INTRODUCTION

Randomized controlled trials among patients with schizophrenia have shown that <20% improvement in the first two weeks of treatment predicts nonresponse after 12 weeks. The findings have been consistent for patients treated with both conventional (1) and second-generation antipsychotic (AP) drugs (2). However, despite the lack of evidence regarding the length of time that clinicians should pursue one treatment regimen, most psychiatric textbooks and practice guidelines suggest that patients should be treated for at least four to six weeks with one AP (3-5) before switching to another (6).

Large pragmatic trials with chronic patients, such as the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) (7), have found no benefit from switching AP drugs (8,9). No studies have considered less chronic patients, such as patients with recent-onset schizophrenia (i.e., less than five years of illness duration).

We investigated responses to APs and switching strategies in patients with recent-onset schizophrenia. We used the IPAP algorithm, which is a well-defined algorithm for treating schizophrenia (4,10).

METHODS

Study Design

The present study was a pilot, single-center, open, randomized trial. The trial was conducted in an outpatient setting at the Institute of Psychiatry (IPq) at the Hospital das Clínicas at the University of São Paulo Medical School, São Paulo/SP, Brazil. All of the subjects signed informed consent forms. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (protocol 0802/08) and was registered at Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01016145. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised in 1989). The subjects were randomized to receive either first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) or second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs). Once assigned to the FGA or SGA groups, the choice of drug within the class was left to the discretion of each treating psychiatrist. None of the included patients were regularly taking AP drugs upon entering the study.

The treatment followed the IPAP algorithm, which states that patients should be treated in monotherapy with either a first-generation (FGA) or second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) for at least two 4- to 6-week trials. The patients who failed to respond to these two trials were considered to be resistant to treatment and were eligible for clozapine.

The subjects were assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (11) at baseline and at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12.

The PANSS ratings were performed by three blinded and independent psychiatrists. The scale showed high reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.865).

Subjects

Patients between ages 18 and 45 years who met the DSM-IV TR criteria (12) for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders were included in the study. The patients had ≤5 years of illness and an exacerbation of symptoms with a minimum PANSS total score of 60 and a minimum Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S) score of 4.

The exclusion criteria were the presence of cognitive disorders of neurological etiology, a history of refractoriness to AP (i.e., previous or active use of clozapine), and active substance abuse.

Pharmacotherapy

The following APs were allowed in the study:

FGAs

haloperidol, 5-10 mg/day.

chlorpromazine, 25-800 mg/day

trifluoperazine, 5-10 mg/day

SGAs

olanzapine, 5-20 mg/day.

risperidone, 1-6 mg/day

quetiapine, 25 a 800 mg/day

ziprasidone, 80-160 mg/day

aripiprazole, 15-30 mg/day

Objectives

The primary aim of the study was to assess treatment resistance among patients with recent-onset schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. The study tested the hypothesis that no improvement in the PANSS score after two weeks of treatment was associated with nonresponse at 12 weeks. The secondary objectives were to evaluate the effectiveness of switching antipsychotic drugs after four weeks of treatment and to compare the response rate between the FGAs and SGAs.

Response definition

Response was defined as a ≥30% decrease in the PANSS score at any time in the study.

Improvement (in the first two weeks) was defined as a ≥20% decrease in the PANSS score.

Statistical analyses

The demographic and outcome variables (response/nonresponse) were compared between the groups using t-tests, Chi-squared test, and Fischer's exact tests. To compare the overall treatment effect over time, a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used; treatment was the between-group factor, and time was the within-subject factor. An analysis of covariance was performed to evaluate the treatment response at two weeks, and baseline PANSS was used as a covariate. The significance level was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Forty-nine subjects were screened for study eligibility, and 22 were included and randomized.

All of the patients had recent-onset schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and were not taking APs when they were included in the study. The baseline characteristics of all the participants are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics (n = 20).

| Characteristic | |

| Male/Female (n) | 10/10 |

| Paranoid schizophrenia (n) | 17 |

| Catatonic schizophrenia (n) | 1 |

| Schizoaffective disorder (n) | 2 |

| Age at screening (years, mean±SD) | 30.05±8.06 |

| Duration of untreated psychosis (years, mean±SD) | 1.65±2.66 |

| Illness duration (years, ±SD) | 3.25±3.14 |

| Total PANSS score (mean ±SD) | 94.16±21.99 |

| CGI severity (mean±SD) | 5.35±0.75 |

CGI: clinical global impression.

PANSS: positive and negative syndrome scale.

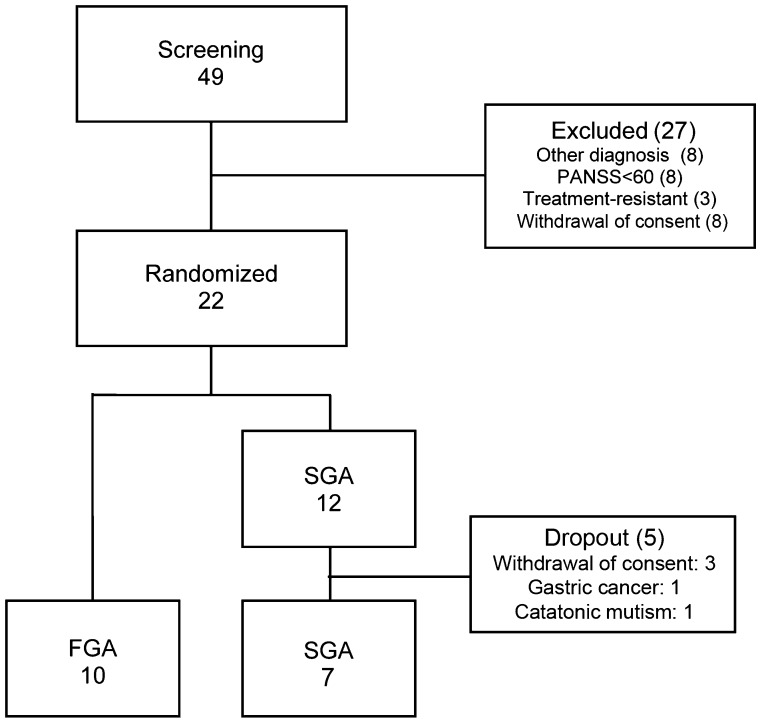

Twelve patients were randomized to receive SGAs, and 10 were randomized to receive FGAs (Figure 1). One patient withdrew consent after being randomized but before receiving treatment, and another patient could not be assessed because of catatonic mutism; therefore, we analyzed the baseline data from 20 patients (Table 1). Two patients withdrew from the study because they did not have a caregiver to transport them to the visits (n = 2), and one patient was excluded because of gastric cancer. All of the dropouts occurred in the SGA group before they had received treatment. Ultimately, the data from 17 patients were analyzed (7 SGA and 10 FGA patients).

Figure 1.

A patient allocation flow diagram. FGA: First-generation antipsychotic; SGA: second-generation antipsychotic.

After 12 weeks, 13 patients responded to treatment and 4 did not. The number of responders was similar in each group (FGA = 7, SGA = 6, p = 1.0). The mean PANSS reduction from baseline was also similar between the groups.

Independent sample t-tests demonstrated that the FGA and SGA groups were comparable in the patient demographic characteristics and treatment responses throughout the study. Because more than 50% of the patients switched their APs (7 from FGA and 5 from SGA), and there was no observable difference between the SGA and FGA groups, we conducted a pooled analysis of all the patients to assess the correlation between the 2-week improvements and 12-week responses.

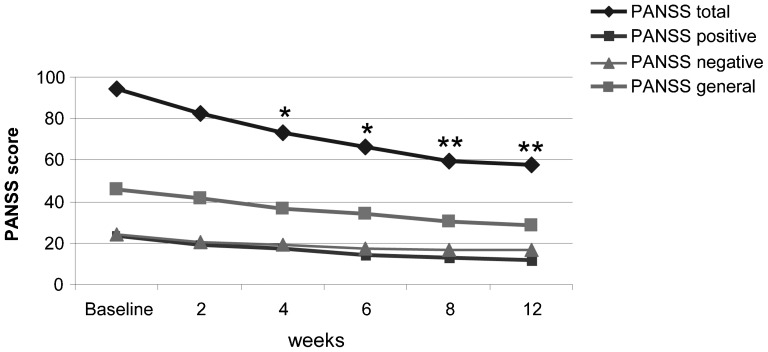

At 12 weeks, the mean PANSS change was 38.74%. This improvement corresponded to a mean decrease of 35 points (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PANSS – the mean change from baseline. PANSS: positive and negative syndrome scale, n = 17, *p<0.05 vs. baseline, **p<0.01 vs. baseline.

Repeated measures ANOVA showed the significant effect of time; there was an accumulated response rate over time. Five of the 13 responders showed no responses until 4 weeks. Pairwise comparisons between the baseline scores and weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 showed a significant change in the mean PANSS scores starting at week 4 (p<0.05).

A Chi-squared test between the lack of improvement at 2 weeks (at least 20% improvement in the PANSS score) showed no relationship to the 12-week nonresponse (χ2 = 0.60, df = 1, p = 0.57).

The subjects who failed to respond by the end of the study had lower baseline PANSS scores than the responders (79.25 vs. 91.23, p = 0.02); however, the ANCOVA analysis showed that a lack of improvement at two weeks failed to predict treatment nonresponse at 12 weeks (F = 1.907, p = 0.192).

Twelve of the 20 patients switched APs. One patient switched from an SGA to an FGA after experiencing an allergic reaction to a single dose of risperidone. The other AP switches occurred because of a lack of efficacy. In the patients who switched, 75% responded by the end of the study, but this rate was not significant when compared to the patients who did not switch (p = 1.00).

DISCUSSION

We found that lack of improvement in the first two weeks does not predict nonresponse at 12 weeks. Even the patients who did not exhibit a minimal PANSS improvement of 20% at two weeks had responded by 12 weeks. Previous reports have shown that early nonresponse was predictive of refractoriness; however, such analyses were based on patients with chronic and possibly already refractory schizophrenia (1,2).

As observed in chronic patients (8,9), switching APs was of little benefit in our study. However, the small sample size limits the generalizability of our findings.

Physicians tend to switch antipsychotics for different reasons. Physicians are willing to wait longer for some drugs than for others because the onset of efficacy is not exact for all antipsychotics (e.g., risperidone acts faster than olanzapine) (13).

D2/3 receptors are occupied by the AP in a few hours, but the clinical response may not occur for weeks (14,15); this delayed onset of a clinical response can be explained by the fact that a stable blockade of those receptors may be necessary before a sustained clinical effect is observed (15).

Because this is a pilot study with a small sample of recent-onset patients, caution is needed in interpreting the results. Our study found that lack of improvement in the first two weeks does not predict treatment resistance in recent-onset psychosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank nursing staff members Norma Aparecida da Silva and Luis Antonio da Silva for their kind collaboration in collecting samples and biometrics. The authors declare no conflicts of interest and have received no outside funding.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Correll CU, Malhotra AK, Kaushik S, McMeniman M, Kane JM. Early prediction of antipsychotic response in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(11):2063–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinon BJ, Chen L, Ascher-Svanum H, Stauffer VL, Kollack-Walker S, Zhou W, et al. Early response to antipsychotic drug therapy as a clinical marker of subsequent response in the treatment of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(2):581–90. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, Noel JM, Boggs DL, Fischer BA, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):71–93. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elkis H. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(3):511–33. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, McGlashan TH, Miller AL, Perkins DO, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2 Suppl) :1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki T, Uchida H, Watanabe K, Nomura K, Takeuchi H, Tomita M, et al. How effective is it to sequentially switch among Olanzapine, Quetiapine and Risperidone. A randomized, open-label study of algorithm-based antipsychotic treatment to patients with symptomatic schizophrenia in the real-world clinical setting. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;195(2):285–95. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0872-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005 22. 353(12):1209–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Essock SM, Covell NH, Davis SM, Stroup TS, Rosenheck RA, Lieberman JA. Effectiveness of switching antipsychotic medications. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2090–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Xu W, Thomas J, Henderson W, Frisman L, et al. A comparison of clozapine and haloperidol in hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;337(12):809–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709183371202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elkis H, Meltzer HY.[Refractory schizophrenia] Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 200729 Suppl 2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edition ed. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatta K, Sato K, Hamakawa H, Takebayashi H, Kimura N, Ochi S, et al. Effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics with acute-phase schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapur S, Agid O, Mizrahi R, Li M. How antipsychotics work-from receptors to reality. NeuroRx. 2006;3(1):10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.nurx.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pani L, Pira L, Marchese G. Antipsychotic efficacy: relationship to optimal D2-receptor occupancy. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(5):267–75. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]