Figure 6.

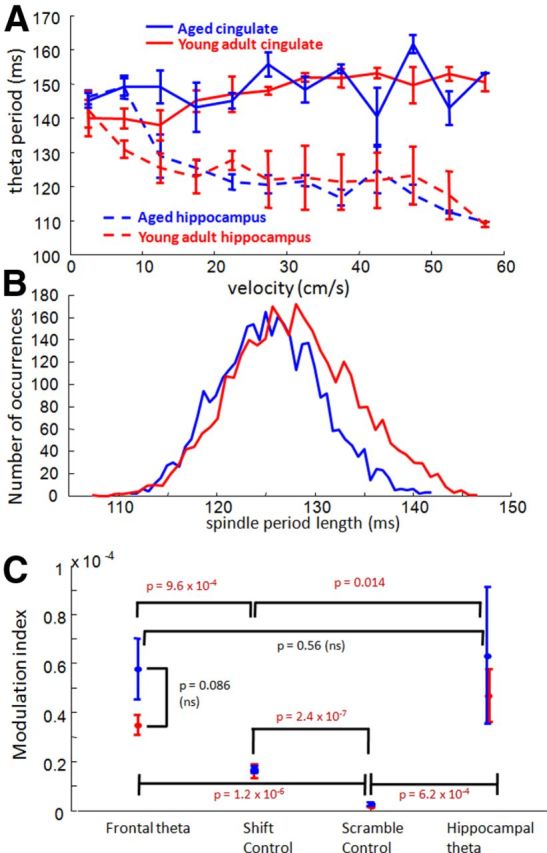

Age comparison of other oscillations: theta, spindles, and theta–gamma coupling. A, The period length of the 6–10 Hz theta oscillation recorded from the cingulate cortex (solid lines) and recorded from electrodes in the dorsal hippocampus (dashed lines), across running speeds. In the hippocampus, theta period length was modulated by the rat's running speed, but there was no overall difference between period length in younger compared with older rats (red and blue traces, respectively; 2-way ANOVA, speed, F(11,88) = 5.76, p = 0; age, F(1,88) = 0.37, p = 0.55; interaction, F(11,88) = 0.99, p = 0.46). Theta frequency in the anterior cingulate cortex also did not differ between age groups (paired t test, p = 0.6). B, A histogram of the spindle period lengths in young (red) and aged (blue) rats. The width of spindles was not significantly different between age groups (p = 0.5). C, The relationship between theta phase and instantaneous gamma amplitude (modulation index, y-axis) was averaged across rats within age groups (left) and compared against modulation indices using shifted theta phases, scrambled theta phases, or theta phases from hippocampal electrodes (x-axis; for more details, see Materials and Methods). Although coupling between theta phase and gamma power was significant (i.e., the modulation indices exceeded shift and scramble control modulation indices), there were no significant age differences in either frontal–frontal or hippocampal–frontal theta–gamma coupling. Differences that did exist between individual rats appeared to depend on the strength (amplitude) of the measured gamma signal (data not shown).