Abstract

Postoperative or pressure alopecia (PA) is an infrequently reported group of scarring and non-scarring alopecias. It has been reported after immobilization of the head during surgery and following prolonged stays on intensive care units, and may be analogous to a healed pressure ulcer. This review presents a summary of cases published in pediatrics and after cardiac, gynecological, abdominal and facial surgeries. PA may manifest as swelling, tenderness, and ulceration of the scalp in the first few postoperative days; in other cases, the alopecia may be the presenting feature with a history of scalp immobilization in the previous four weeks. The condition may cause considerable psychological distress in the long term. Regular head turning schedules and vigilance for the condition should be used as prophylaxis to prevent permanent alopecia. A multi-center study in high-risk patients would be beneficial to shed further light on the etiology of the condition.

Keywords: Alopecia, immobilization, postoperative alopecia, pressure alopecia

INTRODUCTION

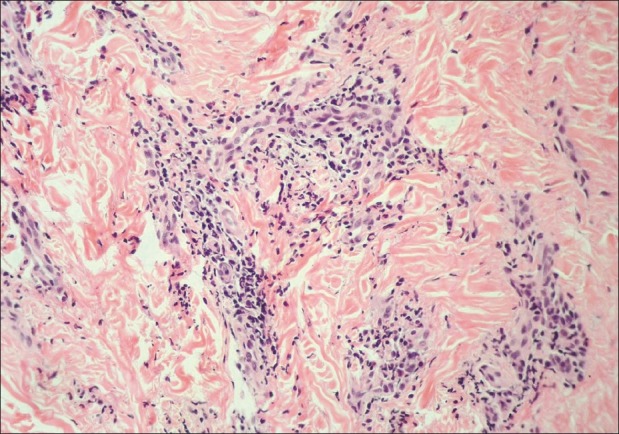

Postoperative or pressure alopecia (PA) is the term used to describe a group of scarring and non-scarring alopecias that occur following ischemic changes to the scalp, with a pathophysiology similar to pressure ulcers. The condition was first described by RR Abel and GM Lewis, who presented a series of eight cases to the annual meeting of the American Dermatological Society in 1959.[1] PA typically presents with a discrete area of alopecia, usually in the occiput, within a few weeks of surgery or a prolonged period in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Some patients experience tenderness, swelling, or ulceration in the scalp prior to the alopecia, but in others, the alopecia may be the presenting feature. If recognized early, the condition may be reversible, or even preventable; a delayed diagnosis could lead to permanent hair loss [Figure 1]. There is no definitive histopathological appearance for PA; various findings have been described in the literature. Fibrosis with loss of hair follicles has been noted in those with scarring alopecia [Figure 2]. Other findings that have been reported include chronic inflammation and foreign body granulomatous reactions; Hanly et al.[2] found multiple catagenic hair follicles and apoptotic bodies without inflammation.

Figure 1.

Areas of scarring alopecia in vertex of the scalp; patient was previously in ICU for 4 weeks

Figure 2.

Increased collagen with scarring in dermis associated with a lack of hair follicles (H and E)

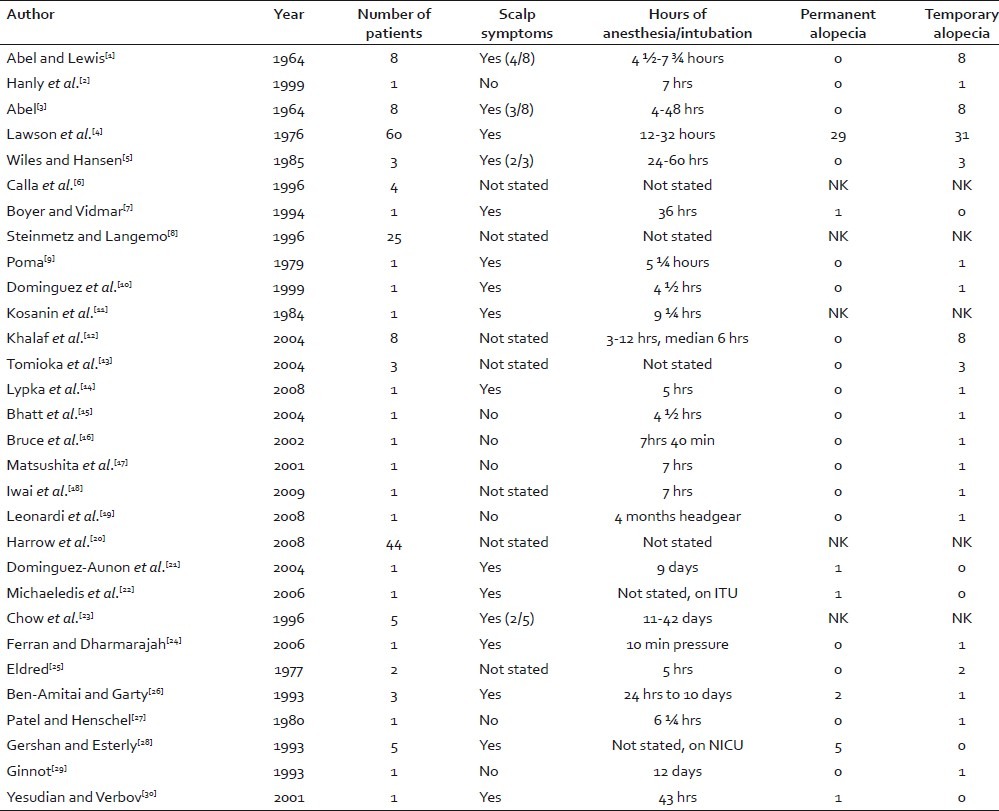

Since Abel's early work,[1,3] there have been more than 100 cases of PA described in the literature [Table 1].

Table 1.

Summary of previous reports of pressure alopecia

CARDIAC SURGERY

PA has been most commonly reported following cardiac surgery. Lawson et al.[4] conducted retrospective and prospective searches for cases of PA following coronary artery bypass grafting at a tertiary referral center. They reported an incidence of 7% in the retrospective study (n=225). In the prospective phase the following year, they found an incidence of 14% in patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (n=230). The third year of the study found an incidence of 4% in 280 patients. A total of 60 cases of alopecia were identified in the 735 patients in the study (8.2%). They concluded that PA was under-reported and missed if not actively sought. A variable degree of symptoms prior to hair loss was noted.[4]

Lawson et al.[4] were the first to report permanent alopecia following surgery, and believed that the duration of surgery was directly correlated with the probability of the alopecia being permanent. In this series the 29 patients who developed permanent alopecia had been intubated on average ten hours longer than the 31 patients whose alopecia was temporary.[4] They influenced the development of alopecia with different head turning schedules; when the head was turned every thirty minutes during the procedure and postoperatively, the incidence of PA was zero.[4]

Following Lawson's study, further cases were reported in patients aged 9 to 73 years undergoing cardiac surgery,[5,6] with longer times spent on cardiopulmonary bypass leading to increased risk of permanent alopecia.[6] Boyer and Vidmar identified PA in a 79-year-old man who underwent coronary artery surgery.[7] Biopsy of the scalp four weeks after surgery showed fibrosis and inflammation in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis associated with lack of anagen hairs, with all follicles in catagen phase. There was necrosis of some hair bulb cells and in contrast to Abel and Lewis’ findings, there was no vasculitis.[1]

In 1996, Steinmetz and Langemo[8] measured the tissue interface pressures at the occiput of 25 volunteers undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. It was consistently higher than the maximum normal capillary tissue interface pressure, thus placing the patients at risk of developing pressure ulceration at the occiput during surgery. They recommended regular head repositioning during surgical procedures to avoid occipital pressure sores and alopecia,[8] reiterating what had been recommended by Lawson et al. twenty years earlier.[4]

GYNECOLOGICAL AND BREAST SURGERY

Abel and Lewis described eight patients with hair loss in the vertex of the scalp within twenty-eight days of gynecological surgery.[1] All had undergone surgery in the Trendelenburg position for three hours or more. Five of the eight patients had experienced crusting and tenderness of the scalp prior to the hair loss. Three women had noticed only the alopecia. The authors performed biopsies of the scalps of six patients and found a vasculitis, with atrophic hair follicles in the areas of alopecia.[1] They hypothesized that the downward force of the weight of the patient's head on the same area of scalp during anesthesia caused temporary occlusion of small blood vessels in the scalp, leading to hypoxia at that site, and a subsequent vasculitis. The temporary cessation of the activity of the hair follicles resulted in reversible alopecia in the affected areas. They proved this hypothesis in animal models.[1]

In 1979, Poma published a further case of temporary PA following gynecological surgery.[9] The patient developed a seroma on the first postoperative day in the area subsequently affected by alopecia. The author recommended regular head repositioning as prophylaxis for the condition.[9]

Cases of PA have also been reported after breast surgery.[10,11] A 44-year-old female was intubated for over nine hours for reconstructive breast surgery, and noted alopecia in an area on her occiput which developed following erythema, swelling, and exudation on the third postoperative day. The authors surveyed their surgical colleagues, and found that the majority were not aware of PA.[11]

ABDOMINAL SURGERY

Published literature of PA following abdominal surgery is limited. Temporary PA has been reported in both donors and recipients of liver transplants.[12,13] Khalaf et al., who reported PA in four patients who had been donors or recipients of liver transplants and four patients who had cardiac surgery, hypothesized that psychiatric comorbidities had a role in the development of PA.[12]

Hanly et al. reported a case of temporary PA in a 21-year-old female who had biliary surgery with a total anesthesia time greater than nineteen hours. Biopsy of the patient's scalp showed all hair follicles to be in the catagen phase, with apoptotic bodies in the follicular epithelium and no evidence of inflammation. They concluded that hypoxia secondary to pressure had caused all hair follicles to enter programmed cell death.[2]

MAXILLOFACIAL/ORTHODONTIC/OPHTHALMOLOGICAL SURGERY

Patients undergoing orthognathic surgery may be at increased risk of PA due to the length of surgery, the hypotensive anesthesia used, and the forces transmitted through the head during osteotomies. A 37-year-old woman who underwent five-hour orthognathic surgery developed an area of temporary alopecia to her vertex three weeks following surgery; it resolved within six months.[14]

There have been case reports of PA following shorter procedures such as breast[10] and ophthalmic[15] surgery.

The difficulties of repositioning the head during head and neck surgery were raised by Bruce et al.[16] who reported temporary alopecia corresponding to the shape of a horseshoe head rest used for a maxillectomy operation lasting more than seven hours. A similar case was published recently in a 29-year-old male, who developed temporary PA following seven hours of surgery for distraction osteogenesis.[17]

PA may be caused by pressure from headbands rather than from the head resting for a prolonged period on an area of scalp. Temporary alopecia due to a headband used to secure a frame to a patient's head for maxillary surgery has been reported. The headband was applied for seven hours.[18]

In 2008, Leonardi et al.[19] documented a case of PA from use of orthodontic headgear. A 14-year-old boy developed two sites of temporary alopecia on his parietal/occipital scalp corresponding directly to the sites of maximal pressure from his orthodontic head gear.[19] It may be the first report of PA in a fully conscious patient, and raises the question as to why the discomfort did not cause the patient to loosen his appliance and relieve the pressure.

TRAUMA

Occipital pressure ulcers leading to alopecia have been documented in injured soldiers. In a retrospective prevalence study, Harrow et al.[20] noted pressure ulcers in military personnel admitted to a polytrauma rehabilitation center in North America. They found a prevalence of 38% for all pressure ulcers (sacral, heel and occipital) in their admissions (65/165 admissions). When narrowed to include only those admitted from active service in Iraq (88 patients) who had a higher prevalence of pressure ulcers (53%), 50% of the non-stage one pressure injuries (n=26) were occipital, and 100% of the severe pressure ulcers seen were occipital (n=4). They found evidence that cervical collar use could be contributory.[20]

Further cases following trauma include a 23-year-old man who was unconscious in an ICU for nine days following a motorcycle accident. He developed an area of inflammation on his scalp, with subsequent alopecia which was still present eighteen months later. Biopsy of the scalp revealed dilated destroyed hair follicles, a neutrophil-rich infiltrate and a foreign body granulomatous reaction.[21]

PA after a motorcycle accident was described in a patient who had been admitted to ICU suffering from facial injuries.[22] PA has also been documented in five intubated burns patients aged 27 to 71 years who were ventilated for eleven to forty-two days; the alopecia was permanent in some of the patients.[23]

Ferran and Dharmarajah[24] reported a case of PA after direct blunt trauma to an area. A 27-year-old man who became trapped between a lorry and trailer for ten minutes with direct pressure to his head noted hair loss shortly after his accident. Five weeks later, he still had the area of alopecia, which resolved within five months. This was reported as PA following blunt trauma. However, it was concluded that ten minutes of pressure was unlikely to cause PA and it was more likely shear and frictional forces which caused the loss of hair.[24]

PEDIATRIC

The phenomenon of PA is not exclusive to adults. It has been described in children and neonates postoperatively and following stays on ICU.

In 1977, Eldred reported two cases of alopecia following chest wall surgery in children. Both developed temporary occipital alopecia following immobilization of the head during surgery.[25]

Ben-Amitiai and Garty[26] described three cases of children aged 10 months to 2 years undergoing cardiac surgery with intubation times between twenty-four hours and ten days. They developed crusting of the occipital scalp within a few days postoperatively. Two infants had permanent alopecia of the area. There was no correlation between the duration of intubation and the regrowth of hair in this series.[26]

A 15-year-old girl developed temporary symptomless alopecia following breast surgery lasting more than six hours. The hair loss corresponded to the shape of the soft doughnut-shaped head rest which had been used during surgery.[27] A doughnut-shaped head rest was one of the possible solutions offered by Abel and Lewis[1] to the problem of PA. In this case, it was insufficient to prevent the development of alopecia.

The head is required to be still during ophthalmological surgery and there has been a case of temporary PA in an 11-year-old boy following surgery for retinal detachment.[15]

The first descriptions of PA in neonatal ICU appeared in 1993.[28] Five term neonates of normal birth weight developed occipital pressure ulcers which progressed to scarring alopecia. All had severe cardiac problems and had suffered episodes of hypoxemia/hypoperfusion requiring vasopressor therapy and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The authors hypothesized that hypoxia, acidosis, and prolonged immobilization of the neonates’ heads had contributed to the development of the ulcers and increased the risk of permanent alopecia. The department subsequently introduced a turning schedule, and in the following six months saw no further cases of occipital pressure ulcers or alopecia. Poor nutrition may have been a contributing factor as four of the infants were hypoalbuminemic. The authors highlighted that the alopecia may have lasting psychological effects on the infants and their parents.[28]

Further cases of children developing PA after periods of sedation without surgery were described, such as the case of an 11-year-old boy described by Ginnot.[29] The boy was intubated for twelve days, after being admitted to hospital with cardiac failure secondary to myocarditis. He had been hypotensive and required vasopressors during his admission to ICU, and on the fortieth day after admission, noticed an area of alopecia in his occiput. It resolved spontaneously within a month.[29]

Yesudian and Verbov[30] described a 5-year-old boy who had been sedated for forty-three hours on ICU following a road traffic accident. He developed soreness and scabbing on his occiput whilst in intensive care and a few months later, scarring alopecia was noted at that site. The child had developed a concurrent sacral pressure ulcer.[30]

CONCLUSION

PA is probably underreported. It occurs following hypotensive or complicated surgery and prolonged stays in ICU, when patients require intubation. The constant pressure on the scalp is causative and may be exacerbated by hypoxemia or hypotension. There may be some correlation between the length of time spent under anesthesia and the development of permanent alopecia. Reports confirm that regular head turning schedules eliminate the problem, and this should be advocated as prophylaxis to avoid permanent alopecia. A prospective multi-center study in high-risk cohorts (those undergoing prolonged surgery and patients intubated for long periods on ICU) may shed further light on this enigmatic condition.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abel RR, Lewis GM. Postoperative (pressure) alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:34–42. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1960.03730010038004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanly AJ, Jorda M, Badiavas E, Valencia I, Elgart GW. Postoperative pressure-induced alopecia: Report of a case and discussion of the role of apoptosis in non-scarring alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:357–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1999.tb01857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abel RR. Postoperative (pressure) alopecia. Anesthesiology. 1964;25:869–71. doi: 10.1097/00000542-196411000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawson NW, Mills NL, Ochsner JL. Occipital alopecia following cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1976;71:342–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiles JC, Hansen RC. Postoperative (Pressure) alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:195–8. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)80016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calla S, Patel S, Shashtri N, Shah D. Occipital alopecia after cardiac surgery. Can J Anaesth. 1996;43:1180–1. doi: 10.1007/BF03011850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyer JD, Vidmar DA. Postoperative alopecia: A case report and literature review. Cutis. 1994;54:321–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinmetz JA, Langemo DK. Changes in occipital capillary perfusion pressures during coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Adv Wound Care. 1996;9:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poma PA. Pressure-induced alopecia: Report of a case after gynaecologic surgery. J Reprod Med. 1979;22:219–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dominguez E, Eslinger MR, McCord SV. Postoperative (pressure) alopecia: Report of a case after elective cosmetic surgery. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1062–3. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199910000-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kosanin RM, Riefkohl R, Barwick WJ. Postoperative alopecia in a woman after a lengthy plastic surgical procedure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:308–9. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198402000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khalaf H, Negmi H, Hassan G, Al-Sebayel M. Postoperative alopecia areata: Is pressure-induced ischemia the only cause to blame? Transplant Proc. 2004;36:2158–9. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.08.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomioka T, Hayashida M, Hanaoka K. Pressure alopecia in living donors for liver transplantation. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:186–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03018783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lypka MA, Yamashita DD, Urata MM. Postoperative alopecia following orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:1957–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatt HK, Sharma MC, Blair NP. Pressure alopecia following vitreoretinal surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:191–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00806-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruce IA, Simmons MA, Hampal S. ‘Horseshoe-shaped’ post-operative alopecia following lengthy head and neck surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116:230–2. doi: 10.1258/0022215021910429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsushita K, Inoue N, Ooi K, Totsuka Y. Postoperative pressure-induced alopecia after segmental osteotomy at the upper and lower frontal edentulous areas for distraction osteogenesis. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;15:161–3. doi: 10.1007/s10006-010-0231-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwai T, Matsui Y, Hirota M, Tohnai I, Maegawa J. Temporary alopecia caused by pressure from a headband used to secure a reference frame to the head during navigational surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;7:573–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leonardi R, Lombardo C, Loreto C, Caltabiano R. Pressure alopecia from orthodontic headgear. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:456–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrow JJ, Rashka L, Fitzgerald SG, Nelson AL. Pressure ulcers and occipital alopecia in Operation Iraqi Freedom polytrauma casualties. Mil Med. 2008;173:1068–72. doi: 10.7205/milmed.173.11.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dominguez-Aunon JD, Garcia-Arpa M, Perez-Suarez B, Castano E, Rodriguez Peralto JL, Guerra A, et al. Pressure Alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:928–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michaelidis IG, Stefanopoulos PK, Papadimitriou GA. The triple rotation scalp flap revisited: A case of reconstruction of cicatrical pressure alopecia. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:1153–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chow IJ, Balakrishnan C, Meininger MS. Alopecia of the unburned scalp. Burns. 1996;22:250–1. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferran NA, Dharmarajah R. Pressure alopecia following blunt trauma. Injury Extra. 2006;37:200–1. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eldred WJ. Occipital alopecia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1977;73:322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben-Amitai D, Garty BZ. Alopecia in children after cardiac surgery. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:32–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1993.tb00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel KD, Henschel EO. Postoperative alopecia. Anesth Analg. 1980;59:311–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gershan LA, Esterly NB. Scarring alopecia in neonates as a consequence of hypoxaemia-hypoperfusion. Arch Dis Child. 1993;68:591–3. doi: 10.1136/adc.68.5_spec_no.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ginnot N. Alopecia. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:390–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1993.tb00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yesudian PD, Verbov JL. Scalp alopecia as a result of immobilization following a traffic accident. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:540–1. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.1862011c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]