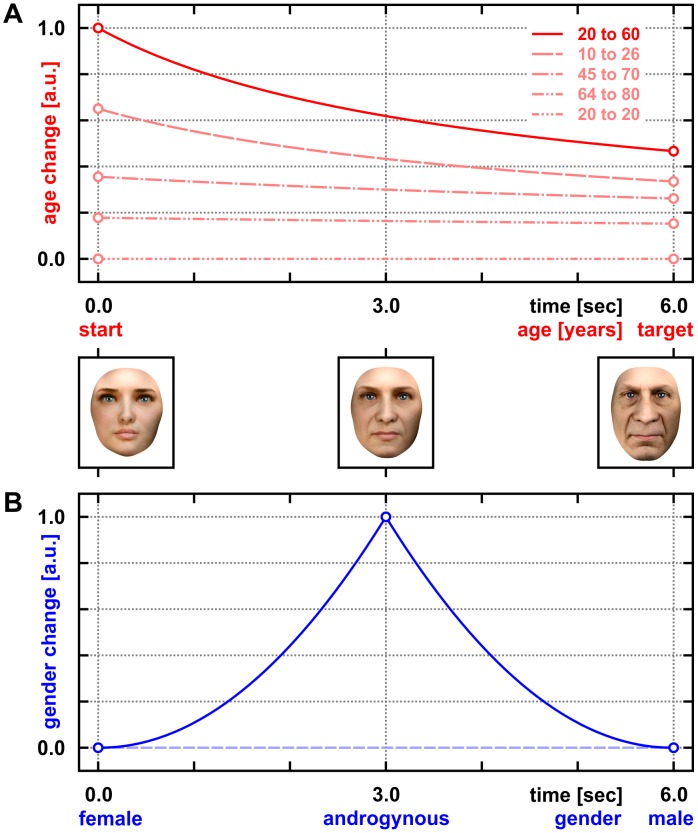

Figure 3. Modeling changes of age and gender during face morphing.

Both were time-binned at the video frame rate (24 fps) and scaled to maxima of 1.0 arbitrary units [a.u.]. (A) Differential age change encoded according to Stevens' law of psychophysics (using a power exponent of 0.3; Figure 2A). Note that relative facial aging was up-weighted to initial periods of the example morph (also see Figure 1A; here: solid red line) and, for identical age differences, to younger absolute ages, i.e. aging from 10 to 26 was assumed to provide a stronger stimulus with more visual cues than aging from 64 to 80 years (dashed vs. double-dotted/dashed line). (B) Differential gender change expressed by the first derivative of the function plotted in Figure 2C. Note that peak androgyny was defined as the effective stimulus-of-interest, i.e. the transition of facial gender was emphasized at the center of the morph (see also Figure 1A and Movie S1). Half of the morphs contained no gender transitions, retaining a flat line at zero level to indicate the lack of gender change (dashed line).