Abstract

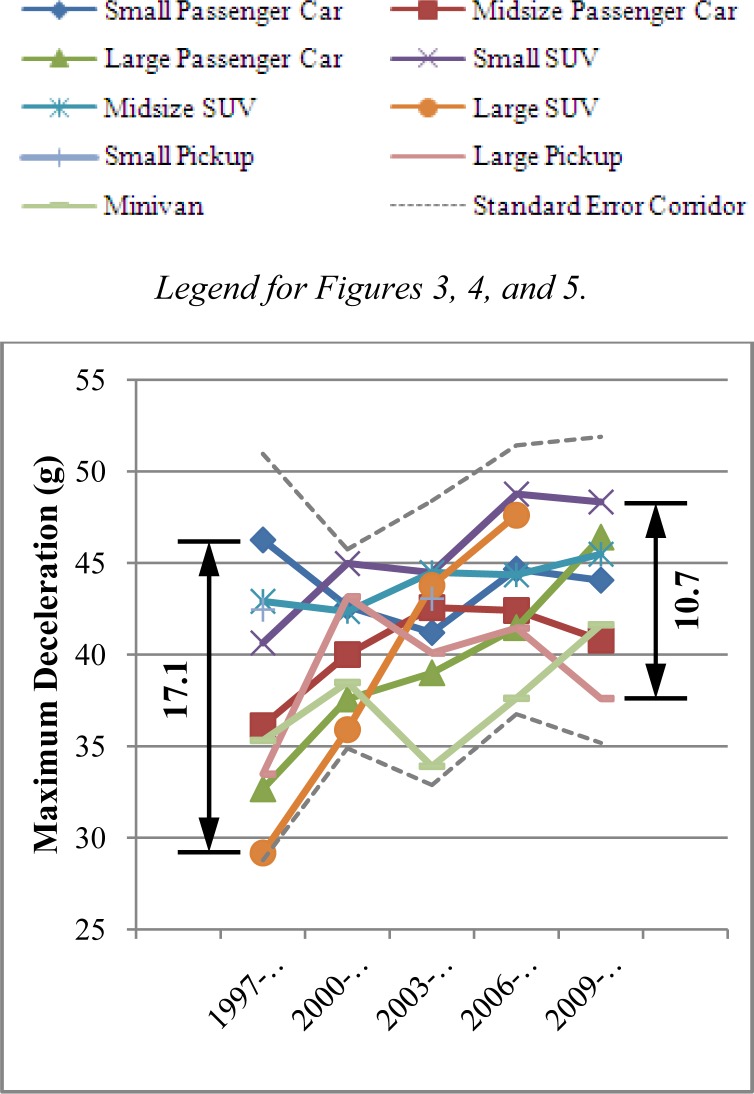

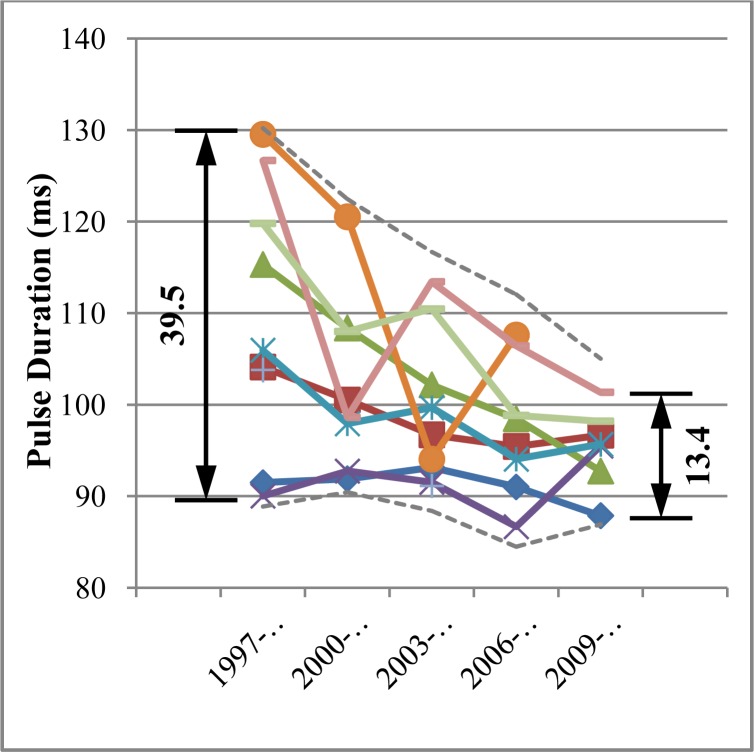

Full-scale vehicle crash tests are performed globally to assess vehicle structure and restraint system performance. The crash pulse, captured by accelerometers mounted within the occupant compartment, measures the motion of the vehicle during the impact event. From an occupant’s perspective, the crash pulse is the inertial event to which the vehicle’s restraint systems must respond in order to mitigate the forces and accelerations that act on a passenger, and thus reduce injury risk. The objective of this study was to quantify the characteristics of crash pulses for different vehicle types in the contemporary North American fleet, and delineate current trends in crash pulse evolution. NHTSA and Transport Canada crash test databases were queried for full-frontal rigid barrier crash tests of passenger vehicles model year 2000–2010 with impact angle equaling zero degrees. Acceleration-time histories were analyzed for all accelerometers attached to the vehicle structure within the occupant compartment. Custom software calculated the following crash pulse characteristics (CPCs): peak deceleration, time of peak deceleration, onset rate, pulse duration, and change in velocity. Vehicle body types were classified by adapting the Highway Loss Data Institute (HLDI) methodology, and vehicles were assigned a generation start year in place of model year in order to more accurately represent structural change over time. 1094 vehicle crash tests with 2795 individual occupant compartment-mounted accelerometers were analyzed. We found greater peak decelerations and and shorter pulse durations across multiple vehicle types in newer model years as compared to older. For midsize passenger cars, large passenger cars, and large SUVs in 56 km/h rigid barrier tests, maximum deceleration increased by 0.40, 0.96, and 1.57 g/year respectively, and pulse duration decreased by 0.74, 1.87, and 2.51 ms/year. We also found that the crash pulse characteristics are becoming more homogeneous in the modern vehicle fleet; the range of peak deceleration values for all vehicle classes decreased from 17.1 g in 1997–1999 generation start years to 10.7 g in 2009–2010 generation years, and the pulse duration range decreased from 39.5 ms to 13.4 ms for the same generation year groupings. This latter finding suggests that the designs of restraint systems may become more universally applicable across vehicle body types, since the occupant compartment accelerations are not as divergent for newer vehicles.

INTRODUCTION

Characteristics of vehicle motion during an impact are described by the “crash pulse”, i.e. the deceleration versus time history collected at a location within the crashed vehicle. This data is typically gathered in three dimensions by linear accelerometers mounted at various locations on the vehicle structure such as the B-pillar, seat pan, and/or door sill. Vehicle acceleration directly influences occupant kinematics(Grimes 2000, Cao 2004, Cheng 2006), and may lead to differences in the time at which the occupant loads the belt or contacts elements of the vehicle interior, or the speed differential between the occupant and vehicle interior. Thus, the crash pulse is a key contributing factor to the development of restraint systems that modify occupant kinematics to mitigate injury.

Previous studies of vehicle crash pulse characteristics have included limited populations of vehicles. Linder et al. (2003) quantified pulse characteristics for 16 rigid barrier and vehicle-to-vehicle rear impact tests, finding variations in time duration from 65–130 ms for similar delta-V values (10.2–19.4 km/h). Glass(2002) examined 86 vehicles in 48 km/h (30 mph) and 56 km/h (35 mph)full-frontal rigid barrier tests using a point-by-point averaging of the time histories to determine peak deceleration, change in velocity, and crash pulse time duration by vehicle class and test speed. For 48 km/h tests averaged across all vehicles classes, the peak deceleration was 22.6 g and the time duration was 122 ms. For 56 km/h tests, the average peak deceleration was 28.7 g and the duration was 120 ms.

There is some evidence that crash pulse characteristics such as those reported by Glass are changing with time. Park et al. (1999) reviewed 56 km/h full-frontal rigid barrier crash tests of 175 light trucks, vans, and SUVs of model years 1983–1998. In addition to assessing vehicle stiffness, peak deceleration and time duration pulse characteristics were also examined. Park found a non-significant overall decrease in maximum deceleration within the vehicle occupant compartment (33.7 g in 1983–1991 model years vs. 30.8 g in 1996–1998 model years), and a non-significant increase in pulse duration (116 ms in 83–91 vs. 120 ms in 96–98). In 2007, Bendjellal examined frontal EuroNCAP crash pulses for two vehicles of the same model and successive generations (model years included 2000–2006) for each of the super-mini (i.e. subcompact), family (i.e. sedan), and MPV (i.e. minivan) classes, showing greater peak deceleration and shorter crash pulse duration for each of the newer generation vehicles. This difference was particularly notable in the family vehicle (approximately 57% increase in peak deceleration and 15% decrease in time duration between 2004 and 2006), and MPV (approximately 33% increase in peak deceleration and 21% decrease in pulse duration between 2003 and 2006). These anecdotal studies of recent model year vehicles reveal trends in crash pulses that potentially persist in the entire vehicle fleet. Thus, the purpose of the current study was to elucidate crash pulse characteristics in a large sample of crash tests. We quantified the crash pulse characteristics (maximum deceleration, time of maximum deceleration, onset rate, pulse duration, delta-V) for a large population of vehicles of diverse classes in the 2000–2010 model year range. This cohort was exposed to full-frontal crash tests at 40, 48, and 56 km/h (25, 30, 35 mph) closing speeds.

METHODS

Data was gathered from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA)and Transport Canada (TC) crash test databases. Inclusion criteria consisted of passenger vehicles model years 2000–2010, in full-frontal rigid-barrier tests with an impact angle of 0 degrees (i.e. vehicle path of travel is perpendicular to barrier face), and with at least one accelerometer attached to the vehicle occupant compartment. Tests were excluded if crash test setup data was incomplete or miscoded, if sensor failure was indicated by the test laboratory, or if the vehicle generation start year (defined below) was prior to 1997. Accelerometer data was also excluded if the integrated acceleration (delta-V) was less than the closing speed, as it is physically impossible for this phenomenon to occur; a delta-V less than a closing speed would indicate that the vehicle never stopped despite contact with the barrier.

Vehicle Class

In order to unify vehicle classification systems across multiple test centers, a modified version of the Highway Loss Data Institute (HLDI) classification system (Highway Loss Data Institute, 2009) was employed. The HLDI classification assigns both a vehicle class (e.g. passenger car, SUV, pickup) and size, which is based on the vehicle curb weight and shadow (vehicle length times width). For our study, vehicle size was further simplified by grouping “micro”, “mini”, and “small” vehicles together under the heading “small”, and grouping “large” and “very large” vehicles were under the heading “large”. “Midsize” vehicles kept the midsize classification. All minivans were grouped together in their own category. Vehicles not previously classified by the Highway Loss Data Institute were individually classified using the HLDI criteria based on weight and dimensions.

Vehicle Generation Start Year

Each vehicle was assigned a vehicle generation start year in place of the model year. A vehicle generation consists of several model years, wherein all cars from a particular generation share the same overall structure (given the same trim level, body style, engine option, etc.). Because vehicle structure does not typically change from year-to-year within a vehicle generation, for example, a model year 2002 sedan of a particular make and model may be effectively the same as a model year 2006 from a crash performance perspective. Vehicle updates known as “facelifts”, which typically change only cosmetic aspects of the vehicle’s exterior or interior styling, were not considered to be a generational change. Using the Vehicle Year and Model Interchange List (a.k.a. Sisters & Clones list; Anderson, 2011) as a reference, each of the included vehicles was assigned a vehicle generation start year in place of their actual model year for all year-based analyses. Vehicles with a generation start year before 1997 were excluded.

Crash Pulse Characteristics

For each vehicle accelerometer within the occupant compartment, the x-direction acceleration-time history was downloaded and processed using a custom computer program (MATLAB, Natick, MA). The coordinate system was defined per the SAE J211 sign convention, in which the x-direction is parallel to the vehicle path of travel immediately prior to striking the barrier. Vehicle acceleration data was filtered at CFC 60/100 Hz (Society of Automotive Engineers, 1995). The following crash pulse characteristics (CPCs) were calculated for each acceleration-time curve (Figure 1):

Maximum deceleration —most negative acceleration value (g)

Time of maximum deceleration (ms)

Onset rate – maximum deceleration divided by time of maximum deceleration (g/s)

Pulse duration – as defined below(ms)

Delta-V – maximum change in velocity (i.e. integral of the deceleration-time curve over the pulse duration) (km/h)

Figure 1.

Exemplar crash pulse for a 56 km/h (35 mph) frontal rigid barrier test showing calculated parameters of interest.

Pulse Duration

Pulse duration presented challenges to calculate. We found no standard method for the calculation of pulse duration in the literature. In general, pulse duration has been qualitatively defined as the duration of time from vehicle-to-barrier contact to the point at which the acceleration curve “settles” to zero after the primary acceleration. One possible qualitative method defines the end of the crash pulse as the time when the acceleration returns or crosses zero after the maximum acceleration (Glass 2002). This method is ineffective for acceleration curves that cross the x-axis several times after peak acceleration while still generating change in velocity, or curves that never cross the x-axis after the peak acceleration (presumably due to shift in sensor axis alignment during the crash). Linder et al. (2003) considered the pulse duration to be the time at which the acceleration curve crossed the x-axis after 90% of the delta-V had occurred. We employed this method on a subset of our data and found it to be accurate in most cases, but ineffective for cases where the acceleration does not completely return to zero, or in cases where the acceleration crossed zero immediately after achieving 90% of delta-V (potentially cutting off data collection before impact event was complete).

Building on Linder’s approach, we developed a novel method for calculating pulse duration. First, the acceleration curve was filtered to 30 Hz (corresponding to CFC 18) to smooth extreme oscillations. Next, the filtered acceleration curve was traced backwards from the last time point in the signal until the signal magnitude equaled the average acceleration from 0–200 ms (approximately 25% of the maximum acceleration). Then, the signal was traced forwards to the point where the CFC 18 filtered acceleration magnitude equaled 5% of the peak. The time at which this value occurred was considered to be the end pulse time. Pulse duration for the signal equaled end pulse time minus the time at which the vehicle struck the barrier (time=0). Figure 2 compares this novel end pulse method for an exemplar crash pulse.

Figure 2.

Time parameters important to crash pulse duration, comparing existing duration calculation methods from Glass and Linder to novel methodology.

Analysis

CPCs were grouped by vehicle class, closing speed, and vehicle generation start year. Additional crash test setup variables including test performer and accelerometer location within the vehicle were also collected. Crash test setup variables and CPCs were imported into SAS Software (SAS Institute Inc., NC) for statistical analysis, and analyzed using both descriptive and inferential statistical techniques. Analysis occurred in two distinct phases. In phase I, descriptive statistics such as frequency distributions, histograms and measures of central tendency, variability, and association were computed for all relevant variables in the dataset. In order to use appropriate statistical methods, variables were tested for normality. In phase II, inferential statistical techniques were applied. The Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) technique with an unstructured correlation matrix was used to assess the association between vehicle generation year and each CPC, controlling for sensor location and test performer. Adjusted CPC means and vehicle generation year coefficients for each CPC were calculated. Robust variances were computed by using Taylor series linearization method and standard errors were estimated for all parameters. GEE modeling was used to account for the clustering of sensors within vehicles and test labs which implies that CPCs calculated from different sensors are correlated, i.e. non-independent. Analyses were stratified by vehicle type and closing speed. Statistical significance was achieved when p<0.05.

RESULTS

1137 full-scale vehicle-to-rigid barrier crash tests met the inclusion criteria, yielding a total of 2980 separate accelerometer signals, due to multiple accelerometers located within the passenger compartment of most vehicles. Twenty-three accelerometer signals were excluded due to missing data, 29 signals were excluded due to accelerometer failure, and 31 signals were excluded when the calculated delta-V value was less than the reported closing speed (hypothesized to be caused by either: 1) the direction of the sensitive axis of the accelerometer changed during impact due to underlying structure deformation, or 2) the sensor failed during the crash causing only a portion of the acceleration to be measured). We then stratified the cohort by the following crash test setup categories: test performer, target test speed, vehicle class, and accelerometer location (Table 1a). Any unique crash test setup sub-category with fewer than 25 total accelerometer signals was excluded due to low sample size. Twenty-five signals were eliminated due to small samples of accelerometer location (floorpan tunnel, rear frame crossmember), and 32 sensors were excluded for target closing speed (23 km/h, 20 mph, 35 km/h, unspecified). The population was also stratified by vehicle generation start year. For generation start years prior to 1997, no unique year had more than 25 accelerometer signals available, thus these years were excluded (45 signals). A total of 2795 sensor locations in 1094 vehicles were evaluated.

Table 1a.

Test population characteristics.

| Test Performer | N signals (%) | N vehicles (%) |

| Calspan | 390 (14%) | 150 (14%) |

| Karco Engineering | 417 (15%) | 197 (18%) |

| MGA Research | 463 (17%) | 217 (20%) |

| Transport Canada | 1322 (47%) | 451 (41%) |

| TRC | 203 (7%) | 79 (7%) |

| Target Test Speed | N signals (%) | N vehicles (%) |

| 40 km/h (25 mph) | 406 (15%) | 169 (15%) |

| 48 km/h (30 mph) | 984 (35%) | 343 (31%) |

| 56 km/h (35 mph) | 1405 (50%) | 582 (53%) |

| Vehicle Class | N signals (%) | N vehicles (%) |

| Small Passenger Car | 783 (28%) | 298 (27%) |

| Midsize Passenger Car | 613 (22%) | 241 (22%) |

| Large Passenger Car | 270 (10%) | 103 (9%) |

| Small SUV | 193 (7%) | 77 (7%) |

| Midsize SUV | 379 (14%) | 158 (14%) |

| Large SUV | 109 (4%) | 43 (4%) |

| Small Pickup | 68 (2%) | 28 (3%) |

| Large Pickup | 156 (6%) | 64 (6%) |

| Minivan | 224 (8%) | 82 (7%) |

| Accelerometer Location | N signals (%) | N vehicles (%) |

| Floorpan - Left Rear | 248 (9%) | - |

| Floorpan - Right Rear | 242 (9%) | - |

| Rear Deck | 48 (2%) | - |

| Seat - Left Rear | 254 (9%) | - |

| Seat - Right Rear | 258 (9%) | - |

| Sill - Left Front | 437 (16%) | - |

| Sill - Left Rear | 207 (7%) | - |

| Sill - Right Front | 441 (16%) | - |

| Sill - Right Rear | 185 (7%) | - |

| Vehicle CG | 475 (17%) | - |

Test Population

The text below describes the population by individual accelerometer location (i.e. a test involving a vehicle with accelerometers at three different locations within the occupant compartment is counted three times). To see descriptive statistics of the included population by vehicle, refer to Tables 1a and 1b.

Table 1b.

Test population characteristics (continued).

| Vehicle Model Year | Vehicle Generation Start Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N signals (%) | N vehicles (%) | N signals (%) | N vehicles (%) | |

| 1997 | - | - | 74 (3%) | 26 (2%) |

| 1998 | - | - | 129 (5%) | 45 (4%) |

| 1999 | - | - | 143 (5%) | 49 (4%) |

| 2000 | 144 (5%) | 46 (4%) | 303 (11%) | 108 (10%) |

| 2001 | 379 (14%) | 122 (11%) | 285 (10%) | 104 (10%) |

| 2002 | 233 (8%) | 93 (9%) | 233 (8%) | 95 (9%) |

| 2003 | 176 (6%) | 72 (7%) | 186 (7%) | 81 (7%) |

| 2004 | 270 (10%) | 113 (10%) | 206 (7%) | 89 (8%) |

| 2005 | 233 (8%) | 102 (9%) | 180 (6%) | 76 (7%) |

| 2006 | 285 (10%) | 115 (11%) | 254 (9%) | 101 (9%) |

| 2007 | 299 (11%) | 121 (11%) | 316 (11%) | 126 (12%) |

| 2008 | 262 (9%) | 109 (10%) | 139 (5%) | 56 (5%) |

| 2009 | 288 (10%) | 111 (10%) | 228 (8%) | 87 (8%) |

| 2010 | 226 (8%) | 90 (8%) | 116 (4%) | 50 (5%) |

Full-frontal crash tests were performed at one of five test centers: Transport Canada (Blainville, Quebec) (47%), MGA Research (Burlington, Wisconsin) (17%), Karco Engineering (Adelanto, California) (15%), Calspan (Buffalo, New York) (14%), and TRC (East Liberty, Ohio) (7%). The target closing speeds for accelerometers in the tested vehicles included 40 km/h (15%), 48 km/h (35%) or 56 km/h (50%).

The distribution of accelerometers by vehicle class was as follows: small passenger cars (28%), midsize passenger cars (22%), midsize SUVs (14%), large passenger cars (10%), minivans (8%), small SUVs (7%), large pickups (6%), large SUVs (4%), or small pickups (2%). Vehicle test weights ranged from 931.9–3185.6 kg, with an average test weight of 1851.6 ± 373.8 kg. Sensors were located within the vehicle occupant compartment at the front sill (16% left, 16% right, 31% overall), the rear seatpan (9% left, 9% right, 18% overall), the rear floorpan (9% left, 9% right, 18% overall), the vehicle CG (17%), the rear sill (7% left, 6% right, 14% overall), or the rear deck (2%). Sensors were nearly evenly distributed on either side of or along the vehicle axis of symmetry, with 41% on the left side, 40% on the right side, and 19% along the axis of symmetry. Vehicle model years were distributed as follows (Table 1b):model year 2000 represented the fewest overall sensor locations (5%), while model year 2001 had the greatest number of sensors (14%). Vehicle generation start years included at least 25 vehicles for each of the years 1997–2010, with the largest number of sensors in the 2007 generation start year vehicles (11%), and the smallest number in the model year extremes (3% in the 1997 vehicles, 4% in the 2010 vehicles).

CPCs by Vehicle Class and Test Speed

Adjusted mean values and standard errors (SE) were calculated for each of the CPCs stratified by vehicle class and closing speed. For 56 km/h (35 mph) crashtests, maximum deceleration values ranged from 36.6 (SE 1.07) g for minivans to 46.0 (SE 1.07) g for small SUVs. Time of maximum deceleration occurred earliest for small pickups at 38.2 (SE 3.22)ms after event onset, and latest for large passenger vehicles at 54.6 (SE 1.38) ms. The shortest pulse duration occurred in small SUVs at 90.8 (SE 1.36) ms and the longest pulses were in large SUVs at 112.9 (SE 2.10) ms. For maximum deceleration and pulse duration, no apparent pattern was observed for any vehicle class at any test speed. For onset rate, small pickups, large pickups, large SUVs, and midsize SUVs had the greatest onset rates across all test speeds. Adjusted mean estimates for all vehicle classes, test speeds, and CPCs are detailed in Appendix 1.

Coefficient of Change by Year

The coefficient of change in estimated mean CPC per vehicle generation start year was calculated and stratified by vehicle body type and closing speed (Appendix 2). Large passenger cars demonstrated the most consistent trends in coefficients across test speed; for 56 km/h (35 mph) tests, maximum deceleration increased (+0.96 g/year; p<0.0001), time of maximum deceleration was earlier (−1.33 ms/year; p=0.0002), pulse duration was shorter (−1.87 ms/year; p<0.0001), and change in velocity decreased (−0.16 km/h per year; p=0.0054). Similar trends were observed for 40 km/h (25 mph) and 48 km/h (30 mph) tests, although the decrease in pulse duration for 40 km/h tests was not significant. Midsize passenger cars tested at 56 km/h had significant increases in peak deceleration (+0.40 g/year; p=0.04), and decreases in pulse duration (−0.74 ms/year; p=0.0022) and delta-V (−0.12 km/h per year; p=0.0211), however CPC trends for 40 and 48 km/h tests were not consistent. Large SUVs tested at 56 km/h also exhibited significant increases in maximum deceleration (+1.57 g/year; p=0.0002), and decreases in time of peak (−2.88 ms/year; p=0.0002) and pulse duration (−2.51 ms/year; p=0.0017); these trends were consistent for 48 km/h tests, but were not consistent for 40 km/h tests, likely due to small sample size for the 40 km/h tests. Although small passenger cars and midsize SUVs had large numbers of vehicles tested, the coefficients of change for all CPCs were rarely significant, and did not necessarily show a consistent increase or decrease across all test speeds.

Statistically meaningful linear trends in CPC values are summarized in Table 2 below. The directionality of the arrow indicates either an increase or decrease in CPC coefficient per year, with the length and grey value of the arrows indicating the number of test speed categories (up to 3) for which this trend was true. As previously emphasized, the large passenger car group shows the most consistent trends, with statistically significant increases or decreases for all test speeds in each CPC excluding pulse duration. Of note, the CPC trends for some vehicles and test speeds showed conflicting statistically significant trends (e.g. maximum deceleration for large SUV shows that though two test speeds (48 and 56 km/h) displayed an increase in g/year, the remaining test speed (40 km/h) had a decrease in g/year); this inconsistency is likely due to the difference in population size at each test speed within the same vehicle class. If no arrow is present, no statistical significance was achieved for the vehicle class and CPC at any of the included test speeds. This table summarizes only the number of statistically significant values, and does not attempt to capture the magnitude of statistically meaningful changes; for exact values please refer to Appendix 2.

Table 2.

Significant trends for the effect of year on CPCs. Small light grey arrow indicates statistically significant increase/decrease for one of three test speeds (40 km/h, 48 km/h, or 56 km/h), medium-sized dark grey arrow indicates statistically significant change for two of three test speeds, and large black arrow indicates significance for all three test speeds. Arrows in multiple directions indicate conflicting directional trends associated with vehicle generation start year among test speed groups.

| Max Decel (g) | Time of Max (ms) | Onset Rate (g/s) | Pulse Duration (ms) | Delta-V (km/h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Passenger Car |

|

|

|||

| Midsize Passenger Car |

|

|

|

|

|

| Large Passenger Car |

|

|

|

|

|

| Small SUV |

|

|

|

||

| Midsize SUV |

|

|

|||

| Large SUV |

|

|

|

|

|

| Small Pickup |

|

||||

| Large Pickup |

|

|

|

|

|

| Minivan |

|

|

|

|

Overall, for most vehicle body types and test speeds, maximum deceleration values increased with each year, and pulse duration and change in velocity decreased. Time of maximum deceleration and onset rate did not show a consistent trend of increase or decrease across vehicle body types or test speeds.

Coefficient of change for vehicle weight

Small, midsize, and large passenger cars, small and large pickups, and minivans all showed a significant increase in test weight for each vehicle generation start year, ranging from a 10.6 kg/year increase (midsize passenger cars) to a 38.1 kg/year increase (large pickups). The SUV class did not show a consistent trend: large SUVs had a significant decrease in test weight (−25.3 kg/year; p=0.0005), midsize SUVs had a non-significant decrease in test weight each year, and small SUVs had a non-significant increase. Based on these results, for example, a 5 year increase in vehicle generation start year for a midsize passenger vehicle would result in an increase of 105.6 kg in test weight.

Change in Range of CPC Values by Year

Mean estimated CPC values were examined byvehicle generation start year and vehicle body type for each test speed. Vehicle generation start year was divided into consecutive 2 or 3 year periods.

Figure 3 shows the maximum deceleration values for the 56 km/h tests. Consistent with our findings of coefficient of change by year described above, the maximum deceleration increases from the 1997–1999 group to the 2009–2010 group for all vehicle classes except small passenger cars. Of note, the range (maximum-minimum) in mean deceleration values across all vehicle body types was greater in the 1997–1999 group than the in 2009–2010 group: (range = 17.1g in 1997–1999 vs. 10.7g in 2009–2010). The range in maximum deceleration values also decreased for 40 km/h and 48 km/h tests (40 km/h: range = 24.4 g in 1997–1999 vs. 5.22 g in 2009–2010; 48 km/h: range = 28.3 g in 1997–1999 vs. 10.4 g in 2009–2010). These results suggest a convergence of CPC’s over time, i.e., a trend toward crash pulse homogenization.

Figure 3:

Maximum deceleration by vehicle body type for 56 km/h (35 mph) full-frontal barrier tests.

Similarly, we observed homogenization in time of maximum deceleration (range = 41.1 ms in 1997–1999 vs. 10.2 ms in 2009–2010) (Figure 4) as vehicle generation year increased. Homogenization was also evident for pulse duration (range = 39.5 ms in 1997–1999 vs. 13.5 ms in 2009–2010) (Figure 5). For both time of maximum deceleration and pulse duration, this trend of homogenization of CPCs was also observed in both 40 km/h and 48 km/h tests.

Figure 4:

Time of maximum deceleration by vehicle body type for 56 km/h (35 mph) full-frontal barrier tests.

Figure 5:

Pulse duration by vehicle body type for 56 km/h (35 mph) full-frontal barrier tests.

DISCUSSION

Full-frontal rigid barrier impact tests from the NHTSA and TC databases were analyzed to determine time trends in adjusted mean CPCs stratified by vehicle class and test speed. This large-scale analysis included crash tests from multiple data sources with a wide variety of test speeds and vehicle types in order to support a comprehensive examination of the modern North American vehicle fleet. Time trends of CPCs were examined by vehicle generation start year rather than by actual model year in an attempt to quantify how the evolution of vehicle structure affected the crash pulse. This study adds value to the literature as a contemporary report of vehicle compartment acceleration trends over the past decade.

CPCs by Vehicle Class and Test Speed

One aspect of our study was to quantify adjusted mean CPC values by vehicle class and test speed parameters. Previously, Glass (2002) quantified average peak deceleration, average change in velocity, and average time duration values for cars, SUVs, trucks, and vans at 48 km/h (30 mph) and 56 km/h (35 mph) for a limited data set of FMVSS 208 and NCAP tests. Glass’s reported average peak decelerations were less than those values calculated in our study for all comparable vehicle classes at both crash speeds, and his durations were longer (e.g. peak deceleration of 34.6 g and pulse durations of 117 ms for passenger cars in 56 km/h tests vs. peak decelerations of 43.5 g, 40.6 g, and 38.1 g and durations of 91.3 ms, 98.7 ms, and 105.7 ms respectively for our small, midsize, and large passenger cars in 56 km/h tests). The point-by-point time averaging method used by Glass to summarize the pulses of all vehicles of the same class and test speed may not be the best way to quantify average pulse characteristics, as reduction in peak magnitudes are inevitable with even a slight peak time mismatch. This method yields an average curve that is less severe than almost any individual vehicle acceleration curve. In contrast, the method presented in this paper more accurately represents crash pulse characteristics because CPC values were calculated for each individual accelerometer signal prior to any any attempt to combine and summarize multiple signals, allowing for the accurate capture of peak deceleration and time of peak for each vehicle. Additional difference between results may be due to dissimilarity of vehicle model years included, as our study examined model years 2000–2010 while Glass was limited to 1995–2000.

CPC Change Over Time

Change in CPCs over time was determined by stratifying tests by vehicle class and test speed, and calculating the average linear change for each generation start year. Increase in maximum deceleration per year and decrease in pulse duration per year were the most consistent trends amongst all vehicle classes; large passenger cars, large SUVs, and minivans showed a statistically significant increase in peak deceleration and decreases in pulse duration for at least two of the three test speeds. Some statistically significant decreases in peak deceleration or increases in pulse durations did occur. However, those vehicle class/test speed combinations often had a small sample size (Appendix 2), resulting in weak statistical significance. Time of maximum deceleration was found to be significantly sooner each year for large passenger cars; midsize passenger cars, large SUVs, and minivans also had a shorter time of maximum each year to a lesser extent. Greater peak decelerations happening earlier in the event and shorter overall pulse duration suggests that these vehicles structures are becoming stiffer over time. In contrast, small passenger cars, small SUVs, and midsize SUVs have decreasing onset rates per year, implying that those vehicle classes may be becoming softer over time. However, these changes in onset rates were not statistically significant.

The stiffness of the front of a vehicle is a major contributing factor to crash pulse duration, magnitude and shape. In 1999, Park et al. reviewed 175 light trucks, vans, and SUVs U.S. NCAP tests encompassing model years 1983–1998. Vehicles were divided into model year groups 1983–1991, 1992–1995, and 1996–1998. Over the 14 years of included vehicles, Park found a non-significant decrease in average vehicle stiffness for the first 200 mm of crush over time (approximately 2.21 N/m for vehicle model years 1983–1991 vs. 1.96 N/m in 1996–1998 model years). In 2003, Swanson et al. expanded on Park’s research, characterizing the vehicle stiffness of 389 passenger cars of model years 1982–2001 in 56 km/h full-frontal rigid barrier crashes. Swanson characterized stiffness in three ways: “initial stiffness”, that is, the stiffness as determined from the force-deflection profiles, “static stiffness” which used only post-crash crush measurements, and “dynamic stiffness”, which utilizes dynamic displacement values calculated by double-integrating data from the vehicle-mounted accelerometers. Passenger cars demonstrated an increase for all three calculated stiffness parameters (32%, 62%, and 34% increases, respectively) over the 20 years of NCAP testing. When the vehicle population was further broken down into light, compact, medium, and heavy classes based on curb weight, the increasing stiffness trend was significant for nearly all classes. The largest stiffness increase occurred in the mid-to-late 90’s, between the final two year groupings (1994–1997 and 1998–2001). These passenger vehicle trends differ from the LTVs, which showed a non-significant decrease in stiffness over time. Of note, LTVs were generally much stiffer than passenger cars. Although stiffness calculations were not included as part of our study, the trends in stiffness found by Swanson et al. are similar to the trends we observed in CPCs, where higher occupant compartment accelerations and shorter pulse durations likely correspond to increased stiffness in vehicle structure.

Homogenization of CPCs

When examining the trends of crash pulse data by generation year, we found a reduction in the range of CPC values across widely different vehicle classes in newer vehicle generations as compared to vehicles designed and produced in the 90’s and early 00’s. Maximum deceleration, time of maximum deceleration, onset rate, and pulse duration were all more similar to one another across vehicle classes in the 2009–2010 generation year range. This homogenization was present across all tests speeds. This is a novel finding not previously reported in the literature to the best of our knowledge. Similar crash pulse characteristics between different vehicle body types may in the future lead to more universal design and application of safety systems across the vehicle fleet.

Implications for Real-World Application

Several researchers (Gearhart 2001, Varat 2003, Cao 2004, Gu 2005, Cheng 2006, Kral 2006, Warner 2007) have worked to create a numerical optimization of an “ideal” crash pulse, which is defined as the vehicle motion that yields the lowest maximum deceleration values for the occupant head and chest during a frontal impact. Crash pulse models are useful for determining effects of varying maximum deceleration, time duration, delta-V, and pulse shape on simulated occupant responses. Grimes and Lee (2000) created several crash pulse estimations based on a single 48 km/h (30 mph) vehicle-to-barrier crash, employing simple wave pulses for a variety of durations but maintaining the same delta-V value. They found that both crash pulse shape and duration affected the position and velocity time-histories of the occupant, with duration particularly critical to the accurate simulation of occupant motion. Crash pulse models that seek to optimize occupant safety in the vehicle may benefit from the data presented herein, as it presents a wide variety of vehicle class and speed conditions for newer vehicles. Incorporating this data into modeling may result in a more accurate prediction of occupant movement for the current fleet.

In 2009, Esfahani and Digges reviewed NASS-CDS frontal collisions involving vehicles of model year 1993–2006. Risk of MAIS2+ injury in occupants aged 16–50 years old was calculated for vehicle model year groups 1993–1999 and 2000–2006. For the 1993–1999 model year vehicles, belted front seat occupants had an injury risk of 7.8 percent, while rear-seated belted occupants had an injury risk of only 1.6 percent, demonstrating a statistically significant (p<.0001) protective benefit for the rear seat. For vehicle model years 2000–2006, however, the injury risk for front-seated occupants decreased to 6.3 percent and the rear-seated occupant injury risk increased to 5.1 percent. Of note, the rear seat no longer had a statistically significant protective benefit (p=0.6) for belted occupants. Esfahani and Digges suggested the difference was due to the more aggressive crash pulse in the newer vehicles, resulting in a higher reliance on vehicle restraint systems to protect occupants. Their findings are similar to a study performed by Kuppa et al. in 2005, which examined ATD responses in the front and rear seating environments, and found that restrained adult ATDs in the rear seat experience higher injury metrics than the same-sized dummies seated in the driver and front passenger seats. These studies emphasize the need for increased occupant protection in the rear seats of vehicles, especially because it is the recommended seating position of children under the age of 12 (Durbin, 2011).

Limitations

Although these data provide a comprehensive analysis of vehicles that have been tested by NHTSA and TC within the last decade, the frequency of a particular type of vehicle in the database is not necessarily representative of its frequency in the vehicle fleet or, more importantly, frequency of crash involvement. Vehicle sales and current ownership may skew the fleet towards a specific type of vehicle class, which may subsequently affect the number of crashes between specific vehicle types. Future work may include weighting CPCs based on the numbers of each vehicle class currently registered in North America, and/or assessing current trends in vehicle sales. Additionally, full-frontal barrier-type impacts are not common crashes in the field. More work needs to be done in order to quantify crash pulse characteristics for overlap and vehicle-to-vehicle collisions, both of which have application to real-world crash environments.

CONCLUSION

Vehicle crash pulse characteristics for 2000–2010 model year frontal rigid-barrier tests showed an overall increasing trend in maximum deceleration and a decrease in pulse duration by generation year for most vehicle classes. This shorter, more severe pulse is consistent with a stiffening vehicle structure suggested in the literature for the current vehicles present within the fleet. Simultaneously, crash pulse characteristics are becoming more homogeneous for disparate vehicle classes, which may reduce the required number of unique safety system designs in the fleet and thus lower vehicle safety system cost to the consumer. This research has implications for vehicle manufacturers, as it provides an updated summary of physical vehicle crash environments that may aid occupant simulations and validations for restraint systems developed for future vehicles.

Acknowledgments

The study team would like to acknowledge the National Science Foundation (NSF)Center for Child Injury Prevention Studies at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) for sponsoring this study and its Industry Advisory Board (IAB) for their support, valuable input and advice. The views presented are those of the authors and not necessarily the views of CHOP, the NS For the IAB members.

The authors would like to thank Suzanne Tylko and the Government of Canada for providing crash data used in this analysis.

We would also like to thank the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) and Highway Loss Data Institute (HLDI) for their aid in reclassifying our numerous vehicles using their comprehensive standards, and Gregory S. Anderson of Scalia Safety Engineering for generously providing his Sisters and Clones database necessary for the analysis by vehicle generation.

COMMONLY USED ABBREVIATIONS

- ATD

Anthropomorphic Test Device

- CFC

Channel Frequency Class

- CPC

Crash Pulse Characteristics

- FMVSS

Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard

- HLDI

Highway Loss Data Institute

- LTV

Light Transit Vehicle

- MAIS

Maximum Abbreviated Injury Score

- NCAP

New Car Assessment Program

- NHTSA

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

- TC

Transport Canada

APPENDIX

Appendix 1:

Adjusted mean and standard error (SE) for CPCs by vehicle class and target closing speed, controlling for accelerometer location and test performer.

| N signals | N vehicles | Max Deceleration (g) | SE | Time of Max (ms) | SE | Onset Rate (g/s) | SE | Pulse Duration (ms) | SE | Delta-V (km/h) | SE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Passenger Car | 40 km/h | 164 | 64 | 32.6 | 0.78 | 47.1 | 1.32 | 767.8 | 45.81 | 92.7 | 1.39 | 45.2 | 0.15 |

| 48 km/h | 300 | 104 | 37.8 | 0.66 | 48.3 | 1.06 | 939.9 | 83.39 | 94.1 | 0.88 | 54.4 | 0.22 | |

| 56 km/h | 319 | 130 | 43.5 | 0.63 | 47.5 | 0.83 | 992.0 | 34.39 | 91.3 | 0.75 | 64.0 | 0.19 | |

| Midsize Passenger Car | 40 km/h | 89 | 37 | 30.5 | 0.88 | 48.7 | 1.60 | 667.5 | 28.47 | 95.4 | 1.46 | 45.6 | 0.30 |

| 48 km/h | 210 | 74 | 37.9 | 0.98 | 50.8 | 1.08 | 803.7 | 35.22 | 98.3 | 1.21 | 54.2 | 0.20 | |

| 56 km/h | 314 | 130 | 40.6 | 0.72 | 51.5 | 1.07 | 882.1 | 37.70 | 98.7 | 1.00 | 64.2 | 0.20 | |

| Large Passenger Car | 40 km/h | 25 | 11 | 27.5 | 0.55 | 50.2 | 3.06 | 666.6 | 59.30 | 103.7 | 3.60 | 45.0 | 0.25 |

| 48 km/h | 100 | 35 | 35.6 | 1.09 | 50.1 | 2.06 | 826.4 | 56.45 | 99.6 | 1.25 | 54.1 | 0.20 | |

| 56 km/h | 145 | 57 | 38.1 | 1.10 | 54.6 | 1.38 | 776.3 | 41.89 | 105.7 | 1.56 | 64.5 | 0.28 | |

| Small SUV | 40 km/h | 26 | 12 | 32.3 | 0.94 | 51.7 | 3.67 | 714.2 | 83.02 | 87.0 | 1.76 | 44.3 | 0.23 |

| 48 km/h | 78 | 28 | 40.1 | 1.52 | 47.9 | 1.59 | 904.1 | 75.09 | 91.8 | 1.50 | 54.3 | 0.64 | |

| 56 km/h | 89 | 37 | 46.0 | 1.07 | 42.7 | 1.13 | 1126.2 | 40.69 | 90.8 | 1.36 | 64.2 | 0.50 | |

| Midsize SUV | 40 km/h | 34 | 16 | 34.0 | 0.96 | 40.8 | 3.42 | 1086.0 | 158.90 | 91.8 | 3.85 | 45.4 | 0.60 |

| 48 km/h | 124 | 42 | 38.5 | 1.19 | 44.3 | 2.46 | 1302.5 | 184.85 | 94.8 | 1.13 | 53.4 | 0.30 | |

| 56 km/h | 221 | 100 | 43.9 | 0.64 | 44.0 | 1.21 | 1219.0 | 84.78 | 98.0 | 1.45 | 63.9 | 0.24 | |

| Large SUV | 40 km/h | 8 | 4 | 25.7 | 0.36 | 42.1 | 0.60 | 765.3 | 71.31 | 108.2 | 3.48 | 44.0 | 0.13 |

| 48 km/h | 40 | 13 | 35.6 | 2.52 | 44.2 | 4.85 | 1281.8 | 422.99 | 108.3 | 3.40 | 54.2 | 0.65 | |

| 56 km/h | 61 | 26 | 40.0 | 1.38 | 51.9 | 3.29 | 1361.5 | 322.30 | 112.9 | 2.10 | 63.7 | 0.56 | |

| Small Pickup | 40 km/h | 1 | 1 | 32.3 | 19.4 | 1663.5 | 95.2 | 42.9 | |||||

| 48 km/h | 20 | 7 | 41.0 | 2.60 | 34.0 | 5.79 | 1597.8 | 369.20 | 100.4 | 4.17 | 52.3 | 0.63 | |

| 56 km/h | 47 | 20 | 42.7 | 1.21 | 38.2 | 3.22 | 1592.9 | 190.43 | 97.2 | 1.72 | 62.8 | 0.69 | |

| Large Pickup | 40 km/h | 25 | 11 | 36.2 | 2.75 | 43.6 | 1.86 | 1012.3 | 56.32 | 108.5 | 3.09 | 44.7 | 0.26 |

| 48 km/h | 31 | 11 | 37.6 | 1.55 | 34.8 | 4.63 | 1326.4 | 158.28 | 103.0 | 3.31 | 52.8 | 0.59 | |

| 56 km/h | 100 | 42 | 39.9 | 1.02 | 43.3 | 2.95 | 1230.2 | 131.09 | 109.3 | 2.36 | 63.9 | 0.36 | |

| Minivan | 40 km/h | 34 | 13 | 26.9 | 1.09 | 48.8 | 2.65 | 680.6 | 88.28 | 103.0 | 2.43 | 45.4 | 0.35 |

| 48 km/h | 81 | 29 | 30.7 | 0.85 | 47.5 | 1.73 | 725.3 | 40.97 | 110.7 | 2.37 | 54.5 | 0.17 | |

| 56 km/h | 109 | 40 | 36.6 | 1.07 | 50.5 | 2.12 | 849.6581 | 63.29 | 111.8 | 1.33 | 64.6 | 0.29 |

Appendix 2:

Linear change in CPC values by generation start year, controlling for accelerometer location and test performer. Statistically significant (p<0.05) values are bolded.

| N signals | N vehicles | Median Generation Start Year | Generation Start Year IQR | Generation Start Year Range | Max Decel (g) | p Value | Time of Max (ms) | p Value | Onset Rate (g/s) | p Value | Pulse Duration (ms) | p Value | Delta-V (km/h) | p Value | Vehicle Test Weight (kg) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Passenger Car | 40 km/h | 164 | 64 | 2007 | 5 years | 1998–2010 | 0.0061 | 0.9877 | −0.222 | 0.7281 | −0.1194 | 0.9966 | −0.0346 | 0.9425 | −0.0782 | 0.2304 | 10.6154 | 0.0001* |

| 48 km/h | 300 | 104 | 2004 | 7 years | 1997–2010 | −0.5011 | 0.0146* | 0.4029 | 0.2257 | −56.9094 | 0.0895 | 0.245 | 0.3187 | −0.0144 | 0.7976 | |||

| 56 km/h | 319 | 130 | 2004 | 6 years | 1998–2010 | 0.1784 | 0.4071 | 0.4509 | 0.0554 | −5.4902 | 0.662 | −0.4901 | 0.0302* | 0.0687 | 0.1506 | |||

| Midsize Passenger Car | 40 km/h | 89 | 37 | 2006 | 4 years | 1998–2008 | 0.0854 | 0.8091 | 0.5133 | 0.4504 | −11.6497 | 0.3171 | 0.7182 | 0.2575 | −0.0274 | 0.8089 | 10.5649 | <.0001* |

| 48 km/h | 210 | 74 | 2005 | 4 years | 1998–2010 | 0.4132 | 0.1742 | −0.9597 | 0.0028* | 24.7194 | 0.0378* | −0.5732 | 0.0991 | −0.1142 | 0.0334* | |||

| 56 km/h | 314 | 130 | 2003 | 6 years | 1997–2010 | 0.3974 | 0.04* | −0.4656 | 0.1679 | 33.7705 | 0.0256* | −0.7374 | 0.0022* | −0.1187 | 0.0211* | |||

| Large Passenger Car | 40 km/h | 25 | 11 | 2005 | 6 years | 2000–2009 | 0.9063 | <.0001* | −3.1533 | 0.0076* | 73.2144 | <.0001* | −0.1284 | 0.9159 | −0.3581 | 0.0061* | 14.4688 | <.0001* |

| 48 km/h | 100 | 35 | 2002 | 8 years | 1997–2010 | 0.7219 | 0.008* | −1.6812 | 0.001* | 43.9939 | 0.0001* | −1.5492 | <.0001* | −0.167 | 0.0012* | |||

| 56 km/h | 145 | 57 | 2000 | 5 years | 1997–2010 | 0.9605 | <.0001* | −1.3339 | 0.0002* | 48.2239 | 0.0019* | −1.8713 | <.0001* | −0.1592 | 0.0054* | |||

| Small SUV | 40 km/h | 26 | 12 | 2004 | 6 years | 2001–2009 | −0.4303 | 0.0357* | 0.7673 | 0.5639 | −17.666 | 0.5876 | 1.6588 | 0.0017* | 0.1131 | 0.3677 | 5.429 | 0.3859 |

| 48 km/h | 78 | 28 | 2002 | 4.75 years | 1999–2009 | −0.253 | 0.6451 | 0.667 | 0.3351 | −39.1623 | 0.3023 | 0.1313 | 0.7604 | −0.2298 | 0.2803 | |||

| 56 km/h | 89 | 37 | 2003 | 6 years | 1999–2009 | 0.6706 | 0.0715 | 1.0155 | 0.0042* | −7.3144 | 0.6332 | −0.2831 | 0.5521 | −0.0963 | 0.6584 | |||

| Midsize SUV | 40 km/h | 34 | 16 | 2004 | 5 years | 1998–2009 | −0.7332 | 0.0433* | 1.188 | 0.344 | −49.2403 | 0.4782 | 1.829 | 0.2651 | 0.3393 | 0.2134 | −6.258 | 0.1518 |

| 48 km/h | 124 | 42 | 2004 | 5 years | 1998–2010 | 0.357 | 0.2243 | 0.3024 | 0.6675 | −11.9868 | 0.7623 | −0.6034 | 0.0507 | −0.0271 | 0.788 | |||

| 56 km/h | 221 | 100 | 2003 | 5 years | 1997–2010 | 0.3158 | 0.0811 | 0.4582 | 0.0966 | −11.019 | 0.5188 | −0.6524 | 0.0101* | −0.0161 | 0.7957 | |||

| Large SUV | 40 km/h | 8 | 4 | 2004.5 | 2.5 years | 2000–2007 | −3.8022 | <.0001* | 11.6357 | <.0001* | −329.313 | <.0001* | 20.7571 | <.0001* | −0.4817 | <.0001* | −25.2726 | 0.0005* |

| 48 km/h | 40 | 13 | 2003 | 5 years | 2000–2009 | 2.1348 | <.0001* | −2.1124 | 0.1035 | 143.1467 | 0.1263 | −4.1983 | <.0001* | −0.627 | 0.005* | |||

| 56 km/h | 61 | 26 | 2002 | 6 years | 1997–2008 | 1.5731 | 0.0002* | −2.8805 | 0.0041* | 156.4934 | 0.0717 | −2.5068 | 0.0017* | −0.2113 | 0.2693 | |||

| Small Pickup | 40 km/h | 1 | 1 | 2005 | 0 years | 2005–2005 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 28.3351 | 0.0037* |

| 48 km/h | 20 | 7 | 2004 | 7 years | 1997–2005 | 0.138 | 0.8238 | 2.2559 | 0.1009 | −40.6937 | 0.6233 | −0.9478 | 0.3622 | 0.0373 | 0.7919 | |||

| 56 km/h | 47 | 20 | 1998 | 7 years | 1997–2005 | 0.0571 | 0.8626 | 0.4302 | 0.6277 | 19.6943 | 0.6944 | −1.815 | 0.0016* | −0.1744 | 0.3128 | |||

| Large Pickup | 40 km/h | 25 | 11 | 2005 | 7 years | 1997–2007 | 0.5105 | 0.5859 | 4.0507 | <.0001* | −68.0842 | <.0001* | 1.7763 | 0.0743 | −0.0493 | 0.2309 | 38.0657 | <.0001* |

| 48 km/h | 31 | 11 | 2002 | 6 years | 1997–2009 | −1.1907 | 0.0199* | −1.9453 | 0.0921 | 30.7564 | 0.3833 | 0.6113 | 0.6009 | 0.2241 | 0.1332 | |||

| 56 km/h | 100 | 42 | 2002 | 6 years | 1997–2009 | 0.5197 | 0.0415* | 0.8252 | 0.2753 | −18.9283 | 0.4652 | −1.5041 | 0.0112* | 0.0198 | 0.8278 | |||

| Minivan | 40 km/h | 34 | 13 | 2003 | 4 years | 1999–2009 | 0.9645 | 0.0318* | −3.3634 | 0.0021* | 72.7256 | 0.0313* | −2.0177 | 0.0643 | 0.1449 | 0.4041 | 12.2241 | 0.0011* |

| 48 km/h | 81 | 29 | 2004 | 6 years | 1997–2009 | 0.4536 | 0.0321* | −0.7327 | 0.0522 | 32.1487 | 0.0027* | −1.3431 | 0.0098* | 0.0591 | 0.2361 | |||

| 56 km/h | 109 | 40 | 2001 | 5 years | 1997–2010 | 0.3102 | 0.3168 | 0.0267 | 0.9675 | 7.6948 | 0.708 | −1.8134 | <.0001* | −0.1246 | 0.0581 |

REFERENCES

- Anderson GC. Vehicle Year & Model Interchange List (Sisters & Clones List) Scalia Safety Engineering; Madison, WI: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bendjellal F. Child Protection in Cars—Advances & Key Challenges. Proc 2007 International Research Council on the Biomechanics of Injury; Maastricht, The Netherlands. September 19–21, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cao JZ, Koka MR, Law SE. Vehicle Pulse Shape Optimization to Improve Occupant Response in Front Impact. 2004 SAE World Congress; Detroit, MI. March 8–11, 2004; Paper No. 2004-01-1625. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z. Optimal Crash Pulse for Minimization of Peak Occupant Deceleration in Frontal Impact. 2006 SAE World Congress; Detroit, MI. April 3–8, 2006; Paper No. 2006-01-0670. [Google Scholar]

- Durbin DR. Child Passenger Safety. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):788–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esfahani ES, Digges K. Trend of Rear Occupant Protection in Frontal Crashes over Model Years of Vehicles. 2009 SAE World Congress & Exhibition; Detroit, MI. April, 2009; Paper No. 2009-01-0377. [Google Scholar]

- Gearhart C. Recent Progress in Crash Pulse Analysis. Int. J. of Vehicle Design (Special Issue) 2001;26(4):395–406. [Google Scholar]

- Glass W. Technical Report on the FMVSS 213 Crash Pulse and Test Bench Analysis. Apr, 2002. Docket No. NHTSA-02-11707-9.

- Grimes WD, Lee FD. The Effect of Crash Pulse Shape on Occupant Simulations. 2000 SAE World Congress; Detroit, MI. March 6–9, 2000; Paper No. 2000-01-0460. [Google Scholar]

- Kral J. Yet Another Look at Crash Pulse Analysis. 2006 SAE World Congress; Detroit, MI. April 3–6, 2006; Paper No. 2006-01-0958. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppa S, Saunders J, Fessahaie O. Rear Seat Occupant Protection in Frontal Crashes. Proc 19th Enhanced Safety of Vehicles Conference; Washington, DC. June 6–9, 2005; Paper No. 05-0212. [Google Scholar]

- Linder A, Avery M, Krafft M, Kullgren A. Change of Velocity and Pulse Characteristics in Rear Impacts: Real World and Vehicle Tests Data. Proc 18th Enhanced Safety of Vehicles Conference; Nagoya, Japan. 2003. Paper No. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Highway Loss Data Institute (HLDI) Fatality Facts 2009: Occupants of Cars, Pickups, SUVs, and Vans. Available at: http://www.iihs.org/research/fatality_facts_2009/occupants.html.

- Park BT, Hackney JR, Morgan RM, Chan H, Lowrie JC, Devlin HE. The New Car Assessment Program: Has It Led to Stiffer Light Trucks and Vans Over the Years?. 1999 SAE International Congress & Exposition; Detroit, MI. March 1–4, 1999; Paper No. 1999-01-0064. [Google Scholar]

- Society of Automotive Engineers SAE J211/1 - Instrumentation for Impact Tests – Part I – Electronic Instrumentation. Mar, 1995.

- Swanson J, Rockwell T, Beuse N, Summers L, Summers S, Park B. Evaluation of Stiffness Measures from the U.S. New Car Assessment Program. Proc 18th Enhanced Safety of Vehicles Conference; Nagoya, Japan. 2003; Paper No. 527. [Google Scholar]

- Varat MS, Husher SE. Crash Pulse Modeling for Vehicle Safety Research. Proc 18th Enhanced Safety of Vehicles Conference; Nagoya, Japan. 2003. Paper No. 501. [Google Scholar]

- Warner CY, Warner MH, Crosby CL, Armstrong MJ. Pulse Shape and Duration in Frontal Crashes. 2007 SAE World Congress; Detroit MI. April 16–19, 2007; Paper No. 2007-01-0724. [Google Scholar]