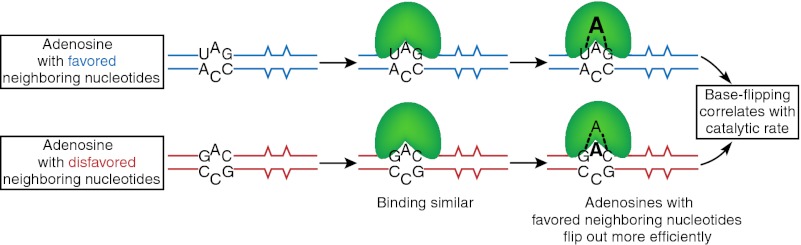

Fig. P1.

Model for the mechanistic basis of preferences. dsRNA containing an adenosine in a favored (UAG, blue), or disfavored (GAC, red), context is shown free or bound to human ADAR2 (green); the dsRNA includes mismatched bases (^) similar to those of an RNA used in our study. WT hADAR2 and all mutants tested bound dsRNA with a similar affinity regardless of whether the adenosine was in a favored or disfavored context, indicating that preferences do not arise from differential binding. Our data suggest that preferences are dictated in a subsequent “base-flipping” step, represented by dashed lines to an adenosine (A) flipped into the ADAR active site. Larger font size indicates that adenosines with favored neighbors are predominantly in the flipped-out state at equilibrium, whereas those with disfavored neighbors remain in the dsRNA helix. In our model, base flipping is a necessary step of the reaction, and, consistent with this assumption, a hADAR2 mutant with increased base-flipping capabilities has an increased catalytic rate.