Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE:

Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) due to pulmonary surfactant deficiency is heritable, but common variants do not fully explain disease heritability.

METHODS:

Using next-generation, pooled sequencing of race-stratified DNA samples from infants ≥34 weeks’ gestation with and without RDS (n = 513) and from a Missouri population-based cohort (n = 1066), we scanned all exons of 5 surfactant-associated genes and used in silico algorithms to identify functional mutations. We validated each mutation with an independent genotyping platform and compared race-stratified, collapsed frequencies of rare mutations by gene to investigate disease associations and estimate attributable risk.

RESULTS:

Single ABCA3 mutations were overrepresented among European-descent RDS infants (14.3% of RDS vs 3.7% of non-RDS; P = .002) but were not statistically overrepresented among African-descent RDS infants (4.5% of RDS vs 1.5% of non-RDS; P = .23). In the Missouri population-based cohort, 3.6% of European-descent and 1.5% of African-descent infants carried a single ABCA3 mutation. We found no mutations among the RDS infants and no evidence of contribution to population-based disease burden for SFTPC, CHPT1, LPCAT1, or PCYT1B.

CONCLUSIONS:

In contrast to lethal neonatal RDS resulting from homozygous or compound heterozygous ABCA3 mutations, single ABCA3 mutations are overrepresented among European-descent infants ≥34 weeks’ gestation with RDS and account for ∼10.9% of the attributable risk among term and late preterm infants. Although ABCA3 mutations are individually rare, they are collectively common among European- and African-descent individuals in the general population.

KEY WORDS: genetic association studies, neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, newborn, respiratory distress syndrome

What’s Known on This Subject:

Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome is the most common respiratory cause of mortality and morbidity among US infants aged <1 year. Although neonatal respiratory distress syndrome is a heritable disorder, common genetic variants do not fully explain disease heritability.

What This Study Adds:

Single ABCA3 mutations are overrepresented among term and late preterm (≥34 weeks’ gestation) European-descent infants with RDS. Although ABCA3 mutations are individually rare, they are collectively common in the European- and African-descent general population, present in ∼4% of individuals.

Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) is the most common respiratory cause of mortality and morbidity among infants aged <1 year in the United States.1 RDS is usually attributed to a developmentally regulated deficiency of pulmonary surfactant, a phospholipid-protein complex that is synthesized, packaged, and secreted by alveolar type 2 cells that lowers surface tension and maintains alveolar expansion at end expiration. However, disease heritability demonstrated in twin studies (∼0.29–0.67),2,3 the persistence of gender and racial disparities in disease risk despite widespread use of surfactant replacement therapy,1 and lethal mutations in surfactant-associated genes4–6 suggest that genetic mechanisms also contribute to the risk for neonatal RDS.

Previous studies investigating the genetic contribution to the risk for neonatal RDS demonstrated modest statistical associations with common variants in surfactant-associated candidate genes.7,8 However, these studies were limited by small sample sizes, phenotypic heterogeneity, and genotyping of common variants that are more likely to have smaller effect sizes.9 Studies in other complex diseases suggest that rare, deleterious, highly penetrant variants at multiple gene loci may account for disease heritability.9,10 Disruption of fetal–neonatal pulmonary transition by RDS exerts strong purifying selection pressure to reduce frequencies of deleterious variants that cause RDS (minor allele frequency <0.05). For example, surfactant protein B is required for pulmonary surfactant function, and deleterious variants in the surfactant protein B gene (SFTPB) are extremely rare (<0.1% of the Missouri population) and not associated with increased risk for RDS in case-control studies.11,12 Homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in SFTPB and the ATP-binding cassette transporter-A3 gene (ABCA3) result in lethal neonatal RDS, whereas mutations in the surfactant protein C gene act in a dominant manner.4–6

High-resolution, high-throughput, low-cost, next-generation sequencing strategies, computational algorithms for rare variant discovery, in silico algorithms that predict functionality, and statistical strategies for collapsing frequencies of deleterious variants have permitted discovery of gene loci with excess, rare mutations associated with complex phenotypes in feasibly sized cohorts.10 Based on previously recognized associations with severe neonatal RDS and/or their critical roles in pulmonary surfactant metabolism, 5 genes were selected: surfactant protein C (SFTPC, NM_003018.3, Gene ID 6440), ABCA3 (NM_001089.2, Gene ID 21), cholinephosphotransferase (CHPT1, NM_020244.2, Gene ID 56994), lysophospholipid acyltransferase (LPCAT1, NM_024830.3, Gene ID 79888), and choline-phosphate cytidylyltransferase (PCYT1B, NM_004845.4, Gene ID 9468). We performed complete exonic resequencing and independent validation to test the hypothesis that excess, rare mutations in these 5 genes increase the risk for neonatal RDS.

Methods

Patient Selection

Disease-Based Cohorts: Infants With and Without RDS

To reduce the contribution of developmental immaturity and enrich for genetic causes of surfactant deficiency, consecutive newborn infants ≥34 weeks’ gestation13 of European and African descent (maternally designated) with and without RDS were recruited from the nurseries at Washington University Medical Center (Table 1).14 A standardized definition of RDS was used: need for supplemental oxygen (fraction of inspired oxygen ≥0.3), chest radiograph consistent with neonatal RDS, and need for continuous positive airway pressure or mechanical ventilation within the first 48 hours of life. Infants without RDS did not have respiratory symptoms but required hospitalization for other neonatal problems (non-RDS). Gestational age was assigned based on best obstetrical estimate. Infants with cardiopulmonary malformations, pulmonary hypoplasia, culture-positive sepsis, chromosomal anomalies, known surfactant mutations, or rapidly resolving RDS (<24 hours after birth) were excluded from study. We randomly excluded 1 of monozygotic twins or twins in whom zygosity could not be reliably determined. Details of the respiratory course and outcome were extracted from clinical chart review.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of European- and African-Descent Disease-Based Groups (N = 513)

| Characteristic | European Descent | P Value | African Descent | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDS (n = 112) | Non-RDS (n = 161) | RDS (n = 44) | Non-RDS (n = 196) | |||

| Gendera | .51 | <.001 | ||||

| Female | 47 (0.42) | 74 (0.46) | 10 (0.23) | 101 (0.52) | ||

| Male | 65 (0.58) | 87 (0.54) | 34 (0.77) | 95 (0.48) | ||

| Gestational age, mean ± SD, wk | 37.0 ± 1.7 | 38.2 ± 1.6 | <.001 | 37.6 ± 2.7 | 38.9 ± 1.7 | .003 |

| Birth weight, mean ± SD, kg | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.7 | .37 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | .08 |

| Route of deliverya | .54 | <.001 | ||||

| Vaginal | 55 (0.49) | 73 (0.45) | 15 (0.34) | 133 (0.68) | ||

| Cesarean | 57 (0.51) | 88 (0.55) | 29 (0.66) | 63 (0.32) | ||

Number of infants (percent).

Disease-Based Cohorts: Referred Infant Samples

We recruited an independent group of infants (≥34 weeks’ gestation) from outside Washington University Medical Center referred for evaluation of severe RDS (eg, prolonged need for ventilatory support and oxygen supplementation) to serve as a replication cohort (Supplemental Table 5). Informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians of all participating infants.

Population-Based Cohort

Anonymized, unselected Guthrie cards were obtained from the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services Newborn Screening Program (year 2000) with a racial composition that reflected the Missouri birth cohort in 2000 (Table 2).11,15,16 The Washington University School of Medicine Human Research Protection Office and the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services approved this study.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Population-Based Cohort (N = 1066)

| Characteristic | African Descent (n = 195) | European Descent (n = 871) |

|---|---|---|

| Females/males | 94/99 | 424/437 |

| EGA, mean ± SD, wk | 38.7 ± 1.8 | 38.9 ± 1.6 |

| Birth weight, mean ± SD, kg | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 0.5 |

Twelve of the 1066 infants did not have demographic information available other than race. EGA, estimated gestational age.

Gene Selection

SFTPC and ABCA3 were selected because rare mutations in both genes cause severe neonatal RDS.4,5 We selected 3 genes encoding key enzymes in the surfactant phosphatidylcholine synthetic pathway: PCYT1B encodes the rate-limiting enzyme in phosphatidylcholine synthesis in fetal lung, CHPT1 encodes the final enzyme of the phosphatidylcholine synthetic pathway, and LPCAT1 encodes the enzyme that rearranges acyl groups to form dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine, the major phospholipid component of pulmonary surfactant. LPCAT1 has also been associated with neonatal RDS in a hypomorphic murine model.17

DNA Isolation and Pool Preparation

Disease-Based Cohort

DNA was isolated from blood by using Puregene DNA isolation kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).14 Equimolar amounts from each individual were combined into 4 race-stratified pools: African-descent RDS (n = 44) or non-RDS (n = 196) and European-descent RDS (n = 112) or non-RDS (n = 161).

Population-Based Cohort

DNA was extracted from Guthrie cards as previously described.11,16 We combined equimolar amounts of DNA from each bloodspot into 5 race-stratified pools of similar size.

Next-Generation Sequencing

Using a next-generation sequencing platform (Illumina, Inc, San Diego, CA), we sequenced all exons and flanking regions (∼50 base pairs) of the 5 genes.15 (Supplemental Table 6) To optimize selection of significance thresholds for detection of rare variants in each sequencing run, we added a 1934 base pair oligonucleotide with no variation and a 335 base pair oligonucleotide containing 15 known insertions, deletions, and substitutions at a frequency of <1 allele per pool (Supplemental Methods).18

The computational algorithm SPLINTER (short indel prediction by large deviation inference and nonlinear true frequency estimation by recursion)18 was used to detect rare variants. We conservatively defined variants as mutations if they resulted in an amino acid change that was predicted by both SIFT (Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant)19 and PolyPhen20 to disrupt protein function or if the variant was previously associated with childhood respiratory disease. Each mutation was confirmed with an independent genotyping strategy (Sequenom, TaqMan, or Sanger resequencing) and linked to its individual sample (Supplemental Tables 7–10).

Statistical Methods

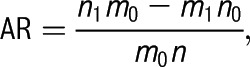

Race-stratified, gene-specific, collapsed frequencies of mutations in RDS and non-RDS infants were compared by using χ2 tests and Fisher’s exact probability tests.10 Because it is unlikely that an individual carries >1 rare mutation at a single gene locus, the number of mutations in a single gene can be collapsed for statistical purposes and compared by using a univariate test.10 Logistic regression was used to determine if rare mutations increase the risk for RDS or have gestational age–specific effects. Fisher’s exact tests and Student’s t tests were used to compare demographic characteristics and disease severity measures between groups. We corrected for multiple comparisons by using the Bonferroni method; the statistical significance level after Bonferroni correction was P ≤ .005 (0.05/10, with 10 being the number of total comparisons for 5 genes and 2 racial groups). Because RDS incidence among infants ≥34 weeks’ gestation is rare (<0.025),13 attributable risk (AR) was calculated by using the formula:

|

where n0 and n1 are the numbers of unexposed and exposed cases, m0 and m1 are the numbers of unexposed and exposed controls, and n = n0+n1.21 SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Next-Generation Sequencing

Inclusion of negative and positive controls for run-specific error models permitted us to achieve high sensitivity (0.99) and specificity (0.99) for detection of rare variants within each pool. We sequenced ∼37 kb per individual with a mean coverage of 82× in the disease-based cohort and 70× in the population-based cohort.

Disease-Based Cohort

European-Descent Infants

Single mutations in ABCA3 were overrepresented among European-descent infants with neonatal RDS: 14.3% of RDS infants carried a single ABCA3 mutation compared with 3.7% of non-RDS infants (P = .002) (Table 3). Two mutations previously associated with respiratory disease in newborns and children, p.R288K (c.863G>A) and p.E292V (c.875A>T),22–24 accounted for 13 of the 16 mutated alleles among RDS infants. Because our sequencing strategy also included exon-flanking regions, we identified 1 RDS infant with an intronic mutation (c.3863-98 C>T) that results in an insertion of 50 amino acids and has been identified in children with lethal RDS.25 No infant had 2 ABCA3 mutations, and no mutations in SFTPC, CHPT1, LPCAT1, or PCYT1B were detected among any European-descent infants in the disease-based cohort.

TABLE 3.

Rare Mutations Identified Among Infants of European Descent

| Gene | Mutation | RDS (n = 112) | Non-RDS (n = 161) | Missouri Population (n = 871) | ESP (n = 3510) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCA3 | R20W | 2 | |||

| R43C | 1 | ||||

| V129M | 1 | ||||

| A132T | 1 | ||||

| V133M | 1 | ||||

| R208W | 1 | ||||

| L212M | 3 | 14 | |||

| P246L | 1 | ||||

| R280C | 1 | ||||

| R280H | 12 | ||||

| R288K | 6 (5.3%)a | 2 (1.2%)a | 14 (1.6%)a | 54 (1.5%)a | |

| E292V | 7 (6.2%)a | 1 (0.6%)a | 1 (0.1%)a | 32 (0.9%)a | |

| V480M | 1 | ||||

| E522K | 1 | ||||

| I561F | 1 | ||||

| G594R | 1 | ||||

| L654V | 2 | ||||

| G668D | 1 | ||||

| R671C | 1 | ||||

| S693L | 1 | 7 | |||

| E725K | 1 | ||||

| T761K | 1 | ||||

| R1081W | 1 | ||||

| I1117M | 1 | ||||

| A1119E | 1 | ||||

| A1297T | 1 | ||||

| I1382M | 1 | ||||

| T1424M | 1 | ||||

| M1428L | 2 | ||||

| R1457Q | 1 | ||||

| A1466T | 1 | ||||

| R1474W | 1 | 3 | 8 | 29 | |

| V1495M | 1 | ||||

| S1516N | 1 | ||||

| R1561Q | 1 | ||||

| V1588M | 1 | ||||

| c.3863-98 C>T | 1 | ||||

| ABCA3 allele (carrier) frequency | 16 (14.3%)a | 6 (3.7%)a | 31 (3.6%)a | 176 (5.0%)a | |

| SFTPC | D15N | 1 | |||

| I26V | 1 | ||||

| A53T | 1 | 1 | |||

| L110R | 1 | ||||

| SFTPC allele (carrier) frequency | 1 (0.1%)a | 4 (0.1%)a | |||

| CHPT1 | S40W | 4 | |||

| W60C | 1 | ||||

| D132E | 2 | ||||

| CHPT1 allele (carrier) frequency | 7 (0.2%)a | ||||

| LPCAT1 | G110S | 1 | |||

| P230S | 1 | ||||

| R237Q | 1 | ||||

| M298V | 1 | ||||

| E312K | 1 | ||||

| F460V | 1 | ||||

| R526W | 1 | ||||

| LPCAT1 allele (carrier) frequency | 1 (0.1%)a | 6 (0.2%)a | |||

| PCYT1B | V192F | 1(0.03%)a | |||

Identified mutations are predicted to be damaging according to both SIFT and PolyPhen (accessed March 2012) or previous association with pediatric respiratory disease. Blank boxes indicate the mutations were not observed in that specific cohort.

Number (carrier frequency, assuming 1 mutation per individual).

Logistic regression models were used that included gestational age, gender, and mode of delivery, 3 covariates known to be associated with risk for RDS. We found that single ABCA3 mutations independently predicted risk for RDS among European-descent infants (odds ratio: 5.7 [95% confidence interval: 2.0–16.1]). Although gestational age was also an independent predictor of RDS (P < .001), further modeling did not detect a statistically significant interaction between presence of an ABCA3 mutation and gestational age (P = .43). Although the European-descent RDS infants had a lower mean gestational age than non-RDS infants (Table 1), there was no statistical difference in mean gestational age or birth weight for European-descent infants with or without ABCA3 mutations, thereby suggesting that ABCA3 mutations are associated with RDS rather than prematurity (Supplemental Table 11). In addition, no differences were found in measures of disease severity between European-descent RDS infants with and without an ABCA3 mutation, including duration of need for mechanical ventilation or supplemental oxygen, pneumothorax, need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, need for home oxygen, or death (Supplemental Table 12).

The estimated attributable risk of RDS associated with single ABCA3 mutations was 10.9% (95% confidence interval: 3.8–17.2) among European-descent infants ≥34 weeks’ gestation.

African-Descent Infants

The demographic characteristics of the Missouri population, the lower risk of RDS among African-descent infants,26 and our consecutive enrollment strategy limited access to a cohort of similar size as the European-descent cohort. There was no statistically significant overrepresentation of ABCA3 mutations among African-descent infants with RDS (4.5% of RDS infants vs 1.5% of non-RDS infants; P = .23) (Table 4); however, post-hoc analysis revealed our cohort was significantly underpowered (20% power, α = .05) to detect a difference. With 1 exception (c.4420C>T, p.R1474W), the ABCA3 mutations were unique to the African-descent disease-based infants (Tables 3 and 4). No mutations were detected in the remaining 4 genes among the African-descent disease-based infants.

TABLE 4.

Rare Mutations Identified Among Infants of African Descent

| Gene | Mutations | RDS (n = 44) | Non-RDS (n = 196) | Missouri Population (n = 195) | ESP (n = 1869) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCA3 | R20W | 2 | |||

| V129M | 12 | ||||

| F245L | 1 | ||||

| R280C | 1 | ||||

| R280H | 2 | ||||

| R288K | 7 (0.4%)a | ||||

| E292V | 4 (0.2%)a | ||||

| F353L | 3 | ||||

| N555S | 5 | ||||

| G571R | 1 | ||||

| T574I | 1 | 2 | |||

| P585S | 1 | ||||

| L707F | 14 | ||||

| G739A | 2 | 15 | |||

| V968M | 1 | 1 | |||

| F1164V | 1 | ||||

| N1418S | 1 | ||||

| R1474W | 1 | 1 | |||

| A1660V | 1 | ||||

| Infants with variant | 2 (4.5%)a | 3 (1.5%)a | 3 (1.5%)a | 72 (3.9%)a | |

| SFTPC | R35C | 1 | |||

| V39M | 1 | ||||

| G57S | 1 | ||||

| R81C | 1 | ||||

| SFTPC allele (carrier) frequency | 4 (0.2%)a | ||||

| CHPT1 | G70R | 2 | |||

| T87M | 1 | ||||

| G115A | 1 | ||||

| Y365H | 3 | ||||

| CHPT1 allele (carrier) frequency | 7 (0.4%)a | ||||

| LPCAT1 | A194V | 6 | |||

| L255Q | 2 | ||||

| D392H | 1 | ||||

| R526W | 1 | ||||

| LPCAT1 allele (carrier) frequency | 10 (0.5%)a | ||||

| PCYT1B | G199D | 1 (0.05%)a | |||

Identified mutations are predicted to be damaging according to both SIFT and PolyPhen (accessed March 2012) or previous association with pediatric respiratory disease. Blank boxes indicate the mutations were not observed in that specific cohort.

Number (carrier frequency).

Referred Infant Samples

We found that infants with single ABCA3 mutations were overrepresented among the European-descent (11 of 40 [27.5%]) and African-descent (1 of 8 [12.5%]) infants referred from other institutions (Supplemental Table 13). Only 1 of these infants was compound heterozygous for ABCA3 mutations (p.E292V/p.P933L) and therefore had ABCA3 deficiency. These data further support the observations from our cohort of infants with and without RDS.

Population-Based Cohort

The collapsed frequencies of ABCA3 mutations in the population-based and non-RDS cohorts were similar for both European-descent (3.6% vs 3.7%) and African-descent (1.5% [both]) infants (Tables 3 and 4). No infant in the population-based cohort had 2 ABCA3 mutations. To compare our ABCA3 mutation frequencies with an independent cohort, we used the same mutation selection strategy to interrogate the Exome Variant Server (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Exome Sequencing Project [ESP]),27 a database of >5400 individuals from up to 18 different US populations who participated in longitudinal cardiovascular- and pulmonary-related research. The collapsed carrier frequencies of ABCA3 mutations in both the ESP European-descent population and the African-descent population were similar to the Missouri cohort (European descent: 5.0% vs 3.6%, respectively [P = .07]; African descent: 3.9% vs 1.5%, respectively [P = .10]). The ESP database confirmed the very low frequencies of mutations in the other 4 surfactant-associated genes.

Discussion

ABCA3 mediates uptake of choline phospholipids and is required for lamellar body biogenesis.23 Studies in surrogate cell systems suggest that ABCA3 mutations impair surfactant metabolism by altering intracellular trafficking or folding of the ABCA3 protein or impairing ATP hydrolysis.28,29 Similar to other misfolded proteins, mutations in ABCA3 can also induce endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis.30 Infants with homozygous or compound heterozygous ABCA3 mutations develop progressive, lethal, neonatal-onset respiratory distress due to reduced phosphatidylcholine content and surface tension–lowering function of pulmonary surfactant.4,31 Our results suggest that term and late preterm European-descent infants with single ABCA3 mutations are at increased risk for non-lethal RDS. By selecting more mature (≥34 weeks’ gestation) infants who are less likely to suffer from developmental pulmonary immaturity, our cohort was enriched for infants with genetic causes of surfactant deficiency. In affected infants, single ABCA3 mutations may act independently or interact with other variants in key ABCA3 regulatory elements (promoter, introns, untranslated regions, synonymous variants, and large insertions or deletions) not covered by our sequencing or variant selection strategy,14,32,33 mutations in other genes,34 or other epigenetic, environmental, or developmental factors. Because ABCA3 expression is developmentally regulated,35 a single mutation coupled with developmental immaturity could reduce ABCA3 expression below a functional threshold that results in RDS. This speculation is supported by our referred group of infants and reports of premature infants with a single ABCA3 mutation with more severe disease than anticipated for gestational age.24,36 Similarly, individuals heterozygous for mutations in another ABC transporter ABCC7, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator, are at increased risk for chronic pancreatitis and rhinosinustitis,37,38 suggesting that even single alleles, typically expressed in a recessive fashion, may contribute to disease susceptibility.

The very low frequencies of mutations in SFTPB,11 SFTPC, PCYT1B, CHPT1, and LPCAT1 suggest significant negative selection pressure and nonredundant, critical functions for these proteins. The relatively common frequency of mutations in ABCA3 may reflect an unidentified, selective mutation advantage similar to the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator in which mutations may protect from bovine-transmitted infections39 or expression of molecules with redundant function (eg, ABCA1240). The similarity of the population-based and non-RDS ABCA3 mutation frequencies suggests that these 2 groups share a common genetic background. The lower frequency of ABCA3 mutations in the Missouri European and African-descent populations relative to the ESP database (3.6% vs 5.0% and 1.5% vs 3.9%, respectively), although not statistically significant, may reflect the variation of estimated mutation frequencies due to different sample sizes and/or differences in genetic admixture.41

We did not find a statistically significant overrepresentation of ABCA3 mutations among African-descent infants with RDS, which may be due to our cohort being underpowered. However, because African-descent populations are genetically more diverse than European populations,42,43 it is noteworthy that the prevalence of ABCA3 mutations among African-descent individuals was lower than among European-descent individuals, both in the Missouri population (1.5% vs 3.6%) and the ESP database (3.9% vs 5.0%), suggesting possible selection against disruptive mutations in this gene. In addition, we relied on maternally designated race for the disease-based cohort and population samples and may be underestimating genetic admixture, especially among African-descent individuals.44,45

Based on the frequency of ABCA3 mutations in the Missouri population and assuming recessive inheritance, we estimate the frequencies of ABCA3 deficiency at ∼1 in 3100 European-descent individuals and 1 in 18 000 African-descent individuals, which predicts ∼750 ABCA3-deficient individuals born annually in the United States. These frequencies are similar to cystic fibrosis (1 in 2500 European-descent infants and 1 in 15 000 African-descent infants).46 Although the true frequency of severe neonatal respiratory disease due to ABCA3 deficiency is unknown, <10 infants aged <1 year receive lung transplants each year in the United States for surfactant deficiency or neonatal-onset diseases.47 Thus, the phenotypes associated with ABCA3 deficiency may be unrecognized, may be lethal in utero, may not have pulmonary manifestations, or may present beyond the newborn period.5,23 The proportion of childhood or adult respiratory disease attributable to ABCA3 mutations is unknown.

Because we conservatively defined mutations, we may be misestimating the risk and frequency of disease attributable to single ABCA3 mutations. For example, although p.R1474W is predicted to be deleterious according to both SIFT and PolyPhen and has been detected in children with respiratory disease, its high carrier frequency (∼1%) and similar frequencies among infants with and without RDS suggest lower penetrance than estimated by the prediction algorithms. Conversely, our stringent computational criteria and biological precedent for mutation selection may discount important functional mutations and underestimate genetic contributions to respiratory disease. For example, p.R288K is predicted to be benign (tolerated) by both prediction algorithms and would not have been included in our analysis had it not been previously associated with pediatric respiratory disease.22 Its threefold to fourfold enrichment among the European-descent RDS infants suggests an important role in the genetic pathogenesis of RDS. In addition, some mutations predicted to be disruptive by computational algorithms may not impair protein function in vivo but may be protective or exhibit incomplete penetrance.

Functional studies of the >150 reported ABCA3 mutations in model systems are critical to understanding disease pathogenesis.26,41 Approximately 17 ABCA3 mutations have thus far been studied in vitro to determine the mechanisms that disrupt ABCA3 protein function or expression. Only 2 of these mutations were found in our study: p.R280C, which disrupts ABCA3 folding and trafficking, and p.E292V, which disrupts ATP hydrolysis and decreases phospholipid transport across the lamellar body membrane.29,30 Our combined genomic, computational, and disease-based variant discovery strategy permits prioritization of mutations for further functional investigation, which is critical for understanding disease pathogenesis.

Conclusions

Although homozygous or compound heterozygous ABCA3 mutations are well-established causes of lethal neonatal RDS, our study identified that single ABCA3 mutations are overrepresented among term and late preterm European-descent infants with RDS and account for ∼10.9% of the attributable risk for neonatal RDS. Although confounders may overestimate attributable risk, the high frequency of ABCA3 mutations among European-descent RDS term and late preterm infants suggests that these mutations account for a portion of disease heritability. Furthermore, ABCA3 mutations are collectively common in the general population, present in ∼4% of European- and African-descent individuals in the general population. Prospective evaluation of the predictive value of screening European-descent infants ≥34 weeks’ gestation for ABCA3 mutations might inform clinical assessment of genetic risk for RDS. Next generation, exome, or whole genome sequencing methods will permit more comprehensive genetic discovery of mutations that contribute to RDS heritability without the bias associated with a candidate gene approach.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute GO Exome Sequencing Project and its ongoing studies, which produced and provided exome variant calls for comparison: the Lung GO Sequencing Project (HL-102923), the WHI Sequencing Project (HL-102924), the Broad GO Sequencing Project (HL-102925), the Seattle GO Sequencing Project (HL-102926), and the Heart GO Sequencing Project (HL-103010). The authors acknowledge Leslie Walther, RN, and Rosina Schiff, BS, for their significant contributions to patient recruitment.

Glossary

- ESP

Exome Sequencing Project

- RDS

respiratory distress syndrome

- SIFT

Sorting Intolerant From Intolerant

- SPLINTER

short indel prediction by large deviation inference and nonlinear true frequency estimation by recursion

Footnotes

Dr Wambach, Mr Wegner, Dr Druley, Dr Mitra, Dr Cole, and Dr Hamvas were responsible for study conception and design; Dr Wambach, Mr Wegner, Ms DePass, Ms Heins, Dr Druley, Dr Mitra, Dr Cole, and Dr Hamvas performed acquisition of data; Dr Wambach, Mr Wegner, Ms DePass, Dr An, Dr Zhang, Dr Nogee, Dr Cole, and Dr Hamvas conducted analysis and interpretation of data; all authors were responsible for drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and all authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: Mr Wegner, Ms DePass, Ms Heins, Dr An, and Dr Zhang have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. Drs Wambach, Druley, Mitra, Nogee, Cole, and Hamvas received funding from the National Institutes of Health. Drs Druley and Mitra received funding from the Children's Discovery Institute (St Louis Children's Hospital/Washington University). Dr Nogee received funding from the Eudowood Foundation. Drs Cole and Hamvas received funding from the Saigh Foundation. Dr Mitra received funding from Kailos Genetics. Kailos Scientific has licensed 1 of Dr Mitra's patents, and Dr Mitra serves on their scientific advisory board. Kailos Scientific makes reagents for creating libraries for next-generation sequencing; although these reagents were not used in this study, next-generation sequencing was performed. Dr Wambach, Mr Wegner, Ms DePass, Ms Heins, Dr Druley, Dr An, Dr Zhang, Dr Nogee, Dr Cole, and Dr Hamvas have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FUNDING: Funding was received from the National Institutes of Health: R01 HL065174 (Drs Cole and Hamvas), R01 HL082747 (Drs Cole and Hamvas), K12 HL089968 (Dr Cole), K08 HL105891 (Dr Wambach), R01 HL054703 (Dr Nogee), and K08 CA140720-01A1 (Dr Druley). Funding was also received from the Eudowood Foundation (Dr Nogee); the Children’s Discovery Institute (Dr Mitra and Dr Druley); the Saigh Foundation (Drs Cole and Hamvas); and Kailos Genetics (Dr Mitra). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found on page e1677, and online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2012-2870.

References

- 1.Barber M, Blaisdell CJ. Respiratory causes of infant mortality: progress and challenges. Am J Perinatol. 2010;27(7):549–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levit O, Jiang Y, Bizzarro MJ, et al. The genetic susceptibility to respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2009;66(6):693–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Sonderen L, Halsema EF, Spiering EJ, Koppe JG. Genetic influences in respiratory distress syndrome: a twin study. Semin Perinatol. 2002;26(6):447–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shulenin S, Nogee LM, Annilo T, Wert SE, Whitsett JA, Dean M. ABCA3 gene mutations in newborns with fatal surfactant deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(13):1296–1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nogee LM, Dunbar AE, III, Wert S, Askin F, Hamvas A, Whitsett JA. Mutations in the surfactant protein C gene associated with interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2002;121(suppl 3):20S–21S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nogee LM, Wert SE, Proffit SA, Hull WM, Whitsett JA. Allelic heterogeneity in hereditary surfactant protein B (SP-B) deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(3 pt 1):973–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Floros J, Thomas NJ, Liu W, et al. Family-based association tests suggest linkage between surfactant protein B (SP-B) (and flanking region) and respiratory distress syndrome (RDS): SP-B haplotypes and alleles from SP-B-linked loci are risk factors for RDS. Pediatr Res. 2006;59(4 pt 1):616–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lahti M, Marttila R, Hallman M. Surfactant protein C gene variation in the Finnish population—association with perinatal respiratory disease. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12(4):312–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodmer W, Bonilla C. Common and rare variants in multifactorial susceptibility to common diseases. Nat Genet. 2008;40(6):695–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li B, Leal SM. Methods for detecting associations with rare variants for common diseases: application to analysis of sequence data. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83(3):311–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamvas A, Wegner DJ, Carlson CS, et al. Comprehensive genetic variant discovery in the surfactant protein B gene. Pediatr Res. 2007;62(2):170–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamvas A, Heins HB, Guttentag SH, et al. Developmental and genetic regulation of human surfactant protein B in vivo. Neonatology. 2009;95(2):117–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.St Clair C, Norwitz ER, Woensdregt K, et al. The probability of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome as a function of gestational age and lecithin/sphingomyelin ratio. Am J Perinatol. 2008;25(8):473–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wambach JA, Yang P, Wegner DJ, et al. Surfactant protein-C promoter variants associated with neonatal respiratory distress syndrome reduce transcription. Pediatr Res. 2010;68(3):216–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Druley TE, Vallania FL, Wegner DJ, et al. Quantification of rare allelic variants from pooled genomic DNA. Nat Methods. 2009;6(4):263–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamvas A, Trusgnich M, Brice H, et al. Population-based screening for rare mutations: high-throughput DNA extraction and molecular amplification from Guthrie cards. Pediatr Res. 2001;50(5):666–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bridges JP, Ikegami M, Brilli LL, Chen X, Mason RJ, Shannon JM. LPCAT1 regulates surfactant phospholipid synthesis and is required for transitioning to air breathing in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(5):1736–1748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vallania FL, Druley TE, Ramos E, et al. High-throughput discovery of rare insertions and deletions in large cohorts. Genome Res. 2010;20(12):1711–1718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3812–3814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sunyaev S, Ramensky V, Koch I, Lathe W, III, Kondrashov AS, Bork P. Prediction of deleterious human alleles. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(6):591–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benichou J. Methods of adjustment for estimating the attributable risk in case-control studies: a review. Stat Med. 1991;10(11):1753–1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brasch F, Schimanski S, Mühlfeld C, et al. Alteration of the pulmonary surfactant system in full-term infants with hereditary ABCA3 deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(5):571–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bullard JE, Wert SE, Whitsett JA, Dean M, Nogee LM. ABCA3 mutations associated with pediatric interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(8):1026–1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garmany TH, Wambach JA, Heins HB, et al. Population and disease-based prevalence of the common mutations associated with surfactant deficiency. Pediatr Res. 2008;63(6):645–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agrawal A, Hamvas A, Cole FS, et al. An intronic ABCA3 mutation that is responsible for respiratory disease. Pediatr Res. 2012;71(6):633–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kavvadia V, Greenough A, Dimitriou G, Hooper R. Influence of ethnic origin on respiratory distress syndrome in very premature infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1998;78(1):F25–F28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Exome Variant Server, NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA. Available at: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/. Accessed March 1, 2012

- 28.Matsumura Y, Ban N, Ueda K, Inagaki N. Characterization and classification of ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA3 mutants in fatal surfactant deficiency. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(45):34503–34514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsumura Y, Ban N, Inagaki N. Aberrant catalytic cycle and impaired lipid transport into intracellular vesicles in ABCA3 mutants associated with nonfatal pediatric interstitial lung disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295(4):L698–L707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weichert N, Kaltenborn E, Hector A, et al. Some ABCA3 mutations elevate ER stress and initiate apoptosis of lung epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2011;12:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garmany TH, Moxley MA, White FV, et al. Surfactant composition and function in patients with ABCA3 mutations. Pediatr Res. 2006;59(6):801–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheridan MB, Hefferon TW, Wang N, et al. CFTR transcription defects in pancreatic sufficient cystic fibrosis patients with only one mutation in the coding region of CFTR. J Med Genet. 2011;48(4):235–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen R, Davydov EV, Sirota M, Butte AJ. Non-synonymous and synonymous coding SNPs show similar likelihood and effect size of human disease association. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(10):e13574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bullard JE, Nogee LM. Heterozygosity for ABCA3 mutations modifies the severity of lung disease associated with a surfactant protein C gene (SFTPC) mutation. Pediatr Res. 2007;62(2):176–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stahlman MT, Besnard V, Wert SE, et al. Expression of ABCA3 in developing lung and other tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2007;55(1):71–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park SK, Amos L, Rao A, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel ABCA3 mutation. Physiol Genomics. 2010;40(2):94–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X, Moylan B, Leopold DA, et al. Mutation in the gene responsible for cystic fibrosis and predisposition to chronic rhinosinusitis in the general population. JAMA. 2000;284(14):1814–1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohn JA, Friedman KJ, Noone PG, Knowles MR, Silverman LM, Jowell PS. Relation between mutations of the cystic fibrosis gene and idiopathic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(10):653–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alfonso-Sánchez MA, Pérez-Miranda AM, García-Obregón S, Peña JA. An evolutionary approach to the high frequency of the Delta F508 CFTR mutation in European populations. Med Hypotheses. 2010;74(6):989–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yanagi T, Akiyama M, Nishihara H, et al. Harlequin ichthyosis model mouse reveals alveolar collapse and severe fetal skin barrier defects. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(19):3075–3083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kruglyak L, Nickerson DA. Variation is the spice of life. Nat Genet. 2001;27(3):234–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tishkoff SA, Reed FA, Friedlaender FR, et al. The genetic structure and history of Africans and African Americans. Science. 2009;324(5930):1035–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang L, Jakobsson M, Pemberton TJ, et al. Haplotype variation and genotype imputation in African populations. Genet Epidemiol. 2011;35(8):766–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patterson N, Hattangadi N, Lane B, et al. Methods for high-density admixture mapping of disease genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74(5):979–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith MW, Patterson N, Lautenberger JA, et al. A high-density admixture map for disease gene discovery in African Americans. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74(5):1001–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cystic Fibrosis Clinical Validity. National Office of Public Health Genomics. September 10, 2007

- 47.Aurora P, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirteenth official pediatric lung and heart-lung transplantation report—2010. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29(10):1129–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.