Abstract

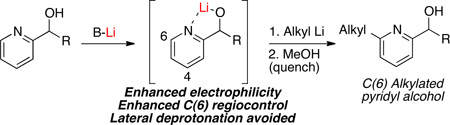

Direct C(6) alkylation of pyridyl alcohols can be achieved following an initial deprotonation of the hydroxy group. This transformation, which is believed to occur by a Chichibabin-type alkylation, avoids lateral deprotonation prior to pyridine ring alkylation and gives increased regioselectivity for C(6) over C(4) alkylation.

The pyridine heterocycle has emerged as an important structural motif in complex natural products,1a–c pharmaceuticals1d–e and in designer ligands for catalysis.2 The efficient preparation and study of pyridine-containing molecules depends on general and direct methods for the functionalization of pyridines and their corresponding picoline derivatives. Not surprisingly, numerous approaches have been established for the direct C(2) and C(6) functionalization of the pyridine nucleus,3 which include the introduction of heteroatoms (e.g., the Chichibabin reaction),4 as well as the installation of halogens and carbon substituents (e.g., using deprotonation/functionalization or the Minisci process).5,6 However, several unmet challenges are inherent in the direct C(6) functionalization of picoline derivatives (e.g., A, Figure 1).7 These challenges include competing functionalization at C(4) (e.g., via C), as well as lateral functionalization of the picoline group. This latter competing process, which may be initiated by deprotonation of the pseudo-benzylic position (see E),7g,h plagues many attempts to directly functionalize picoline derivatives. In many cases, competing deprotonation leads to a lack of productive reactivity (e.g., via E) or decomposition (e.g., via D).7a,e,f

Figure 1.

Challenges with direct C(6) functionalization of picoline derivatives by alkyl nucleophile addition

Recently, a series of metal-mediated approaches to achieve C(6) functionalization of picolines has been introduced, which addresses many of the functional group and regioselectivity challenges inherent in traditional methodologies for pyridine functionalization.8,9 However, the direct C(6) alkylation of hydroxylated variants of picoline derivatives (pyridyl alcohols) remains unsolved. In this manuscript, we describe a solution to this challenge that relies on a Chichibabin-type alkylation.

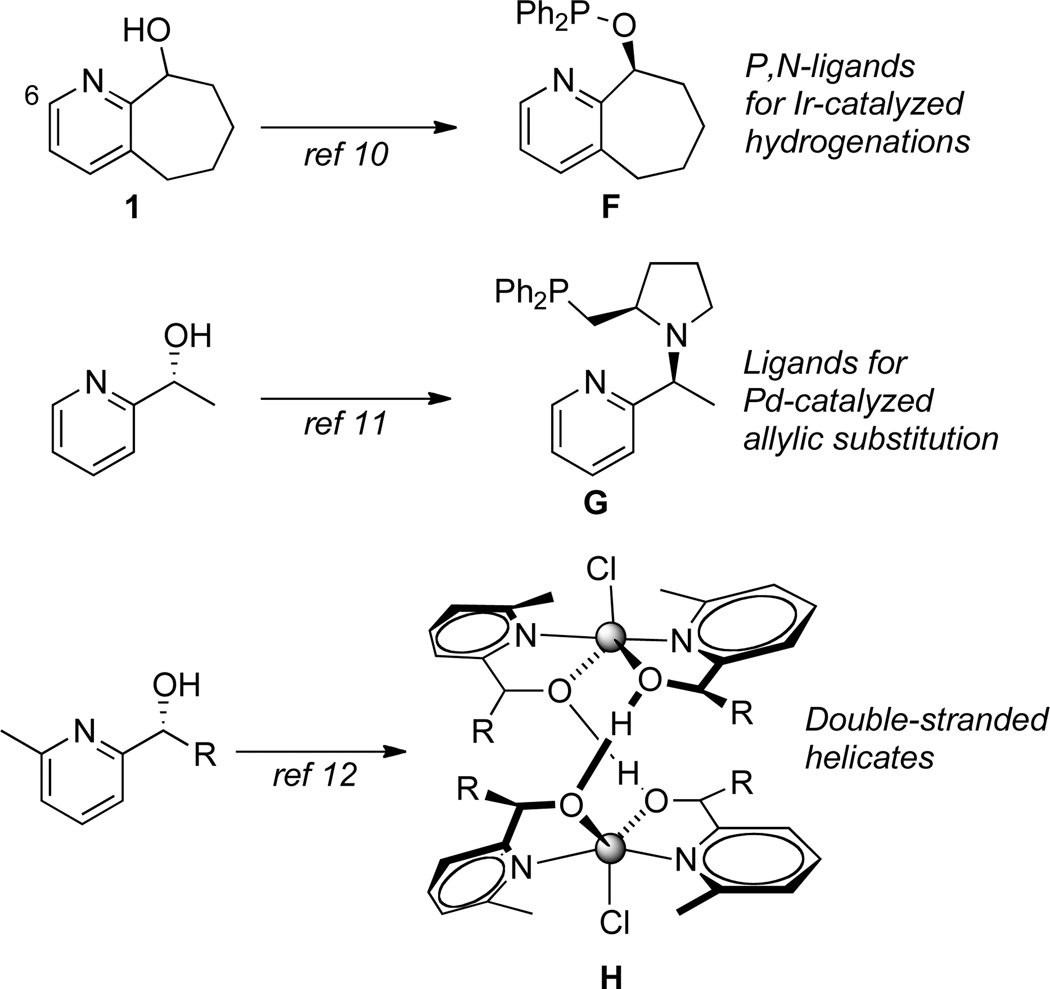

Pyridyl alcohols (e.g., 1, Figure 2) represent a unique class of picoline derivatives, which has proven broadly useful in the synthesis of ligands for the enantioselective hydrogenation of unactivated olefins (e.g., F, Figure 2)10 or for Pd-catalyzed allylic substitution reactions (e.g., G).11 Additionally, pyridyl alcohols have been found to self assemble in the presence of certain metal salts to form double-stranded helicates (e.g., H).12 As such, methods that provide direct access to alkylated variants of pyridyl alcohols would be highly valuable. An attractive option to achieve the direct alkylation of pyridyl alcohols would be to employ an alkylative variant of the Chichibabin reaction, which has been previously used in the direct alkylation of pyridines.7

Figure 2.

Examples of pyridyl alcohol utility

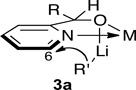

For example, during investigations on the reactivity of indolizinones,13 we required efficient access to an alkylated variant of pyridyl alcohol 1 (Figure 2). After extensively investigating various methods for the introduction of a butyl group at C(6) of 1, it was determined that only the direct, Chichibabin-type reaction with n-BuLi furnished the desired product. We postulated that pyridyl alcohols could offer a general solution to the traditional challenges associated with an alkylative Chichibabin-type process. First, by deprotonation of the alcohol group (e.g., in 2, Scheme 1) with an appropriate base, an alkoxide intermediate would be formed (see 3), which would be slow to undergo lateral deprotonation (e.g., upon treatment with an alkyl lithium reagent). Second, a potential interaction between the alkoxide counter-cation (M) and the pyridine nitrogen of 3 would enhance the electrophilicity at C(6) and also increase the basicity of the alkoxide lone pairs. This potential increase in basicity of the alkoxide was expected to enhance interactions with organometals (see 3a), which would in turn increase the nucleophilicity of the organometallic toward the pyridine nucleus and also direct its delivery to the proximal C(6) position of 3 (in preference to C(4)).14 Finally, loss of LiH and protonation would provide the desired C(6)-alkylated pyridyl alcohol (5).15

Scheme 1.

Proposed facilitation of Chichibabin-type alkylation of pyridyl alcohols (2)

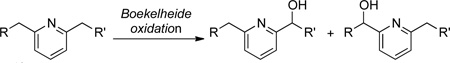

To test this hypothesis, we initiated our studies on the direct alkylation of pyridyl alcohols with 1 (see Table 1), which was prepared from commercially available 2,3-cycloheptenopyridine using a Boekelheide oxidation sequence.10a Pyridyl alcohol 1 was treated sequentially with a range of bases followed by n-BuLi as the alkyl nucleophile. Thus, using n-BuLi as the base (23 °C, 0.5 h), followed by an additional 1.1 equivalents of n-BuLi as the nucleophile, and stirring at 23 °C for 44 h resulted in 65% conversion to 6 after quenching (with MeOH) and a standard workup (entry 1). Increasing the temperature to 60 °C (entry 2) led to 6 in essentially the same conversion but in a shorter reaction time period (24 h). Upon heating the reaction mixture to 110 °C (entry 3), conversion to 6 (71%) was also observed, along with some byproducts. Interestingly, employing NaH (entry 4) as the base resulted in only 10% conversion, whereas the use of EtMgBr (entry 5) or n-BuMgCl (entry 6) as base did not lead to productive reaction and resulted in the recovery of the starting material.

Table 1.

Optimization of the direct alkylation of 1

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | base | conditionsa | conversion (%)b |

| 1 | n-BuLi | 23 °C, 44 h | 65 |

| 2 | n-BuLi | 60 °C, 24 h | 67 |

| 3 | n-BuLi | 110 °C, 24 h | 71 |

| 4 | NaH | 110 °C, 24 h | 10 |

| 5 | EtMgBrc | 110 °C, 24 h | 0 |

| 6 | n-BuMgClc | 110 °C, 24 h | 0 |

All reactions were performed in PhMe in a Schlenk tube under a N2 atmosphere.

Determined by 1H NMR.

Alkylmagnesium halides were insoluble under the reaction conditions.

The optimal reaction conditions (outlined in Table 1, entry 3) were applied to a range of substrates as illustrated in Figure 3 (see 7–14; only products are shown). Notably, in the absence of the hydroxy group, polymerization or decomposition was observed for the majority of substrates (e.g., 7a or 11a), suggesting an important role for the hydroxy group.16 Acyclic pyridyl alcohols gave modest to good isolated yields of the alkylated products (see 7b; 8–12). For cyclic pyridyl alcohols, only the 7- and 8-membered ring substrates gave satisfactory yields of the alkylated products (compare 13 to 14–17). Primary and secondary alkyl lithium reagents were competent nucleophiles (e.g., see 14 and 15, respectively), whereas tertiary alkyl lithiums (see 16) and aryl lithium nucleophiles (see 18) led to reduced yields of the adducts (in the latter case, presumably due to competing lithiation of the newly introduced benzene ring).7b

Figure 3.

Products of the direct alkylation of selected pyridyl alcohols. as-BuLi was used as the base; bt-BuLi was used as the base; cMeLi was used as the base; dPhLi was used as the base.

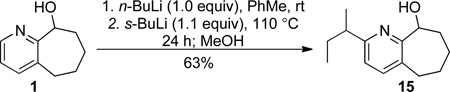

To better understand the mechanism and explore the scope of these direct alkylation processes, a series of experiments, as outlined in Eq 1–4, was undertaken. Pyridyl alcohol 1 was treated with n-BuLi (1.0 equiv), followed by s-BuLi (1.1 equiv) as the nucleophile. The product, containing a s-butyl group at C(6) (15, Eq 1), was isolated in 63% yield, which suggests that, in principle, only 1.0 equivalent of the nucleophile is required. Therefore, for cases where a precious alkyl substituent is required, n-BuLi could be employed as the sacrificial base.

|

(1) |

When methyl ether 19 (Eq 2)17 was subjected to the alkylation conditions, only a trace amount (2%) of the n-butylated product (20) was obtained, with the remainder of the mass balance accounted for by unreacted 19 and a complex mixture of unidentified byproducts. This observation suggests that the deprotonation of the hydroxy group is crucial for alkylation. Replacing the oxygen atom of 19 with nitrogen (see methylamine 21, Eq 3) led to a 15% yield of the C(6)-alkylated product (see 22, Eq 3).18 This observation further emphasizes the seemingly special role of the proximal alkoxide as compared to an amido group.

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

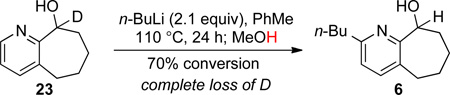

When deuterated substrate 23 (Eq 4)17 was subjected to the alkylation conditions, analysis of the resulting product (i.e., 6) revealed complete replacement of the pseudobenzylic deuterium by proton. This result is contrary to our prediction that the carbinol proton is protected from deprotonation (see 3, Figure 1). However, the facility of the alkylation reaction (i.e., conversion of 23 to 6) suggests that deprotonation of the carbinol center, or of the newly introduced pseudobenzylic position, may occur following alkylation (perhaps by the generated LiH). Support for this hypothesis was obtained by performing the alkylation reaction of 23 in deuterated toluene, followed by quenching with deuterated methanol. Analysis of the resulting product showed the presence of deuterium at both pseudobenzylic positions of 6, i.e., at the carbinol center and at the pseudobenzylic position of the n-butyl chain.

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

In conclusion, the direct alkylation of pyridyl alcohols using alkyl lithium reagents has been accomplished. The reaction is thought to proceed via the intermediacy of a lithium alkoxide intermediate, which enhances the C(6)-alkylation of the pyridine ring. Despite the modest yield of these direct functionalization reactions, they represent an effective one step alternative to multistep methods that have been previously employed for the synthesis of the target compounds.10a,c

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Alison Narayan (University of Michigan) for initial studies on these alkylation reactions and for insightful discussions. This work was supported by a grant from the NIH (NIGMS R01 084906). RS is a Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar. JLJ is grateful to the NSF for a graduate fellowship.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental details and copies of 1H and 13C spectra for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Holliday BJ, Mirkin CA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:2022–2043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Michael JP. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2005;22:627–646. doi: 10.1039/b413750g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bagley MC, Glover C, Merritt EA. Synlett. 2007:2459–2482. [Google Scholar]; (d) Henry GD. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:6043–6061. [Google Scholar]; (e) Uenishi J, Takagi T, Ueno T, Hiraoka T, Yonemitsu O, Tsukube H. Synlett. 1999:41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Conti S, Falorni M, Giacomelli G, Soccolini F. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:8993–9000. [Google Scholar]; (b) Felluga F, Baratta W, Fanfoni L, Pitacco G, Rigo P, Benedetti F. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:3547–3550. doi: 10.1021/jo900271x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lyle MPA, Narine AA, Wilson PD. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:5060–5064. doi: 10.1021/jo0494275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zimmermann N, Keenan M, Hayashi M, Kaiser S, Goddard R, Pfaltz A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:70–74. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Liu Q-B, Yu C-B, Zhou Y-G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:4733–4736. [Google Scholar]; (f) Lobmaier GM, Frey GD, Dewhurts RD, Herdtweck E, Herrmann WA. Organometallics. 2007;26:6290–6299. [Google Scholar]; (g) Bianchini C, Giambastiani G, Luconi L, Meli A. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010;254:431–455. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Joule JA, Mills K. In: Heterocyclic Chemistry. 4th ed. Blackwell Publishing, editor. Oxford, U. K.: Blackwell Science Ltd.; 2000. p. 66. [Google Scholar]; (b) Abramovitch RA, Sacha JG. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 1966;6:229–345. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Chichibabin AE, Zeide OA. J. Russ. Phys. Chem. Soc. 1914;46:1216–1236. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chichibabin AE. Ber. 1923;56B:1879–1885. [Google Scholar]; (c) McGill CK, Rappa A. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 1988;44:1–79. [Google Scholar]

- 5.A recent review: Bull JA, Mousseau JJ, Pelletier G, Charette AB. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:2642–2713. doi: 10.1021/cr200251d.

- 6. Minisci F, Galli R, Malatesta V, Caronna T. Tetrahedron. 1970;26:4083–4091. Minisci F, Vismara E, Fontana F. Heterocycles. 1989;28:489–519. For a recent variant, see: Seiple IB, Su S, Rodriguez RA, Gianatassio R, Fujiwara Y, Sobel AL, Baran PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:13194–13196. doi: 10.1021/ja1066459.

- 7. Brown HC, Kanner B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966;88:986–992. Francis RF, Wisener JT, Paul JM. Chem. Commun. 1971:1420. Francis RF, Davis W, Wisener JT. J. Org. Chem. 1974;39:59–62. Epsztajn J, Bieniek A, Brzezinski JZ. Bull. Acad. Pol. Sci. Sér. Sci. biol. 1975;23:917–922. Rewcastle GW, Katritzky AR. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 1993;56:155–302. Campeau L-C, Fagnou K. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1058–1068. doi: 10.1039/b616082d. Epsztajn J, Bieniek A. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. I. 1985:213–219. Vedernikov AN, Pink M, Caulton KG. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:4806–4814. doi: 10.1021/jo034268v. For an alternative approach to C(6) functionalization using pyridine N-oxides see: Denmark SE, Fan Y. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2006;17:687–707.

- 8.Nakao Y. Synthesis. 2011:3209–3219. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Guan B-T, Hou Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18086–18089. doi: 10.1021/ja208129t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Berman AM, Lewis JC, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:14926–14927. doi: 10.1021/ja8059396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Larivée A, Mousseau JJ, Charette AB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:52–54. doi: 10.1021/ja710073n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Cho SH, Hwang SJ, Chang S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9254–9256. doi: 10.1021/ja8026295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Campeau L-C, Rousseaux S, Fagnou K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:18020–18021. doi: 10.1021/ja056800x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Murakami M, Hori S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4720–4721. doi: 10.1021/ja029829z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Kaiser S, Smidt SP, Pfaltz A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;31:5194–5197. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Roseblade SJ, Pfaltz A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:1402–1411. doi: 10.1021/ar700113g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Woodmansee DH, Müller M-A, Neuburger M, Pfaltz A. Chem. Sci. 2010;1:72–78. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uenishi J, Hamada M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2001;12:2999–3006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Telfer SG, Sato T, Kuroda R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:581–584. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Telfer SG, Kuroda R. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:57–68. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardin Narayan AR, Sarpong R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:70–78. doi: 10.1039/c1ob06423a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

14.A 3-dimensional depiction of 3a reveals a potential proximity-guided addition of R’Li to C(6).

-

15.This method is especially attractive if one considers the alternative Boekelheide oxidation of substrates where R and R’ are similar, which is likely to be non-selective:

- 16.It has been reported (ref 7b, c) that in the presence of an excess of t-butyl lithium, pyridine gives a mixture of alkylated products, including 2,4,6-tri-t-butylpyridine (33% yield in refluxing hexane and 76% yield in refluxing heptane).

- 17.For details on the preparation of 19, 21 and 23, see the Supporting Information.

- 18.The yield was determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture using 1 mg/mL methenamine as an internal standard.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.