Abstract

Manganese (Mn) is an essential element and it acts as a cofactor for a number of enzymatic reactions, including those involved in amino acid, lipid, protein and carbohydrate metabolism. Excessive exposure to Mn can lead to poisoning, characterized by psychiatric disturbances and an extrapyramidal disorder. Mn-induced neuronal degeneration is associated with alterations in amino acids metabolism. In the present study, we analyzed whole rat brain amino acid content subsequent to 4 or 8 intraperitoneal (ip) injections, with 25 mg MnCl2/kg/day, at 48-hour (h) intervals. We noted a significant increase in glycine brain levels after 4 or 8 Mn injections (p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively) and arginine also after 4 or 8 injections (p<0.001). Significant increases were also noted in brain proline (p<0.01), cysteine (p<0.05), phenylalanine (p<0.01) and tyrosine (p<0.01) levels after 8 Mn injections vs. the control group. These findings suggest that Mn-induced alterations in amino acid levels secondary to Mn affect the neurochemical milieu.

Index Entries: neurotoxicity, brain, manganese, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamate, amino acids

1. INTRODUCTION

Manganese (Mn) is an essential element; it acts as a cofactor in a number of enzymatic reactions, including those involved in amino acid, lipid, protein and carbohydrate metabolism [1,2]. Mn is an important cofactor for a variety of enzymes, including the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD E.C 1.15.1.1) [3], as well as enzymes involved in neurotransmitter synthesis and metabolism [4]. While Mn deficiency is extremely rare, toxicity subsequent to excessive Mn exposure is quite prevalent [5]. Mn poisoning induces psychiatric disturbances and an extrapyramidal disorder, referred to as manganism [6].

Classically, Mn neurotoxicity is characterized by deregulation of glutamatergic [7,8], γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAergic) [7,8,9,10] and dopaminergic (DAergic) [8,10,11] systems. Amino acids are not only indispensable for protein synthesis, but also play important cellular functions [12]. Amino acids such as glutamate, aspartate, proline, GABA, glycine, serine, β-alanine and taurine, play key roles as neurotransmitters and/or neuromodulators [13,14]. Arginine, glycine and cysteine are precursors of gaseous neurotransmitters, including nitric oxide (NO), carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), respectively. In addition, tyrosine, tryptophan and histidine act as precursors of dopamine, serotonin and histamine, respectively [15,16].

Intermediary metabolism processes are involved in the novo synthesis of brain amino acids [17]. Experimental studies demonstrate that Mn interferes with intermediary metabolic processes by inhibition of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) enzymes succinate dehydrogenase [18] and aconitase [19], leading to a subsequent decrease in the novo synthesis amino acids. In turn, this inhibition leads to decreased availability of reduced equivalents for oxidative phosphorylation and energy deficit. Zwingmann et al. [11] showed that the reduced neuronal energy state was associated with impaired de novo synthesis of glutamate and aspartate. However, they found also that Mn also stimulates glial pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and increases flux of TCA cycle through glial pyruvate carboxylase (PC), a key anaplerotic enzyme in brain [20]. Given these observations, the present study was undertaken to address the effects of Mn on a broad range of the amino acids that display a modulator/neurotransmitter role or are precursors of neurotransmitters.

2. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

Materials

Manganese chloride tetrahydrate (MnCl2·4H2O; 99.99%), for Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (GFAAS), was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Amino acid standards and other reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (Sigma Aldrich, Natick, MA). Nitric Acid (HNO3; 65%) and magnesium matrix modifier (Mg (NO3)26H2O (0.84 mol/L)), for GFAAS, were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

Animals and Treatment

Six-week-old male Wistar rats (180 ± 15 g), specific pathogen free, were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Barcelona, Spain) and maintained under standard environmental conditions. The animals were housed in a room, with 12-12h light/dark cycle, 50–70% humidity at 24°C. All experiments were performed in accordance with the Guiding Principles for the University’s Care and Use of Animals, University of Lisbon, Portugal. Rats received intraperitoneal (ip) injections of manganese chloride (MnCl2) or saline every 48 h. The rats were randomly divided into 3 groups as follows: (A) control (saline solution-treated) with 4 or 8 doses (n=6 each), (B) Mn 4 doses (25 mg/kg body weight, as MnCl2·4H2O, n=6), and (C) Mn 8 doses (25 mg/kg body weight, as MnCl2·4H2O, n=6). The dose of Mn was selected based on a rat toxicity study that reported brain Mn accumulation, as detected by Mn-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI) after 6 to 12 fractionated doses of MnCl2 (30 mg/Kg), administered at 48 h intervals [21]. The animals were euthanized with pentobarbital (20 mg/kg), 24 h after the last injection followed by cervical dislocation. The cerebral hemispheres were immediately removed and stored at −80°C until amino acids and Mn analyses were carried out.

Mn brain analyses

Brain Mn concentrations were determined by GFAAS, with a PerkinElmer Analyst™ 700 atomic absorption spectrometer equipped with an HGA Graphite Furnace and a programmable sample dispenser (AS 800 Auto Sampler). Prior to GFAAS analysis, brain samples were digested with an oxidizing acid mixture of 4:1 (v/v) suprapure nitric acid (65%):hydrogen peroxide, using a microwave-assisted acid digestion.

Brain amino acid analyses

Brain amino acid concentrations were measured according to a published method [22]. Tissues were homogenized in 0.1M trichloroacetic acid (TCA), containing 10−2 M sodium acetate and 10-4 M EDTA 5ng/ml isoproterenol (as internal standard) and 10.5% methanol (pH 3.8). Samples were spun in a microcentrifuge at 10,000 g for 20 minutes. The supernatant was removed and stored at −80°C. The pellet was saved for protein analysis. Next, the supernatant was thawed and spun for 20 minutes. Samples were reacted with 6-aminoquinol-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl carbamate, and alpha-aminobutyric acid was added as an internal standard. Samples were injected into a gradient high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Waters AccQ-Tag system) and separation of the amino acids was accomplished by means of a C18 reversed-phase column (Waters) and supplied buffers (A – 19% sodium acetate, 7% phosphoric acid,2% triethylamine, 72% water; B – 60% acetonitrile) using a specific gradient profile. Amino acids detected using this HPLC solvent system, eluted in the following order: cysteine, homocysteine, aspartate, serine, glutamate, glycine, taurine arginine, threonine, alanine, proline, GABA, cystine, tyrosine, valine, methionine, lysine, isoleucine, leucine, and phenylalanine. A scanning fluorescence detector (Waters 474) monitored the column elutant for amino acid fluorescence derivatives.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests. All analyses were carried out with GraphPad Prism 4.02 software for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Results were considered statistically significant at values p<0.05.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

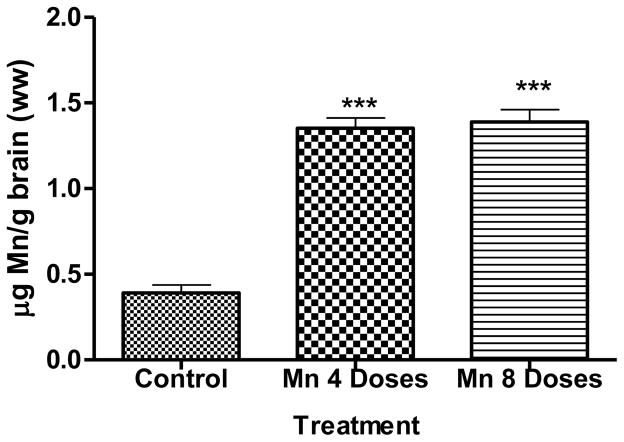

Brain Mn levels are shown in Figure 1. Significantly higher (p<0.001) brain Mn concentrations were observed in rats injected with 4 or 8 Mn doses compared with the control group. Mn accumulation in the brain did not increase in a dose-dependent manner and its concentration in the 4-dose Mn group was indistinguishable from the 8-dose Mn injected group. Our findings extend previous observations and establish that sub-acute ip Mn injections lead to increased brain Mn levels, reaching a plateau within 16 days (Figure 1). Corroborating studies, both in primates and rodents, our results also point to tight homeostatic control over brain Mn accumulation as even high exposures fail to increase brain Mn levels by ≥3 to 4 fold [23].

Fig. 1.

Brain Mn concentrationsin were obtained by GFAAS rats exposed to 4 or 8 doses of MnCl2 25 mg/Kg or saline solution, every 48 h, by ip route. Bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n=6). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, indicate statistical difference from control group by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests.

Brain amino acid concentrations are shown in Table 1. A dose-dependent significant increase in brain glycine was noted after 4- or 8- dose Mn injections (p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively); cysteine (p<0.05), phenylalanine (p<0.01) and tyrosine (p<0.01) levels were significantly increased only after 8-dose Mn injections. In addition, brain arginine was undetectable in controls, but was significantly increased in rats injected with either 4- or 8- Mn doses (p<0.001). Corroborating in part earlier observations [11,24,25].

Table 1. Concentration of rat brain amino acids.

Brain amino acid concentrations with recognized neurotransmitter/modulatory functions or precursors of neurotransmitters in the CNS, obtained by integration of the respective signals in HPLC spectra of brain tissue extracts, obtained from rats exposed to 4 or 8 doses of MnCl2 25 mg/Kg or saline solution, every 48 h, by ip route. of rats treated ip with 4 or 8 doses of MnCl2 25 mg/Kg and the control (C) group

| Amino acid | Control (pmol/μg protein) | MnCl2 25mg/kg per day (4 days) (pmol/μg protein) | MnCl2 25mg/kg per day (8 days) (pmol/μg protein) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taurine | 17.11 ± 4.16 | 11.98 ± 6.20 | 15.08 ± 3.58 |

| Alanine | 5.30 ± 0.98 | 4.38 ± 1.00 | 6.10 ± 0.84 |

| Glycine | 6.81 ± 0.69 | 10.37 ± 2.57* | 10.95 ± 2.27** |

| Serine | 3.93 ± 0.61 | 3.98 ± 1.34 | 4.44 ± 0.42 |

| Proline | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 0.54 ± 0.08 | 0.80 ± 0,08** |

| Arginine | 0.00 | 2.07 ± 1.04*** | 3.30 ± 0.25*** |

| Cysteine | 0.37 ± 0.19 | 0.45 ± 0.13 | 0.66 ± 0.09* |

| Tyrosine | 0.47 ± 0.06 | 0.47 ± 0.05 | 0.65 ± 0.11** |

| Histidine | 14.62 ± 2.31 | 12.71 ± 2.78 | 15.65 ± 4.16 |

| Phenylalanine | 0.46 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.05 | 0.69 ± 0.08** |

| GABA | 15.11 ± 2.31 | 14.12 ± 3.92 | 16.09 ± 2.26 |

| Glutamic acid | 34.37 ± 6.42 | 32.06 ± 10.75 | 35.87 ± 5.09 |

| Aspartic acid | 5.91 ± 1.07 | 6.58 ± 0.59 | 6.67 ± 0.98 |

Values of amino acid concentrations represent mean ± SEM (n=6).

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001, indicate statistical difference from control group by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests.

While central nervous system (CNS) Mn levels were similar in the 4- and 8- dose Mn injected groups, we noted significant increases in proline (p<0.01), cysteine (p<0.05) and tyrosine (p<0.01) levels after 8-dose Mn injections (Table 1). This effect may be secondary to replenishment of these amino acids, either by increased uptake by the blood-brain barrier or de novo synthesis [26]. It has yet to be determined whether levels of these transporters are altered in response to Mn treatment, potentially accounting for this effect.

We failed to observe statistically significant differences in brain GABA and glutamate brain levels between rats injected with Mn vs. saline. Reports on brain GABA concentrations in rat brain upon Mn exposure are inconsistent [9]. Some studies showed that sub-chronic exposure to Mn leads to decreased GABA [9,27]. Other studies showed significant increases in the cerebellar or striatal GABA [25,28].

We also analyzed amino acids levels of neurotransmitters precursors, such as cysteine, arginine, phenylalanine and tyrosine [15]. The 8-dose Mn group showed a significant increase in brain cysteine (p<0.05) and glycine (p<0.01) levels that might reflect increasing demand for glutathione (GSH). Notably, neurons rely on glial-borne cysteine for intraneuronal synthesis of the antioxidant GSH [29,30].

We noted a significant increase in glycine brain levels after 4 or 8 Mn injections (p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively). Glycine is a co-agonist of glutamate in NMDA receptors in brain stem, spinal cord, and cerebellum [12]. Takeda et al (2003) showed that Mn decreases extracellular glycine levels in the striatum of rats, injected with MnCl2 [31].

We also noted a significant increase in brain arginine levels (p<0.001) after 4 and 8 Mn injections. As arginine is a precursor of nitric oxide (NO) and Santos et al. (2002) found a significant increase in F4-NPs levels in 4-dose Mn group and F8-IsoPs in the 8-dose group [32], this effect may, account at least in part, be responsible for Mn-induced oxidative stress.

We noted also a significant increase in brain tyrosine and phenylalanine levels (p<0.01) after 8 Mn injections. Phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) catalyzes phenylalanine’s conversion to tyrosine. These findings may be explained by the inhibitory effect of Mn on dihydropteridine reductase (DHPR, E.C. 1.6.99.7) activity, as in its sulfate form, Mn has been shown in vitro to concentration-dependently decrease DHPR activity [33]. Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), a cofactor of PAH and aromatic amino acid hydroxylases enzymes involved in the synthesis of neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, is mainly regenerated by DHPR, thus a block in the BH4 pathway leads to the accumulation of phenylalanine and tyrosine [34].

Finally, we note that our study may have masked changes in amino acid levels post Mn exposure since the analysis was carried out in whole brains, thus potentially masking pronounced differences in areas that are known to accumulate high Mn concentrations, such as globus pallidus and striatum. In summary, the mechanisms underlying the effects of Mn on biochemical pathways should be further studied in order to better understand their role in mediating Mn-induced neurotoxicity.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by FCT (Foundation for Science and Technology of Portugal; SFRH/BD/64128/2009), by i-Med.UL, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Lisbon, and a grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences ES R01 10563 (MA).

References

- 1.Aschner J, Aschner M. Nutritional aspects of Mn homeostasis. MolAspectsMed. 2005:353–352. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erikson KM, Syversen T, Aschner JL, Aschner M. Interactions between excessive manganese exposures and dietary iron-deficiency in neurodegeneration. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;19:415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2004.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aschner M, Guilarte TR, Schneider JS, Zheng W. Manganese: recent advances in understanding its transport and neurotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;221:131–147. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golub MS, Hogrefe CE, Germann SL, Tran TT, Beard JL, et al. Neurobehavioral evaluation of rhesus monkey infants fed cow’s milk formula, soy formula, or soy formula with added manganese. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2005;27:615–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erikson KM, Thompson K, Aschner J, Aschner M. Manganese neurotoxicity: a focus on the neonate. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;113:369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aschner M, Erikson KM, Herrero Hernandez E, Tjalkens R. Manganese and its role in Parkinson’s disease: from transport to neuropathology. Neuromolecular Med. 2009;11:252–266. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8083-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagga P, Patel AB. Regional cerebral metabolism in mouse under chronic manganese exposure: implications for Manganism. Neurochem Int. 2012;60:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitsanakis VA, Au C, Erikson KM, Aschner M. The effects of manganese on glutamate, dopamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid regulation. Neurochem Int. 2006;48:426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erikson KM, Shihabi ZK, Aschner JL, Aschner M. Manganese accumulates in iron-deficient rat brain regions in a heterogeneous fashion and is associated with neurochemical alterations. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2002;87:143–156. doi: 10.1385/BTER:87:1-3:143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanwood GD, Leitch DB, Savchenko V, Wu J, Fitsanakis VA, et al. Manganese exposure is cytotoxic and alters dopaminergic and GABAergic neurons within the basal ganglia. J Neurochem. 2009;110:378–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zwingmann C, Leibfritz D, Hazell AS. Brain energy metabolism in a sub-acute rat model of manganese neurotoxicity: an ex vivo nuclear magnetic resonance study using [1–13C]glucose. Neurotoxicology. 2004;25:573–587. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koning T, Fuchs S, Klomp L. Serine, glycine and threonine. In: Lajtha A, editor. Handbook of neurochemistry and molecular neurobiology: amino acids and peptides in the nervous system. New York: Springer Science; 2007. pp. 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snyder SH, Logan WJ, Bennett JP, Arregui A. Amino acids as central nervous transmitters: biochemical studies. Neurosci Res (N Y) 1973;5:131–157. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-512505-5.50013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett JP, Jr, Logan WJ, Snyder SH. Amino acids as central nervous transmitters: the influence of ions, amino acid analogues, and ontogeny on transport systems for L-glutamic and L-aspartic acids and glycine into central nervous synaptosomes of the rat. J Neurochem. 1973;21:1533–1550. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb06037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boehning D, Snyder SH. Novel neural modulators. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2003;26:105–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baranano DE, Ferris CD, Snyder SH. Atypical neural messengers. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01716-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swanson T, Kim S, Glucksman M. Biochemistry, Molecular Biology & Genetics. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer - Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hietanen E, Kilpio J, Savolainen H. Neurochemical and biotransformational enzyme responses to manganese exposure in rats. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1981;10:339–345. doi: 10.1007/BF01055635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng W, Ren S, Graziano JH. Manganese inhibits mitochondrial aconitase: a mechanism of manganese neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 1998;799:334–342. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00481-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zwingmann C, Leibfritz D, Hazell AS. Energy metabolism in astrocytes and neurons treated with manganese: relation among cell-specific energy failure, glucose metabolism, and intercellular trafficking using multinuclear NMR-spectroscopic analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:756–771. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000056062.25434.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silva AC, Bock NA. Manganese-enhanced MRI: an exceptional tool in translational neuroimaging. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:595–604. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen SA, Michaud DP. Synthesis of a fluorescent derivatizing reagent, 6-aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl carbamate, and its application for the analysis of hydrolysate amino acids via high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1993;211:279–287. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erikson KM, Dobson AW, Dorman DC, Aschner M. Manganese exposure and induced oxidative stress in the rat brain. Sci Total Environ. 2004;334–335:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonilla E, Arrieta A, Castro F, Davila JO, Quiroz I. Manganese toxicity: free amino acids in the striatum and olfactory bulb of the mouse. Invest Clin. 1994;35:175–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipe GW, Duhart H, Newport GD, Slikker W, Jr, Ali SF. Effect of manganese on the concentration of amino acids in different regions of the rat brain. J Environ Sci Health B. 1999;34:119–132. doi: 10.1080/03601239909373187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yokel RA. Blood-brain barrier flux of aluminum, manganese, iron and other metals suspected to contribute to metal-induced neurodegeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;10:223–253. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-102-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandra SV, Malhotra KM, Shukla GS. GABAergic neurochemistry in manganese exposed rats. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 1982;51:456–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1982.tb01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai JC, Leung TK, Lim L. Differences in the neurotoxic effects of manganese during development and aging: some observations on brain regional neurotransmitter and non-neurotransmitter metabolism in a developmental rat model of chronic manganese encephalopathy. Neurotoxicology. 1984;5:37–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang J, Philbert MA. Cellular responses of cultured cerebellar astrocytes to ethacrynic acid-induced perturbation of subcellular glutathione homeostasis. Brain Res. 1996;711:184–192. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyons J, Rauh-Pfeiffer A, Yu YM, Lu XM, Zurakowski D, et al. Blood glutathione synthesis rates in healthy adults receiving a sulfur amino acid-free diet. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5071–5076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090083297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takeda A, Sotogaku N, Oku N. Influence of manganese on the release of neurotransmitters in rat striatum. Brain Res. 2003;965:279–282. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santos D, Milatovic D, Andrade V, Batoreu MC, Aschner M, et al. The inhibitory effect of manganese on acetylcholinesterase activity enhances oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in the rat brain. Toxicology. 2012;292:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altindag ZZ, Baydar T, Engin AB, Sahin G. Effects of the metals on dihydropteridine reductase activity. Toxicol In Vitro. 2003;17:533–537. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(03)00136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaufman S. New tetrahydrobiopterin-dependent systems. Annu Rev Nutr. 1993;13:261–286. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.13.070193.001401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]