Abstract

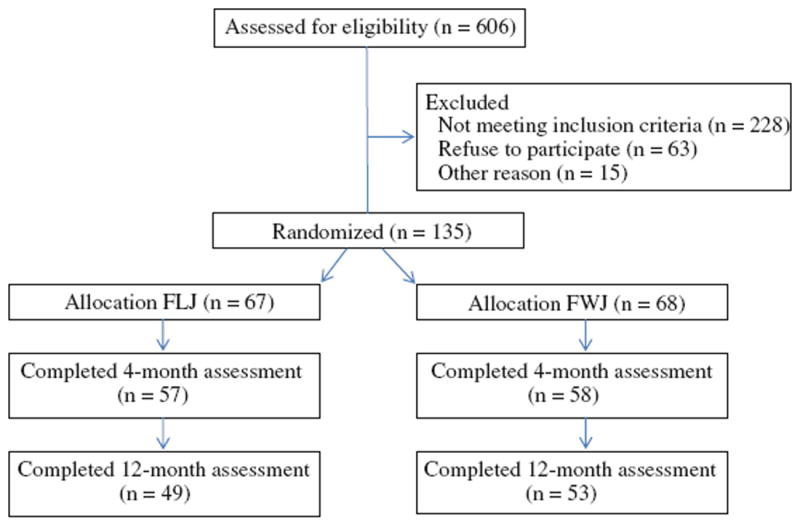

American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) populations are disproportionately at risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, and obesity, compared with the general US population. This article describes the həli?dxw/Healthy Hearts Across Generations project, an AIAN-run, tribally based randomized controlled trial (January 2010–June 2012) designed to evaluate a culturally appropriate CVD risk prevention program for AI parents residing in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. At-risk AIAN adults (n = 135) were randomly assigned to either a CVD prevention intervention arm or a comparison arm focusing on increasing family cohesiveness, communication, and connectedness. Both year-long conditions included 1 month of motivational interviewing counseling followed by personal coach contacts and family life-skills classes. Blood chemistry, blood pressure, body mass index, food intake, and physical activity were measured at baseline and at 4- and 12-month follow-up times.

Keywords: American Indians, Alaska Natives, Cardiovascular, Heart disease, Intervention, Motivational interviewing

Introduction

Increased physical activity and healthful eating have been shown to reduce weight and the risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD; Ignarro et al., 2007). However, American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) populations experience significant disparities in CVD, diabetes, and obesity that cannot be accounted for solely by level of physical activity and food choices (Lee et al., 1990). In AIAN populations, under-explored factors, such as historical trauma, substance use, and mental health, form a complex web of risk factors (Walters et al., 2002) that may be related to the development and onset of CVD. Moreover, the effectiveness of any CVD intervention depends on adherence to CVD risk-reduction regimens, such as regular exercise and healthful eating, which is difficult in AI communities with limited environmental resources (e.g., topography conducive to exercise); economic resources (e.g., money to buy fresh produce vs. fast food); and physical capacity (e.g., mobility for exercise). Clearly, more information is needed on cost-effective and culturally relevant methods for AIAN people to obtain maximal results from CVD risk-reduction interventions.

In this article, we describe an AIAN-run and tribally based randomized controlled trial developed to evaluate a culturally appropriate, feasible, and scalable CVD risk prevention program for AIAN parents at risk for CVD residing in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Utilizing a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach, the tribal community named the project “həli?dxw,” a Coast Salish word meaning “helping someone live, giving someone life.” This project was a multidisciplinary collaboration among experienced tribal care providers at the Tribal Health Clinic, AIAN and non–AIAN researchers at the University of Washington (UW), tribal community leaders in the Northern Puget Sound, national consultants with content expertise, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The həli?dxw project aimed (1) to assess feasibility and initial efficacy of a culturally adapted intervention targeting diet and exercise compared to a family life-skills building intervention and (2) to strengthen the tribal research infrastructure. The comparison condition was chosen because it provided a curriculum that was already under development in the tribal community and was culturally appropriate for the targeted region; it included knowledge and skills that the tribe deemed useful; and it could function as a time-and-attention control, but did not include any topics related to diet or exercise. Additionally, we were interested in decreasing CVD risk in adults as well as in exploring whether positive changes in adult caregivers also resulted in improvements in their children’s diet and exercise. There is evidence that environmental approaches to behavior change (e.g., improving children’s food choices at home) may be more effective than parent education or the institution of rewards and punishments (Epstein, 1995; McLean et al., 2003; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2003). The Indigenist stress-coping model (Walters & Simoni, 2002; Walters et al., 2002), social learning theory (Scott & Dadds, 2009), motivational interviewing (MI) theory (Rollnick et al., 2007), and prior work on culturally appropriate interventions to promote AIAN health (LaMarr & Marlatt, 2007) informed the conceptual basis of the two conditions. In this article, we describe the intervention strategies that were developed and the randomized controlled trial design.

All parties were committed to a CBPR approach (Mohammed et al., 2012; Walters et al., 2009), which included respect for the tribes’ autonomy, sovereignty, and confidentiality, as well as subsequent dissemination of the findings to further the implementation of culturally relevant and cost-effective programs. Solidifying the partnership, the UW research team received approval from the tribal council with a tribal resolution in support of the study.

Early in the planning stages, the UW and Northwest Tribe research teams met with Tribal Health Clinic personnel and tribal elders and attended several elder and community events to identify relevant content, design, process, and cultural concerns and challenges. Themes that emerged included the importance of developing a non-stigmatizing intervention with a focus on parents to promote intergenerational wellness. Additionally, the community indicated they preferred the use of a comparison condition rather than a control group or wait-list control group design. We carefully considered and eventually rejected other intervention designs after community consultation. For example, we considered a wait-list control condition design so that no respondent would be denied participation in the main intervention; however, we felt that a within-subject design would suffer from contamination and would neither optimize the tribal community’s readiness for change related to wellness issues nor respect the tribe’s decision to eschew a wait-list control condition. Additionally, when conducting a study in a reservation environment or an environment with established hardships such as poverty, parsimony of research activities is prudent in terms of financial, social, and cultural costs as well as minimizing intrusion and burden on research participants. Given these concerns, the use of the comparison versus control condition provided an ideal scientific context for conducting two simultaneous trials (each serving as a control for the other) within one study. Enrollment, randomization, and follow-up efforts were not duplicated, yet sufficient power was maintained to test each of the interventions in isolation, as well as to test for any synergistic/antagonistic relationships between the interventions of interest. This approach could easily be replicated with other similarly potentially parallel interventions in resource-challenged settings.

A tribal Federal-wide Assurance of Protection for Human Subjects was established to secure a tribally designated institutional review board. Additionally, based on previous work by the UW team (Walters & Simoni, 2009) and the Indigenous Research Protection Act (http://www.ipcb.org/publications/policy/files/irpa.html), a Research Protocol Code was drafted with guiding principles and expected cultural protocols that have at their core the honoring of tribal sovereignty and guarantee of cultural safety. Finally, we created a data-sharing agreement that included protocols for academic partner data stewardship and mutual data responsibilities, as well as protocols for all dissemination and publication activities. Throughout the developmental phases of the project, the academic and community researchers worked closely with the Community Advisory Board to review materials for the study and, as in the case of the data-sharing agreement, the Executive Director for Health and Human Services and the tribal attorney.

Research Methods

Eligibility Criteria

Potential participants were included in the study if they (1) were 18 years of age or older, (2) were a tribal member or a parent/guardian of a tribal member who was a minor and living in the guardian’s home more than half the time, (3) had a child they cared for at least half the time (referred to as the target child), (4) had a residence on or within 20 miles of the tribal reservation boundary, (5) had a body mass index (BMI) between 25 and 50, and (6) passed the physical health examination administered by study nursing staff or received physician approval to participate in the study if they were potentially at risk (i.e., reported a history of pre-diabetes, diabetes, or chest pain; had a systolic blood pressure ≥150 mmHG, a diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHG, a glucose level ≥200 mg/dL, a hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] level ≥9.0 mmol/L, or a total cholesterol level ≥300 mg/dL). In the case of multiple potential target children, the child closest to the age of 5 years was selected to ensure their developmental ability to participate in group and family-based intervention activities.

Participants were excluded from the study if they (1) had extreme hypertension, severe heart failure, or severe valvular heart disease, (2) were currently enrolled in an organized weight-loss program or taking over-the-counter or prescription weight-loss medications, (3) had undergone or planned to undergo obesity surgery, or (4) were pregnant.

Data collection occurred from January 2010 to February 2012.

Recruitment

Tribal and community members were informed of the study via tribal newsletters; tribal cable TV; announcements posted at the Tribal Health Clinic and other tribal agencies; as well as program-staffed booths at health fairs, community gatherings, and tribal meetings. Advertisements were placed in local newspapers within the 20-mile reservation boundary. Additionally, health care providers at the Tribal Health Clinic wore a button that read “Ask me about the Healthy Hearts Study.” Participants were also recruited from an earlier survey phase of the study.

Enrollment and Randomization

Interested participants contacted study staff, and pre-screen interviews were conducted over the phone or in person. A baseline assessment was scheduled for eligible participants. At the baseline assessment, participants were consented and enrolled, provided a fasting blood sample, and engaged in a 1-h computer-assisted behavioral assessment. After the baseline assessment, participants were introduced to an MI counselor, and an appointment for their first MI session was arranged. At the first MI session, participants were randomly assigned to one of the two trial arms using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes containing the intervention assignment, which the study staff member opened at the moment of randomization. To reduce opportunities for selection bias and confounding (Bland, 2000), participants were allocated randomly within blocks of four. Additionally, for each adult recruited to participate in the study, we sought to enroll the target child to track their height and weight measurements as well (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Project həli?dxw recruitment

Intervention Arms

Participants in each of the two arms engaged in a series of activities over a 12-month period. These included, first, 4–5 weekly sessions with an MI counselor to increase commitment to program outcomes and to identify personal goals. Then, personal coaches met with participants in person or talked with them over the phone three times per month for the duration of the intervention to bolster MI skills, revise personal goals as necessary, and conduct monthly check-ins. They provided key social support tailored to the needs of the individual participant (e.g., going for walks with the participant, making home visits). Finally, monthly skills-building group sessions were held for all participants who completed the MI sessions. These group sessions lasted 2–3 h and were held during weekday evenings. Manuals and training materials were developed for all activities, and specialized training for all interventionists was provided.

Both conditions involved comparable time commitments, activities, and culturally infused practices; only the intervention content in each varied. In the treatment arm, the focus was on cardiovascular health with a focus on reduction of BMI. Specifically, the MI component for the treatment condition targeted (1) increasing physical activity or movement for the parent and family, (2) reducing the consumption of snack foods, sweets, and sugared soft drinks, (3) increasing the availability of fresh fruits and vegetables in the home, and (4) decreasing sedentary activities and screen time. Personal coaches focused on physical health–related support and activities, and the group sessions included cooking and exercise classes.

MI is an approach to support behavioral change in individuals that is consistent with core AIAN values and practices. Specifically, MI is a “way of being” that values the co-development of a respectful relationship and capitalizes on the role of partnership and non-interference. MI has been shown to be effective in a wide range of behavioral health treatments in AIAN populations (Duran et al., 2010; Gilder et al., 2007; Venner et al., 2007). We culturally tailored the MI approach to build on the individual’s own motivations and sense of collective and individual agency in working for their healing, healthy lifestyles, and behavioral practices that could lead to reduced BMI; identified strengths and resiliencies that the person already had within them in activating behavioral change for better eating and activity habits; assisted them in identifying and addressing barriers to change; and visited and honored their path and choices at that time and place.

The comparison arm was based on a previously developed tribal intervention called the Family Life Journey, which focuses on increasing family cohesiveness, communication, and connectedness. The Family Life Journey curriculum was adapted from of one of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s “Best Practices”—the Canoe Journey Life’s Journey: A Life Skills Manual for Native Adolescents (LaMarr & Marlatt, 2007), a program that the tribal Principal Investigator had initiated at the tribal community. The corresponding MI goals were (1) identifying cultural and familial values, (2) identifying rituals and routines for families, (3) cultivating family connectedness and communication skills, (4) developing strengths among individual family members, and (5) increasing play and fun time within families. Personal coaches worked with families on related activities such as creating family scrapbooks or photo journals. The group sessions included family kite making, drum making, and basket weaving classes. Both interventions utilized a multilevel approach in which individually tailored components in the MI were followed by a built-in social support component via the personal coaches, interspersed with group classes to reinforce skills-building in the context of other community members.

Incorporation of Cultural Components

The interventions were designed to incorporate cultural components and to emphasize a holistic approach to health consistent with Coast Salish values. Specifically, the proposed intervention for both conditions contained the following four interrelated domains of mind, body, spirit, and emotion. Moreover, several metaphors grounded in local culture were used, including one based on the canoe journey, a highly significant event for Coast Salish peoples. Just as thoughtful planning, diligent preparation, and careful implementation ensure a safe and successful canoe journey, so, too, was participation in the intervention activities presented as capable of leading to desired outcomes for families and communities. Additionally, the life cycle of the salmon was used as a powerful metaphor for the parents. Just as salmon endure hardship, swimming upstream to go to their original breeding grounds to deliver the next generation, parents are encouraged to prioritize the health of future generations by reflecting upon the overwhelming obstacles their ancestors overcame and by accepting the significant challenges required of them now to ensure the survival of future generations. Finally, the orca or blackfish (i.e., killer whale) was used metaphorically for successful family relations. Orca offspring remain with their mothers their entire lives, creating a lifetime bond, which allows Orca family groups to develop distinct vocal dialects, preserve family traditions, and create lasting connections (LaMarr & Marlatt, 2007). Intervention families were prompted to think about the importance of their own family, preserving traditions, increasing communication, transmitting cultural information across generations, as well as the importance of play.

Interventionist

We hired three part-time staff members to deliver the MI counseling and two part-time staff members to function as personal coaches. Four were AIAN and were between 18 and 35 years of age. All staff members were interviewed by community and academic team members and were trained to deliver the two interventions of the study. To control for exposure and proficiency biases, all MI counselors and personal coaches implemented interventions for both conditions. Follow-up assessments were conducted by study staff who were not MI counselors in either condition. All study staff attended 2 weeks of training on intervention protocols and MI. In addition, personal coaches attended a 1-day training on types of CVD–related family activities to engage in with their participant, and MI counselors attended weekly supervision meetings for the first 3 months that tapered off to twice-monthly supervision meetings.

Fidelity of the Intervention

Detailed curriculum manuals, careful selection of study personnel, thorough specialized training, and ongoing supervision and monitoring of staff members were all used to enhance treatment fidelity and quality assurance in the implementation of the intervention. Specifically, MI therapists completed curriculum log sheets indicating the extent to which they covered scheduled topics for each MI session and a session-evaluation questionnaire at the end of each MI session to rate their adherence to the curriculum, ability to engage participants, and ability to control the process while maintaining mutual respect for participants. Additionally, they completed measures of participants’ reactions to the interventions, i.e., how much they appeared to enjoy, learn from, and actively participate in the interventions. During supervision, the MI counselors used structured MI treatment fidelity instruments. The tribe preferred that sessions not be recorded.

Assessment Schedule and Measures

Assessments were planned for all participants at baseline and two follow-up times (at 4 and 12 months). Participants were given a $20 food card for each MI session attended, $40 for the baseline assessment, $45 for the 4-month follow-up assessment, and $50 for the 12-month assessment. Additionally, for each group session attended, participants received a raffle ticket for a chance to win one of three gifts valued at $300.

Sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., gender, age, education, income, relationship status, employment status, disability, and number of household members) were collected and data on trauma and the cultural protective factors identified in the Indigenist stress-coping model (Walters et al., 2002) were assessed in order to examine potential moderators and/or mediators of the intervention’s effectiveness. The assessment schedule, specific scales, and relevant references for the major variables of interest are presented in the Table 1. The primary outcome (BMI) and main secondary outcomes (physical and sedentary activity levels, food intake) are described in more detail below.

Table 1.

Measures and assessment schedule

| Measures | Assessment points

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (BL) | T2 (M4) | T3 (M12) | |

| Family wellness measures | |||

| Primary outcome | |||

| Body mass index | A/C | A/C | A/C |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Physical and sedentary activity | |||

| Physical activity questionnaire (Paffenbarger et al., 1983) | A | A | A |

| Child and parent activity levels (Davison et al., 2003) | A | A | A |

| Television viewing (Dennison et al., 2004) | A | A | A |

| Food activity | |||

| Home health survey (Bryant et al., 2008) | A | A | A |

| Food adherence (Adapted) (Campbell et al., 2007) | A | A | A |

| Child Feeding Questionnaire (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1998; Birch et al., 2001) | A | A | A |

| Family meals (McGarvey et al., 2004) | A | A | A |

| Biological measures | |||

| Serum total cholesterol | A | A | A |

| Triglycerides | A | A | A |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol | A | A | A |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol | A | A | A |

| Fasting glucose | A | A | A |

| Dyslipidemia | A | A | A |

| Low-level inflammation | A | A | A |

| Hemoglobin A1c | A | A | A |

| Blood pressure and hypertension | A | A | A |

| Family life journey measures | |||

| Primary outcome | |||

| Parenting Sense of Competence Scale (Gibaud-Wallston & Wandersman, 1978) | A | A | A |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Parental Discipline Scale(Loeber et al., 1998) | A | A | A |

| Parent Praise (Thornberry et al., 1995) | A | A | A |

| Parent Practices Scale (Strayhorn & Weidman, 1988) | A | A | A |

| Stressors | |||

| Microaggressions Distress Scale (Walters, 2005) | A | A | |

| The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (Foa et al., 1997) | A | A | |

| Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale (Radloff, 1977) | A | A | |

| Self-perceived weight (Strauss, 1999) | A | A | |

| MOS short form-12 (SF12) health status (Hurst et al., 1998; Ware et al., 1996) | A | A | |

| Health conditions (California Health Interview Survey, 2007) | A | A | |

| Household food security (Nord et al., 2007) | A | A | |

| Protective factors | |||

| Spiritual beliefs inventory (Holland et al., 1998) | A | A | |

| Urban American Indian identity scale actualization subscale (Walters, 1999) | A | ||

| Sense of Community Index (SCI) (Chavis et al., 1986; Chipuer and Pretty, 1999) | A | A | |

| The Communal Mastery Scale (Hobfoll et al., 2002) | A | A | |

| The MOS Social Support Survey (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991) | A | A | |

A Adult, C Child, BL Baseline, M Month, T Time

BMI and Waist-to-Hip Ratio

For both children and adults, weight and height were measured with a portable digital weight scale, a height-measuring device, and a handheld body fat monitor (Omron HBF-306C Body Fat Analyzer; Omron Healthcare, Kyoto, Japan). Weight was measured directly to the nearest 0.1 kg on a calibrated digital scale in light clothing and without shoes. Height was measured to the nearest centimeter using a wall-mounted ruler. BMI was computed as weight(kg)/(height[m])2. Measurement of waist-to-hip ratio was done using a measuring tape around the waist and hips.

Three-Day Food and Physical Assessment

At each assessment, parents were instructed to record type of food and serving size for everything they consume over the next 3-day period. Additionally, parents were instructed to record their level of physical activity over the same 3 days using a G-Sensor 2026 Accelerometer pedometer. Parents were instructed on the proper use of the pedometer for all waking activities, with the exception of bathing. The parent was given a log sheet and asked to record times the pedometer was not worn. After the 3-day period, a staff member phoned the parents to record their food intake and physical activity levels.

Food Intake

Food intake was assessed for the whole family and for the target child only. As shown in the Table 1, several validated scales were used to capture (1) aspects of parents’ child-feeding perceptions, attitudes, and practices, as well as relationships to children’s developing food acceptance patterns, the controls of food intake, and obesity (Birch et al., 2001), (2) characteristics of the home environment that might influence healthy weight behaviors in children including diet and physical activity (Bryant et al., 2008), and (3) parental report of mealtime behaviors such as frequency of planning and eating meals together (McGarvey et al., 2004).

Physical and Sedentary Activity

Parents were asked to complete a self-reported measure of their behavior in support of their child’s activity levels (Davison et al., 2003). Additionally, parents’ report the number of hours of screen time for their child (i.e., time spent watching TV, watching videos, playing computer games, and surfing the Internet), and whether the child had a TV in his or her room or watched TV while eating (Dennison et al., 2004).

Blood Chemistry Measures

Participants were instructed to fast for at least 12 h prior to their clinical health examination administered at baseline. Blood samples were collected at baseline and each follow-up to test for serum total cholesterol (mg/dL); triglycerides; high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C); fasting glucose (determined by enzymatic methods using a Hitachi 737 Chemistry Analyzer and reagents [Boehringer Mannheim Diagnostics, Inc., Indianapolis, IN]), with a diagnosis of diabetes if fasting glucose level >7 mmol/L (>126 mg/dL); low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C; determined using the Friedewald formula, but not calculated if triglycerides level was >4.52 mmol/L [>400 mg/dL]); dyslipidemia (total cholesterol >6.21 mmol/L [>240 mg/dL], LDL-C >4.14 mmol/L [>160 mg/dL]), HDL-C < 0.91 mmol/L [<35 mg/dL], and high triglycerides level >2.82 mmol/L [>250 mg/dL]); low-level inflammation via high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP >3.0 mg/L); and glycosylated hemoglobin level (HbA1c), with a diagnosis of diabetes if the HbA1c level is at or equal to 6.5 %. No blood was retained from the fasting blood draw.

Blood Pressure and Hypertension

Blood pressure was measured with a mercury sphygmomanometer three times after a 5-min rest. The average of the second and third readings was used to estimate systolic (first Korotkoff sound) and diastolic (fifth Korotkoff sound) blood pressure. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure >140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >90 mmHg.

Quality and Process Assessments

Careful records were kept of participant flow and reasons for refusal. Data collected on intervention process included extent of participation, amount of time dedicated to each activity, satisfaction, and barriers. Additionally, we sought feedback from participants and staff on ways to improve the intervention activities and to increase level of involvement.

Results Dissemination

The last phase of the project will involve results dissemination to the tribal council, the tribal community, and AIAN health care providers. Following a CBPR approach (Roe et al., 1995; Walters & Simoni, 2009), we will hold at least two community town meetings on the reservation to share with the community the findings from all phases of the research project and to elicit feedback on (1) data interpretation, (2) potential risks and benefits to the community, (3) dissemination strategies, (4) community and economic readiness to implement the intervention, (5) implementation strategies, and (6) transferability to other tribal nations. We will synthesize community feedback into a final report for submission to the tribal council for approval. Additionally, we will discuss planned publications and conferences for presentation of the material with the tribal council. After receiving approval from the tribal council, we will prepare the final report for community consumption and proceed with publishing the results in scientific journals, AIAN newsletters, and other outlets identified by the community. We recognize the overarching principle of tribal involvement in these processes and the importance of honoring our data-sharing agreement.

Challenges and Strengths

Challenges of the həli?dxw project included (1) retaining parents for a year-long intervention with additional follow-up, (2) monitoring fidelity without video or audio analyses of the MI meetings, (3) implementing two interventions at the same time, (4) minimizing diffusion of intervention effects across arms, and (5) managing immense social and family pressures (e.g., multiple losses and funerals).

A major strength of the study was the high level of engagement by the parents in the individualized MI component of the intervention. Interestingly, parents were less interested in attending the group meetings, which they stated taxed their time and energy. One community member noted that group meetings were difficult, in part, because they served as reminders of stressful community events (e.g., funerals, memorials). Finally, a number of community members were interested in participating, but they did not meet our eligibility criteria (e.g., their BMI was outside of our range). This was disheartening to many of the AIAN staff who wanted to support those likely at greatest risk in their communities.

A major strength, as well as challenge of the study, was the communities’ encouraging us to go off-site from the Tribal Health Clinic and implement the project at a free-standing building. This provided “cultural safety” for community members and reduced participant fears about gossip at the Tribal Health Clinic. However, this approach made it more difficult to coordinate health services when participants needed immediate health care upon screening or needed follow-up appointments with a physician or health care provider. Finally, we were not able to develop environmental interventions that the community desired (e.g., community gardens, footpaths). As a result, environmental interventions are currently being discussed with the community for future planning efforts. Moreover, our results will likely indicate which environmental interventions will be most effective and relevant for families.

Innovation

This study fills a gap in the CVD prevention literature, as it provides empirical data on a culturally relevant and comprehensive CVD risk-reduction intervention for AIAN adults. It makes several distinctive contributions including (1) using an Indigenist stress-coping model and empirical measures that capture specific, culturally based factors (e.g., historical trauma), (2) focusing on parents, (3) focusing on CVD prevention issues among Northwestern AIAN communities, (4) incorporating some of the same measures (biological and behavioral) used in the Strong Heart Study (Howard et al., 1999) and the Inter-Tribal Heart Project (Archer et al., 2004), which allows our data to be compared with those from these studies, (5) incorporating an MI approach to improving heart health, and (6) incorporating an interdisciplinary and intertribal team approach with AIAN community members, leaders, and elders. If successful, this study will provide useful scientific and practical information in several areas, including the feasibility of delivering such interventions in a real-world practice setting, the appeal of such a program to parents and health care providers, the cost of such a program, and the benefits in terms of health care utilization. The confluence of the research-supportive practice environment and this team of investigators provided a rare opportunity to obtain this information.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a cooperative agreement between the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the Indigenous Wellness Research Institute, University of Washington School of Social Work, and a subcontract with the Northwest Tribal partner (U01-HL 087322). Additional support was provided by an NHLBI Diversity Supplement Grant. We want to acknowledge Drs. Robert Jefferies and Bonnie Duran for their consultation, feedback, and support. We are particularly grateful to the Northwest Tribal government and leaders for supporting this work. Specifically, we acknowledge the following individuals: Melvin R. Sheldon, Jr., Chairman; Marlin Fryberg, Jr., Vice Chairman; Chuck James, Treasurer; Marie Zachuse, Secretary; Glen Gobin, Board member; Don Hatch, Jr., Board member; and Mark Hatch, Board member. Additionally, we thank the following tribal and allied AI community leaders and professionals for their support and guidance: Sheryl Fryberg, Shelly Lacy, Paula Cortez, Alan Harney, Karen Fryberg, Dr. Lise Alexander, and Dr. John Okema. We are also grateful for the support and advice from the following key staff and community members who assisted the study team and provided advice and guidance on ways to implement the study in the community: Della Hill, Virginia Carpenter, Clarissa Johnny, Hank Gobin, Sandy Tracy, Sherry Guzman, Marsha Gray-Airis, Tammy Dehnhoff, Verna Hill, Natalia Knapp, Frieda Williams, Marina Benally, Kathy Hurd, Jason Gobin, Dawn Young, Alison Bowen, and Veronica Leahy. Finally, we are humbled by the strength and resiliency of the families we have had the privilege to work with in this study. We deeply appreciate their willingness to support such an effort and to share their stories and experiences in order to develop an intervention to better the heart health for their community and future generations.

Contributor Information

Karina L. Walters, Indigenous Wellness Research Institute, School of Social Work, University of Washington, 4101 15th Ave NE, Seattle, WA 98105, USA, kw5@uw.edu

June LaMarr, Tulalip Tribes, Tulalip, WA, USA.

Rona L. Levy, School of Social Work, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Cynthia Pearson, Indigenous Wellness Research Institute, School of Social Work, University of Washington, 4101 15th Ave NE, Seattle, WA 98105, USA.

Teresa Maresca, Department of Family Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Selina A. Mohammed, Bothell Nursing Program, University of Washington, Bothell, WA, USA

Jane M. Simoni, Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Teresa Evans-Campbell, Indigenous Wellness Research Institute, School of Social Work, University of Washington, 4101 15th Ave NE, Seattle, WA 98105, USA.

Karen Fredriksen-Goldsen, School of Social Work, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Sheryl Fryberg, Tulalip Tribes, Tulalip, WA, USA.

Jared B. Jobe, Division of Cardiovascular Sciences, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA

References

- Archer SL, Greenlund KJ, Valdez R, Casper ML, Rith-Najarian S, Croft JB. Differences in food habits and cardiovascular disease risk among Native Americans with and without diabetes: The Inter-Tribal Heart Project. Public Health Nutrition. 2004;7:1025–1032. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Nutrient Intakes and physical measurements. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 1998. Report No. 4805.0. [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Fisher JO, Grimm-Thomas K, Markey CN, Sawyer R, Johnson SL. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: A measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite. 2001;36:201–210. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland M. An introduction to medical statistics. 3. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant MJ, Ward DS, Hales D, Vaughn A, Tabak RG, Stevens J. Reliability and validity of the Healthy Home Survey: A tool to measure factors within homes hypothesized to relate to overweight in children. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2008;5:23. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2005 Adult Questionnaire, version 6.3. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KJ, Crawford DA, Salmon J, Carver A, Garnett SP, Baur LA. Associations between the home food environment and obesity-promoting eating behaviors in adolescence. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2007;15:719–730. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavis DM, Hogge JH, McMillan DW, Wandersman A. Sense of community through Brunswick’s lens: A first look. Journal of Community Psychology. 1986;14:24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chipuer HM, Pretty GMH. A review of the sense of community index: Current uses, factor structure, reliability and further development. Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:643–658. [Google Scholar]

- Davison KK, Cutting TM, Birch LL. Parents’ activity-related parenting practices predict girls’ physical activity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2003;35:1589–1595. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000084524.19408.0C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison BA, Russo TJ, Burdick PA, Jenkins PL. An intervention to reduce television viewing by preschool children. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:170–176. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran B, Harrison M, Shurley M, Foley K, Morris P, Davidson-Stroh L, et al. Tribally-driven HIV/AIDS health services partnerships: Evidence-based meets culture-centered interventions. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services. 2010;9:110–129. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein L. Exercise in the treatment of childhood obesity. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 1995;19(Suppl):S117–S121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Gibaud-Wallston J, Wandersman LP. Development and utility of the Parenting Sense of Competence Scale; Paper presented at the 86th annual meeting of the American Psychological Association; Toronto, Canada. 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Gilder DA, Luna JA, Calac D, Moore RS, Monti PM, Ehlers CL. Acceptability of the use of motivational interviewing to reduce underage drinking in a Native American community. Substance Use and Misuse. 2007;46:836–842. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.541963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Jackson A, Hobfoll I, Pierce CA, Young S. The impact of communal-mastery versus self-mastery on emotional outcomes during stressful conditions: A prospective study of Native American women. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:853–871. doi: 10.1023/A:1020209220214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JC, Kash KM, Passik S, Gronert MK, Sison A, Lederberg M, et al. A brief spiritual beliefs inventory for use in quality of life research in life-threatening illness. Psycho-oncology. 1998;7:460–469. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199811/12)7:6<460::AID-PON328>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard BV, Lee ET, Cowan LD, Devereux RB, Galloway JM, Go OT, et al. Rising tide of cardiovascular disease in American Indians. The Strong Heart Study Circulation. 1999;99:2389–2395. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.18.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst NP, Ruta DA, Kind P. Comparison of the MOS short form-12 (SF12) health status questionnaire with the SF36 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. British Journal of Rheumatology. 1998;37:862–869. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.8.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignarro LJ, Balestrieri ML, Napoli C. Nutrition, physical activity, and cardiovascular disease: An update. Cardiovascular Research. 2007;73:326–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMarr J, Marlatt GA. Canoe journey life’s journey: A life skills manual for native adolescents. Center City, MN: Hazelden Publishing and Educational Services; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lee ET, Welty TK, Fabsitz R, Cowan LD, Le NA, Oopik AJ, et al. The Strong Heart Study. A study of cardiovascular disease in American Indians: Design and methods. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1990;132:1141–1155. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB. Antisocial behavior and mental health problems: Explanatory factors in childhood and adolescence. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey E, Keller A, Forrester M, Williams E, Seward D, Suttle DE. Feasibility and benefits of a parent-focused preschool child obesity intervention. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1490–1495. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean N, Griffin S, Toney K, Hardeman W. Family involvement in weight control, weight maintenance and weight-loss interventions: A systematic review of randomised trials. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2003;27(9):987–1005. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed SA, Walters KL, LaMarr J, Evans-Campbell T, Fryberg S. Finding middle ground: Negotiating University and tribal community interests in community-based participatory research. Nursing Inquiry. 2012;19:116–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2011.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Perry C, Story M. Correlates of fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents. Findings from Project EAT. Preventive Medicine. 2003;37(3):198–208. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord M, Andrews M, Carlson S. Measuring food security in the United States: Household food security in the United States, 2006. Economic Research Service, U.S Department of Agriculture; 2007. Economic Research Report No (ERR-49) [Google Scholar]

- Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Wing AL, Hyde RT, Jung DL. Physical activity and incidence of hypertension in college alumni. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1983;117:245–257. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roe KM, Minkler M, Saunders FF. Combining research, advocacy, and education: The methods of the Grandparent Caregiver Study. Health Education Quarterly. 1995;22:458–475. doi: 10.1177/109019819502200404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational interviewing in health care: Helping patients change behavior. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Scott S, Dadds MR. Practitioner review: When parenting training doesn’t work: Theory–driven clinical strategies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2009;50:1441–1450. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss RS. Self-reported weight status and dieting in a cross-sectional sample of young adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153:741–747. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.7.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strayhorn JM, Weidman CS. A Parent Practices Scale and its relation to parent and child mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1988;27:613–618. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198809000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Huizinga D, Loeber R. The prevention of serious delinquency and violence: Implications from the program of research on the causes and correlates of delinquency. In: Howell JC, Krisberg B, Hawkins DJ, Wilson JJ, editors. Serious, violent, and chronic juvenile offenders: A sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1995. pp. 213–237. [Google Scholar]

- Venner KL, Feldstein SW, Tafoya N. Helping clients feel welcome: Principles of adapting treatment cross-culturally. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2007;25:11–30. doi: 10.1300/J020v25n04_02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL. Urban American Indian identity attitudes and acculturation styles. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 1999;2:163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL. Historical trauma, microaggressions, and colonial trauma response: Indigenous concepts in search of a measure; Paper presented at the 2nd international Indigenous health knowledge development conference; Vancouver, Canada. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Simoni JM. Reconceptualizing native women’s health: An “indigenist” stress-coping model. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:520–524. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Simoni JM. Decolonizing strategies for mentoring American Indians and Alaska Natives in HIV and mental health research. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 1):S71–S76. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.136127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Simoni JM, Evans-Campbell T. Substance use among American Indians and Alaska natives: Incorporating culture in an “indigenist” stress-coping paradigm. Public Health Reports. 2002;117(Suppl 1):S104–S117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Stately A, Evans-Campbell T, Simoni JM, Duran B, Schultz K, et al. “Indigenist” collaborative research efforts in Native American communities. In: Stiffman AR, editor. The field research survival guide. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 146–173. [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]