Abstract

Steroid hormones act, through their respective nuclear receptors, to regulate target gene expression. Despite their critical role in development, physiology, and disease, however, it is still unclear how these systemic cues are refined into tissue-specific responses. We identified a mutation in the evolutionarily conserved DEAD box RNA helicase belle/DDX3 that disrupts a subset of responses to the steroid hormone ecdysone during Drosophila melanogaster metamorphosis. We demonstrate that belle directly regulates translation of E74A, an ets transcription factor and critical component of the ecdysone-induced transcriptional cascade. Although E74A mRNA accumulates to abnormally high levels in belle mutant tissues, no E74A protein is detectable, resulting in misregulation of E74A-dependent ecdysone response genes. The accumulation of E74A mRNA in belle mutant salivary glands is a result of auto-regulation, fulfilling a prediction made by Ashburner nearly 40 years ago. In this model, Ashburner postulates that, in addition to regulating secondary response genes, protein products of primary response genes like E74A also inhibit their own ecdysone-induced transcription. Moreover, although ecdysone-triggered transcription of E74A appears to be ubiquitous during metamorphosis, belle-dependent translation of E74A mRNA is spatially restricted. These results demonstrate that translational control plays a critical, and previously unknown, role in refining transcriptional responses to the steroid hormone ecdysone.

Author Summary

Pulses of steroid hormones regulate a variety of biological processes, but how these simple global cues are converted into specific local responses remains unclear. While steroid responses have traditionally been thought to be regulated at the transcriptional level, here we demonstrate that translational control plays a novel role in refining steroid signals. The DEAD box RNA helicase belle directly regulates the translation of E74A mRNA, which encodes a transcription factor that is induced by the fly steroid hormone ecdysone and then rapidly repressed. This process is disrupted in belle mutant tissues, where E74A mRNA accumulates to abnormally high levels but is not translated. We demonstrate that Belle-dependent translation of E74A is required to both repress its own transcription and to induce tissue-specific target genes. These findings confirm the prediction that auto-regulation is important for the self-limiting behavior of steroid responses and demonstrate a critical role for translational control in refining a global hormonal signal into specific biological responses.

Introduction

Steroid hormones regulate a wide variety of biological responses during development and physiological homeostasis. These small lipophilic compounds act, through their respective nuclear receptors, to directly regulate target gene transcription. This initial transcriptional response occurs within minutes and does not require new protein synthesis; within hours of hormone exposure, however, expression of a larger set of genes is initiated, this response does require new protein synthesis. This hierarchical model of steroid-induced transcriptional responses was originally proposed to explain the sequential appearance of polytene chromosome puffs in insect larval salivary glands in response to the steroid hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone (hereafter referred to as ecdysone) [1]. Thus, steroid-triggered transcriptional targets have been historically divided into two groups based on their sequence of expression and their dependence on new protein synthesis: “early” or primary response genes and, “late” or secondary response genes. Many primary response genes encode transcription factors that regulate transcription of secondary response genes, which, in turn, encode critical regulators that direct biological responses [2]. However, it remains poorly understood how systemic steroid hormone pulses are refined into distinct transcriptional cascades that direct tissue-specific responses.

Pulses of ecdysone trigger the major developmental transitions during Drosophila development. At the onset of metamorphosis, two sequential pulses transform a crawling larva into an immature adult within half a day. The first pulse, at the end of larval development, triggers puparium formation and initiates prepupal development. Approximately 12 hours later, the prepupal pulse triggers head eversion and initiates pupal development. This transformation from larva to pupa requires the rapid and parallel execution of two major types of processes: the morphogenesis of small clusters of precursor cells into adult structures and the destruction of obsolete larval tissues. Ecdysone triggers both of these processes in a stage- and tissue-specific manner. Thus, these events at the onset of metamorphosis provide an ideal context within which to study the mechanisms that mediate specificity to systemic pulses of ecdysone.

Our approach is to use unbiased genetic screens to identify mutations that disrupt a subset of tissue-specific responses to ecdysone at the onset of metamorphosis, expecting that these mutations, and the genes they affect, will provide insights into mechanisms that mediate specificity to hormonal pulses. Our primary experimental context is the destruction of larval salivary glands in response to the prepupal pulse of ecdysone. Reverse genetic approaches have led to the identification of three ecdysone early response genes required for this ecdysone-triggered biological response. Loss of E74A (FBgn0000567), E93 (FBgn0264490) or BR-C (FBgn0000210) disrupt the ecdysone-induced expression of apoptotic activators reaper (rpr) (FBgn0011706) and head involution defective (hid) (FBgn0003997) and result in a persistent salivary gland (PSG) phenotype [3]–[6]. We previously completed a large-scale EMS mutagenesis to identify additional mutations that specifically disrupt this ecdysone-triggered response [7]. Here, we report our analysis of one of these newly identified PSG mutations that maps to the DEAD box RNA helicase belle (FBgn0263231).

DEAD box RNA helicases are characterized by the presence of an Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp (DEAD) motif and use ATP to bind or remodel RNA and RNA-protein complexes (ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes) [8]. Members of this family of proteins contain a highly conserved helicase core with many characteristic sequence motifs that include binding sites for ATP and RNA. The helicase core is flanked by domains that are thought to allow interactions with other proteins or with the target RNA. belle and its orthologs from yeast (Ded1) (YOR204W) to humans (DDX3) (ENSG00000215301) are thought to be involved in many aspects of RNA metabolism, including pre-mRNA splicing, nuclear RNA export, RNA interference, translational repression and translational initiation. Recent work with the yeast ortholog Ded1 provides a model for how this family of proteins regulate both translation initiation and repression [9]. Ded1 directly assembles a translational pre-initiation complex which represses translation; after subsequent ATP-hydrolysis, Ded1 releases the RNP complex allowing translation initiation. However, the role of belle/DDX3 in development remains poorly understood.

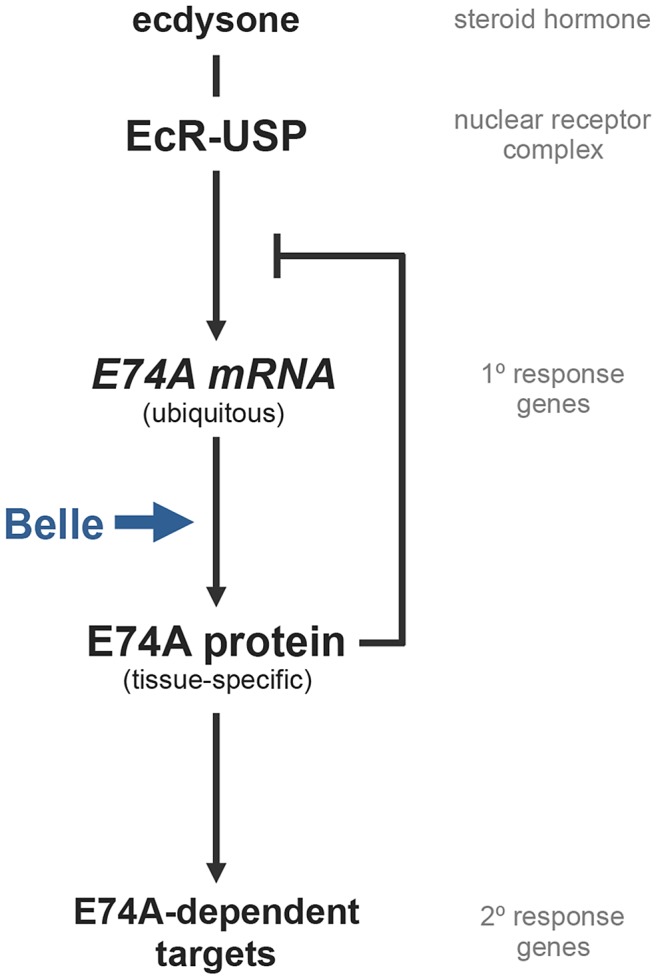

We demonstrate that belle-dependent translational control regulates a subset of transcriptional cascades triggered by ecdysone during Drosophila metamorphosis. We identify the ecdysone early response gene E74A as a critical mRNA target of Belle. Thus, belle-dependent translation of E74A determines whether E74A-dependent targets of the ecdysone transcriptional cascade are properly regulated. One property of this translational control is that E74A protein is expressed in a subset of cells and tissues during metamorphosis even though ecdysone-triggered transcription of E74A occurs in most, if not all, cells. Our results also provide insight into mechanisms that mediate the self-limiting behavior of steroid-triggered transcriptional responses.

Results

belle disrupts a subset of ecdysone-triggered responses during metamorphosis

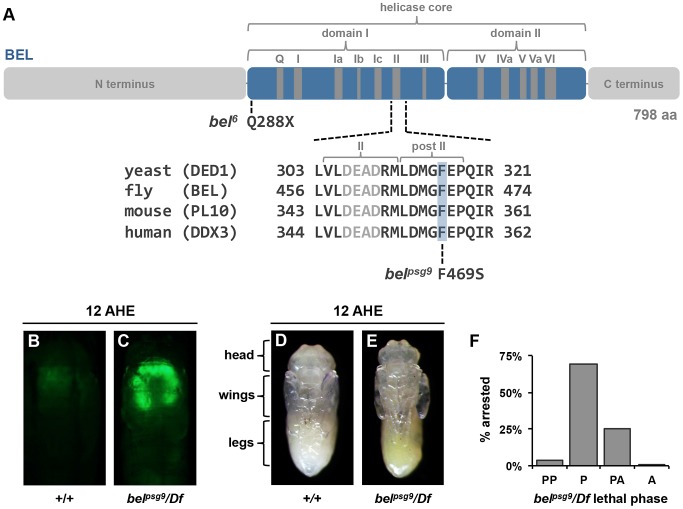

To obtain insights into the mechanisms that regulate specificity to systemic pulses of ecdysone, we previously conducted a genetic screen for mutations that disrupt the ecdysone-triggered destruction of larval salivary glands during metamorphosis [7]. Here, we report characterization of one mutation identified in this screen: psg9. We used recombination mapping with pairs of dominant markers to estimate the location of the psg9 locus (method described in [7]) and performed complementation tests with chromosomal deficiencies to further refine its location. This approach placed psg9 in a molecularly defined region that contained seven candidate genes, including the DEAD box RNA helicase belle (Figure S1A). Subsequent complementation tests with available lethal mutations in this region, Sanger sequencing and RNA-interference knockdown of candidate genes, confirmed that the EMS-induced lesion in psg9 mapped to belle (data not shown). psg9 failed to complement previously reported lethal mutations in belle, including the EMS-induced allele bel6 [10]–[12] and the P-element-induced allele belL4740 [13] (Figure S1B). Sequencing the belle open reading frame in psg9 mutant animals identified a single missense mutation that results in a non-polar to polar substitution (F469S) within a region that is identical among belle's orthologs from yeast to humans (Figure 1A; see “II” and “post II”). Previously reported mutations in either the DEAD box-containing motif II or the belle/DDX3 family-specific post II region disrupt translation of target mRNAs [9], [14]. Thus, belpsg9 likely disrupts translational initiation of belle targets during Drosophila development.

Figure 1. Mutation in belle disrupts a subset of ecdysone-triggered responses during metamorphosis.

(A) Schematic of conserved motifs in the DEAD-box RNA helicase (adapted from [8]) and sequence alignment of the DEAD-box containing motif II and the belle/DDX3 family-specific post II region. belpsg9 has a missense mutation that changes a phenylalanine to a serine at residue 469 within the post II region. bel6 has a nonsense mutation at residue 288 introducing an early stop codon. (B–C) Live pupae at 12 AHE with salivary gland specific expression of GFP. Salivary gland GFP (fkh-GAL4, UAS-GFP) is no longer present in control animals at 12 AHE (B) but persists in similarly staged belpsg9 mutant glands (C), indicating a block in the ecdysone-triggered destruction of this tissue. (D–E) Control (D) and belpsg9 mutant (E) pupae dissected out of their pupal cases 12 hours after head eversion (AHE). Both control and mutant pupae have everted heads and fully extended legs and wings, suggesting that the global ecdysone-induced genetic hierarchy is intact. (F) Lethal phase analysis of belpsg9 hemizygous animals. Most (70%) belpsg9 mutant animals arrest as newly formed pupae (n = 215). PP: prepupae, P: pupae, PA: pharate adults, A: adults eclosed.

belpsg9 mutant (refers to belpsg9/Df unless otherwise stated) animals showed a strong persistent salivary gland (PSG) phenotype (93%, n = 94) (Figure 1C and Figure S1B), indicating a block in the ecdysone-triggered destruction of this larval tissue. This defect was not due to a general inability to respond to ecdysone. Prior salivary gland-specific responses to ecdysone, like synthesis of glue proteins during the mid-third instar and secretion of gland contents during puparium formation, occur normally in belpsg9 mutant salivary glands (data not shown). In addition, belpsg9 mutant animals pupariate, head evert and extend their legs normally (Figure 1E), indicating that the global ecdysone-induced genetic hierarchy was not affected. Most belpsg9 mutant animals arrest progression of development soon after head eversion as newly formed pupae (Figure 1F). This stage-specific lethal phase during metamorphosis is unique to the belpsg9 allele. Two previously described mutations, bel6 and belL4740, have lethal phases early in development without any mutant animals surviving to metamorphosis (Figure S1B). Both alleles are likely strong hypomorphic or null alleles: belL4740 does not appear to make any protein [13] and we identified a nonsense mutation in bel6 (Q288X) that removes the entire RNA helicase and C-terminal domains (Figure 1A). Accordingly, belpsg9 transheterozygous (belpsg9/bel6 and belpsg9/belL4740) animals have a similar phenotype to belpsg9 hemizygous animals, arresting after head eversion with a highly penetrant block in the destruction of larval salivary glands (Figure S1B). Thus, belpsg9 disrupts a subset of ecdysone-regulated responses and is required for progression through metamorphosis.

Ecdysone early-response genes are properly induced

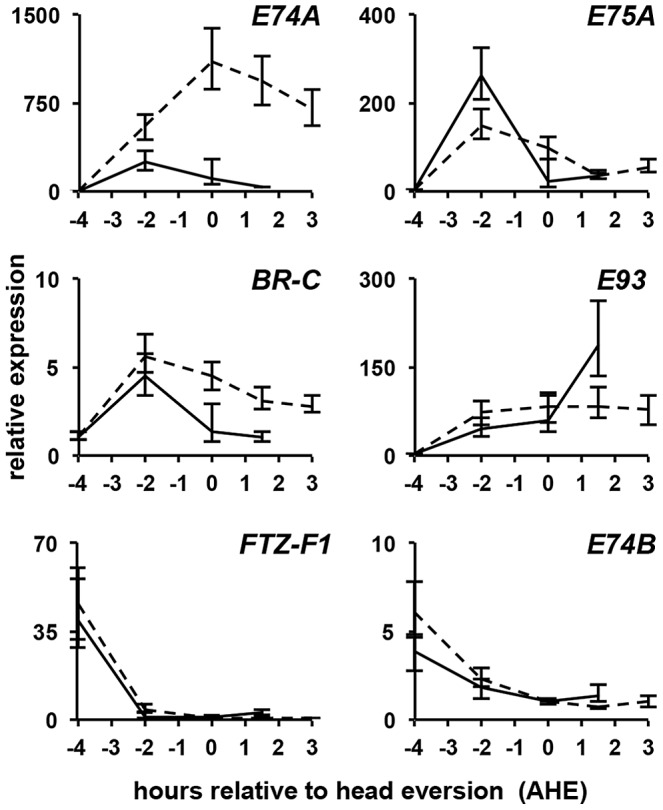

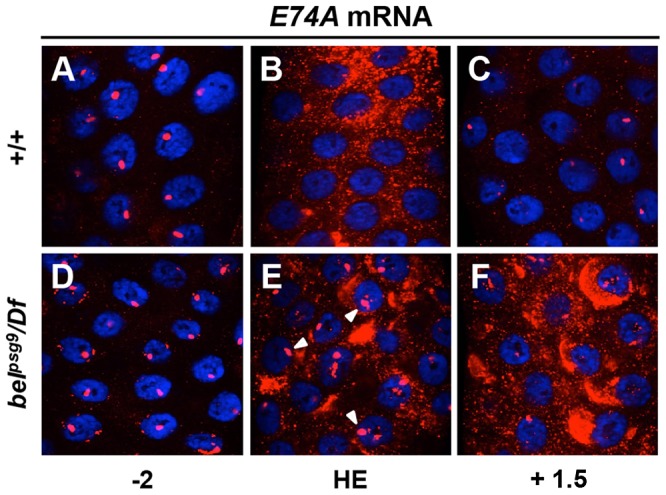

Given the highly penetrant PSG phenotype in belpsg9 mutant animals, we used the ecdysone-triggered destruction of larval salivary glands as an experimental context for molecular characterization of belle function. As a first step towards understanding how belpsg9 disrupts this ecdysone-triggered response, we examined expression of key components of the ecdysone-induced transcriptional hierarchy. Salivary glands were dissected from control and mutant animals staged relative to head eversion (hours after head eversion or AHE) and subjected to quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (qPCR) analysis. As expected, in control salivary glands, expression of the classical ecdysone early response genes E74A, E75A (FBgn0000568) and BR-C, and the stage-specific ecdysone early response gene E93, peak with the prepupal pulse of ecdysone at −2 AHE (Figure 2, solid lines). In belpsg9 mutant salivary glands, these ecdysone early response genes are similarly induced by −2 AHE (Figure 2, dashed lines). Accordingly, RNA in situ hybridizations with probes directed to E74A mRNA indicate that ecdysone-induced transcription of early response genes was not affected. In both control and belpsg9 mutant glands at −2 AHE, E74A RNA staining appears as single bands inside the nucleus, reflecting staining of newly transcribed RNA within ecdysone-induced puffs on polytene chromosomes (Figure 3A and 3D). Thus, transcription triggered by the prepupal pulse of ecdysone was unaffected in belpsg9 mutant salivary glands.

Figure 2. belle selectively disrupts regulation of the ecdysone early response gene E74A.

qPCR analysis of ecdysone hierarchy genes in control (solid lines) and belpsg9 mutant (dashed lines) larval salivary glands. Expression profiles of the ecdysone hierarchy genes E75A, BR-C, E93, FTZ-F1 and E74B are relatively normal in belpsg9 mutant salivary glands. In contrast, the early response gene E74A is not properly repressed. y-axis plots relative expression, normalized to rp49; x-axis plots developmental stage relative to head eversion. Each time point represents three independently isolated salivary gland samples. AHE: after head eversion.

Figure 3. Transcription of E74A is not properly repressed in belle salivary glands.

Fluorescent in situ hybridizations for E74A mRNA in control (A–C) and belpsg9 mutant (D–F) salivary glands shown in red with DAPI costained nuclei in blue. Two hours before head eversion (−2 AHE), E74A mRNA is detected as strong nuclear bands indicative of active transcription at ecdysone-induced chromosomal puffs in both control (A) and mutant (D) glands. In control glands at head eversion (HE) (B), E74A mRNA is primarily cytoplasmic and nuclear puff staining is no longer detectable. In contrast, belpsg9 mutant glands at HE (E) show continued nuclear puff staining (arrowheads) and increased cytoplasmic staining. At +1.5 AHE, E74A mRNA is barely detectable in control glands (C). Similarly staged mutant glands (F) show continued accumulation of cytoplasmic E74A RNA. HE: head eversion.

Ecdysone-induced transcription of E74A is not properly repressed

A hallmark of the classical ecdysone early response genes E74A, E75A and BR-C is that their expression increases with rising titers of ecdysone but quickly regresses to basal levels. This self-limiting behavior is evident in salivary glands dissected from control animals, where E74A, E75A and BR-C mRNA return to low levels two hours after their peak expression (Figure 2). In belpsg9 mutant salivary glands, however, E74A mRNA expression continues to rise, reaching ∼1,000-fold induction by head eversion and failing to return to pre-pulse levels even three hours later (Figure 2). Salivary gland-specific knockdown of belle using RNA interference shows a similar effect on E74A mRNA levels (data not shown), suggesting that the effects of belle are cell autonomous. The ecdysone-dependent repression of mid-prepupal genes ftz-f1 (FBgn0001078) and E74B occurs normally in belpsg9 mutant glands (Figure 2), suggesting that the ecdysone regulated transcriptional repression machinery is unaffected. We then used RNA in situ hybridizations to further characterize the E74A mRNA defects in belpsg9 mutant salivary glands. In control glands, the ecdysone-induced nuclear puff staining at −2 AHE (Figure 3A), disappears by head eversion when E74A RNA is predominantly cytoplasmic (Figure 3B). In belpsg9 mutant glands at head eversion, however, E74A RNA is still detected in strong nuclear puffs (Figure 3E; see arrowheads), suggesting that transcription of E74A and the associated polytene chromosome puffs fail to regress. These mutant glands show increased accumulation of cytoplasmic E74A RNA (Figure 3E), a likely consequence of continued transcription. By +1.5 AHE, belpsg9 mutant salivary glands show further accumulation of cytoplasmic E74A RNA but decreased nuclear puff staining (Figure 3F). The decrease in nuclear puff staining at +1.5 AHE likely reflects reduced transcription due to diminishing systemic levels of ecdysone at this stage [15]. This data demonstrates that the ecdysone-dependent transcription of E74A is not properly repressed in belpsg9 mutant glands, resulting in increased levels of E74A transcripts. The accumulating cytoplasmic RNA indicates that belpsg9 does not affect nuclear export of E74A mRNA. In addition, given that the E74A qPCR primers span an intron, belpsg9 does not appear to disrupt E74A pre-mRNA splicing. E75A and BR-C mRNA expression profiles show a relatively minor effect on their post-ecdysone pulse levels in belpsg9 mutant glands (Figure 2). Thus, belpsg9 has a strong and specific effect on the regulation of E74A transcription.

belle directly regulates translation of E74A

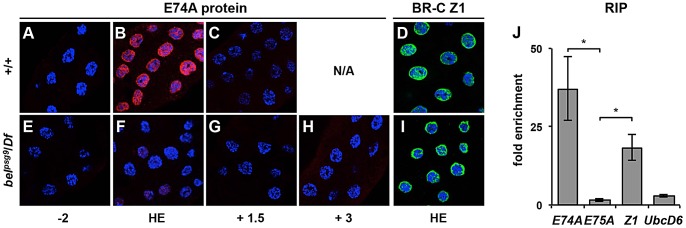

The failure to repress E74A transcription observed in belpsg9 salivary glands demonstrates that transcriptional regression of an ecdysone early response gene can be selectively disrupted in vivo. This result is reminiscent of organ culture studies describing effects of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide on ecdysone-induced puffs in salivary gland polytene chromosomes [16]. These classical experiments demonstrated that cycloheximide did not affect induction of ecdysone early response puffs but blocked their regression, leading Ashburner to propose a model in which the protein products of early response genes repress their own transcription [1]. Based on this model, we predicted that belle was required for E74A mRNA translation and that failure to repress E74A transcription was due to lack of E74A protein. To test this hypothesis, we used antibodies directed to E74A protein to stain salivary glands dissected from appropriately staged control and belpsg9 mutant pupae. In control salivary glands, E74A protein is expressed as a pulse at head eversion, with little expression 2 hours earlier or 1.5 hours later (Figure 4A–4C). As predicted, E74A protein is barely detectable in belpsg9 mutant salivary glands at head eversion (Figure 4F). Even at +3 AHE, when control salivary glands are too fragile to dissect and persistent belpsg9 mutant salivary glands have very high levels of E74A mRNA, E74A protein is still not detected (Figure 4H). Consistent with these observations, western blots of whole animal extracts from control and belpsg9 mutant pupae at head eversion showed a strong reduction in E74A protein (Figure S2A). Importantly, belle does not disrupt translation of other ecdysone-induced early response genes. Antibodies directed to BR-C common and Z1 specific isoforms show expression in control and belpsg9 mutant salivary glands (Figure 4D, 4I and data not shown). The cytoplasmic localization of Belle protein in both control and belpsg9 mutant salivary glands (Figure S2B and S2C) is consistent with a role in translational control. These results indicate that belle is required for translation of E74A protein.

Figure 4. Belle directly regulates E74A mRNA translation.

(A–I) Salivary glands dissected from animals staged relative to head eversion and stained with antibodies directed to E74A protein shown in red (A–C and E–H) or to BROAD Z1 protein in green (D, I) with DAPI costained nuclei in blue. (A–C) In control salivary glands, E74A protein is detected at head eversion (HE)(B), but not 2 hours before HE (A) or 1.5 hours AHE (C) (N/A: control glands are too fragile to dissect after +1.5 AHE). (E–H) In belpsg9 mutant salivary glands, E74A protein is barely detectable at stages before, during or after head eversion. (D–I) In contrast, both control and belpsg9 mutant salivary glands express BROAD Z1 protein at head eversion. (J) Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) immunoprecipitation (RIP) experiments with BEL-GFP fusion protein, followed by qPCR analysis for target mRNAs. E74A and BR-C Z1 transcripts showed significant (37-fold and 18-fold, respectively) enrichment in BEL-GFP containing RNP complexes, while E75A and UbcD6 transcripts did not show significant enrichment. Data represent average qPCR results from three independent RIP experiments; asterisks indicate p-values <0.05. HE: head eversion, Z1: BR-C Z1.

We then performed RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation (RIP) experiments to test if E74A mRNA is a direct target of Belle protein. We used extracts from appropriately staged animals carrying a GFP exon trap in belle: the resulting BEL-GFP fusion protein in these animals (belGFP-ZCL1911) is driven under the control of belle's own promoter [17], generates a protein of expected size and does not disrupt belle function (Figure S3A–S3B and data not shown). Antibodies directed to GFP were used to immunoprecipitate (IP) BEL-GFP containing ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes which were analyzed by RT-PCR (semi-quantitative) or qPCR (quantitative) to test for enrichment of associated mRNAs. Western blots showed effective pulldown of BEL-GFP from lysates (Figure S3C), subsequent semi-quantitative RT-PCR showed that anti-GFP antibodies preferentially immunoprecipitate E74A mRNA from lysates containing BEL-GFP (Figure S3D). For quantitative RIP analysis, lysates from belGFP-ZCL1911 animals were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by qPCR for relative enrichment of target RNAs. We chose the ecdysone early response gene E75A and the house-keeping gene UbcD6 (FBgn0004436) as controls because their endogenous levels were about 2-fold higher than those of E74A RNA (Figure S3E) and thus were similarly available potential targets of BEL-GFP. Quantitative analysis from three independent RIP experiments showed that BEL-GFP binding to E74A transcripts had an average 37-fold enrichment, while E75A and UbcD6 did not show significant enrichment (Figure 3J). Interestingly, BR-C Z1 mRNA also associates with Belle-containing RNPs even though its translation is not affected in belpsg9 mutant glands. Taken together, our results indicate that belle directly regulates translation of E74A mRNA.

E74A protein inhibits ecdysone-triggered E74A transcription

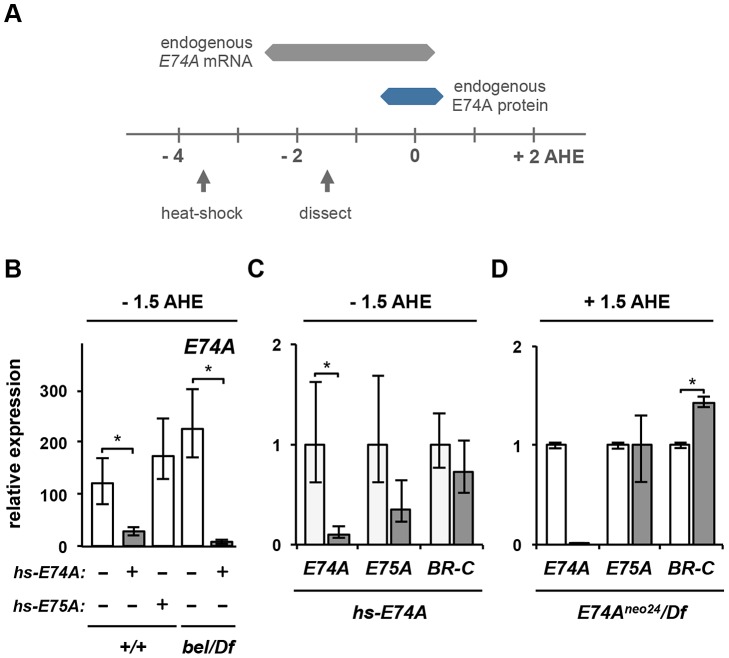

If accumulation of E74A mRNA in belpsg9 mutant salivary glands is due to the absence of E74A protein, then ectopic E74A protein should be sufficient to repress the ecdysone-induced transcription of E74A. To test this hypothesis, we used a transgenic construct expressing the E74A open reading frame, without its endogenous untranslated regions (UTR), under the control of the heat-shock promoter [18]. The expectation was that hs-E74A-derived transcripts, removed from their normal translational regulatory context, would circumvent the requirement for belle. Control and belpsg9 mutant animals carrying the hs-E74A transgenic construct were heat-shocked at −3.5 AHE and allowed to develop for two hours until −1.5 AHE (experimental paradigm illustrated in Figure 5A). Salivary glands do not express E74A protein at −1.5 AHE (Figure S4A); however, heat-shocked control and belpsg9 mutant animals carrying hs-E74A express E74A protein in salivary glands (Figure S4B and S4C). Ecdysone-induced expression of endogenous E74A mRNA (distinguished from hs-E74A-derived RNA with 5′UTR specific qPCR primers) is at or near its highest levels at −1.5 AHE; however, ectopic expression of E74A protein at this stage inhibits endogenous E74A mRNA expression in salivary glands (Figure 5B). This inhibition was specific to E74A protein because a similar experiment with heat-shock-induced expression of E75A protein does not repress E74A transcription (Figure 5B). In belpsg9 mutant animals, expression of E74A protein is also sufficient to inhibit ecdysone-induced transcription of E74A (Figure 5B). These results suggest that, as predicted by Ashburner, the protein product of the early response gene E74A represses its own ecdysone-induced transcription.

Figure 5. E74A protein is sufficient to inhibit its own ecdysone-induced transcription.

(A) Experimental paradigm for expressing E74A protein prior to the prepupal pulse of ecdysone. Expression profile of endogenous E74A mRNA (in gray) and E74A protein (in blue) in salivary glands shown relative to hours after head eversion (AHE). Arrows mark timing of the 30 minute heat-shock treatment and the subsequent dissection of larval salivary glands. (B) Precocious expression of E74A protein (gray bars) is sufficient to repress induction of endogenous E74A mRNA in control and belpsg9 mutant salivary glands. Control salivary glands show over 100-fold induction of E74A in response to the prepupal pulse of ecdysone (first bar from left). In contrast, ectopic expression of E74A protein (second bar), but not E75A protein (third bar), inhibits endogenous E74A transcription. Similarly, ectopic E74A protein inhibits the ecdysone-induced expression of E74A in belpsg9 mutant salivary glands (fourth and fifth bars). (C) Although precocious expression of E74A protein is sufficient to repress the ecdysone-induced transcription of E74A, it has a minor effect on the expression of ecdysone early response genes E75A and BR-C Z1. Salivary glands dissected from heat-shock-treated control (white bars) and hs-E74A carrying (gray bars) animals. (D) E74A is not necessary for the regression of other ecdysone early response genes. Salivary glands dissected from control (white bars) and E74Aneo24/Df mutant (gray bars) animals at +1.5 AHE, when endogenous expression of early response genes E75A and BR-C have regressed to levels prior to the ecdysone pulse. E74Aneo24 allele is an RNA null, hence the barely detectable levels of endogenous E74A mRNA. y-axis plots relative expression, normalized to rp49. Expression ratios in 5B calculated relative to −4 AHE control samples to show induction in response to the prepupal pulse of ecdysone. All samples are in triplicate; asterisks indicate p-values <0.05. bel/Df: belpsg9/Df. AHE: after head eversion.

Implicit in Ashburner's original model was that protein products of each early gene repress their own transcription [1]. Experimental manipulations of gene dosage performed by Walker and Ashburner are consistent with the idea that E74A and E75A early genes are auto-regulated: adding a copy of the 74EF-75B region results in puffs that regress more rapidly, while removing a copy of the region results in puffs that take longer to regress [19]. Accordingly, E74A and E75A proteins have been shown to bind their own promoters [20], [21]. However, in addition to binding their own ecdysone-induced puffs on polytene chromosomes, E74A and E75A proteins show strong binding to each other's puffs [20], [22], raising the possibility of an alternate model in which early response genes repress each other. To distinguish between these auto-inhibitory and cross-inhibitory models, we measured expression of the three classical early response genes (E74A, E75A and BR-C) in salivary glands dissected from hs-E74A-treated and from E74A mutant pupae. Although expression of E74A protein prior to the prepupal pulse of ecdysone has a dramatic effect on induction of E74A mRNA, it does not have a significant effect on either E75A or BR-C induction (Figure 5C). Conversely, salivary glands dissected from E74A-specific RNA null mutant (E74Aneo24/Df) pupae at +1.5 AHE showed no effect on the regression of E75A expression and a minor effect on regression of BR-C (Figure 5D). Thus, our data suggests that although cross-inhibitory regulation may occur, auto-inhibition appears to be the primary mechanism for the self-limiting behavior of ecdysone early response genes like E74A.

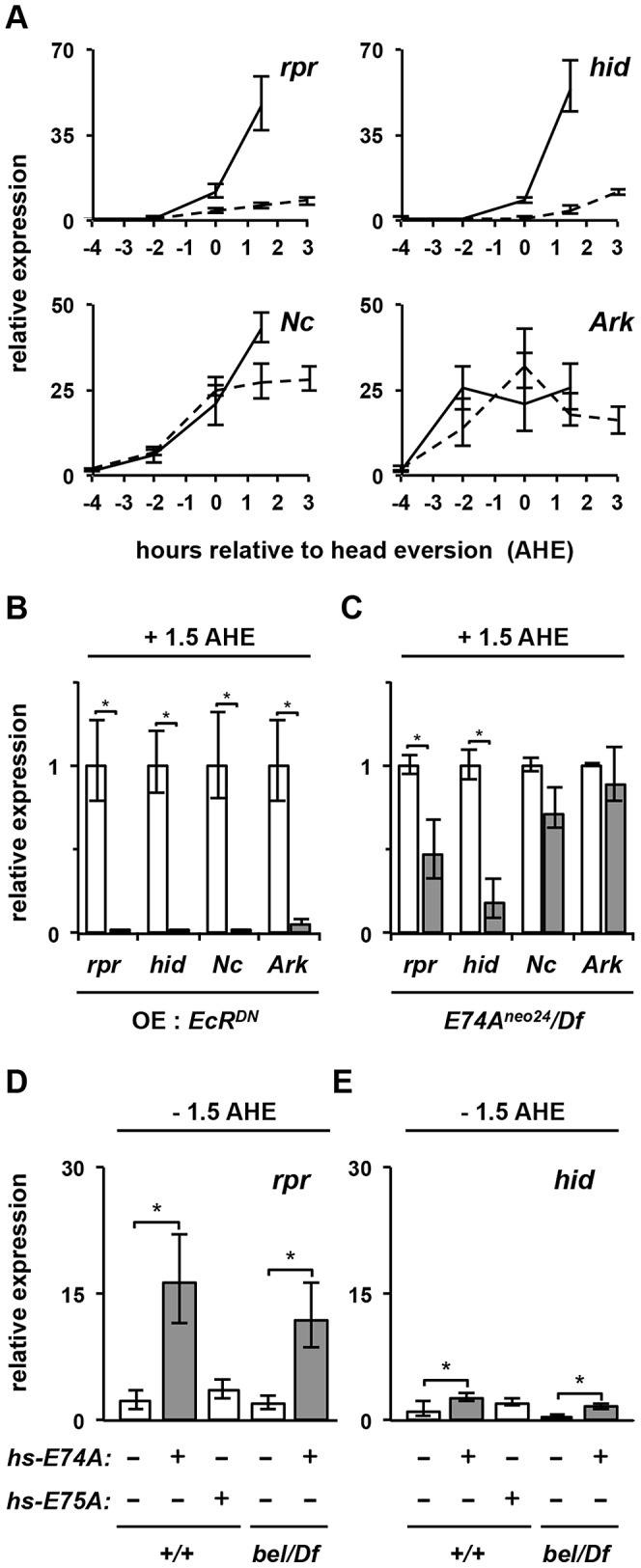

belle and E74A selectively disrupt ecdysone-triggered expression of rpr and hid

To demonstrate that belle disrupts E74A-dependent ecdysone responses, we characterized the ecdysone-triggered death response in belpsg9 mutant salivary glands. The destruction of larval salivary glands is triggered, at least in part, by expression of death activators rpr and hid in response to the prepupal pulse of ecdysone [23]. As expected, rpr and hid are induced in control salivary glands by the prepupal pulse of ecdysone, showing expression beginning at head eversion (0 AHE) and reaching 50-fold induction 1.5 hours later (+1.5 AHE) (Figure 6A). Salivary glands from belpsg9 mutant animals, however, do not show induction of either rpr or hid (Figure 6A), suggesting that belpsg9 acts upstream of death activator expression in the ecdysone-triggered transcriptional cascade. Expression of the Drosophila Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein (diap1) (FBgn0260635) is not affected in mutant salivary glands (data not shown). In addition, belpsg9 does not affect the ecdysone-induced expression of other death genes at this stage. The apical caspase Nc (FBgn0026404) and the caspase adaptor Ark (FBgn0263864)(homologs of the vertebrate caspase-9 and Apaf-1, respectively) are also induced during the death response in salivary glands [4], [24]–[26]. However, Nc and Ark are properly induced in belpsg9 mutant salivary glands (Figure 6A), suggesting that belpsg9 selectively disrupts expression of rpr and hid in response to the prepupal pulse of ecdysone. Expression of a dominant negative ecdysone receptor immediately prior to head eversion blocks salivary gland-specific expression of rpr, hid, Nc and Ark (Figure 6B), confirming that these genes are induced in response to the prepupal pulse of ecdysone. Three components of the ecdysone hierarchy have been shown to disrupt the death response in larval salivary glands: BR-C[rbp5], E74A and E93 [3]–[5]. Of these, BR-C[rbp5] and E93 affect expression of Nc and/or Ark [4], [5], [27]. On the other hand, salivary glands dissected from E74A-specific null mutant (E74Aneo24/Df) pupae at +1.5 AHE show a significant reduction in levels of both rpr and hid, without any effects on expression of Nc or Ark (Figure 6C). Thus, like belpsg9, E74A selectively regulates rpr and hid expression, demonstrating that the effects of belpsg9 during the ecdysone-induced death response in salivary glands are mediated primarily by belle's effects on E74A protein. Moreover, E74A mutant animals have very similar phenotypes to those described above for belpsg9, with mutant animals dying after head eversion and showing a highly penetrant PSG phenotype (data not shown and [3], [7], [28]). Together, our data suggest that belpsg9 disrupts expression of E74A-dependent ecdysone late genes.

Figure 6. Expression of E74A protein–dependent ecdysone late-response genes is disrupted in belle glands.

(A) belpsg9 is required for ecdysone-induced expression of death activators rpr and hid, but not Nc and Ark. x-axis plots timecourse of salivary glands dissected from control (solid lines) and belpsg9/Df (dashed lines) animals staged relative to head eversion (AHE) (salivary glands cannot be recovered from control animals after +1.5 AHE). (B) Ectopic expression of dominant negative ecdysone receptor prior to the prepupal pulse of ecdysone blocks expression of death regulators rpr, hid, Nc, and Ark in salivary glands. Control (white bars) and OE: EcRDN (UAS-GAL4/UAS-EcRF645A; hs-GAL4/+) (gray bars) preupupae were heat-shocked four hours before head eversion (−4 AHE), re-staged at head eversion and salivary glands were dissected at +1.5 AHE, a stage when these death genes are maximally expressed. (C) E74A is required for ecdysone-induced expression of death activators rpr and hid, but not Nc and Ark. Relative expression of death regulators in salivary glands dissected from control (white bars) or E74Aneo24/Df mutant (gray bars) animals. (D–E) Precocious expression of E74A protein (gray bars) is sufficient to significantly induce expression of rpr (D) and hid (E) in salivary glands (experimental paradigm as Figure 5A). (D) Ectopic expression of E74A protein in control (second bar from left) and belpsg9 mutant (fifth bar from left) animals show significant induction of rpr. In contrast, ectopic expression of E75A protein (third bar from left) does not show any effect. (E) Similar experiments measuring hid expression show minor but statistically significant changes. y-axis plots relative expression, normalized to rp49. Expression ratios in 6D and 6E calculated relative to −4 AHE control samples to show induction in response to the prepupal pulse of ecdysone. All samples are in triplicate; asterisks indicate p-values <0.05. bel/Df: belpsg9/Df. AHE: after head eversion.

E74A protein rescues rpr expression in belle glands

To demonstrate that belle's effects on E74A-dependent targets are mediated by E74A protein, we expressed E74A protein in control and belpsg9 mutant salivary glands using the hs-E74A transgenic construct (using paradigm described in Figure 5A). Control salivary glands have very low levels of rpr and hid mRNA at −1.5 AHE; in contrast, precocious expression of E74A protein resulted in a significant induction of rpr (Figure 6D). This effect was specific to E74A protein, since the expression of E75A protein under the same conditions did not have any effect on rpr expression (Figure 6D). Importantly, in belpsg9 mutant glands, like in control glands, E74A protein was sufficient to precociously induce rpr (Figure 6D). Although E74A is necessary for hid expression (Figure 6C), precocious E74A protein had a reduced but significant effect on hid expression in both control and mutant glands (Figure 6E), suggesting that ecdysone-dependent regulation of hid is more complex than that of rpr. Our attempts to use hs-E74A to experimentally rescue the PSG phenotype in belpsg9 mutant animals failed, suggesting that E74A protein alone is not sufficient for tissue destruction. Alternatively, Belle may have other targets required for a proper death response in salivary glands. Importantly, however, our expression analysis results demonstrate that E74A protein is sufficient to rapidly rescue the loss of ecdysone-induced expression of rpr in belpsg9 mutant glands.

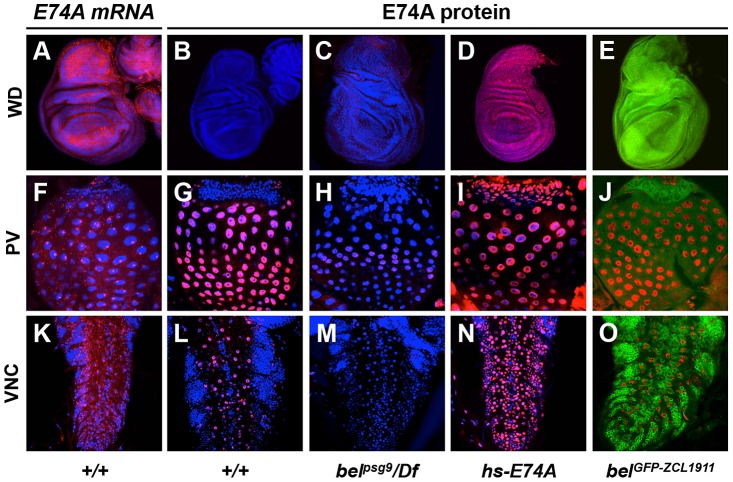

Translational, not transcriptional, control determines E74A protein distribution

Translational control is a critical mechanism for ensuring proper distribution and subcellular localization of proteins during development [29]. To understand why the ecdysone early response gene E74A was under belle-dependent translational control, we examined tissue-specific distribution of E74A mRNA and protein in response to the late larval pulse of ecdysone at the onset of metamorphosis. All tissues examined showed ubiquitous expression of E74A mRNA (wing imaginal discs, proventriculus and ventral nerve cord shown; Figure 7, first column). In contrast, E74A protein showed distinct cell- and tissue-specific expression patterns (Figure 7, second column). Imaginal wing discs, for example, do not show any E74A protein expression despite robust expression of E74A mRNA (Figure 7B), while the proventriculus (PV) and ventral nerve cord (VNC) showed E74A protein expression in a subset of cells (Figure 7G and 7L). Consistent with our observations, a previous study reported that in one tissue (the proliferation zone in the brain at the onset of metamorphosis), E74A protein was not detected despite presence of E74A mRNA [30], suggesting that E74A mRNA was under translational control. Importantly, we showed belpsg9 mutant tissues disrupted E74A protein expression in all tissues examined (Figure 7, third column), demonstrating that belle-dependent translational control regulates E74A protein in most, if not all, tissues. Moreover, heat-shock treatment of animals carrying the hs-E74A construct is sufficient to express E74A protein in cells that normally do not express it (Figure 7, fourth column). Belle protein is ubiquitously expressed in all tissues examined (Figure 7, fifth column, and data not shown), suggesting that the distribution of Belle alone does not determine where E74A mRNA is translated. Cells that do not express E74A protein appear to have higher levels of Belle; however, differences in levels of Belle protein are not sufficient to explain the spatial distribution of E74A protein. For example, reducing the level of Belle protein in VNC neurons or in wing discs does not alter the ability to translate E74A mRNA (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that regulation of translation, not of transcription, determines the tissue-specific distribution of E74A protein in response to systemic pulses of ecdysone. The mechanisms that regulate Belle-dependent translation of E74A mRNA in a cell-type- and tissue-specific manner, however, are yet to be determined.

Figure 7. Translational control determines spatial distribution of E74A protein.

Tissues at the onset of metamorphosis were dissected and imaged to detect E74A mRNA (in red, first column), E74A protein (in red, second through fifth columns) or Belle protein (in green, fifth column). Although ecdysone-induced transcription of E74A mRNA appears to be ubiquitously expressed (first column), E74A protein is not (second column). This spatial distribution of E74A protein is disrupted in belpsg9 mutant animals (third column) and becomes ubiquitous after expression of E74A protein from the hs-E74A transgene (fourth column). E74A protein is detected in the large cells of the proventriculus (G) and repo-positive glial cells in the ventral nerve cord (L and data not shown), but absent in the entire imaginal wing discs (B), the imaginal ring of the proventriculus (G) and neurons in the ventral nerve cord (L). Endogenous Belle protein, visualized with the belGFP-ZCL1911 exon trap, is expressed in all cells including those that do not express E74A protein (fifth column). Staining with antibodies directed to Belle protein show identical expression patterns (data not shown). For in situ hybridizations, tissues were dissected from animals a few hours before puparium formation (clear gut stage) when E74A mRNA levels are their highest. For E74A protein and BEL-GFP imaging, tissues were dissected at puparium formation when E74A protein levels are at their highest. DAPI costained nuclei in blue. WD: imaginal wing discs, PV: proventriculus, VNC: ventral nerve cords.

Discussion

Systemically released steroid hormones trigger transcriptional cascades that ultimately direct tissue-specific biological responses. This work demonstrates that translational control mechanisms play a critical role in refining steroid-triggered transcriptional responses (Figure 8). The DEAD box RNA helicase belle directly and selectively regulates translation of the ets transcription factor and classical ecdysone early response gene, E74A. As a result, in belle mutant cells, components of the ecdysone transcriptional cascade downstream of E74A are not regulated properly. In addition to regulating these E74A-dependent ecdysone late response genes, E74A protein also inhibits its own ecdysone-induced transcription. Moreover, although E74A is a ubiquitous transcriptional target of ecdysone signaling, E74A protein is only expressed, in a belle-dependent manner, in a subset of cells. Thus, one property of this belle-dependent translational control is the ability to provide spatial specificity to systemic pulses of ecdysone.

Figure 8. Translational control by Belle regulates E74A-dependent ecdysone-triggered responses.

A model of how Belle protein regulates a subset of ecdysone-triggered transcriptional responses. E74A protein has two functions: to induce expression of E74A-dependent target genes and to inhibit its own ecdysone-induced transcription. Given that Belle is required for translation of E74A mRNA, Belle activity effectively regulates E74A-dependent targets within the ecdysone-triggered transcriptional cascade. Moreover, Belle-dependent translational control of a ubiquitous transcriptional target of ecdysone like E74A occurs in a tissue-specific manner, adding a novel regulatory layer to steroid hormone signaling. Thus, Belle-dependent translational control helps refine global ecdysone signals into distinct tissue-specific transcriptional responses.

belle/DDX3 DEAD box RNA helicases regulate many aspects of RNA metabolism, including splicing, nuclear export and translation; however, the mutation we identified specifically disrupts belle's ability to regulate translation. The lesion in belpsg9 affects the belle/DDX3 family-specific post II region. The adjacent DEAD box-containing motif II is critical for ATP-hydrolysis-dependent release of translationally repressed RNP complexes [8]; thus, a mutation in the yeast Ded1 DEAD box acts as a strong repressor of translation when overexpressed [9]. Similarly, previously identified mutations in the post II region in Ded1 also disrupt translation [14]. The requirement for both motif II and post II regions in translation initiation suggests these regions may act together to regulate translation. One model suggests that changes in the post II region may alter the position of the DEAD box, affecting the ability to hydrolyze ATP [31]. Importantly, however, although E74A protein is barely detectable in belpsg9 mutant animals, suggesting a strong block in translation, pre-mRNA splicing and nuclear export of E74A mRNA are not affected. These results indicate that the post II region-dependent activity, although critical for translational control, may not be required for other putative functions of Belle.

Our data suggest that belle is a selective regulator of translation. Within the ecdysone genetic hierarchy, for example, belle-containing RNPs associate with E74A mRNA but not with E75A mRNA. There is evidence that Belle/DDX3 proteins preferentially regulate translation of transcripts with long and complex 5′UTRs [32], [33], suggesting that target mRNA selection is mediated through interactions with 5′UTRs. Accordingly, E74A mRNA has a very long 5′UTR (1.9 kb) [34], whereas E75A mRNA has a much shorter 5′UTR (0.69 kb) [35]. Binding alone, however, does not indicate a role in translation initiation: belle-containing RNPs include BR-C Z1 mRNA, but BR-C Z1 protein is not affected in belpsg9 mutant tissues. Although it is possible that BR-C Z1 mRNA has redundant translation initiation mechanisms, this result is consistent with results from human cells where some DDX3 bound mRNAs do not require DDX3 for translation initiation [36]. It remains to be determined how this functional specificity among belle/DDX3 targets is regulated.

The selective disruption of E74A mRNA translation in belle mutant animals provided a unique opportunity to directly test a model proposed by Ashburner nearly 40 years ago to explain the temporal behavior of ecdysone-induced puffs in salivary gland polytene chromosomes. According to this model, the gene products of ecdysone early response puffs have two critical functions: initiate expression of subsets of late response genes and inhibit their own ecdysone-induced expression. Indeed, all three classical early puff loci (2B5[BR-C], 74EF and 75B) encode transcription factors which, in turn, regulate ecdysone late response genes [2]. This study shows that E74A protein is required for transcription of a subset of ecdysone-triggered late genes in salivary glands. Importantly, we have demonstrated for the first time that the transcription of an ecdysone early response gene is auto-regulated, fulfilling the second prediction of the Ashburner model. E74A protein is both necessary and sufficient to inhibit its own transcription. In the absence of E74A protein, as in belpsg9 mutant salivary glands, ecdysone-induced transcription fails to regress and transcripts continue to accumulate to very high levels; conversely, ectopic expression of E74A protein inhibits E74A transcription in both control and belpsg9 mutant salivary glands. Given that E74A protein can bind in vitro to DNA sequences within the E74A locus [20], the effect of E74A protein on E74A transcription is likely to be direct. In addition, we observe the effect of ectopic E74A protein on E74A transcription in whole animal extracts from control and mutant prepupae (data not shown), indicating that E74A auto-regulation is not limited to salivary glands.

We propose that belle-dependent translational control provides specificity to ecdysone signaling by regulating a subset of ecdysone early response genes. This conclusion is supported by multiple lines of evidence. First, antibody staining experiments indicate that belpsg9 disrupts translation of E74A mRNA but not of BR-C mRNA. Second, RNA binding protein immunoprecipitation experiments indicate that Belle protein selectively associates with a subset of ecdysone early genes. Third, auto-regulation of E74A transcription is strongly disrupted in belpsg9 mutant salivary glands with minor effects on the other early genes, consistent with a selective translation defect. Fourth, belpsg9 disrupts a subset of ecdysone-triggered responses at the onset of metamorphosis that is different from those of BR-C or E75A mutant animals, but indistinguishable from those of E74A mutant animals. Taken together, these results suggest that among the three classical ecdysone early response genes–E74A, E75A and BR-C–only E74A mRNA translation is regulated by belle, giving belle the ability to determine E74A protein-dependent responses at the onset of metamorphosis.

Translational control of ecdysone-triggered responses provides new insight into mechanisms that refine systemic steroid signals into tissue-specific responses. Current explanations for how global hormonal cues are refined into distinct local responses invoke transcriptional mechanisms that regulate DNA binding properties of nuclear receptors, including availability of nuclear receptor co-factors or accessibility to nuclear receptor binding sites at target genes. Our observations, however, suggest that translational control can determine the spatial readout of ubiquitous transcriptional targets of liganded nuclear receptors, adding a previously unknown regulatory layer to steroid hormone signaling. Determining prevalence of translational control within steroid signaling pathways in other organisms and understanding how this belle/DDX3-dependent translational control is regulated are important goals for future studies.

Materials and Methods

Stocks and recombination mapping

The following stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center: bel6 (FBst0004024), belL4740 (FBst0010222), Df(3L)81k19 (FBst0002998), Df(3R)BSC197 (FBst0009623), Df(3R)Exel6149 (FBst0007628), Df(3R)p712 (FBst0001968), E74Aneo24 (FBst0010262), hs-GAL4 (FBst0001799), UAS-EcRF645A (FBst0006869) and UAS-GAL4 (FBst0005939). belGFP-ZCL1911 was obtained from Morin et al. 2001 [17]. belpsg9 stock was generated in Wang et al. 2008 [7]. Use of fkh-GAL4, UAS-GFP stock is described in Wang et al. 2008 [7]. C. Thummel kindly provided the hs-E74A and hs-E75A stocks. Recombination mapping of psg9 was conducted using pairs of dominant markers as described previously [7]. For experiments with E74A and belpsg9 hemizygous animals described in this report, we used the Df(3L)81k19 and Df(3R)Exel6149 chromosomal deficiencies, respectively.

Developmental staging

Animals were raised on cornmeal molasses media with granulated yeast at 25°C. For developmental staging during metamorphosis, animals were either synchronized at puparium formation (white prepupae) or at pupation (head eversion), placed on damp black filter paper in a Petri dish and aged appropriately at 25°C. For time points before head eversion, animals were staged at puparium formation and aged based on the average duration of prepupal development (time from white prepupae to head eversion). For staging late third instar larvae at the peak of the late larval ecdysone pulse, we used standard “blue food” technique to pick “clear gut” larvae [37]. For heat shock treatments, staged animals were placed on Parafilm-sealed grape agar plates and submerged in a 37.5°C water bath for 30 minutes. Lethal phases were assigned based on the staging criteria described by Bainbridge and Bownes [38]: P1–P3 for prepupae (PP), P4–P9 for pupa (P), P10–P15 for pharate adult (PA), and eclosed adults (A).

Quantitative RT–PCR

Each sample was prepared by extracting RNA from 16 salivary glands dissected from appropriately staged animals using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 400 ng of total RNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System with Oligo(dT)20 primers (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using a Roche 480 LightCycler with the LightCycler 480 DNA SYBR Green I Master kit (Roche). Cycling was performed with an annealing temperature of 59°C and a 6 second extension time; 3–5 ten-fold dilutions of pooled cDNA from samples spanning metamorphosis were used to calculate the amplification efficiency of primer pairs in each experiment. Roche LightCycler 480 Software (Version 1.5) was used to calculate cycle threshold values and melt curve analysis for each reaction. Relative Expression Software Tool (REST) was used to calculate relative expression and standard error [39]. REST uses an integrated randomization and bootstrapping method to calculate confidence intervals and p-values for relative expression ratios. Given that REST calculates standard error based on a confidence interval centered on the median, it reflects the asymmetrical tendencies of the data. Control and experimental condition were analyzed simultaneously with three independent biological samples for both reference (rp49) (FBgn0002626) and target genes. Expression ratios were normalized relative to the lowest point in each expression profile or to the paired control (except in Figure 5B, Figure 6D and 6E where control and experimental samples are normalized to −4 AHE control samples that were run simultaneously). Primer sequences are listed in Table S1.

RNA in situ hybridizations

Probe synthesis, tissue preparation, hybridization, and probe detection were carried out according to Wilk et al. 2010 [40]. Digoxigenin-labeled probes were synthesized by PCR amplification of E74A cDNA using E74A 5′UTR-specific primers (E74A-UTR F 5′-AGAAATCTCGCTGTTCAAGTGG, E74A-UTR R 5′-GCGGCCAAGCA AATACAACAA C). To detect probes after hybridization, tissues were incubated overnight at 4°C in 1∶400 HRP-conjugated mouse monoclonal α-DIG antibody (Jackson Immuno-Research Labs), followed by incubation in 1∶50 Cy3 tyramide conjugates (Perkin Elmer). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Stained tissues were mounted on slides with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories). Tissues from E74A mRNA null (E74AP[neo]/Df) mutant animals do not show staining, demonstrating specificity of probes to E74A mRNA (data not shown).

Immunofluorescence

Dissected tissues from appropriately staged animals were fixed and immunostained using standard methods as described previously [41]. Primary antibodies: 1∶50 mouse α-BR-C Z1, (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), 1∶200 rabbit α-BEL (a generous gift from P. Lasko), 1∶10 mouse α-E74A 11C9, 6C5.3 (a generous gift from C. Thummel). Secondary antibodies: 1∶200 Cy3 α-mouse, 1∶200 Cy3 α-rabbit (Jackson Immuno-Research Labs), 1∶200 AlexaFluor 488 α-mouse/rabbit, (Invitrogen). Stained tissues were mounted on slides with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories).

Microscopy and image capture

Lethal phase and persistent salivary gland images were obtained and captured using an Olympus SZX16 stereomicroscope coupled to an Olympus DP72 digital camera with DP2-BSW software (Olympus). RNA in situ hybridizations and immunofluorescence images were taken on an Olympus FLUOVIEW FV1000 confocal microscope with FV10-ASW software.

RNA immunoprecipitation

In a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube, 40 appropriately staged belGFP-ZCL1911 or control whole animals were flash frozen in 50 µl of LB150 (150 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1× Complete Mini–Protease Inhibitors (Roche), 0.04 u/µl RNasin – RNase inhibitors (Promega)). Samples were homogenized and 950 µl LB150 was added to each sample. Cleared extracts were transferred to fresh tubes. Immunoprecipitation (IP) using the direct method was performed with Dynabeads Protein G (Invitrogen) as recommended by the manufacturer. 5 µl rabbit α-GFP (Torrey Pines) was added to antibody (+) samples. Antibody (−) samples received no antibody. All washes were conducted using PBST/BSA (1× PBS, 0.5% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.04 u/µl RNasin in DEPC treated H20). After the elution of BEL-GFP-containing RNPs, samples were either subjected to RNA isolation or protein isolation depending on the downstream application. For qualitative assessment by RT-PCR, primer sets specific to E74A mRNA were amplified in immunoprecipitated samples and amplicons were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Gel images were captured using a UVP BioDoc-It system with UV transilluminator (UVP). For quantitative assessment by qPCR, three independent BEL-GFP lysates from −2 AHE were split into two fractions. The first fraction received anti-GFP (+). The second fraction did not (−). Upon elution IPed samples underwent RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and were analyzed by qPCR. To determine the copy number of each target gene, absolute quantification using LightCycler 480 Software (Version 1.5) (Roche) was performed by analyzing 7 ten-fold dilutions of an amplicon with a known concentration in parallel to immunoprecipitated samples of an unknown concentration. For E74A, E75A, Z1 and Ubcd6 enrichment was calculated by dividing the copy number in the (+) fraction over the (−) fraction.

Western blotting

10 whole animals were homogenized on ice in 150 µl of hi-salt lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3 V04, 5 µg/ml Pepstatin A, 1 mM DTT, 5 µg/ml Aprotinin, 200 µM PMSF, 10 µg/ml Leupeptin, 4 nM Microsystin). Samples containing equal amounts of protein in 4× sample buffer (1.0 M Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 8% SDS, 40% Glycerol, 20% 2-Mercaptoethanol) were separated on a 6–10% SDS-PAGE gel and were blotted by standard methods. Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA in PBST (1× PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100) and incubated with diluted primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies were diluted at 1∶1000 rabbit α-GFP (Torrey Pines), 1∶1000 rabbit α-β-actin (Cell Signaling Technologies), 1∶3000 mouse α-E74A (a gift from C. Thummel). Secondary antibodies were diluted to 1∶30,000 α-rabbit IgG alkaline phosphatase linked whole antibody (GE Healthcare) and α-mouse IgG alkaline phosphatase antibody (Sigma). Membranes were developed with ECF substrate (GE Healthcare) and were imaged using a Storm 840 Scanner (Amersham Bioscience) with ImageQuant TL software version 7.0 (GE Healthcare).

Supporting Information

Mapping and allelic series of belpsg9. (A) psg9 mapped by recombination analysis, complementation tests and Sanger sequencing. Recombination mapping with pairs of dominant markers placed psg9 in the Glued (Gl) – Hairless (H) region of the third chromosome: right of the Roughened (R) and Dichaete (D) pair and left of the Hairless (H) and Prickly (Pr) pair (see arrows; method described in [7]). Complementation tests with chromosomal deficiencies in this region mapped psg9, first to a large cytological deficiency (Df(3R)p712), then to a small region defined by two overlapping deficiencies (Df(3R)BSC197 and Df(3R)Exel6149). All publicly available lethal mutations of genes within the minimal region were crossed and multiple alleles of the DEAD-box helicase bel failed to complement psg9. Sanger sequencing identified lesions in both belpsg9 and bel6. (B) Lethal phase and persistent salivary gland (PSG) phenotype of belle hemizygous and transheterozygous animals. All belpsg9 hemizygous and transheterozygous mutant combinations die after head eversion (as pupae) and have a highly penetrant PSG phenotype. bel6 and belL4740 hemizygous and transheterozygous animals die prior to puparium formation. PSG was assayed at 24 hours after puparium formation when control animals have 0% PSG (n = 100). Early lethal: embryonic or first larval instar lethal, PP: prepupal lethal, P: pupal lethal, PA: pharate adult lethal, A: adult escapers, n/a - not applicable because mutants do not reach the appropriate stage for PSG assay.

(TIF)

E74A and Belle protein expression in belpsg9 mutants. (A) Western blots of whole animal extracts with antibodies directed to E74A protein. E74A protein is robustly expressed in control (left) but barely detectable in belpsg9 mutant animals (right) at head eversion. β-Actin used as a loading control. (B–C) Larval salivary glands stained with antibodies directed to Belle shown in red with DAPI costained nuclei in blue. Belle protein is cytoplasmic in both control (B) and belpsg9/Df mutant (C) salivary glands at head eversion (HE).

(TIF)

RNA binding protein immunoprecipitation experiments. (A) Schematic depicting the nature of the BEL-GFP protein trap line used (belGFP-ZCL1911) [17]. (B) Western blot analysis using antibodies directed to GFP (anti-GFP) detects a BEL-GFP fusion protein of the appropriate size in whole animal lysates (a GFP expressing line used as control). (C) Western blot analysis using anti-GFP detects BEL-GFP in whole animal lysates and in immunoprecipitated samples. As expected, immunoprecipitated BEL-GFP samples from whole animal lysates at −2 AHE enrich BEL-GFP protein. (D) Immunoprecipitated (IP) BEL-GFP containing RNPs detects enrichment of E74A transcripts using RT-PCR. Two methods were compared: extracts from control or Bel-GFP animals IP with anti-GFP antibodies (left lanes) or Bel-GFP extracts IP with and without anti-GFP antibodies (right lanes). Both approaches show strong enrichment of E74A mRNA in BEL-GFP RNPs. (E) Absolute quantification of mRNA copy number in whole animal lysates at −2 AHE. The copy number for E74A mRNA is the lowest compared to the other control genes, further supporting the enrichment in the RNA IP experiments.

(TIF)

Ectopic expression of E74A protein from the hs-E74A transgene in salivary glands. Staining with antibodies directed to E74A protein shown in red demonstrates that heat-shock (hs) driven induction of the hs-E74A transgene expresses E74A protein in both control (B) and belpsg9/Df mutant (C) salivary glands at a stage (1.5 hours before head eversion) when endogenous E74A protein is not present (A). Ectopic expression paradigm as described in Figure 5A. DAPI costained nuclei in blue.

(TIF)

qPCR primer sequences. The first column indicates the forward (F) and reverse (R) primer pair for each target gene. Second column shows sequence for each primer. Each primer pair was designed and validated in this study unless otherwise noted. Source references: (a) [42], (b) [43], (c) [44] and (d) [45].

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank the Bloomington Stock Center, FlyTrap, and C. Thummel for Drosophila stocks; DSHB, C. Thummel, and P. Lasko for antibodies; Nick Wleklinski for technical assistance; Sarah Neuman for critically reading the manuscript; Yunsik Kang and Sarah Neuman for helpful discussions.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by an NIGMS/NIH grant (R01GM095944) to AB. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Ashburner M, Chihara C, Meltzer P, Richards G (1974) Temporal control of puffing activity in polytene chromosomes. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 38: 655–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thummel CS (1996) Flies on steroids–Drosophila metamorphosis and the mechanisms of steroid hormone action. Trends Genet 12: 306–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jiang C, Lamblin AF, Steller H, Thummel CS (2000) A steroid-triggered transcriptional hierarchy controls salivary gland cell death during Drosophila metamorphosis. Molecular Cell 5: 445–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee CY, Wendel DP, Reid P, Lam G, Thummel CS, et al. (2000) E93 directs steroid-triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Molecular Cell 6: 433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee C (2002) Genetic Mechanism for the Stage- and Tissue-Specific Regulation of Steroid Triggered Programmed Cell Death in Drosophila. Dev Biol 252: 138–148 doi:10.1006/dbio.2002.0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ward RE, Reid P, Bashirullah A, D'Avino PP, Thummel CS (2003) GFP in living animals reveals dynamic developmental responses to ecdysone during Drosophila metamorphosis. Dev Biol 256: 389–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang L, Evans J, Andrews HK, Beckstead RB, Thummel CS, et al. (2008) A genetic screen identifies new regulators of steroid-triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Genetics 180: 269–281 doi:10.1534/genetics.108.092478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Linder P, Jankowsky E (2011) From unwinding to clamping - the DEAD box RNA helicase family. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12: 505–516 doi:10.1038/nrm3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hilliker A, Gao Z, Jankowsky E, Parker R (2011) The DEAD-Box Protein Ded1 Modulates Translation by the Formation and Resolution of an eIF4F-mRNA Complex. Molecular Cell 43: 962–972 doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johnstone O, Deuring R, Bock R, Linder P, Fuller MT, et al. (2005) Belle is a Drosophila DEAD-box protein required for viability and in the germ line. Dev Biol 277: 92–101 doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jones WK, Rawls JM (1988) Genetic and molecular mapping of chromosome region 85A in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 120: 733–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bender M, Turner FR, Kaufman TC (1987) A development genetic analysis of the gene regulator of postbithorax in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol 119: 418–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ambrus AM, Nicolay BN, Rasheva VI, Suckling RJ, Frolov MV (2007) dE2F2-independent rescue of proliferation in cells lacking an activator dE2F1. Mol Cell Biol 27: 8561–8570 doi:10.1128/MCB.01068-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Noueiry AO, Chen J, Ahlquist P (2000) A mutant allele of essential, general translation initiation factor DED1 selectively inhibits translation of a viral mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 12985–12990 doi:10.1073/pnas.240460897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riddiford L (1993) Hormones and Drosophila development. In: Bate M, Martinez-Arias A, editors. The Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor, NY. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, pp. 899–939.

- 16. Ashburner M (1974) Sequential gene activation by ecdysone in polytene chromosomes of Drosophila melanogaster. II. The effects of inhibitors of protein synthesis. Dev Biol 39: 141–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morin X, Daneman R, Zavortink M, Chia W (2001) A protein trap strategy to detect GFP-tagged proteins expressed from their endogenous loci in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 15050–15055 doi:10.1073/pnas.261408198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fletcher JC, D'Avino PP, Thummel CS (1997) A steroid-triggered switch in E74 transcription factor isoforms regulates the timing of secondary-response gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 4582–4586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Walker VK, Ashburner M (1981) The control of ecdysterone-regulated puffs in Drosophila salivary glands. Cell 26: 269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Urness LD, Thummel CS (1990) Molecular interactions within the ecdysone regulatory hierarchy: DNA binding properties of the Drosophila ecdysone-inducible E74A protein. Cell 63: 47–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Johnston DM, Sedkov Y, Petruk S, Riley KM, Fujioka M, et al. (2011) Ecdysone- and NO-mediated gene regulation by competing EcR/Usp and E75A nuclear receptors during Drosophila development. Molecular Cell 44: 51–61 doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hill RJ, Segraves WA, Choi D, Underwood PA, Macavoy E (1993) The reaction with polytene chromosomes of antibodies raised against Drosophila E75A protein. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 23: 99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yin V, Thummel C (2005) Mechanisms of steroid-triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Semin Cell Dev Biol 16: 237–243 doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee C-Y, Clough EA, Yellon P, Teslovich TM, Stephan DA, et al. (2003) Genome-wide analyses of steroid- and radiation-triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Curr Biol 13: 350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dorstyn L, Colussi PA, Quinn LM, Richardson H, Kumar S (1999) DRONC, an ecdysone-inducible Drosophila caspase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 4307–4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cakouros D, Daish TJ, Kumar S (2004) Ecdysone receptor directly binds the promoter of the Drosophila caspase dronc, regulating its expression in specific tissues. J Cell Biol 165: 631–640 doi:10.1083/jcb.200311057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cakouros D, Daish T, Martin D, Baehrecke EH, Kumar S (2002) Ecdysone-induced expression of the caspase DRONC during hormone-dependent programmed cell death in Drosophila is regulated by Broad-Complex. J Cell Biol 157: 985–995 doi:10.1083/jcb.200201034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fletcher JC, Burtis KC, Hogness DS, Thummel CS (1995) The Drosophila E74 gene is required for metamorphosis and plays a role in the polytene chromosome puffing response to ecdysone. Development 121: 1455–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kong J, Lasko P (2012) Translational control in cellular and developmental processes. Nat Rev Genet doi:10.1038/nrg3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boyd L, O'Toole E, Thummel CS (1991) Patterns of E74A RNA and protein expression at the onset of metamorphosis in Drosophila. Development 112: 981–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mohr G, Del Campo M, Turner KG, Gilman B, Wolf RZ, et al. (2011) High-throughput genetic identification of functionally important regions of the yeast DEAD-box protein Mss116p. J Mol Biol 413: 952–972 doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Berthelot K, Muldoon M, Rajkowitsch L, Hughes J, McCarthy JEG (2004) Dynamics and processivity of 40S ribosome scanning on mRNA in yeast. Mol Microbiol 51: 987–1001 doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Soto-Rifo R, Rubilar PS, Limousin T, de Breyne S, Décimo D, et al. (2012) DEAD-box protein DDX3 associates with eIF4F to promote translation of selected mRNAs. EMBO J doi:10.1038/emboj.2012.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Burtis KC, Thummel CS, Jones CW, Karim FD, Hogness DS (1990) The Drosophila 74EF early puff contains E74, a complex ecdysone-inducible gene that encodes two ets-related proteins. Cell 61: 85–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Segraves WA, Hogness DS (1990) The E75 ecdysone-inducible gene responsible for the 75B early puff in Drosophila encodes two new members of the steroid receptor superfamily. Genes Dev 4: 204–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lai M-C, Chang W-C, Shieh S-Y, Tarn W-Y (2010) DDX3 regulates cell growth through translational control of cyclin E1. Mol Cell Biol 30: 5444–5453 doi:10.1128/MCB.00560-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Andres AJ, Thummel CS (1994) Methods for quantitative analysis of transcription in larvae and prepupae. Methods Cell Biol 44: 565–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bainbridge SP, Bownes M (1981) Staging the metamorphosis of Drosophila melanogaster. J Embryol Exp Morphol 66: 57–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L (2002) Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucl Acids Res 30: e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wilk R, Murthy S, Yan H, Krause HM (2010) In Situ Hybridization: Fruitfly Embryos and Tissues. Curr Protoc Essential Lab Tech 4: 9.3.1–9.3.24. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yin VP, Thummel CS, Bashirullah A (2007) Down-regulation of inhibitor of apoptosis levels provides competence for steroid-triggered cell death. J Cell Biol 178: 85–92 doi:10.1083/jcb.200703206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Denton D, Shravage B, Simin R, Mills K, Berry D (2009) Autophagy, not apoptosis, is essential for midgut cell death in Drosophila. Current Biology 19: 1741–1746 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.042.Autophagy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chiang P-W, Kurnit DM (2003) Study of dosage compensation in Drosophila. Genetics 165: 1167–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Caldwell PE, Walkiewicz M, Stern M (2005) Ras activity in the Drosophila prothoracic gland regulates body size and developmental rate via ecdysone release. Current biology: CB 15: 1785–1795 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Agawa Y, Sarhan M, Kageyama Y, Akagi K, Takai M, et al. (2007) Drosophila Blimp-1 is a transient transcriptional repressor that controls timing of the ecdysone-induced developmental pathway. Molecular and cellular biology 27: 8739–8747 doi:10.1128/MCB.01304-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Mapping and allelic series of belpsg9. (A) psg9 mapped by recombination analysis, complementation tests and Sanger sequencing. Recombination mapping with pairs of dominant markers placed psg9 in the Glued (Gl) – Hairless (H) region of the third chromosome: right of the Roughened (R) and Dichaete (D) pair and left of the Hairless (H) and Prickly (Pr) pair (see arrows; method described in [7]). Complementation tests with chromosomal deficiencies in this region mapped psg9, first to a large cytological deficiency (Df(3R)p712), then to a small region defined by two overlapping deficiencies (Df(3R)BSC197 and Df(3R)Exel6149). All publicly available lethal mutations of genes within the minimal region were crossed and multiple alleles of the DEAD-box helicase bel failed to complement psg9. Sanger sequencing identified lesions in both belpsg9 and bel6. (B) Lethal phase and persistent salivary gland (PSG) phenotype of belle hemizygous and transheterozygous animals. All belpsg9 hemizygous and transheterozygous mutant combinations die after head eversion (as pupae) and have a highly penetrant PSG phenotype. bel6 and belL4740 hemizygous and transheterozygous animals die prior to puparium formation. PSG was assayed at 24 hours after puparium formation when control animals have 0% PSG (n = 100). Early lethal: embryonic or first larval instar lethal, PP: prepupal lethal, P: pupal lethal, PA: pharate adult lethal, A: adult escapers, n/a - not applicable because mutants do not reach the appropriate stage for PSG assay.

(TIF)

E74A and Belle protein expression in belpsg9 mutants. (A) Western blots of whole animal extracts with antibodies directed to E74A protein. E74A protein is robustly expressed in control (left) but barely detectable in belpsg9 mutant animals (right) at head eversion. β-Actin used as a loading control. (B–C) Larval salivary glands stained with antibodies directed to Belle shown in red with DAPI costained nuclei in blue. Belle protein is cytoplasmic in both control (B) and belpsg9/Df mutant (C) salivary glands at head eversion (HE).

(TIF)

RNA binding protein immunoprecipitation experiments. (A) Schematic depicting the nature of the BEL-GFP protein trap line used (belGFP-ZCL1911) [17]. (B) Western blot analysis using antibodies directed to GFP (anti-GFP) detects a BEL-GFP fusion protein of the appropriate size in whole animal lysates (a GFP expressing line used as control). (C) Western blot analysis using anti-GFP detects BEL-GFP in whole animal lysates and in immunoprecipitated samples. As expected, immunoprecipitated BEL-GFP samples from whole animal lysates at −2 AHE enrich BEL-GFP protein. (D) Immunoprecipitated (IP) BEL-GFP containing RNPs detects enrichment of E74A transcripts using RT-PCR. Two methods were compared: extracts from control or Bel-GFP animals IP with anti-GFP antibodies (left lanes) or Bel-GFP extracts IP with and without anti-GFP antibodies (right lanes). Both approaches show strong enrichment of E74A mRNA in BEL-GFP RNPs. (E) Absolute quantification of mRNA copy number in whole animal lysates at −2 AHE. The copy number for E74A mRNA is the lowest compared to the other control genes, further supporting the enrichment in the RNA IP experiments.

(TIF)

Ectopic expression of E74A protein from the hs-E74A transgene in salivary glands. Staining with antibodies directed to E74A protein shown in red demonstrates that heat-shock (hs) driven induction of the hs-E74A transgene expresses E74A protein in both control (B) and belpsg9/Df mutant (C) salivary glands at a stage (1.5 hours before head eversion) when endogenous E74A protein is not present (A). Ectopic expression paradigm as described in Figure 5A. DAPI costained nuclei in blue.

(TIF)

qPCR primer sequences. The first column indicates the forward (F) and reverse (R) primer pair for each target gene. Second column shows sequence for each primer. Each primer pair was designed and validated in this study unless otherwise noted. Source references: (a) [42], (b) [43], (c) [44] and (d) [45].

(DOCX)