Abstract

Background: fifteen percent of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) are elderly; they are less likely to have complications and more likely to have colonic disease.

Objective: to compare disease behaviour in patients with CD based on age at diagnosis.

Design: cross-sectional study.

Setting: tertiary referral centre.

Subjects: patients with confirmed CD.

Methods: behaviour was characterised according to the Montreal classification. Patients with either stricturing or penetrating disease were classified as having complicated disease. Age at diagnosis was categorised as <17, 17–40, 41–59 and ≥60 years. Logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the association between advanced age ≥60 and complicated disease.

Results: a total of 467 patients were evaluated between 2004 and 2010. Increasing age of diagnosis was negatively associated with complicated disease and positively associated with colonic disease. As age of diagnosis increased, disease duration (P < 0.001), family history of Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (P = 0.015) and perianal disease decreased (P < 0.0015). After adjustment for confounding variables, the association between age at diagnosis and complicated disease was no longer significant (OR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.21–1.65).

Conclusions: patients diagnosed with CD ≥60 were more likely to have colonic disease and non-complicated disease. However, the association between age at diagnosis and complicated disease did not persist after adjustment for confounding variables.

Keywords: Crohn's disease, aged, phenotype, inflammatory bowel disease, older people

Introduction

Crohn's disease (CD) is an idiopathic inflammatory disorder of the intestines usually diagnosed in the second or third decade of life; however, European studies report a second incidence peak occurring later in life [1–4]. Lapidus et al. found that the mean age of diagnosis increased from 25 years in 1955 to 32 years of age in 1989. A bimodal peak in incidence rates by age group was evident, with the first peak occurring between the ages of 15–29 years and a second peak occurring between the ages of 55–59 years [2]. Sonnenberg confirmed these findings, demonstrating a second peak of hospitalisations in European patients ≥60 years old [4]. Patients ≥60 years old account for 19% of patients with CD in the General Practice Research Database and 25% of hospitalisations in the USA [5, 6].

Clinical characteristics of CD patients may differ based on age at diagnosis. In a retrospective study, CD patients diagnosed over 40 years of age demonstrated higher rates of colonic involvement and non-complicated disease behaviour compared with younger patients [7]. French and Canadian cohort studies showed that CD patients 60 years and older were more likely to have colonic disease location [8, 9]. The development of CD complications (strictures or internal fistulas) has not been shown to be different in older patients compared with younger patients [8]; however, Ananthakrishnan et al. showed that elderly CD patients were less likely to be hospitalised with complicated disease [6].

The objective of our study was to compare complicated disease behaviour in CD patients based on age at diagnosis.

Methods

We compared differences in CD behaviour among patients diagnosed at <17 years), 17–40 years, 41–59 years and ≥60 years of age. We defined ‘elderly’ as those patients diagnosed at age ≥60 years. Disease behaviour was divided into the following categories: inflammatory, stricturing or penetrating according to the 2005 Montreal Classification system [10]. Patients with stricturing or penetrating disease were classified as complicated behaviour.

Design and setting

This was a cross-sectional study of adults with CD evaluated at the University of Maryland between July 2004 and April 2010. Demographics, family history of IBD, smoking history and extraintestinal manifestations are collected and updated at each visit.

Identification of participants

Adult patients with CD, confirmed in the record using standard clinical, endoscopic, radiographic and pathological criteria, were eligible to participate [11].

Formulation of CD phenotype

CD behaviour was categorised as inflammatory, stricturing and penetrating type, with or without perianal disease. Disease behaviour was determined based on the patients' entire medical history at the time of data extraction. Date of symptom onset was based on patient self-report and was confirmed by the medical provider at the initial visit.

Data analysis

We compared the unadjusted association between the study and outcome variables using the Chi-square test. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the likelihood of complicated behaviour in patients diagnosed at ≥60 years of age. Potential confounding variables were added to the model in stepwise fashion. Only those variables that were significant (P < 0.05) or that changed the odds ratio by ≥10% were included in the final model. All analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.2 (Cary, NC, USA).

This study was approved on 10 December 2009 by the University of Maryland IRB.

Results

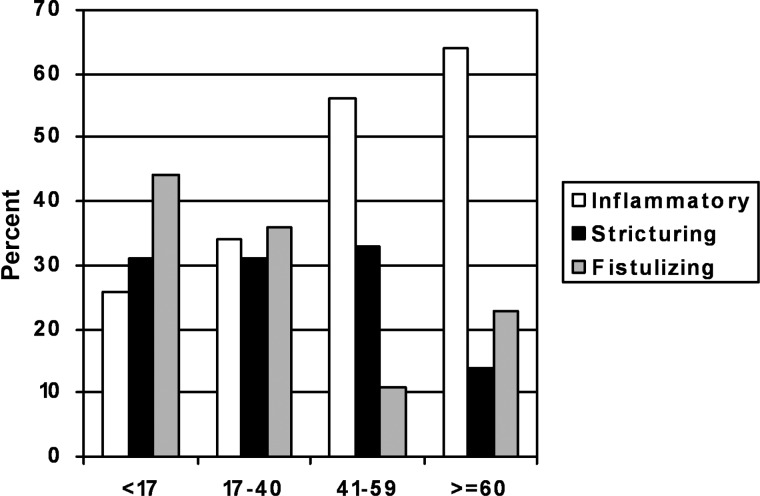

See Table 1 for the demographics of the 467 patients evaluated. Twenty two (5.0%) were diagnosed at ≥60 years. Of these, seven were diagnosed at ≥65 years, 3 at ≥70 years and 3 at ≥75 years of age. Two hundred and ninety-seven patients (64%) had complicated disease (see Figure 1). As age of diagnosis increased, the proportion of patients with complicated disease behaviour decreased. It can be seen that 74, 66, 44 and 36% of patients diagnosed <17, 17–40, 41–59 and 60 years of age and older had complicated disease, respectively (P < 0.01). When compared with persons <60 years, those ≥60 years had a significantly decreased odds of complicated disease (OR: 0.31, 95% CI: 0.13–0.75). The proportion of patients with colonic disease increased from 20% in patients <17 compared with 55% in patients ≥60 years (P < 0.01) (see Table 1). Adjustment for disease duration, disease location, perianal involvement and IBD family history revealed that the odds of having complicated disease when diagnosed at ≥60 years was 0.60 (95% CI: 0.21–1.65) (Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online), (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with Crohn's disease evaluated at the University of Maryland IBD Programme from July 2004 to April 2010 by age of diagnosis

| Variable | Overall (n = 467, n, %) | <17 years (n = 78; n, %) | 17–40 years (n = 312; n, %) | >40–59 years (n = 55; n, %) | ≥60 years (n = 22, n, %) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 191 (41) | 36 (46) | 129 (41) | 20 (36) | 6 (27) | 0.38 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 375 (80) | 22 (72) | 251 (80) | 48 (87) | 20 (91) | 0.07 |

| Family history | ||||||

| Yes | 130 (28) | 26 (33) | 94 (30) | 7 (13) | 3 (14) | 0.02 |

| Smoking history | ||||||

| Current | 111 (24) | 14 (18) | 78 (25) | 16 (29) | 3 (14) | 0.28 |

| Location | ||||||

| Ileal | 149 (34) | 15 (20) | 111 (38) | 19 (37) | 4 (20) | <0.01 |

| Colonic | 99 (23) | 15 (20) | 53 (18) | 20 (38) | 11 (55) | |

| Ileocolonic | 177 (42) | 44 (59) | 116 (40) | 13 (25) | 4 (20) | |

| Upper tractb | 63 (14) | 1 (1) | 9 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | |

| Behaviour | ||||||

| Inflammatory | 170 (36) | 20 (26) | 105 (34) | 31 (56) | 14 (64) | <0.01 |

| Stricturing | 141 (30) | 24 (31) | 96 (31) | 18 (33) | 3 (14) | |

| Penetrating | 156 (34) | 34 (43) | 111 (35) | 6 (11) | 5 (23) | |

| Perianalb | ||||||

| Yes | 149 (32) | 35 (45) | 101 (32) | 7 (13) | 6 (22) | <0.01 |

| Disease duration (mean years ± SD) | 13.7 ± 12.9 | 22.4 ± 10.1 | 13 ± 10.1 | 8.5 ± 7.7 | 5.5 ± 4.0 | <0.01 |

| Extraintestinal manifestation | ||||||

| Yes | 126 (27) | 21 (27) | 86 (28) | 15 (27) | 4 (18) | 0.82 |

SD, standard deviation.

aPearson Chi-square test.bUpper tract modifiers may co-exist with other location categories. Percentages reflect number of all patients with upper tract location.

Figure 1.

Crohn's disease behaviour of patients with Crohn's disease evaluated at the University of Maryland Inflammatory Bowel Disease program from July 2004 to April 2010 by age of diagnosis.

A subanalysis was performed to compare differences in disease behaviour between patients diagnosed at 41–59 years and those ≥60 years adjusting for disease location, demographics, family history of IBD, smoking and disease duration. There was no association between diagnosis at ≥60 years and complicated behaviour compared with those diagnosed between 41 and 59 years (OR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.15–2.36).

Table 2.

Association of age of diagnosis and stricturing or penetrating Crohn's disease behaviour adjusting for disease duration and location with logistic regression

| Variable | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | |

| ≥60 years | 0.56 (0.21–1.65) |

| <60 years | 1 (reference) |

| Disease duration from diagnosis | |

| <10 years | 0.44 (0.28–0.68) |

| ≥ 10 years | 1 (reference) |

| Disease location | |

| Colonic (isolated) | 0.15 (0.09– 0.25) |

| Other location | 1 (reference) |

| Perianal disease | |

| Yes | 1.70 (1.04–2.77) |

| No | 1 (reference) |

| Family history | |

| Yes | 0.69 (0.42–1.13) |

| No | 1 (reference) |

Discussion

Five percent of the patients were diagnosed at ≥60 years. Increasing age at diagnosis was associated with isolated colonic disease and non-complicated disease behaviour. Patients diagnosed at an older age had decreased duration of disease. After adjustment for confounding variables, the association with complicated disease behaviour was no longer significant.

Our findings are consistent with results published by Polito et al., where earlier age of diagnosis was associated with complicated disease; however, age at diagnosis was dichotomised at 40, making their older age diagnosis group younger than ours [7]. Our results are consistent with a study examining IBD-related hospitalisations in the USA in 2004 which demonstrated that elderly were less likely to have complicated disease [6]. Our results conflict with those of Gupta et al. and Freeman, which showed no difference in disease behaviour in older patients compared with younger patients [8, 12].

Our study found that 55% of patients diagnosed with CD ≥60 had isolated colonic disease. Polito et al. reported that 85% of patients diagnosed over 40 demonstrated colonic involvement; however, the number with isolated colonic disease was not reported. A retrospective study from British Columbia reported a higher rate of colonic involvement in elderly patients. Further, they used a standardised classification system to phenotype patients similar to the one used in our study [8, 13].

The propensity for colonic disease location and less severe disease phenotypes in older patients could be affected by colorectal cancer screening measures. It is possible that older patients are diagnosed when asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic during colorectal cancer screening. If this were true, we would expect older patients would have a decreased time between symptom onset and diagnosis. We compared the amount of time elapsed between symptom onset and time of diagnosis by age group. We found that time from symptom onset to diagnosis increased (data not shown) with increasing age. Therefore, it is unlikely that older patients are diagnosed at a pre-clinical stage with colonic disease location as a consequence of screening for colorectal cancer. It is also possible that elderly patients are less likely to undergo small bowel imaging and/or video capsule endoscopy for staging which would limit the detection of small bowel involvement. We did not collect information on the utilisation of small bowel imaging by age at diagnosis to evaluate for this potential bias.

Our study is limited by the small number of patients diagnosed at ≥60 years. Another limitation may be the fact that data on disease behaviour and location was taken at the time of data extraction. Since disease duration decreased significantly with age at diagnosis, it is possible that over time older patients will develop more complicated behaviour. Although speculative, this theory was supported by our regression analyses, which showed no association of age at diagnosis with complicated disease after adjustment for duration of disease. Finally, our patients were from a tertiary referral centre, making it possible that the proportion of patients with more complicated disease was overrepresented, impacting the generalisability of our results. To our knowledge, this is the first study analysing CD phenotypes using the Montreal classification system that separated the older age at the diagnosis cohort into two groups: 41–59 and ≥60 years. This study was strengthened by the use of adjusted analyses to control for disease duration and location, important confounding variables. We attempted to identify bias of the identification of pre-clinical colonic disease in older patients by examining the time from symptoms onset to diagnosis.

Our study suggests that patients diagnosed with CD ≥60 are more likely to exhibit isolated colonic disease location and less likely to have complicated disease, although the latter was not significant in the regression model. Our results should be interpreted with caution given the small sample size of patients diagnosed at ≥60 years. Given the lack of difference in disease behaviour or location seen between the two older age groups in our analysis, there may be little value in expanding on the current Montreal Classification system by isolating those diagnosed at ≥60. Larger studies are needed to examine disease location and behaviour in older CD patients. These studies should allow for adequate follow-up time for behaviour to ‘evolve’.

Key points.

Diagnosis of CD in older patients is uncommon.

Patients diagnosed at age 60 years and older are more likely to have isolated colonic disease than patients diagnosed at younger ages.

Patients diagnosed at age 60 years and older are less likely to develop complicated CD than patients diagnosed at younger ages.

The finding of less complicated disease in older patients may be confounded by differences in disease duration and disease location compared with younger patients.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

NIDDK T32 DK067872 Research Training in Gastroenterology.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text is available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

References

- 1.Loftus CG, Loftus EV, Jr, Harmsen WS, et al. Update on the incidence and prevalence of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940–2000. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:254–61. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lapidus A, Bernell O, Hellers G, Persson PG, Lofberg R. Incidence of Crohn's disease in Stockholm County 1955–1989. Gut. 1997;41:480–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.4.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cottone M, Cipolla C, Orlando A, Oliva L, Aiala R, Puleo A. Epidemiology of Crohn's disease in Sicily: a hospital incidence study from 1987 to 1989. “The Sicilian Study Group of Inflammatory Bowel Disease”. Eur J Epidemiol. 1991;7:636–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00218674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonnenberg A. Age distribution of IBD hospitalization. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:452–7. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Card T, Hubbard R, Logan RF. Mortality in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1583–90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Binion DG, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly is associated with worse outcomes: a national study of hospitalizations. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:182–89. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polito JM, II, Childs B, Mellits ED, Tokayer AZ, Harris ML, Bayless TM. Crohn's disease: influence of age at diagnosis on site and clinical type of disease. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:580–6. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8780560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman HJ. Crohn's disease initially diagnosed after age 60 years. Age Ageing. 2007;36:587–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heresbach D, Alexandre JL, Bretagne JF, et al. Crohn's disease in the over-60 age group: a population based study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:657–64. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000108337.41221.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lennard-Jones JE. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;170:2–6. doi: 10.3109/00365528909091339. discussion 16–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta S, Saverymuttu SH, Keshavarzian A, Hodgson HJ. Is the pattern of inflammatory bowel disease different in the elderly? Age Ageing. 1985;14:366–70. doi: 10.1093/ageing/14.6.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J, et al. A simple classification of Crohn's disease: report of the Working Party for the World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:8–15. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200002000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.