Abstract

The discovery of microRNAs (miRNAs) almost two decades ago established a new paradigm of gene regulation. During the past ten years these tiny non-coding RNAs have been linked to virtually all known physiological and pathological processes, including cancer. In the same way as certain key protein-coding genes, miRNAs can be deregulated in cancer, in which they can function as a group to mark differentiation states or individually as bona fide oncogenes or tumour suppressors. Importantly, miRNA biology can be harnessed experimentally to investigate cancer phenotypes or used therapeutically as a target for drugs or as the drug itself.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, evolutionarily conserved, non-coding RNAs of 18–25 nucleotides in length that have an important function in gene regulation. Mature miRNA products are generated from a longer primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) transcript through sequential processing by the ribonucleases Drosha and Dicer1 (ref. 1). The first description of miRNAs was made in 1993 in Caenorhabditis elegans as regulators of developmental timing2,3. Later, miRNAs were shown to inhibit their target genes through sequences that are complementary to the target messenger RNA, leading to decreased expression of the target protein1 (Box 1). This discovery resulted in a pattern shift in our understanding of gene regulation because miRNAs are now known to repress thousands of target genes and coordinate normal processes, including cellular proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. The aberrant expression or alteration of miRNAs also contributes to a range of human pathologies, including cancer.

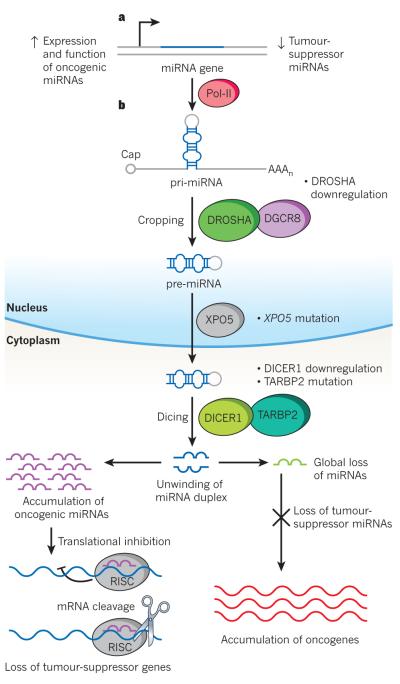

BOX 1. Biogenesis and function of miRNAs.

miRNAs are subjected to a unique biogenesis that is closely related to their regulatory functions. As the pathway in Fig. 1 shows, in general miRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II into primary transcripts called pri-miRNAs76. The primary transcripts contain a 5′ cap structure a poly(A)+ tail and may include introns, similar to the transcripts of protein-coding genes76. They also contain a region in which the sequences are not perfectly complementary, known as the stem–loop structure, which is recognized in the nucleus by the ribonuclease Drosha and its partner DGCR8, giving rise to the precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) by cropping76. However, some intronic miRNAs (called mirtrons) bypass the Drosha processing step and, instead, use splicing machinery to generate the pre-miRNA99. The pre-miRNA is exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm by XPO5 and is further cleaved by the ribonuclease Dicer1 (along with TARBP2) into a double-stranded miRNA (process known as dicing)76. Again, this cleavage can be substituted by Argonaute-2-mediated processing100.

After strand separation, the guide strand or mature miRNA forms, in combination with Argonaute proteins, the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), whereas the passenger strand is usually degraded. The mature strand is important for specific-target mRNA recognition and its consequent incorporation into the RISC1. The specificity of miRNA targeting is defined by how complementary the ‘seed’ sequence (positions 2 to 8 from the 5′ end of the miRNA) and the ‘seed-match’ sequence (generally in the 3′ untranslated region of the target mRNA) are. The expression of the target mRNAs is silenced by miRNAs, either by mRNA cleavage (‘slicing’) or by translational repression1. In addition, miRNAs have a number of unexpected functions, including the targeting of DNA, ribonucleoproteins or increasing the expression of a target mRNA93. Overall, data indicate the complexity of miRNA-mediated gene regulation and highlight the importance of a better understanding of miRNA biology.

The control of gene expression by miRNAs is a process seen in virtually all cancer cells. These cells show alterations in their miRNA expression profiles, and emerging data indicate that these patterns could be useful in improving the classification of cancers and predicting their behaviour. In addition, miRNAs have now been shown to behave as cancer ‘drivers’ in the same way as protein-coding genes whose alterations actively and profoundly contribute to malignant transformation and cancer progression. Owing to the capacity of miRNAs to modulate tens to hundreds of target genes, they are emerging as important factors in the control of the ‘hallmarks’ of cancer4. In this Review, we summarize the findings that provide evidence for the central role of miRNAs in controlling cellular transformation and tumour progression. We also highlight the potential uses of miRNAs and miRNA-based drugs in cancer therapy and discuss the obstacles that will need to be overcome.

miRNAs are cancer genes

In 2002, Croce and colleagues first demonstrated that an miRNA cluster was frequently deleted or downregulated in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia5. This discovery suggested that non-coding genes were contributing to the development of cancer, and paved the way for the closer investigation of miRNA loss or amplification in tumours. Subsequently, miRNAs were shown to be differentially expressed in cancer cells, in which they formed distinct and unique miRNA expression patterns6, and whole classes of miRNAs could be controlled directly by key oncogenic transcription factors7. In parallel, studies with mouse models established that miRNAs were actively involved in tumorigenesis8. Collectively, these findings provided the first key insights into the relevance of miRNA biology in human cancer.

Despite these results, the sheer extent of involvement of miRNAs in cancer was not anticipated. miRNA genes are usually located in small chromosomal alterations in tumours (in amplifications, deletions or linked to regions of loss of heterozygosity) or in common chromosomal-breakpoints that are associated with the development of cancer9. In addition to structural genetic alterations, miRNAs can also be silenced by promoter DNA methylation and loss of histone acetylation10. Interestingly, somatic translocations in miRNA target sites can also occur, representing a drastic means of altering miRNA function11,12. The frequent deregulation of individual or clusters of miRNAs at multiple levels mirrors the deregulation for protein-coding oncogenes or tumour suppressors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key microRNAs involved in cancer

| MicroRNA | Function | Genomic location |

Mechanism | Targets | Cancer type | Mouse models | Clinical application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-17-92 cluster |

Oncogene | 13q22 | Amplification and transcriptional activation |

BIM, PTEN, CDKN1A and PRKAA1 |

Lymphoma, lung, breast, stomach, colon and pancreatic cancer |

Cooperates with MYC to produce lymphoma. Overexpression induces lymphoproliferative disease |

Inhibition and detection |

| miR-155 | Oncogene | 21q21 | Transcriptional activation |

SHIP1 and CEBPB |

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, lymphoma, lung, breast and colon cancer |

Overexpression induces pre-B-cell lymphoma and leukaemia |

Inhibition and detection |

| miR-21 | Oncogene | 17q23 | Transcriptional activation |

PTEN, PDCD4 and TPM1 |

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, acute myeloid leukaemia, glioblastoma, pancreatic, breast, lung, prostate, colon and stomach cancer |

Overexpression induces lymphoma |

Inhibition and detection |

| miR- 15a/16-1 |

Tumour suppressor |

13q31 | Deletion, mutation and transcriptional repression |

BCL2 and MCL1 |

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, prostate cancer and pituitary adenomas |

Deletion causes chronic lymphocytic leukaemia |

Expression with mimics and viral vectors |

| let-7 family | Tumour suppressor |

11 copies (multiple locations) |

Transcriptional repression |

KRAS, MYC and HMGA2 |

Lung, colon, stomach, ovarian and breast cancer |

Overexpression suppresses lung cancer |

Expression with mimics and viral vectors |

| miR-34 family |

Tumour suppressor |

1p36 and 11q23 |

Epigenetic silencing, transcriptional repression and deletion |

CDK4, CDK6, MYC and MET |

Colon, lung, breast, kidney, bladder cancer, neuroblastoma and melanoma |

No published studies | Expression with mimics and viral vectors |

| miR-29 family |

Oncogene | 7q32 and 1q30 |

Transcriptional activation |

ZFP36 | Breast cancer and indolent chronic lymphocytic leukaemia |

Overexpression induces chronic lymphocytic leukaemia |

No published studies |

| Tumour suppressor |

Deletion and transcriptional repression |

DNMTs | Acute myeloid leukaemia, aggressive chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and lung cancer |

No published studies |

BCL2, B-cell lymphoma protein-2; BIM, BCL-2-interactiing mediator of cell death; CDKN1A, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A; CEBPB, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β; HMGA2, high mobility group AT-hook 2; CDK4, cyclin-dependent kinase 4; CDK6, cyclin-dependent kinase 6; DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; MCL1, myeloid cell leukaemia sequence 1; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homologue; PRKAA1, protein kinase, AMP-activated, alpha 1 catalytic subunit; PDCD4, programmed cell death 4; SHIP1, Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol 5-phosphatase 1; TPM1, tropomyosin 1; ZFP36, zinc finger protein 36.

In principle, somatic mutations that change an miRNA seed sequence could lead to the aberrant repression of tumour-suppressive mRNAs, but these seem to be infrequent13. Further sequencing could change this view, but this observation suggests that the intensity of miRNA signalling (altered by miRNA overexpression or underexpression) is more crucial than the specificity of the response. However, recent data indicate that miRNAs with an altered sequence can be produced through variable cleavage sites for Drosha and Dicer1, and that the presence of these variants can be perturbed in cancer14. Although the function of the variant ‘isomiRs’ remains unclear, in principle they could alter the quality of miRNA effects. State-of-the-art sequencing techniques will help to unmask mutations or modifications that otherwise would remain undetected. Whatever the mechanism, the widespread alteration in the expression of miRNAs is a ubiquitous feature of cancer.

miRNAs as cancer classifiers

Aberrant miRNA levels reflect the physiological state of cancer cells and can be detected by miRNA expression profiling and harnessed for the purpose of diagnosis and prognosis15,16. In fact, miRNA profiling can be more accurate at classifying tumours than mRNA profiling because miRNA expression correlates closely with tumour origin and stage, and can be used to classify poorly differentiated tumours that are difficult to identify using a standard histological approach6,17. Whether or not this increased classification power relates to the biology of miRNAs or the reduced complexity of the miRNA genome still needs to be determined.

The special features of miRNAs make them potentially useful for detection in clinical specimens. For example, miRNAs are relatively resistant to ribonuclease degradation, and they can be easily extracted from small biopsies, frozen samples and even formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues18 . Furthermore, relatively simple and reproducible assays have been developed to detect the abundance of individual miRNAs, and methods that combine small RNA isolation, PCR and next-generation sequencing, allow accurate and quantitative assessment of all the miRNAs that are expressed in a patient specimen, including material that has been isolated by laser capture microdissection. The detection of global miRNA expression patterns for the diagnosis of cancers has not yet been proved; however, some individual or small groups of miRNAs have shown promise. For example, in non-small cell lung cancer, the combination of high miR-155 and low let-7 expression correlates with a poor prognosis, and in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia a 13 miRNA signature is associated with disease progression15,16. Further advances in the technology of miRNA profiling could help to revolutionize molecular pathology.

Perhaps the most appealing application of miRNAs as a cancer diagnostic tool comes from the discovery of circulating miRNAs in serum. For example, miR-141 expression levels in serum were significantly higher in patients with prostate cancer than in healthy control individuals19. Although the analysis of circulating miRNAs is only just beginning, the successful advancement of this technology could provide a relatively non-invasive diagnostic tool for single-point or longitudinal studies. With such diagnostic tools in place, miRNA profiling could be used to guide cancer classification, facilitate treatment decisions, monitor treatment efficacy and predict clinical outcome.

When miRNA biogenesis goes awry

Although the expression of some miRNAs is increased in malignant cells, the widespread underexpression of miRNAs is a more common phenomenon. Whether this tendency is a reflection of a pattern associated with specific cells of origin, is a consequence of the malignant state or actively contributes to cancer development is still unclear. Because miRNA expression generally increases as cells differentiate, the apparent underexpression of miRNAs in cancer cells may, in part, be a result of miRNAs being ‘locked’ in a less-differentiated state. Alternatively, changes in oncogenic transcription factors that repress miRNAs or variability in the expression or activity of the miRNA processing machinery could also be important.

Two main mechanisms have been proposed as the underlying cause of the global downregulation of miRNAs in cancer cells. One involves transcriptional repression by oncogenic transcription factors. For example, the MYC oncoprotein, which is overexpressed in many cancers, transcriptionally represses certain miRNAs, although the extent to which this mediates its oncogenic activity or reflects a peripheral effect is still unknown20. The other mechanism proposed involves changes in miRNA biogenesis and is based on the observation that cancer cells often display reduced levels, or altered activity, of factors in the miRNA biogenesis pathway21 (Box 1, Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Mechanisms of miRNA perturbation in cancer.

Cancer cells present global downregulation of miRNAs, loss of tumour-suppressor miRNAs and specific accumulation of oncogenic miRNAs. The alteration in miRNA expression patterns leads to the accumulation of oncogenes and downregulation of tumour-suppressor genes, which leads to the promotion of cancer development. a, The expression and function of oncogenic miRNAs is increased by genomic amplification, activating mutations, loss of epigenetic silencing and transcriptional activation. By contrast, tumour-suppressor miRNAs are lost by genomic deletion, inactivating mutations, epigenetic silencing or transcriptional repression. b, After transcription, global levels of miRNAs can be reduced by impaired miRNA biogenesis. Inactivating mutations and reduced expression have been described for almost all the members of the miRNA processing machinery. If there is a downreguation of DROSHA this can lead to a decrease in the cropping of primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) to precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA). In the case of XPO5 mutation, pre-miRNAs are prevented from being exported to the cytoplasm. Mutation of TARBP2 or downregulation of DICER1 results in a decrease in mature miRNA levels. Pol II, RNA polymerase II; RISC, RNA-induced silencing complex.

In vivo studies have provided the most direct evidence of an active role for miRNA downregulation in at least some types of cancer. For example, analysis of mouse models in which the core enzymes of miRNA biogenesis have been constitutively or conditionally disrupted by different mechanisms suggests that these molecules function as haploinsufficient tumour suppressors. Thus, the repression of miRNA processing by the partial depletion of Dicer1 and Drosha accelerates cellular transformation and tumorigenesis in vivo22. Furthermore, deletion of a single Dicer1 allele in lung epithelia promotes Kras-driven lung adenocarcinomas, whereas complete ablation of Dicer1 causes lethality because of the need for miRNAs in essential processes23. Consistent with the potential relevance of these mechanisms, reduced Dicer1 and Drosha levels have been associated with poor prognosis in the clinic24. In addition to the core machinery, modulators of miRNA processing can also function as haploinsufficient tumour suppressors. Hence, point mutations that affect TARBP2 or XPO5 are correlated with sporadic and hereditary carcinomas that have microsatellite instability25,26. Other miRNA modulators that influence the processing of only a subset of miRNAs could also be important. For example, LIN28A and LIN28B can bind and repress members of the let-7 family (which are established tumour-suppressor miRNAs; Table 1), but this binding can be counteracted by KHSRP (KH-type splicing regulatory protein), also a factor involved in miRNA biogenesis; together this binding and counteracting dictate the level of mature let-7. The processing of miRNAs can be regulated by other genes including DDX5 (helicase p68) or the SMAD 1 and SMAD 5 proteins, which may contribute to cancer development through the deregulation of miRNAs27. Collectively, the global changes in miRNA expression that are seen in cancer cells probably arise through multiple mechanisms; the combined small changes in the expression of many miRNAs seem to have a large impact on the malignant state.

miRNAs as cancer drivers

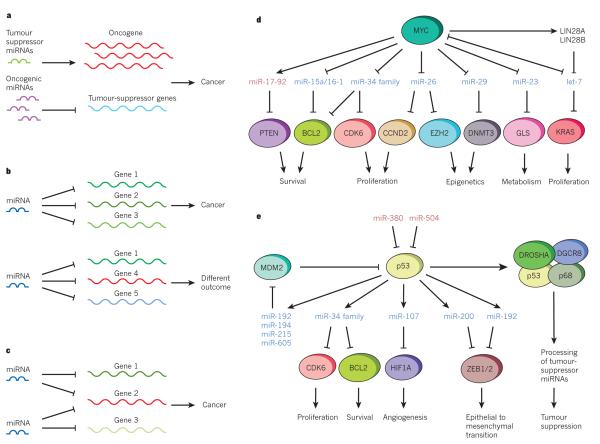

Functional studies show that miRNAs that are affected by somatic alterations in tumours can affect cancer phenotypes directly, therefore confirming their driver function in malignancy. As drivers of malignancy, mechanistic studies show that these miRNAs interact with known cancer networks; hence, tumour-suppressor miRNAs can negatively regulate protein-coding oncogenes, whereas oncogenic miRNAs often repress known tumour suppressors (Fig. 2a). Perhaps the best example of this is the oncogenic miR-17-92 cluster, in which individual miRNAs suppress negative regulators of phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase signalling or pro-apoptotic members of the BCL-2 family, which disrupts the processes that are known to influence cancer development28 (Table 1).

Figure 2. Contribution of miRNAs to cancer pathways.

a, Tumour-suppressor miRNAs, which repress oncogenes in healthy cells, are lost in cancer cells, leading to oncogene upregulation, whereas oncogenic miRNAs inhibit tumour-suppressor genes, giving rise to cancer. b, The presence of different target genes in different cell lines can modify the function of an miRNA, both in healthy cells and cancer cells, which can lead to the development of cancer or a different outcome. c, Two miRNAs can function together to regulate one or several pathways, which reinforces those pathways and can result in the development of cancer. d, The oncogene MYC can either repress tumour-suppressor miRNAs (in blue) or activate oncogenic miRNAs (in red) and can therefore orchestrate several different pathways. MYC can repress let-7, directly, or indirectly, through LIN28 activation. Conversely, let-7 can also repress MYC, which closes the regulatory circle. e, Tumour suppressor p53 can regulate several tumour suppressor miRNAs (blue), activating different antitumoral pathways. The regulation of MDM2 by some of these miRNAs leads to interesting feedforward loops. At the same time, p53 can be negatively regulated by oncogenic miRNAs (in red). In addition, p53 is involved in the biogenesis of several tumour suppressor miRNAs.

Cancer-associated miRNAs can also alter the epigenetic landscape of cancer cells. The cancer ‘epigenome’ is characterized by global and gene-specific changes in DNA methylation, histone modification patterns and chromatin-modifying enzyme expression profiles, which impact gene expression in a heritable way29. In one way, miRNA expression can be altered by DNA methylation or histone modifications in cancer cells10,30, but miRNAs can also regulate components of the epigenetic machinery, therefore indirectly contributing to the reprogramming of cancer cells. For example, miR-29 inhibits DNMT3A DNMT3B expression in lung cancer31, whereas miR-101 regulates the histone methyltransferase EZH2 in prostate cancer32. The presence of mature miRNAs in the nucleus33 is another indication of the potentially direct role that miRNAs have in controlling epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications — a hypothesis that has been established in plants34 but still needs to be demonstrated with certainty in mammals.

In the same way as protein-coding genes, miRNAs can be oncogenes or tumour suppressors depending on the cellular context in which they are expressed, which means that defining their precise contribution to cancer can be a challenge (Fig. 2b). The fact that miRNAs show tissue-specific expression and their output, shown in the cell’s physiology, is dependent on the expression pattern of the specific mRNAs that harbour target sites could explain this apparent paradox. For example, the miR-29 family has a tumour-suppressive effect in lung tumours but appears oncogenic in breast cancer because of its ability to target the DNA methyltransferases DNMT3A and DNMT3B, and ZFP36, respectively31,35 (Table 1).

To further complicate the process, some miRNAs repress several positive components of a pathway, whereas others target both positive and negative regulators, possibly to buffer against minor physiological variations that could trigger much larger changes in the cell physiology36 In cancer cells, this buffering role can mean that some miRNAs could simultaneously target oncogenes and tumour-suppressor genes. In addition, combinations of miRNAs can cooperate to regulate one or several pathways, which increases the flexibility of regulation but confounds experimentalists37 (Fig. 2c). Consequently, the way in which miRNAs contribute to cancer development is conceptually similar to cancer-associated transcription factors such as MYC and p53, which are mediated through many targets that depend on contextual factors that are influenced by cell type and micro-environment. From a practical perspective it is crucial that miRNA targets are studied in a context that is appropriate to the environment that is being studied to determine what impact they will have on tumour cell behaviour (Fig. 2b).

Oncogenic pathways

Beyond the impact of somatic genetic and epigenetic lesions, the altered expression of miRNAs in cancer can arise through the aberrant activity of transcription factors that control their expression. Interestingly, the same transcription factors are often targets of miRNA-mediated repression, which gives rise to complex regulatory circuits and feedback mechanisms. Thus, a single transcription factor can activate or repress several miRNAs and protein-coding genes; in turn, the alteration in miRNA expression can affect more protein-coding genes that then amplifies the effects of a single gene.

As already mentioned, MYC directly contributes to the global transcriptional silencing of miRNAs20. This repression involves the downregulation of miRNAs with antiproliferative, antitumorigenic and pro-apoptotic activity such as, let-7, miR-15a/16-1, miR-26a or miR-34 family members38 (Fig. 2d; Table 1). Initial studies indicate that Myc uses both transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms to modulate miRNA expression. This phenomenon could be due to LIN28A and LIN28B being the direct target of MYC, and that they are required for MYC-mediated repression of let-7 (ref. 38). Furthermore, MYC directly activates the transcription of miR-17-92 polycistronic cluster and, given its oncogenic role, it may contribute to MYC-induced tumorigenesis39.

MYC-driven reprogramming of miRNA expression could also be a factor in hepatocellular carcinoma, because of the contribution the reprogramming has to the aggressive phenotype of tumours originating from hepatic progenitor cells40. Some miRNAs, such as let-7, also regulate MYC, closing the regulatory circuit37.

miRNAs are embedded in many other oncogenic networks, including KRAS activation, which leads to the repression of several miRNAs. For example, in pancreatic cancer with mutant KRAS, RAS-responsive element-binding protein 1 (RREB1) represses miR-143 and miR-145 promoter, and at the same time both KRAS and RREB1 are targets of miR-143 and miR-145, revealing a feedforward mechanism that increases the effect of RAS signalling41. Similarly, KRAS is a target for several miRNAs, of which the let-7 family is the most representative example42. The integration of miRNAs into key oncogenic pathways, and the generation of feedforward and feedback loops that have a balancing effect, creates intricate ways to incorporate intracellular and extracellular signals in the decisions of cell proliferation or survival, and further implicates miRNAs in the pathogenesis of cancer.

TP53 is a master regulator of miRNAs

The TP53 tumour suppressor is perhaps the most important and well-studied cancer gene, and it is not surprising that several studies have suggested that miRNA biology can have a role in its regulation and activity (Fig. 2e). The p53 protein acts as a sequence-specific DNA-binding factor that can activate and repress transcription. Although there is no doubt that most of the actions of p53 can be explained by its ability to control canonical protein-coding targets such as CDKN1A and PUMA, it can also transactivate several miRNAs. One of the best-studied classes is the miR-34 family (Table 1), which represses genes that can promote proliferation and apoptosis — plausible targets in a p53-mediated tumour-suppressor response43. In principle, the action of p53 to induce the expression of miR-34 and other miRNAs can explain some of its transcriptional repressive functions.

The discovery of additional p53-regulated miRNAs, and the targeting of p53 or its pathway by other miRNAs, has provided general insights into the miRNA-mediated control of gene expression and the potential therapeutic opportunities for targeting the p53 network (Fig. 2e). Several p53-activated miRNAs, such as miR-192, miR-194, miR-215 and miR-605, can target MDM2, which is a negative regulator of p53 and a therapeutic target. These potentially relevant miRNAs can be epigenetically silenced in some types of cancer; however, their reactivation or reintroduction (see the section miRNAs as drugs and drug targets) offers an intriguing therapeutic opportunity for inhibiting MDM2 in tumours that harbour wild-type p53 (refs 44, 45). Similarly, p53 can also activate miR-107, miR-200 or miR-192, which are miRNAs that inhibit angiogenesis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition46–48. Conversely, p53 can be repressed by certain oncogenic miRNAs including miR-380-5p, which is upregulated in neuroblastomas with MYCN amplification, or miR-504, which decreases p53-mediated apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest and can promote tumorigenesis49,50. However, the extent to which these miRNAs control life and death decisions in the p53 network still needs to be shown decisively to determine whether these miRNAs are valid therapeutic targets.

The studies mentioned have extended our understanding of the roles and regulation of p53 into the world of small non-coding RNAs, but the action on miRNA biology may be even more complex. For example, one study51 suggests that p53 can affect miRNA biogenesis by promoting pri-miRNA processing through association with the large Drosha complex (Fig. 2e), but the precise mechanism remains unclear51. In a more conventional way, the p53 family member p63 transcriptionally controls Dicer1 expression. Mutant TP53 can interfere with this regulation, which leads to a reduction in Dicer1 levels and reduces the levels of certain cancer-relevant miRNAs52. Thus, with the p53 network as a typical example, it is clear that miRNAs can interact with cancer-relevant pathways at multiple and unexpected levels and that a better understanding of miRNA biology will help to decipher the role and function of other important cancer genes.

Micromanagement of metastasis and beyond

In addition to promoting cancer initiation, miRNAs can modulate processes that support cancer progression, including metastasis53–56. As indicated earlier, changes in miRNA levels can occur through effects on their transcription or by global changes in the RNA interference (RNAi) machinery, and both mechanisms seem to be important for this process. For example, in breast cancer, miR-10b and miR-9 can induce metastasis, whereas miR-126, miR-335 and miR-31 act as suppressors. The miR-200 family inhibits epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, which influences one aspect of the metastatic process57. However, miR-200 could also promote the colonization of metastatic cells in breast cancer, which provides yet another example of the opposing activities of some miRNAs58. Conversely, in head and neck squamous-cell carcinomas, lung adenocarcinomas and breast cancers, the reduced levels of certain miRNAs that arise from Dicer1 downregulation also promote cell motility and are associated with enhanced metastasis in experimental models52,59.

The pleiotropic effects of miRNA biology on cancer extend to virtually all acquired cancer traits, including cancer-associated changes in intracellular metabolism and the tissue microenvironment. For example, most cancer cells display alterations in glucose metabolism termed the Warburg effect60. miRNAs may contribute to this metabolic switch because, in glioma cells, miR-451 controls cell proliferation, migration and responsiveness to glucose deprivation, thereby allowing the cells to survive metabolic stress61. The enhanced glutaminolysis observed in cancer cells can be partially explained by MYC-mediated repression of miR-23a and miR-23b (ref. 62) (Fig. 2d). In some cases, the control of these cancer-related processes by miRNAs creates an opportunity for new therapeutic approaches. Hence, miR-132, which is present in the endothelium of tumours but not in normal human endothelium, induces neovascularization by inhibition of p120RasGAP, a negative regulator of KRAS63. The delivery of a miR-132 inhibitor with nanoparticles that target the tumour vasculature suppresses angiogenesis in mice; this indicates there is a potential for the development of new antiangiogenic drugs. Further studies are likely to implicate miRNAs in the modulation of every tumour-associated pathway or trait.

Big lessons from mice

Much of what we have learnt concerning the functional contribution of miRNA biology to cancer development comes from studies in genetically engineered mice. These systems provide powerful tools for the genetic and biological study of miRNAs in an in vivo context, which is particularly important given the contextual activity of most miRNAs. In addition, owing to the ability of these models to recapitulate the behaviour of some human malignancies, they are useful in preclinical studies to evaluate new therapeutics.

Perhaps the most widespread use of mice for characterizing miRNA biology in cancer is the validation of miRNAs that are altered in cancer cells, as bona fide oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes. As already mentioned, the first direct evidence that miRNAs have a function in cancer came from mouse models, in which it was shown that expression of the miR-17-92 cluster — which is amplified in some human B cell lymphomas — cooperates with Myc to promote B-cell lymphoma in mice8. Subsequent studies that have used genetically engineered or transplantation-based systems identified the relevant miRNA components, showing that the miR-19 family (including miR-19a and miR-19b) represents the most potent oncogenes in this cluster28,64,65.

Another example is miR-155 overexpression in the lymphoid compartment, which triggers B-cell leukaemia or a myeloproliferative disorder depending on the system used to drive expression of the transgene; this was the first example of an miRNA that initiates cancer in a transgenic setting66,67 (Table 1).

Gene targeting has been used extensively to delete miRNAs for the purpose of characterizing their physiological roles or action as candidate tumour suppressors. Gene targeting has suggested that miRNAs from similar families have redundant or compensatory functions, which has been shown for C. elegans68. Ablation of the miR-15a and miR-16-1 cluster, which is often deleted in human chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, predisposes mice to B-cell lymphoproliferative disease69 (Table 1). Importantly, the ability to produce mouse strains with different gene dosage through heterozygous or homozygous gene deletions has revealed that Dicer1, which if lost completely has a deleterious effect, can promote malignant phenotypes as a haploinsufficient tumour suppressor23. Such a conclusion could not be formed from studies that examined only genomic data.

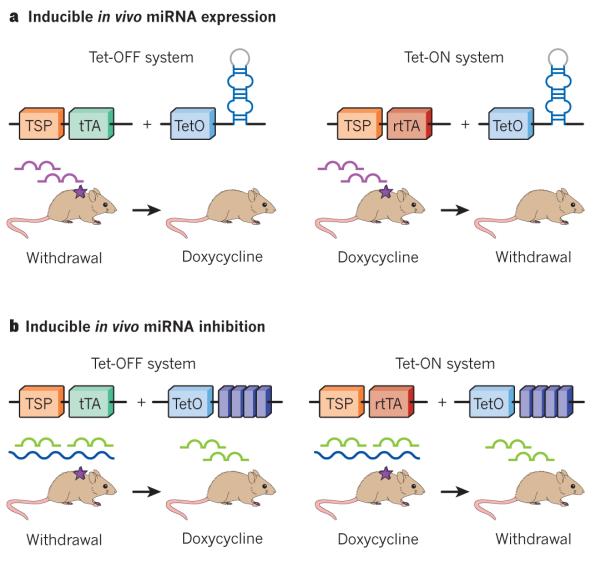

Conditional gene expression systems in mice have allowed researchers to determine cancer gene dependencies, as well as whether genes that initiate cancer also participate in tumour maintenance. In many cases, withdrawal of the initiating oncogenic transgene (or restoration of the deleted or lost tumour suppressor) leads to the collapse of the tumour; this validates the transgene or pathway that is controlled by these genes, as a therapeutic target. Similar studies have also been applied to miR-NAs; for example, conditional expression of miR-21, which is broadly deregulated in cancer, can promote lymphomagenesis in mice70 (Table 1). Silencing of miR-21 leads to disease regression, in part, by promoting apoptosis70 (Fig. 3a). Likewise, the use of miRNA inhibitors (for example, antagomirs) directed against miR-21 can inhibit the proliferation of human cancer cells that overexpress miR-21 (ref. 71). Together, these studies suggest that miR-21 antagonists have the potential to be effective therapies for at least some cancers.

Figure 3. In vivo miRNA expression or inhibition ‘á la carte’.

a, Tetracycline (Tet)-mediated miRNA inactivation or activation by doxycycline administration using Tet-OFF, in which a tissue-specific promoter (TSP) is combined with a transactivator (tTA) to turn on expression of oncogenic miRNA (purple) and induce tumorigenesis (purple star) and subsequent tumour regression, revealing dependence on the oncogenic miRNA, or Tet-ON systems in which a reverse transactivator (rtTA) switches on oncogenic miRNA when the drug is applied. Drug withdrawal leads to tumour regression. b, Tet-mediated miRNA activation or inactivation by doxycycline administration using Tet-OFF or Tet-ON systems. miRNAs (green) can be inhibited by miRNA sponges (dark blue), with the same effects as miRNA expression, leading to tumorigenesis and subsequent tumour regression, which indicates a dependence on tumour-suppressor loss.

The development of new technology has meant that mouse models are increasingly used to study gene function on a large if not genome-wide scale, and miRNAs are at the forefront of this revolution. Recently, a vast collection of mouse embryonic stem-cell clones that harbour deletions that target 392 miRNA genes was generated72. This unique and valuable toolbox, termed ‘mirKO’, will allow the creation of mice that lack specific miRNAs, express mutant miRNAs or the study of their expression. In a converse strategy, a collection of embryonic stem cells engineered to inducibly express the vast majority of known miRNAs is in production (S.W.L., Y. Park and G. Hannon, manuscript in preparation) and will allow the in vivo validation of miRNAs as oncogenes or as anticancer therapies. With a different strategy, miRNA sponges (Fig. 3b), which are oligonucleotide constructs with multiple complementary miRNA binding sites in tandem, have already been used to deplete individual miRNAs in transgenic fruitflies, in transplanted breast cancer cells in mice and in a transgenic mouse model56,73,74. Although these sponges provide a scalable strategy for miRNA loss-of-function studies, more work is needed to rule out off-target effects and assess their potency before conclusions can be made. However, the availability of such resources will help with the functional study of miRNAs in normal development and disease, and will be useful to the wider scientific community.

Finally, genetically engineered mouse models of human cancers are a testing ground for preclinical studies. For example, in Myc-induced liver tumours, miR-26 delivery by adeno-associated viruses suppresses tumorigenesis by inducing apoptosis75. The increasing use of state-of-the-art mouse models is likely to uncover new in vivo functions, such as metastasis and angiogenesis, that otherwise would have remained hidden in vitro. They will also provide key preclinical systems for testing miRNA-based therapeutics.

Constructing and deconstructing cancer

The use of RNAi technology — a tool that exploits miRNA pathways — has revolutionized the study of gene function in mammalian systems and has provided a powerful means to investigate the function of any protein-coding gene. Experimental triggers of RNAi exploit different aspects of the pathway and result in the downregulation of gene expression through incorporation into the miRNA biogenesis machinery at different points76. Small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs), which function at the level of Dicer1, can transiently and potently lead to gene suppression; these RNAi triggers, or their variants, are probably the structural ‘scaffold’ for miRNA therapeutics (see the section miRNAs as drugs or drug targets).

Stable RNAi can be activated by the expression of miRNA mimetics, that are either the so-called stem loop short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) or shRNAs that incorporate a larger miRNA fold. One example of the latter is based on miR-30 (known as miR-30-based shRNAs or ‘shRNAmirs’). These shRNAs, as occurs naturally for many miRNAs, can be embedded in non-coding sequences of protein-coding transcripts or linked in tandem, which allows, for example, the linkage of the shRNA with a fluorescent reporter or the simultaneous knockdown of two different genes77,78. Advances in the shRNAmir methodology have allowed the development of versatile vectors for the study of proliferation and survival genes, strategies for optimizing the potency of shRNAs, and rapid and effective systems for conditional shRNA expression in mice79–81. The last of these, together with systems based on short stem-loop shRNAs82, could eventually allow the spatial, temporal and reversible control of any gene in vivo.

Regardless of the platform, RNAi technology provides an effective tool to investigate cancer phenotypes and identify therapeutic targets. For example, RNAi has been used to identify and characterize tumour-suppressor genes, which if inhibited promote cancer development. Early studies, using the same system that validated miR-17-92 as an oncogene, demonstrated that inhibition of TP53 could produce phenotypes that were consistent with TP53 loss83. Later studies showed that tumour suppressors could be identified prospectively using in vitro and in vivo shRNA screens, (for examples see refs 84 and 85). By conditionally expressing shRNAs that target tumour suppressors in mice, tumour-suppressor function in advanced tumours can be re-established by silencing the shRNA86. Tumour-suppressor reactivation leads to a marked (if not complete) tumour regression, which validates these pathways as therapeutic targets.

RNAi technology can be exploited more directly to identify genotype-specific cancer drug targets. Although there may be differences in the outcome of RNAi and small-molecule-mediated protein inhibition, siRNAs and shRNAs have been widely used to determine whether a candidate target is required for the proliferation of cancer cells. Moreover, the availability of RNAi libraries that target portions of, or all, the human genome allows genetic screens to identify ‘synthetic lethal’ genes, for which, if combined, the attenuation triggers the death of the cell. In principle, the identification of an RNAi target, the inhibition of which is selectively lethal to cells harbouring a particular oncogenic alteration, should identify cancer-specific targets. Such approaches have identified potential targets for KRAS-expressing tumours87–89 and leukaemias with deregulated MYC (ref. 90). Application of these approaches could potentially be complementary to the traditional drug-target discovery approach, and possibly a systematic way to identify the combination of therapies that will ultimately be needed to combat cancer.

miRNAs as drugs and drug targets

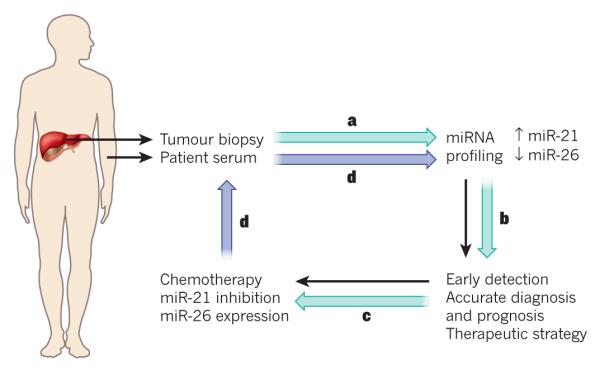

Despite advances in techniques to inhibit protein-coding genes using small molecules or biologicals, many cancers are unresponsive to the agents currently in use or become resistant to them; new and more creative approaches are therefore required for the treatment of cancer. Perhaps one of the most exciting opportunities that has arisen from our understanding of miRNA biology is the potential use of miRNA mimics or antagonists as therapeutics. Owing to the ability of miRNAs to simultaneously target multiple genes and pathways that are involved in cellular proliferation and survival38, the targeting of a single miRNA can be a form of ‘combination’ therapy that could obstruct feedback and compensatory mechanisms that would otherwise limit the effectiveness of many therapies in current use. In addition, because miRNA expression is often altered in cancer cells, agents that modulate miRNA activity could potentially produce cancer-specific effects10,91,92 . Based on this, anticancer therapies that inhibit or enhance miRNA activity are being developed (Fig. 4). Evidence for this is shown by the inhibition of oncogenic miRNAs or the expression of tumour suppressor miRNAs in mice that harbour tumours, which have a significant effect on the outcome of cancer. Oncogenic miRNAs can be blocked by using antisense oligonucleotides, antagomirs, sponges or locked nucleic acid (LNA) constructs93. The use of LNAs has achieved unexpected success in vivo, not only in mice but also for the treatment of hepatitis C in non-human primates94. The downregulation of miR-122 can lead to a significant inhibition of replication of the hepatitis C virus. This inhibition is thought to decrease the risk of chronic hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma in patients who are hepatitis C-positive. Early clinical studies using SPC3649, an miR-122 antagonist, in healthy individuals to assess toxicity will provide valuable information about pharmacokinetics and safety of the treatment. LNAs have been optimized to target miRNAs by reducing their molecular size and this, along with developing strategies for more efficient delivery, has increased their therapeutic potential95. By contrast, another strategy involves the restoration of tumour -suppressor miRNA expression by synthetic miRNA mimics or viral delivery93. Both of these approaches have yielded positive results in mouse models of cancer75,96. Adeno-associated virus delivery of miRNAs or miRNA antagonists has the advantage of being efficient and, because the virus does not integrate into the genome, non-mutagenic. However, the delivery and safety of treatment needs to be improved before this approach can achieve widespread clinical use.

Figure 4. Proposed scheme for the treatment of liver cancer with combined chemotherapy and miRNA-based therapy.

a, miRNA expression profiles of potential patients could be assessed by measuring circulating miRNAs in patient serum or tumoral miRNAs from a biopsy. For example, miR-21 expression and miR-26 loss could be detected in serum and tumour samples. b, This profile could be used for early detection of cancer, accurate diagnosis and prognosis, and choosing the best therapeutic strategy. The best available chemotherapeutic option could be combined with miRNA-based therapy. c, The oncomiRs detected in miRNA profiling and those present in the tumour, such as miR-21, could be inhibited by using different strategies, such as locked nucleic acid constructs. By contrast, the expression of tumour-suppressor miRNAs downregulated in the tumour could be restored and miR-26 levels could be increased with miRNA mimics. d, After treatment, the patient could be checked for relapse by periodically studying circulating miRNAs from serum in a non-invasive manner. The presence of miR-21 could indicate a potential relapse, and treatment would resume (black arrows).

In principle, the use of miRNA mimetics as therapeutics would allow ‘drugging the undruggable’ or the therapeutic inhibition of virtually any human gene. If this were possible it would undoubtedly impact many diseases including cancer by allowing the targeting of oncogenic transcription factors that are difficult to inhibit through traditional medicinal chemistry97. Furthermore, owing to the similar chemistry that is used to create drugs that target diverse molecules, the implementation of miRNA-based therapies could allow a more uniform drug development pipeline than is possible for more conventional treatments. Although experimental studies have validated the underlying biological impact of achieving miRNA modulation, there are still practical challenges that prevent the use of miRNA mimetics and antagonists clinically, including uncharacterized off-target effects, toxicities and poor agent-delivery. Concerning the last of these, most miRNA mimetics and antagonists rely on the delivery of molecules that mimic or inhibit the ‘seed’ sequence of an miRNA (typically molecules that consist of ≥6 nucleotides or related structures) across the plasma membrane — a particular challenge in the treatment of cancer, in which missing even a few cancer cells could lead to tumour relapse and progression. Extensive research is now focused on the viral and non-viral strategies required to meet this challenge, and results in the preclinical setting are promising75,94–96. Despite the considerable hurdles that have to be overcome, it seems likely that miRNAs will find a place alongside more conventional approaches for the treatment of cancer.

Perspectives

Since the discovery of miRNAs in model organisms, miRNAs have emerged as key regulators of normal development and a diversity of normal cellular processes. Given what we know now, it is not surprising that perturbations in miRNA biogenesis or expression can contribute to disease. In cancer, the effects of miRNA alteration can be widespread and profound, and they touch on virtually all aspects of the malignant phenotype. Yet, precisely how miRNAs regulate the expression of protein-coding genes is not completely understood, and the underlying mechanism remains an important basic-science question that will have a significant impact on our understanding of gene regulation and its alteration in disease. In addition, we still lack effective approaches to understand and predict miRNA targets. New strategies to identify and characterize the targets of individual miRNAs, and to determine how they function in combination to regulate specific targets, will be required to understand their action on cell physiology. Because miRNAs can also regulate other non-coding RNAs (for example, long non-coding RNAs), which have a role in cancer development and vice versa98, these interactions will increase the complexity of gene regulation and are likely to produce regulatory processes that are currently hidden. Pioneering knowledge, gained through the study of miRNA function and regulation, will undoubtedly provide methodological and theoretical insights that will help in our understanding of the more recently identified non-coding RNA species.

Understanding miRNA biology and how it contributes to cancer development is not only an academic exercise, but also provides an opportunity for the generation of new ideas for diagnosis and treatment. RNAi-based technology has allowed sophisticated loss-of-function experiments that were previously impossible and has revealed therapeutic targets that, when inhibited, can lead to cancer cell elimination. In addition, miRNAs themselves are being used directly in the diagnosis of cancer and, in the future, will probably be exploited in therapy to identify drug targets or as the drug treatment. However, cost-effective miRNA profiling strategies and larger studies are needed to determine whether miRNA profiling provides an advantage for cancer classification compared with a more traditional approach. Although drugs that function as miRNA mimetics, antagonists or synthetic siRNAs form the core of what is fundamentally a new class of drugs that are capable of targeting molecules outside the range of traditional medicinal chemistry, their clinical implementation will require improvements in drug composition and delivery; these challenges lie outside the scope of molecular biology and instead involve the fields of chemistry and nanotechnology. Nevertheless, the successful development of these technologies could ultimately translate our understanding of miRNA biology in cancer into strategies for the control of cancer.

Acknowledgements

We apologize to all colleagues whose work could not be cited owing to space restrictions. We thank L. Dow, A. Ventura, A. Saborowski and V. Aranda for their comments on the manuscript, and G. Hannon and L. He for the many discussions. A.L. is supported by an EMBO Long-Term Fellowship. S.W.L. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

Footnotes

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of this article at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. Post-transcriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;75:855–862. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calin GA, et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro-RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. This article reports miRNA deregulation in cancer and is the first evidence of the role of miRNAs in cancer.

- 6.Lu J, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. This article systematically profiles miRNAs in cancer and demonstrates their potential as classifiers.

- 7.O’Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Zeller KI, Dang CV, Mendell JT. c-Myc-regulated microRNAs modulate E2F1 expression. Nature. 2005;435:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nature03677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He L, et al. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature. 2005;435:828–833. doi: 10.1038/nature03552. References 7 and 8 show, for the first time, that miRNAs can be actively involved in the MYC signalling pathway.

- 9.Calin GA, et al. Human microRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and genomic regions involved in cancers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:2999–3004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307323101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saito Y, et al. Specific activation of microRNA-127 with downregulation of the proto-oncogene BCL6 by chromatin-modifying drugs in human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayr C, Hemann MT, Bartel DP. Disrupting the pairing between let-7 and Hmga2 enhances oncogenic transformation. Science. 2007;315:1576–1579. doi: 10.1126/science.1137999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veronese A, et al. Mutated β-catenin evades a microRNA-dependent regulatory loop. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:4840–4845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101734108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diederichs S, Haber DA. Sequence variations of microRNAs in human cancer: alterations in predicted secondary structure do not affect processing. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6097–6104. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuchenbauer F, et al. In-depth characterization of the microRNA transcriptome in a leukemia progression model. Genome Res. 2008;18:1787–1797. doi: 10.1101/gr.077578.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanaihara N, et al. Unique microRNA molecular profiles in lung cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calin GA, et al. A microRNA signature associated with prognosis and progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:1793–1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenfeld N, et al. MicroRNAs accurately identify cancer tissue origin. Nature Biotechnol. 2008;26:462–469. doi: 10.1038/nbt1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xi Y, et al. Systematic analysis of microRNA expression of RNA extracted from fresh frozen and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples. RNA. 2007;13:1668–1674. doi: 10.1261/rna.642907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell PS, et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:10513–10518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang TC, et al. Widespread microRNA repression by Myc contributes to tumorigenesis. Nature Genet. 2008;40:43–50. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomson JM, et al. Extensive post-transcriptional regulation of microRNAs and its implications for cancer. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2202–2207. doi: 10.1101/gad.1444406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar MS, Lu J, Mercer KL, Golub TR, Jacks T. Impaired microRNA processing enhances cellular transformation and tumorigenesis. Nature Genet. 2007;39:673–677. doi: 10.1038/ng2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar MS, et al. Dicer1 functions as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2700–2704. doi: 10.1101/gad.1848209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merritt WM, et al. Dicer, Drosha, and outcomes in patients with ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:2641–2650. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melo SA, et al. A TARBP2 mutation in human cancer impairs microRNA processing and DICER1 function. Nature Genet. 2009;41:365–370. doi: 10.1038/ng.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 26.Melo SA, et al. A genetic defect in exportin-5 traps precursor microRNAs in the nucleus of cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:303–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newman MA, Hammond SM. Emerging paradigms of regulated microRNA processing. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1086–1092. doi: 10.1101/gad.1919710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mavrakis KJ, et al. Genome-wide RNA-mediated interference screen identifies miR-19 targets in Notch-induced T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature Cell Biol. 2010;12:372–379. doi: 10.1038/ncb2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portela A, Esteller M. Epigenetic modifications and human disease. Nature Biotechnol. 2010;28:1057–1068. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao Q, et al. Coordinated regulation of Polycomb Group complexes through microRNAs in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fabbri M, et al. MicroRNA-29 family reverts aberrant methylation in lung cancer by targeting DNA methyltransferases 3A and 3B. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:15805–15810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707628104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varambally S, et al. Genomic loss of microRNA-101 leads to overexpression of histone methyltransferase EZH2 in cancer. Science. 2008;322:1695–1699. doi: 10.1126/science.1165395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang HW, Wentzel EA, Mendell JT. A hexanucleotide element directs microRNA nuclear import. Science. 2007;315:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1136235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khraiwesh B, et al. Transcriptional control of gene expression by microRNAs. Cell. 2010;140:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gebeshuber CA, Zatloukal K, Martinez J. miR-29a suppresses tristetraprolin, which is a regulator of epithelial polarity and metastasis. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:400–405. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Small EM, Olson EN. Pervasive roles of microRNAs in cardiovascular biology. Nature. 2011;469:336–342. doi: 10.1038/nature09783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bueno MJ, et al. Combinatorial effects of microRNAs to suppress the Myc oncogenic pathway. Blood. 2011;117:6255–6266. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-315432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bui TV, Mendell JT. Myc: maestro of microRNAs. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:568–575. doi: 10.1177/1947601910377491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dews M, et al. Augmentation of tumor angiogenesis by a Myc-activated microRNA cluster. Nature Genet. 2006;38:1060–1065. doi: 10.1038/ng1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cairo S, et al. Stem cell-like micro-RNA signature driven by Myc in aggressive liver cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:20471–20476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009009107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kent OA, et al. Repression of the miR-143/145 cluster by oncogenic Ras initiates a tumor-promoting feed-forward pathway. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2754–2759. doi: 10.1101/gad.1950610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson SM, et al. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. This article reports the first evidence of an oncogene, KRAS, being targeted by an miRNA.

- 43.He L, He X, Lowe SW, Hannon GJ. microRNAs join the p53 network– another piece in the tumour-suppression puzzle. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:819–822. doi: 10.1038/nrc2232. This comprehensive review describes the regulation of the miR-34 family by the tumour suppressor p53.

- 44.Pichiorri F, et al. Downregulation of p53-inducible microRNAs 192, 194, and 215 impairs the p53/MDM2 autoregulatory loop in multiple myeloma development. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:367–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 45.Xiao J, Lin H, Luo X, Wang Z. miR-605 joins p53 network to form a p53:miR-605:Mdm2 positive feedback loop in response to stress. EMBO J. 2011;30:524–532. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamakuchi M, et al. P53-induced microRNA-107 inhibits HIF-1 and tumor angiogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:6334–6339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911082107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang CJ, et al. p53 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stem cell properties through modulating miRNAs. Nature Cell Biol. 2011;13:317–323. doi: 10.1038/ncb2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim T, et al. p53 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition through microRNAs targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:875–883. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swarbrick A, et al. miR-380-5p represses p53 to control cellular survival and is associated with poor outcome in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. Nature Med. 2010;16:1134–1140. doi: 10.1038/nm.2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu W, et al. Negative regulation of tumor suppressor p53 by microRNA miR-504. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:689–699. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzuki HI, et al. Modulation of microRNA processing by p53. Nature. 2009;460:529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature08199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Su X, et al. TAp63 suppresses metastasis through coordinate regulation of Dicer and miRNAs. Nature. 2010;467:986–990. doi: 10.1038/nature09459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ma L, Teruya-Feldstein J, Weinberg RA. Tumour invasion and metastasis initiated by microRNA-10b in breast cancer. Nature. 2007;449:682–688. doi: 10.1038/nature06174. This study demonstrates for the first time that miRNAs are involved in tumour invasion and metastasis.

- 54.Tavazoie SF, et al. Endogenous human microRNAs that suppress breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2008;451:147–152. doi: 10.1038/nature06487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ma L, et al. miR-9, a MYC/MYCN-activated microRNA, regulates E-cadherin and cancer metastasis. Nature Cell Biol. 2010;12:247–256. doi: 10.1038/ncb2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valastyan S, et al. A pleiotropically acting microRNA, miR-31, inhibits breast cancer metastasis. Cell. 2009;137:1032–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 57.Cano A, Nieto MA. Non-coding RNAs take centre stage in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:357–359. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Korpal M, et al. Direct targeting of Sec23a by miR-200s influences cancer cell secretome and promotes metastatic colonization. Nature Med. 2011;17:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nm.2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martello G, et al. A microRNA targeting Dicer for metastasis control. Cell. 2010;141:1195–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Godlewski J, et al. MicroRNA-451 regulates LKB1/AMPK signaling and allows adaptation to metabolic stress in glioma cells. Mol. Cell. 2010;37:620–632. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gao P, et al. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:762–765. doi: 10.1038/nature07823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anand S, et al. MicroRNA-132-mediated loss of p120RasGAP activates the endothelium to facilitate pathological angiogenesis. Nature Med. 2010;16:909–914. doi: 10.1038/nm.2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mu P, et al. Genetic dissection of the miR-17~92 cluster of microRNAs in Myc-induced B-cell lymphomas. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2806–2811. doi: 10.1101/gad.1872909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olive V, et al. miR-19 is a key oncogenic component of mir-17-92. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2839–2849. doi: 10.1101/gad.1861409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Costinean S, et al. Pre-B cell proliferation and lymphoblastic leukemia/high-grade lymphoma in E(mu)-miR155 transgenic mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:7024–7029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602266103. This article reports overexpression of a single miRNA can cause cancer in vivo.

- 67.O’Connell RM, et al. Sustained expression of microRNA-155 in hematopoietic stem cells causes a myeloproliferative disorder. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:585–594. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miska EA, et al. Most Caenorhabditis elegans microRNAs are individually not essential for development or viability. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Klein U, et al. The DLEU2/miR-15a/16-1 cluster controls B cell proliferation and its deletion leads to chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Medina PP, Nolde M, Slack FJ. OncomiR addiction in an in vivo model of microRNA-21-induced pre-B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2010;467:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature09284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chan JA, Krichevsky AM, Kosik KS. MicroRNA-21 is an antiapoptotic factor in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6029–6033. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prosser HM, Koike-Yusa H, Cooper JD, Law FC, Bradley A. A resource of vectors and ES cells for targeted deletion of microRNAs in mice. Nature Biotechnol. 2011;29:840–845. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Loya CM, Lu CS, Van Vactor D, Fulga TA. Transgenic microRNA inhibition with spatiotemporal specificity in intact organisms. Nature Methods. 2009;6:897–903. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhu Q, et al. A sponge transgenic mouse model reveals important roles for the miRNA-183/96/182 cluster in post-mitotic photoreceptors of the retina. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;2865:31749–31760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.259028. This article reports the development of the first sponge transgenic mouse that allows in vivo inhibition of one or several miRNAs.

- 75.Kota J, et al. Therapeutic microRNA delivery suppresses tumorigenesis in a murine liver cancer model. Cell. 2009;137:1005–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.021. This article uses adenovirus-associated vectors to deliver miRNAs to the liver and treat cancer.

- 76.Czech B, Hannon GJ. Small RNA sorting: matchmaking for Argonautes. Nature Rev. Genet. 2011;12:19–31. doi: 10.1038/nrg2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chicas A, et al. Dissecting the unique role of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor during cellular senescence. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:376–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stegmeier F, Hu G, Rickles RJ, Hannon GJ, Elledge SJ. A lentiviral microRNA-based system for single-copy polymerase II-regulated RNA interference in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:13212–13217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506306102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zuber J, et al. Toolkit for evaluating genes required for proliferation and survival using tetracycline-regulated RNAi. Nature Biotechnol. 2010;29:79–83. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fellmann C, et al. Functional identification of optimized RNAi triggers using a massively parallel sensor assay. Mol. Cell. 2011;41:733–746. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Premsrirut PK, et al. A rapid and scalable system for studying gene function in mice using conditional RNA interference. Cell. 2011;145:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Seibler J, et al. Reversible gene knockdown in mice using a tight, inducible shRNA expression system. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2007;35:e54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hemann MT, et al. An epi-allelic series of p53 hypomorphs created by stable RNAi produces distinct tumor phenotypes in vivo. Nature Genet. 2003;33:396–400. doi: 10.1038/ng1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zender L, et al. An oncogenomics-based in vivo RNAi screen identifies tumor suppressors in liver cancer. Cell. 2008;135:852–864. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Westbrook TF, et al. A genetic screen for candidate tumor suppressors identifies REST. Cell. 2005;121:837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xue W, et al. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature. 2007;445:656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature05529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Luo J, et al. A genome-wide RNAi screen identifies multiple synthetic lethal interactions with the Ras oncogene. Cell. 2009;137:835–848. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Scholl C, et al. Synthetic lethal interaction between oncogenic KRAS dependency and STK33 suppression in human cancer cells. Cell. 2009;137:821–834. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Barbie DA, et al. Systematic RNA interference reveals that oncogenic KRAS-driven cancers require TBK1. Nature. 2009;462:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature08460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zuber J, et al. RNAi screen identifies Brd4 as a therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2011;478:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature10334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gumireddy K, et al. Small-molecule inhibitors of microRNA miR-21 function. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2008;47:7482–7484. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Melo S, et al. Small molecule enoxacin is a cancer-specific growth inhibitor that acts by enhancing TAR RNA-binding protein 2-mediated microRNA processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:4394–4399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014720108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Garzon R, Marcucci G, Croce CM. Targeting microRNAs in cancer: rationale, strategies and challenges. Nature Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:775–789. doi: 10.1038/nrd3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lanford RE, et al. Therapeutic silencing of microRNA-122 in primates with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Science. 2009;327:198–201. doi: 10.1126/science.1178178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Obad S, et al. Silencing of microRNA families by seed-targeting tiny LNAs. Nature Genet. 2011;43:371–378. doi: 10.1038/ng.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bonci D, et al. The miR-15a-miR-16-1 cluster controls prostate cancer by targeting multiple oncogenic activities. Nature Med. 2008;14:1271–1277. doi: 10.1038/nm.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kumar MS, et al. Suppression of non-small cell lung tumor development by the let-7 microRNA family. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3903–3908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712321105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Poliseno L, et al. A coding-independent function of gene and pseudogene mRNAs regulates tumour biology. Nature. 2010;465:1033–1038. doi: 10.1038/nature09144. This elegant study shows how mRNA from genes and pseudogenes can compete for the binding of miRNAs, unveiling the complexity of miRNA regulatory networks.

- 99.Ruby JG, Jan CH, Bartel DP. Intronic microRNA precursors that bypass Drosha processing. Nature. 2007;448:83–86. doi: 10.1038/nature05983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cheloufi S, Dos Santos CO, Chong MM, Hannon GJ. A dicer-independent miRNA biogenesis pathway that requires Ago catalysis. Nature. 2010;465:584–589. doi: 10.1038/nature09092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]