, spontaneous, Ca2+-independent release of dopamine was significantly increased while activity- and Ca2+-dependent DA release remained the same. These dopamine-specific phenotypes were significantly reversed by lentiviral expression of wild-type parkin, but not its PD-linked T240R mutant or GFP. The results not only reveal mechanistic insights into the cellular functions of parkin in human midbrain DA neurons – the cell type selectively impacted by its mutations, they also provide novel targets and a screening platform for the discovery of disease-modifying agents that can mimic the protective functions of parkin.

Results

Generation of iPSCs from PD patients with parkin mutations

To understand why mutations of parkin cause the selective degeneration of human nigral DA neurons and ensuing Parkinson’s disease6, we generated iPSCs using dermal fibroblasts from two PD patients with parkin mutations (one with compound heterozygous deletions of exon 3 and exon 5, designated as P001; the other with homozygous deletion of exon 3, designated as P002) and two control subjects (designated as C001 and C002) who are unrelated, unaffected spouses of idiopathic PD patients. Dermal fibroblasts cultured from skin punch biopsy were reprogrammed to iPSCs using lentiviruses expressing human Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc and Nanog10. Multiple clones with human embryonic stem cell (hESC) morphology were picked for each of the four subjects. After expansion and initial characterization, one representative clone for each subject (C001#2, C002#1, P001#3, P002#4.5) was used for detailed studies. As shown in Fig. 1 for P002 iPSC and Supplementary Fig. S1 for the other three lines, all four lines of iPSCs exhibited morphology indistinguishable from hESCs such as H9 and can be maintained indefinitely on MEF feeders or matrigel. Pluripotency markers such as alkaline phosphatase (AP), Oct4, Nanog, SSEA3, SSEA4, Tra-1-60 and Tra-1-81 were strongly expressed in all four lines. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) showed that a panel of endogenous pluripotency genes (except NODAL) were expressed at levels comparable to those in H9 hESC (Fig. 1i and Supplementary Fig. S1y). Sequences of PCR primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The reason for the low level of NODAL is unclear and might be related to our iPSC-derivation method and condition (e.g. we used 5% O2 in iPSC derivation and culture). DNA methylation in the promoter regions of Oct4, Nanog and Sox2 was greatly reduced in the four lines of iPSCs, in comparison to that in the original fibroblast lines (Supplementary Fig. S2). The promoter sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S2. The five viral transgenes were strongly silenced in these iPSCs (Fig. 1j and Supplementary Fig. S1y). RT-PCR was performed on total RNA from the four lines of iPSCs grown on matrigel to confirm parkin mutations in the two PD patients (Fig. 1k). The RT-PCR products were sequenced to verify that P001 iPSC indeed had compound heterozygous deletions of exon 3 and exon 5 while P002 iPSC had homozygous deletion of exon 3 (Fig. 1l, m). Western blotting of total cell lysates from the four lines of iPSCs confirmed that parkin was not expressed in P001 and P002 cells (Fig. 1n). In embryoid body-mediated spontaneous differentiation assays, all four lines of iPSCs could be differentiated to cells of the three germ layers (Fig. 1o–q for P002 and Supplementary Fig. S3 for the other three lines). They also formed teratomas under kidney capsules in SCID mice (Fig. 1r–t for P002 and Supplementary Fig. S3 for the other three lines). All four lines of iPSCs showed normal karyotypes (Supplementary Fig. S4). This was confirmed by array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH), which showed no significant chromosomal change in the iPSCs when compared to pooled normal human genomic DNA (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Figure 1. Generation of iPSCs from normal subjects and PD patients with parkin mutations.

(a–h) Phase contrast image (a) of P002 iPSCs from a PD patient with parkin mutations and staining of the line with pluripotency markers alkaline phosphatase (AP) (b), Oct4 (c), Nanog (d), SSEA3 (e), SSEA4 (f), Tra-1-60 (g), Tra-1-81 (h). Bar, 100 μm. (i) Expression levels of endogenous pluripotency genes in the four representative iPSC lines and H9 hESC. (j) Levels of viral transgenes and their endogenous counterparts in the four iPSC lines and H9 hESC. Error bars in (i) and (j) represent s.e.m., n=9. (k–m) RT-PCR amplification of the parkin transcripts in the four iPSC lines (k) and sequencing results of the band with exon 3 deletion (l) and the band with exon 5 deletion (m). (n) parkin immunoblot of total cell lysates from the four lines of iPSCs. (o–q) EB-mediated spontaneous differentiation of P002 iPSCs in vitro. Bar, 10 μm. (r–t) Teratoma formation assay for P002 iPSCs. endo, endoderm; meso, mesoderm; ecto, ectoderm; Sm, smooth. Bar, 10 μm.

Differentiation of iPSCs to midbrain DA neurons

We used a feeder-free, chemically defined, directed differentiation protocol11 to differentiate the four lines of iPSCs to midbrain DA neurons in vitro (Fig. 2). The iPSC colonies dissociated from MEF cells were first cultured as floating cell aggregates (EB) for 4 days in hESC medium with 10 μM SB431542 to enhance neural differentiation12. After the cell aggregates were cultured in suspension in the presence of 20 ng/ml bFGF for two more days, they were plated on laminin-coated surface. Many colonies had an elongated columnar morphology. These primitive neuroepithelial cells were differentiated to definitive neuroepithelia in the presence of FGF8a (20 ng/ml) and SHH (100 ng/ml). Multiple neural tube-like rosettes were seen in the center of the colony (Fig. 2b). The rosettes were peeled off from the flat peripheral cells and cultured in suspension in the presence of FGF8a (50 ng/ml) and SHH (100 ng/ml), B27 supplements (1×) and ascorbic acid (200 μM) to form neurospheres that were patterned to a mid/hind brain destiny (Fig. 2c). Around day 24, the neurospheres were dissociated and plated on 6-well plates or cover slips precoated with polyornithine, laminin and matrigel. We found that the addition of matrigel coating significantly inhibited the formation of cell aggregates during the last step of differentiation and might have contributed to the improved dopaminergic characteristics such as specific dopamine uptake. Trophic factors such as BDGF (20ng/ml) and GDNF (20ng/ml) were used to generate mature dopaminergic neurons, which were seen around 70 days from the start of differentiation (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2. Directed differentiation of the iPSCs to midbrain dopaminergic neurons in vitro.

(a–d) iPSCs were differentiated with the protocol in (a) to neuroepithelia (b), neurosphere (c) and neurons (d). Bars, 100 μm in (b) and (c), 10 μm in (d).

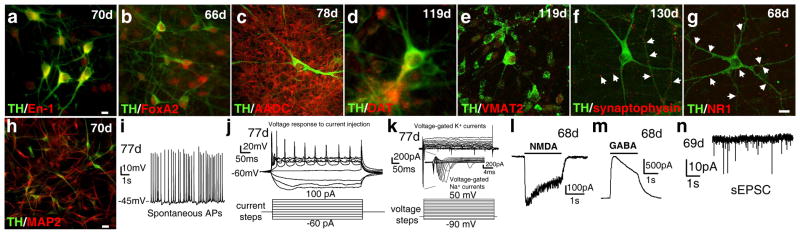

P002 iPSC-derived neuronal cultures contained TH+ neurons with complex morphology and in clusters (e.g. Fig. 3a–b). These TH+ neurons expressed the midbrain markers engrailed-1 (En-1)13 (Fig. 3a) and FoxA2 (Fig. 3b), as well as other dopaminergic markers such as AADC (Fig. 3c), DAT (Fig. 3d), VMAT2 (Fig. 3e), suggesting that they are midbrain DA neurons. They expressed synaptic markers such as synaptophysin (Fig. 3f) and NR1 (Fig. 3g) and markers for mature neurons such as MAP2 (Fig. 3h). Similar expression of these markers was seen in neuronal cultures derived from C001, C002 and P001 iPSC lines (Supplementary Fig. S6). Consistent with this, RT-PCR experiments showed that TH, En-1, AADC, DAT, VMAT2, Nurr1, Ptx3, FoxA2, Lmx1b were strongly expressed in iPSC-derived neurons, but not in the iPSCs (Supplementary Fig. S7). The weak expression of FoxA2 and Lmx1b in our iPSCs was similar to what has been reported before14,15. qRT-PCR experiments showed that there were very low levels of viral transgene expression in the four lines of iPSC-derived neurons (Supplementary Fig. S8). Similar to what has been reported recently for the differentiation of iPSCs to motor neurons16, the low level of transgene expression in our iPSC-derived neurons did not appear to affect the differentiation or function of these neurons, as electrophysiological studies showed that P002 neurons fired spontaneous action potentials (Fig. 3i) and evoked action potentials (Fig. 3j). They have voltage-gated K+ currents and voltage-gated Na+ currents (Fig. 3k), NMDA-gated currents (Fig. 3l), GABA-gated currents (Fig. 3m), and spontaneous Excitatory Postsynaptic Currents (EPSCs) (Fig. 3n). Similar electrophysiological profiles were observed in neurons derived from C001, C002 and P001 iPSCs (Supplementary Fig. S9). These results showed that all four lines of iPSC-derived neuronal cultures had synaptic transmission and contained midbrain dopaminergic neurons.

Figure 3. Properties of the iPSC-derived midbrain dopaminergic neurons.

(a–h) P002 iPSC-derived neuronal cultures were co-stained for TH and the midbrain markers engrailed-1 (En-1) (a) and FoxA2 (b), the dopaminergic markers AADC (c), DAT (d) and VMAT2 (e), the synaptic markers synaptophysin (f) and NR1 (g), and the marker for mature neurons MAP2 (h). Bars, 10 μm. (i–n) These neurons fired spontaneous APs (i) and evoked APs (j), had voltage-gated K+ and Na+ currents (k), NMDA-gated currents (l), GABA-gated currents (m) and spontaneous EPSC (n). Dates (e.g. 70d) indicated were from the start of differentiation. AP, action potential; sEPSC, spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents.

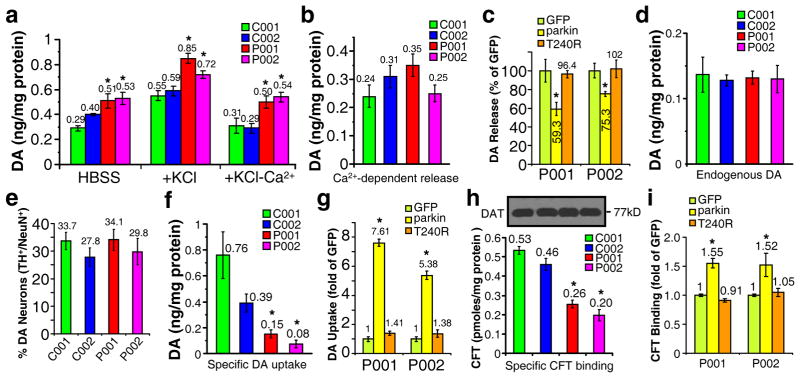

Parkin mutations increased spontaneous DA release

To demonstrate that these midbrain DA neurons are functional, we measured spontaneous and activity-dependent dopamine release by reverse-phase HPLC coupled with electrochemical detection of dopamine17. The iPSC-derived neuronal cultures were incubated at 37°C in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), HBSS with 56 mM KCl, or Ca2+-free HBSS with 56 mM KCl. Spontaneous DA release in HBSS (30 min) was robustly observed in all four lines of iPSC-derived DA neurons and was significantly increased in P001 and P002, compared to C001 or C002 (p<0.05, n=3–8, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed) (Fig. 4a). DA release was markedly increased by KCl-induced membrane depolarization in the four lines of DA neurons, and the increases were abolished when Ca2+-free HBSS was used with KCl (Fig. 4a). Ca2+- and activity-dependent release was calculated by the difference between KCl-induced DA release in the presence and absence of Ca2+; it was not significantly different among the four lines of DA neurons (Fig. 4b). To ascertain that increased spontaneous DA release was indeed caused by the loss of parkin, we infected P001 or P002 neurons with lentivirus expressing GFP or FLAG-tagged parkin or its PD-linked T240R mutant. Overexpression of wild-type parkin, but not its T240R mutant or GFP, significantly reduced spontaneous DA release in HBSS from P001 or P002 neurons (p<0.05 vs. P001 or P002 expressing GFP, respectively, n=4, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed) (Fig. 4c). The spontaneous dopamine release was not significantly affected by selective inhibitors of dopamine transporter (DAT) such as GBR12909 (10 μM) or nomifensine (10 μM) (Supplemental Fig. S10a), suggesting that it is not caused by dopamine efflux through DAT. Total dopamine content in these neuronal cultures as measured by HPLC was not significantly different (Fig. 4d). We counted more than 1000 NeuN+ neurons for each line. The percentage of TH+ neurons in NeuN+ neurons was not significantly different (Fig. 4e). We plated the same number of neuroepithelial cells at the last step of differentiation. The total number of neurons were too numerous to count. Thus, the similar percentages of TH+ neurons suggest that the numbers of dopaminergic neurons are similar across the four lines.

Figure 4. Dopamine release and uptake in the four lines of iPSC-derived midbrain DA neurons.

(a) Dopamine release in HBSS, or in HBSS plus KCl (56 mM), or Ca2+-free HBSS plus KCl (56 mM) from normal and parkin-deficient iPSC-derived midbrain neuronal cultures. *, p<0.05 vs. C001 or C002 in the same condition, n=3–8, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed. (b) Ca2+-dependent DA release was calculated from KCl-induced DA release in the presence or absence of Ca2+. (c) Spontaneous DA release in HBSS from P001 or P002 neurons infected with lentivirus expressing GFP, parkin, or T240R mutant parkin. *, p<0.05 vs. P001 or P002 expressing GFP, respectively, n=4, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed. (d, e) The amount of endogenous dopamine (d) and the percentage of TH+ neurons in NeuN+ neurons (e) in the four lines of iPSC-derived neuronal cultures. At least 1000 NeuN+ neurons were counted for each line of iPSC-derived neurons. (f) Specific dopamine uptake in the four lines of iPSC-derived midbrain neuronal cultures. *, p<0.05 vs. C001 or C002, n=5–9, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed. (g) Specific DA uptake in P001 or P002 neurons infected with lentivirus expressing GFP, parkin, or T240R mutant parkin. *, p<0.05 vs. P001 or P002 expressing GFP, respectively, n=4, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed. (h) Specific [3H]CFT-binding on dopamine transporter in the four lines of iPSC-derived midbrain neuronal cultures. *, p<0.05 vs. C001 or C002, n=6, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed. (i) Specific [3H]CFT-binding in P001 or P002 neurons infected with lentivirus expressing GFP, parkin, or T240R mutant parkin. *, p<0.05 vs. P001 or P002 expressing GFP, respectively, n=5, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed.

Parkin mutations decreased DA uptake and DAT-binding sites

We measured specific DA uptake by incubating the neuronal cultures for 10 min at 37°C with 5 μM dopamine in the absence or presence of 10 μM nomifensine, a selective inhibitor of dopamine transporter (DAT). The condition was based on the dose response and time course of dopamine uptake in C001 neurons (Supplementary Fig. S10b, c). The ligand concentration (5 μM) was very close to Vmax condition and the duration (10 min) was in the linear phase of uptake. It was used before in our previous study18 and was consistent with other studies using cloned human DAT in exogenous expression systems19,20. The amounts of dopamine in the cells as measured by HPLC were used to calculate specific DA uptake, which is the difference of DA uptake in the absence and presence of nomifensine. Non-specific DA uptake in the presence of nomifensine was not significantly different between the four lines of iPSC-derived neurons (data not shown). Furthermore, dopamine uptake was not significantly affected by nisoxetine (0.1 μM), a selective inhibitor of norepinephrine transporter (Supplemental Fig. S10d). As shown in Fig. 4f, specific DA uptake was significantly diminished in P001 and P002 DA neurons, compared to C001 or C002 DA neurons (p<0.05, n=5–9, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed). Lentiviral expression of parkin, but not its T240R mutant or GFP, significantly rescued the effect (p<0.05 vs. P001 or P002 expressing GFP, respectively, n=4, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed) (Fig. 4g), suggesting that the effect is indeed caused by loss-of-function mutations of parkin in P001 and P002 neurons.

Our previous study has shown that parkin enhances the cell surface expression of DAT by ubiquitinating and degrading misfolded DAT to facilitate the oligomerization of native DAT conformers in the endoplasmic reticulum18, a prerequisite for the plasma membrane delivery of this misfolding-prone protein21. To test whether reduced dopamine uptake in P001 and P002 neurons is caused by decreased amount of correctly folded DAT that are competent for selective dopamine uptake, we measured the amounts of DAT-binding sites using [3H]CFT [2-β-carbomethoxy-3-beta-(4-fluorophenyl)-tropane]18, a potent cocaine analog that specifically binds to DAT. The iPSC-derived neuronal cultures were incubated for 2 hr at 4°C in binding buffer with 4 nM [3H]CFT in the absence or presence of the selective DAT inhibitor GBR12909 (10 μM). Total cell lysates, in which [3H]CFT was bound to correctly folded DAT molecules, were measured in a scintillation counter to calculate specific [3H]CFT-binding on DAT (the difference in binding with or without GBR12909). As shown in Fig. 4h, specific [3H]CFT-binding was greatly reduced in P001 and P002 DA neurons, compared to that C001 or C002 DA neurons (p<0.05, n=6, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed), while the levels of total DAT in whole cell lysates were very similar. To confirm that reduced DAT-binding sites were indeed caused by parkin mutations in P001 and P002 neurons, we infected these neurons with lentivirus expressing GFP, parkin or its PD-linked T240R mutant. As shown in Fig. 4i, overexpression of parkin, but not T240R or GFP, significantly increased the specific binding of [3H]CFT in P001 or P002 neurons (p<0.05 vs. P001 or P002 expressing GFP, respectively, n=5, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed).

Parkin mutations elevated ROS by increasing MAO transcripts

To test the impact of parkin mutations on dopamine-induced oxidative stress, which plays a key role in the selective degeneration of nigral DA neurons in PD22, we treated the four lines of iPSC-derived neuronal cultures without or with 75 μM dopamine for 4 hrs and examined the level of oxidative stress by measuring the amounts of protein carbonyls in the total cell lysates. Without dopamine treatment, very few protein carbonyls were seen in all four lines of human neurons. After DA treatment, the amounts of protein carbonyls were greatly increased in P001 and P002 neurons, compared to those in C001 or C002 neurons (p<0.01, n=8, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed), which only had very modest increases over their basal levels (Fig. 5a,b). The results suggest that dopamine-induced oxidative stress is markedly elevated when parkin is mutated. Our previous study has shown that parkin suppresses the transcription of monoamine oxidases (MAO) A and B17, which are mitochondrial enzymes responsible for the oxidative deamination of dopamine, a reaction that produces large quantities of reactive oxygen species23. When we measured the mRNA levels of MAO-A and MAO-B by qRT-PCR, we found that the amounts of MAO-A and MAO-B transcripts were significantly increased in P001 and P002 neurons, compared to those in C001 or C002 neurons (p<0.01, n=9, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed) (Fig. 5c). To substantiate these findings, we measured the activities of MAO-A or MAO-B in total cell lysates from these neurons using [14C]tyramine as a substrate and pargyline or clorgyline to inhibit MAO-B or MAO-A, respectively17. As shown in Fig. 5d, the amounts of MAO-A or MAO-B enzymatic activities were significantly increased in P001 and P002 neurons, compared to those in C001 or C002 neurons (p<0.01, n=6–11, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed).

Figure 5. Oxidative stress and MAO transcription in the four lines of iPSC-derived neurons.

(a, b) Western blot analysis (a) and quantification (b) of protein carbonyls in the four lines of iPSC-derived neurons treated without or with dopamine (75μM for 4 hr). DNP, 2,4-dinitrophenyl; p150, p150glued, a dynactin subunit as loading control. *, p<0.01 vs. C001 or C002 with DA treatment, n=8, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed. (c) qRT-PCR measurement of MAO-A and MAO-B transcripts in the four lines of iPSC-derived neuronal cultures. *, p<0.01 vs. C001 or C002, n=9, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed. (d) MAO-A and MAO-B activities in the four lines of iPSC-derived neurons. *, p<0.01 vs. C001 or C002, n=6–11, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed. (e, f) qRT-PCR measurements of MAO-A and MAO-B mRNA levels in P001 (e) or P002 (f) neurons infected with lentivirus expressing GFP, parkin or T240R mutant parkin. (g–h) MAO-A and MAO-B activities in P001 (g) or P002 (h) neurons infected with lentivirus expressing GFP, parkin or T240R mutant parkin. (i–k) Western blot analysis (i) and quantification (k) of protein carbonyls in P001 or P002 neurons infected with lentivirus expressing GFP, parkin or T240R mutant parkin. Total cell lysates were blotted with antibodies against GFP or FLAG or p150glued (j). *, p<0.05 vs. GFP-expressing neurons, n=3–4 for (e) to (k), student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed. mg, milligrams of total cellular proteins.

To ascertain that these phenotypes were indeed caused by parkin mutations, we infected P001 or P002 neurons with lentivirus expressing GFP, FLAG-tagged parkin or T240R mutant parkin. Overexpression of parkin, but not its PD-linked T240R mutant or GFP, significantly lowered the mRNA levels of MAO-A and MAO-B in P001 and P002 neurons (p<0.05, n=4, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed) (Fig. 5e, f), as well as the activities of MAO-A and MAO-B in total cell lysates from these neurons (p<0.05, n=4, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed) (Fig. 5g, h). Consistent with these, the amounts of protein carbonyls in P001 and P002 neurons were significantly decreased by overexpression of parkin, but not its T240R mutant or GFP (p<0.05, n=3, student’s t-test, unpaired, two tailed) (Fig. 5i, k). The expression levels of GFP, FLAG-tagged parkin or its T240R mutant, and p150glued (as loading control) were shown in Fig. 5j.

Parkin mutations did not significantly affect mitochondria

We examined whether the loss of parkin significantly affect mitochondria by treating the four lines of iPSC-derived neurons without or with CCCP (10 μM for 16 hr) to induce mitophagy24. There was no significant change in the amount of mitochondria as reflected in the quantitative PCR measurement of mitochondria DNA against the nuclear gene actin (Fig. 6a–c). The protein expression levels of PINK1 and DJ-1 in the presence or absence of CCCP (10 μM for 24 hr) were not significantly changed (Fig. 6d). The expression levels of α-synuclein were also very similar among the four lines of iPSC-derived neurons (Fig. 6e).

Figure 6. Mitochondrial DNA levels and expression levels of PINK1, DJ-1 and α-synuclein in the four lines of iPSC-derived neurons.

(a–c) Quantitative PCR measurement of three different segments of mitochondria DNA against the nuclear gene actin in the four lines of iPSC-derived neurons treated with or without CCCP (10 μM for 16 hr). mtDNA3130-3301 is a region not transcribed and has no homology with mitochondrial pseudogenes in the nuclear genome. (d) Protein expression levels of PINK1 and DJ-1 in the absence or presence of CCCP treatment (10 μM for 24 hr). PINK1 has two bands, uncleaved at 63 kDa and cleaved at 52 KDa. (e) The expression level of α-synuclein in the four lines of iPSC-derived neurons.

Discussion

One of the critical challenges for Parkinson’s disease research is the lack of live human nigral DA neurons for mechanistic studies and drug discovery, as animal models of Parkinson’s disease generally do not recapitulate the human condition very well25. The discovery of human induced pluripotent stem cells8,9 makes it possible to generate patient-specific midbrain DA neurons to study their unique vulnerabilities in Parkinson’s disease, particularly in monogenic forms of PD, in which the mechanistic link between genotype and phenotype is being vigorously pursued. The present study showed that parkin mutations directly impinge on dopamine utilization in human midbrain DA neurons.

The loss of parkin significantly increased the spontaneous DA release that was independent of extracellular [Ca2+] (Fig. 4a), but did not significantly affect Ca2+-dependent DA release triggered by membrane depolarization (Fig. 4b). It suggests that parkin limits somatodendritic DA release, which can be independent of extracellular [Ca2+]26,27. Since parkin is involved in vesicle trafficking through monoubiquitination of proteins such as Eps1528, it seems plausible that parkin may affect the recycling of dopamine-containing vesicles that are involved in somatodendritic release. There is a strong feedback mechanism on the activity of TH, the rating limiting enzyme in the synthesis of dopamine. It serves to maintain the homeostasis of dopamine between cytosolic and vesicular pool so that increased release may be compensated by increased synthesis. In addition, VMAT2, DAT, MAO, COMT also impact on the homeostasis of dopamine29. Thus, the total amount of endogenous dopamine was not significantly affected by parkin mutations (Fig. 4d).

On the other hand, loss of parkin significantly decreased dopamine uptake (Fig. 4f) by reducing the total amount of correctly folded DAT (Fig. 4h). This is consistent with our previous finding that parkin increases the cell surface expression of DAT by ubiquitinating and degrading misfolded DAT conformers to enhance oligomerization of native DAT conformers in the ER and their subsequent delivery to the plasma membrane18. Recent PET studies have shown that 18F-DOPA uptake is significantly reduced in PD patients with parkin mutations, compared to controls30,31. Thus, mutations of parkin significantly disrupt the spatial and temporal precision of dopaminergic neurotransmission by increasing spontaneous DA release and decreasing DA uptake. The net outcome is increased extracellular DA level, which was mimicked by the dopamine treatment experiment in Fig. 5a. In this paradigm, parkin mutations greatly increased dopamine-induced oxidative stress (Fig. 5a,b) because mutant parkin lost the ability to suppress MAO transcription (Fig. 5c). This result is consistent with our previous finding that parkin suppresses the transcription of monoamine oxidase A and B17. It appears that P002 had a particularly high level of MAO-B transcript (Fig. 5c) and activity (Fig. 5d), even when compared to P001. This might be related to different genetic background of the two patients and/or different parkin mutations that they carry (P002 has homozygous exon 3 deletion, while P001 has compound heterozygous deletion of exon 3 and exon 5). Overexpression of parkin, but not its PD-linked T240R mutant or GFP, rescued all the phenotypes – increased spontaneous DA release, decreased DA uptake and DAT-binding sites, increased MAO transcription and DA-induced oxidative stress (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). Thus, these dopamine-specific phenotypes are indeed caused by loss-of-function mutations of parkin.

Our findings on dopamine-specific functions of parkin also shed light on novel therapeutic targets of PD. Recent studies have shown that MAO-B inhibitors have a significant, albeit modest, effort in slowing down the progression of Parkinson’s disease32. Since parkin suppresses MAO transcription by ubiquitinating and degrading estrogen-related receptors33, it may be more advantageous to mimic the protective function of parkin by suppressing MAO transcription using inhibitors of estrogen-related receptors (e.g. XCT-790)34, rather than inactivating MAO activity indiscriminately with suicide substrates such as those used in the current therapy. Alternatively, the ability of parkin to repress p5335 could also be exploited to achieve similar effects. On the other hand, agents that could enhance the folding of native DAT conformers or the elimination of misfolded DAT conformers may be good candidates to substitute parkin in restoring dopamine uptake. Agents that directly enhance DA uptake or increase the cell surface expression of DAT may also be suitable drug candidates.

In conclusion, the study has discovered how mutations of parkin disrupt an essential function of human midbrain dopaminergic neurons – the coordinated utilization of dopamine as a neurotransmitter and the control of dopamine toxicity. Mechanistic insights gained from the study would be very useful for the development of disease-modifying therapies of Parkinson’s disease on a platform that closely resembles human nigral DA neurons in vivo. Further studies are needed to address why nigral dopaminergic neurons, in comparison to other types of dopaminergic neurons, are particularly vulnerable in Parkinson’s disease and how parkin protects against these vulnerabilities.

Methods

Derivation of iPSCs from skin fibroblasts

With approvals from the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board of the State University of New York at Buffalo and the Ethics Committee of Tottori University Faculty of Medicine, we obtained informed consents from research subjects participating in this study. Skin punch biopsies (5 mm in diameter or less) were obtained from two PD patients with parkin mutations and two control subjects. Skin fibroblasts (1×105) at passage 2 or 3 were infected for 16 hr with the following FUW-tetO-LoxP lentiviruses: hOct4, hSox4, hKlf4 and hNanog each at MOI 15, c-Myc at MOI 6, and M2rtTA at MOI 30 in the presence of 4 μg/ml polybrene10. Doxycycline (1 μg/ml) was added for at least 10 days and later at 0.5 μg/ml until hESC-like clones appeared. VPA (0.5 or 1 mM) was added for 7 days with DOX in the beginning. Clones with hESC morphology appeared between day 24 and 40. They were picked and expanded under hESC culture condition. The proviruses integrated in the genomes of the four iPSC lines were not removed because a recent study has demonstrated that neural differentiation of various iPSCs is not affected by the absence or presence of proviruses introduced during reprogramming36.

Characterization of iPSCs

The iPS cells were stained with SSEA-3 (1:1000, Millipore), SSEA-4 (1:1000, Millipore), TRA-1-60 (1:1000, Millipore), TRA-1-81(1:1000, Millipore), Oct4 (1:1000, Millipore), Nanog (1:500, Millipore). Alkaline phosphatase activity was detected using an alkaline phosphatase detection kit (Millipore). To confirm parkin mutations in iPS cells, RT-PCR was performed on total RNA isolated from iPSCs grown on matrigel. The cDNA region spanning exons 2–6 was amplified using two primers CACCTACCCAGTGACCATGATA and GCTACTGGTGTTTCCTTGTCAGA. The PCR products were sequenced. DNA methylation states of the promoters of endogenous Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog were analyzed using the Sequenom MassARRAY EpiTyper at Roswell Park Cancer Institute (PRCI) Genomics Shared Resource. Karyotyping of iPSCs grown on matrigel was performed by RPCI Sky Core Facility using Giemsa staining of iPSCs mitotically arrested at metaphase with colcimid. Chromosomes from at least 30 metaphase cells were analyzed. Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH) of iPSCs was performed by the RPCI Genomics Shared Resource using commercially available, sex-mismatched pooled genomic DNA. One million iPSCs mixed with collagen at a 1:1 ratio were aliquoted to ~10μl pellets, which were grafted under the renal capsule of each kidney in a SCID mouse (C.B-Igh-1bIcrTac-Prkdcscid/Ros). Large tumors (~1 cm in size) were found for each iPSC line 2–3 months after grafting. All animal work for the teratoma formation assay was performed by RPCI Mouse Tumor Model Resource following RPCI IACUC approved protocol.

Directed Differentiation of iPSCs to midbrain DA neurons

The iPSCs were differentiated to midbrain DA neurons in a directed differentiation protocol37 with two improvements. First, SB431542 (10 μM) was used for the first four days of iPSC floating aggregates culture to enhance neural differentiation38. Second, matrigel was used in addition to polyornithine and laminin to coat the cell culture surface at the last step of differentiation (from neurosphere to neurons). Mature midbrain DA neurons capable of specific dopamine uptake were generated around day 70 from the start of differentiation.

Dopamine Release

The iPSC-derived neuronal cultures differentiated at the same conditions in 6-well plates were treated at 37°C in the following way for each set of three wells (a, b, c). Well (a) was incubated in 1 ml Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) for 30 min. Well (b) was incubated in 1 ml HBSS for 15 min and then 56 mM KCl was added for another 15 min. Well (c) was incubated in 1 ml HBSS without Ca2+ and without Mg2+, but with 2 mM EDTA for 15 min and then 56 mM KCl was added for another 15 min. The 1 ml HBSS solutions were taken out from the wells. GSH and EGTA were added to the solutions to the final concentration of 2 mM to prevent auto-oxidation of dopamine. The amounts of DA in HBSS solutions were measured by reverse phase HPLC (ESA Model 582 with ESA MD150×3.2 column, at 0.6 ml/min flow rate in MD-TM mobile phase) coupled with electrochemical detection17 (ESA Coulochem III, E1: −250 mV, 2 μA; E2: 350 mV, 2 μA). Cells in the three wells were lysed in 0.5 N NaOH to measure protein levels, which were used to normalize dopamine release. Spontaneous dopamine release is reflected in (a), while Ca2+- and activity-dependent release is reflected in (b)–(c).

Specific Dopamine Uptake

The iPSC-derived neuronal cultures in 6-well plates were rinsed with 1 ml prewarmed uptake buffer (10 mM HEPES, 130 mM NaCl, 1.3 mM KCl, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM glucose, pH 7.4) three times. Cells were incubated for 10 min at 37°C with 1 ml uptake buffer containing 5 μM dopamine without or with 10 μM nomifensine (a selective inhibitor of dopamine transporter). After the cells were washed at least three times in uptake buffer, they were lysed in 0.1 M perchloric acid with 1 mM EDTA and 0.1 mM sodium bisulfite. Cleared cell lysates were analyzed for dopamine on HPLC coupled with electrochemical detection17 (E1: −150 mV, 2 μA; E2: 220 mV, 2 μA). The pellets of cellular proteins were dissolved in 1 ml 0.5N NaOH to measure protein contents, which were used to normalize dopamine uptake. Specific dopamine uptake is reflected in the difference of DA content in the absence and presence of the DAT inhibitor nomifensine. The amount of dopamine in the iPSC-derived neuronal cultures without any treatment was also measured.

[3H]CFT Binding Assay

DAT radioligand binding assay using [3H]CFT was performed with a protocol similar to what was described before18. After iPSC-derived neuronal cultures in 6-well plates were washed three times at room temperature in binding buffer (10 mM Phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 0.32M sucrose), they were incubated in 1 ml of binding buffer containing 4 nM [3H]CFT without or with the selective DAT inhibitor GBR12909 (10 μM) for 2 hr at 4°C. The assay was terminated by three washes with 1 ml of ice-cold binding buffer. The neuronal cultures were lysed in 0.5 ml of 1% SDS for 15 min at room temperature and the entire lysate was measured in a scintillation counter. Nonspecific binding was defined as binding in the presence of 10 μM GBR12909. It was subtracted from total binding to derive specific [3H]CFT binding. The total amounts of cellular proteins were measured in parallel experiments and used to normalize specific [3H]CFT binding.

Measurement of protein carbonyls

The levels of protein carbonyls were measured as described before39. Protein carbonyls in total cell lysates containing 80 μg proteins were measured with the Oxyblot protein oxidation detection kit (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Intensities of DNP-modified proteins were quantified by densitometry. Background-subtracted signals were normalized against untreated C001 neural cultures.

Electrophysiology

Recordings of synaptic and ionic currents used standard whole-cell voltage-clamp techniques40. For the recording of spontaneous EPSC (sEPSC), membrane potential was held at −70 mV. The external solution contained (mM): 127 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 12 glucose, 10 HEPES, pH 7.3–7.4, 300–305 mOsm/l. To isolate AMPAR-mediated response, the NMDA receptor antagonist D-aminophosphonovalerate (APV, 20 μM) and GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline (10 μM) were added. The internal solution consisted of the following (in mM): 130 Cs methanesulfonate, 10 CsCl, 4 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 2.2 QX-314, 12 phosphocreatine, 5 MgATP, 0.5 Na2GTP, and 0.1 leupeptin, pH 7.2–7.3, 265–270 mOsm. For the recording of NMDA-gated and GABA-gated currents, membrane potential was held at −60 mV or −40 mV, respectively. The internal solution contained the following (in mM): 180 N-methyl-D-glucamine, 40 HEPES, 4 MgCl2, 0.1 BAPTA, 12 phosphocreatine, 3 Na2ATP, 0.5 Na2GTP, and 0.1 leupeptin, pH 7.2–7.3, 265–270 mOsm. The external solution consisted of the following (in mM): 127 NaCl, 20 CsCl, 10 HEPES, 1 CaCl2, 5 BaCl2, 12 glucose, 0.001 TTX, and 0.02 glycine, pH 7.3–7.4, 300–305 mOsm. NMDA (100 μM) or GABA (100 μM) was applied to the cell for 2 s every 30 s to minimize desensitization-induced decrease of current amplitude. For the recording of action potentials (APs), whole-cell current-clamp recordings were performed with the internal solution containing (in mM): 125 K-gluconate, 10 KCl, 10 HEPES, 0.5 EGTA, 3 Na2ATP, 0.5 Na2GTP, 12 phosphocreatine, pH 7.25, 280 mOsm. Cells were perfused with ACSF, and membrane potentials were kept at −55 to −65 mV. A series of hyperpolarizing and depolarizing step currents were injected to measure intrinsic properties and to elicit APs. Spontaneous APs were recorded without current injection. For the recording of voltage-dependent sodium and potassium currents, cells (held at −70mV) were perfused with ACSF, and voltage steps ranging from −90 mV to +50 mV were delivered at 10mV increments. Data analyses were performed with Clampfit (Axon instruments) and Kaleidagraph (Albeck Software).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were done with the software Origin (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). The data were expressed as mean±s.e.m. (standard error of measurement). Unpaired, two tailed student’s t-tests were performed to evaluate whether two groups were significantly different from each other.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the research subjects who participated in this study; Thomas Guttuso, Jr. for patient referral; Stephen R. Tan and Anthony Dee for performing skin biopsy; Suchun Zhang for DA neuron differentiation protocol; Linzhao Cheng for information on iPSC derivation; Gahee Park for iPSC culture; Barbara Foster and Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) Mouse Tumor Model Resource (MTMR) for teratoma assay; and RPCI SKY Core Facility for karyotyping; RPCI Genomics Shared Resource for aCGH and DNA methylation studies. The work was supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, NYSTEM contract C024406, NIH grants NS061856, NS070276, NS071122, NSFC grant 30928006, and SUNY REACH.

Footnotes

Author contributions

J.F. designed the research and wrote the manuscript; H.J. generated the skin fibroblasts, iPSCs and neurons and performed most the analyses; Y.R. analyzed oxidative stress and dopaminergic markers, E.Y.Y. and P.Z. performed electrophysiological studies, which were designed and analyzed by Z.Y.; M.G. and Z.H. analyzed the iPSCs; G.A. performed histological identification of teratomas; K.N. provided patient skin biopsy.

Competing Financial Interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Lang AE, Lozano AM. Parkinson’s disease. First of two parts. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1044–1053. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy J. Genetic analysis of pathways to Parkinson disease. Neuron. 2010;68:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nuytemans K, Theuns J, Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C. Genetic etiology of Parkinson disease associated with mutations in the SNCA, PARK2, PINK1, PARK7, and LRRK2 genes: a mutation update. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:763–780. doi: 10.1002/humu.21277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimura H, et al. Familial Parkinson disease gene product, parkin, is a ubiquitin-protein ligase. Nat Genet. 2000;25:302–305. doi: 10.1038/77060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson TM, Dawson VL. The role of parkin in familial and sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25 (Suppl 1):S32–S39. doi: 10.1002/mds.22798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitada T, et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392:605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez FA, Palmiter RD. Parkin-deficient mice are not a robust model of parkinsonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2174–2179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409598102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maherali N, et al. A high-efficiency system for the generation and study of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan Y, et al. Directed differentiation of dopaminergic neuronal subtypes from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:781–790. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chambers SM, et al. Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:275–280. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danielian PS, McMahon AP. Engrailed-1 as a target of the Wnt-1 signalling pathway in vertebrate midbrain development. Nature. 1996;383:332–334. doi: 10.1038/383332a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhee YH, et al. Protein-based human iPS cells efficiently generate functional dopamine neurons and can treat a rat model of Parkinson disease. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2326–2335. doi: 10.1172/JCI45794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takenaga M, Fukumoto M, Hori Y. Regulated Nodal signaling promotes differentiation of the definitive endoderm and mesoderm from ES cells. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2078–2090. doi: 10.1242/jcs.004127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boulting GL, et al. A functionally characterized test set of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:279–286. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang H, Jiang Q, Liu W, Feng J. Parkin suppresses the expression of monoamine oxidases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8591–8599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang H, Jiang Q, Feng J. Parkin increases dopamine uptake by enhancing the cell surface expression of dopamine transporter. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54380–54386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409282200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giros B, et al. Cloning, pharmacological characterization, and chromosome assignment of the human dopamine transporter. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;42:383–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee FJ, Pristupa ZB, Ciliax BJ, Levey AI, Niznik HB. The dopamine transporter carboxyl-terminal tail. Truncation/substitution mutants selectively confer high affinity dopamine uptake while attenuating recognition of the ligand binding domain. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20885–20894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torres GE, et al. Oligomerization and trafficking of the human dopamine transporter. Mutational analysis identifies critical domains important for the functional expression of the transporter. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2731–2739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenner P, Olanow CW. Oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1996;47:S161–S170. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.6_suppl_3.161s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shih JC, Chen K, Ridd MJ. Monoamine oxidase: from genes to behavior. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:197–217. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:795–803. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dawson TM, Ko HS, Dawson VL. Genetic animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2010;66:646–661. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen BT, Rice ME. Novel Ca2+ dependence and time course of somatodendritic dopamine release: substantia nigra versus striatum. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7841–7847. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07841.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel JC, Witkovsky P, Avshalumov MV, Rice ME. Mobilization of calcium from intracellular stores facilitates somatodendritic dopamine release. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6568–6579. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0181-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fallon L, et al. A regulated interaction with the UIM protein Eps15 implicates parkin in EGF receptor trafficking and PI(3)K-Akt signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:834–842. doi: 10.1038/ncb1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Best JA, Nijhout HF, Reed MC. Homeostatic mechanisms in dopamine synthesis and release: a mathematical model. Theor Biol Med Model. 2009;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pavese N, et al. In vivo assessment of brain monoamine systems in parkin gene carriers: a PET study. Exp Neurol. 2010;222:120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ribeiro MJ, et al. A multitracer dopaminergic PET study of young-onset parkinsonian patients with and without parkin gene mutations. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1244–1250. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.063529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olanow CW, et al. A double-blind, delayed-start trial of rasagiline in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1268–1278. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren Y, Jiang H, Ma D, Nakaso K, Feng J. Parkin degrades estrogen-related receptors to limit the expression of monoamine oxidases. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1074–1083. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Willy PJ, et al. Regulation of PPARgamma coactivator 1alpha (PGC-1alpha) signaling by an estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRalpha) ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8912–8917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401420101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.da Costa CA, et al. Transcriptional repression of p53 by parkin and impairment by mutations associated with autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinson’s disease. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1370–1375. doi: 10.1038/ncb1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu BY, et al. Neural differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells follows developmental principles but with variable potency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4335–4340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910012107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang XQ, Zhang SC. Differentiation of neural precursors and dopaminergic neurons from human embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;584:355–366. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-369-5_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chambers SM, et al. Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:275–280. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang H, Ren Y, Zhao J, Feng J. Parkin protects human dopaminergic neuroblastoma cells against dopamine-induced apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1745–1754. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuen EY, et al. Mechanisms for acute stress-induced enhancement of glutamatergic transmission and working memory. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:156–170. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.