Abstract

MCs (mast cells) adversely affect atherosclerosis by promoting the progression of lesions and plaque destabilization. MC chymase cleaves apoA-I (apolipoprotein A-I), the main protein component of HDL (high-density lipoprotein). We previously showed that C-terminally truncated apoA-I (cleaved at the carboxyl side of Phe225) is present in normal human serum using a newly developed specific mAb (monoclonal antibody). In the present study, we aimed to identify chymase-induced cleavage sites in both lipid-free and lipid-bound (HDL3) forms of apoA-I. Lipid-free apoA-I was preferentially digested by chymase, at the C-terminus rather than the N-terminus. Phe229 and Tyr192 residues were the main cleavage sites. Interestingly, the Phe225 residue was a minor cleavage site. In contrast, the same concentration of chymase failed to digest apoA-I in HDL3; however, a 100-fold higher concentration of chymase modestly digested apoA-I in HDL3 at only the N-terminus, especially at Phe33. CPA (carboxypeptidase A) is another MC protease, co-localized with chymase in severe atherosclerotic lesions. CPA, in vitro, further cleaved C-terminal Phe225 and Phe229 residues newly exposed by chymase, but did not cleave Tyr192. These results indicate that several forms of C-terminally and N-terminally truncated apoA-I could exist in the circulation. They may be useful as new biomarkers to assess the risk of CVD (cardiovascular disease).

Keywords: carboxypeptidase A, cardiovascular disease, chymase, mass spectrometry, mast cell, truncated apolipoprotein A-I

Abbreviations: Ang I, angiotensin I; 2-DE, two-dimensional gel-electrophoresis; apoA-I, apolipoprotein A-I; BTEE, benzoyl-L-tyrosine ethyl ester; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCL/MS, chemical cross-linking/MS; CPA, carboxypeptidase A; CVD, cardiovascular disease; H&E, haematoxylin and eosin; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IEF, isoelectric focusing; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MC, mast cell; pI, isoelectric points; POD, peroxidase; TCA, trichloroacetic acid; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; MALDI–TOF-MS, matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization–time-of-flight MS; WB, Western blotting

INTRODUCTION

MCs (mast cells) distribute to mucosal surfaces and skin throughout the body and play an important role in the first line of defence against pathogens. When activated, MCs release granules containing many mediators such as histamine, proteases, cytokines and chemokines [1]. The number and the rate of activated MCs in atherosclerotic lesions increase with the progression of the disease [2], and MC-derived mediators are directly related to the development and progression of atherosclerosis [3]. Especially, MC-neutral proteases, tryptase and chymase, induce degradation of the extracellular matrix and apoptosis of macrophages and arterial wall cells, such as endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells, resulting in plaque destabilization and rupture.

The levels of MC mediators in the circulation have been screened as predictors of CVD (cardiovascular disease). Deliargyris et al. [4] reported that serum tryptase levels in patients with CAD (coronary artery disease), with at least 50% stenosis in one or more arteries, were significantly higher than those in patients with non-significant CAD. Consistent with this finding, Xiang et al. [5] reported that patients with AMI (acute myocardial infarction) have 2-fold higher tryptase levels than those with unsubstantial coronary heart disease. Serum chymase levels show the same tendency as tryptase levels with no statistically significant difference. In contrast, Kervinen et al. [6] reported no difference in tryptase levels between patients with acute coronary syndrome and controls. Thus, the practicability of MC mediators as biomarkers for CAD remains uncertain.

Chymase, in vitro, cleaves apoA-I (apolipoprotein A-I) in reconstituted HDL (high-density lipoprotein) at the N-terminus (carboxyl side of Tyr18 or Phe33) or C-terminus (carboxyl side of Phe225) [7]. We hypothesized that apoA-I fragments could be potential biomarkers of CAD because the production of apoA-I fragments is considered to reflect focal MC activation in atherogenic plaques. Recently, we generated a specific mAb (monoclonal antibody; 16-4 mAb) that recognizes C-terminally truncated apoA-I (cleaved at the carboxyl side of Phe225) but not intact apoA-I, and we demonstrated the presence of extremely small amounts of C-terminally truncated apoA-I in normal human serum [8]. We also attempted to develop a quantitative method to measure C-terminally truncated apoA-I in serum using 16-4 mAb; however, the sensitivity was not sufficient to detect the presumably low content. On the other hand, only a fraction of the 26 kDa fragment produced by chymase digestion in vitro reacted with 16-4 mAb. These results led us to speculate that truncated apoA-I cleaved at the carboxyl side of Phe225 is not the predominant apoA-I fragment produced by chymase proteolysis and/or is immediately catalysed by different proteases.

MCs package another specific protease, MC-CPA (carboxypeptidase A), in secretory granules. MC-CPA cleaves hydrophobic C-terminal residues [9]. Because chymase and MC-CPA reside in MCs granules in complexes with proteoglycan, which are distinct from complexes that include tryptase [10], chymase and MC-CPA probably co-localize in the extracellular matrix after degranulation. Chymase and MC-CPA act cooperatively as follows: chymase cleaves a protein at the carboxyl side of aromatic amino acids, producing a new C-terminal residue that is further digested by MC-CPA. In vivo, chymase and MC-CPA cooperatively cleave Ang I (angiotensin I), contributing to the formation and degradation of Ang II, respectively [11].

A quantitative analysis of apoA-I fragments induced by chymase and/or MC-CPA could be a useful way to estimate the progression of atherogenic lesions. However, apoA-I fragment profiles remain to be defined. In this study, we characterized apoA-I fragments produced by chymase digestion of lipid-free apoA-I and HDL3 using 2-DE (two-dimensional gel-electrophoresis) and MS. We also examined the possibility that MC-CPA further digests apoA-I fragments produced by chymase cleavage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Blood samples

Blood samples were obtained from healthy volunteers who had provided informed consent. The study was approved by our institutional research ethics committee [No. 614].

Isolation of HDL and purification of apoA-I

Whole HDL (1.063–1.21 g/ml) and HDL3 (1.125–1.21 g/ml) were isolated from pooled serum by ultracentrifugation [12]. Lipid-free apoA-I was purified from whole HDL using a method reported previously [8]. Isolated HDL3 and lipid-free apoA-I were dialysed against 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl and 10 mM CaCl2, and they were stored at 4 °C and −20 °C, respectively, until further use.

Chymase and CPA digestion

Lipid-free apoA-I and HDL3 were incubated with human skin MC chymase (Elastin Products Company) and recombinant human CPA4 (R&D Systems) in 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl and 10 mM CaCl2 at 37 °C.

Western blotting

Chymase-digested apoA-I fragments were analysed by SDS/PAGE and 2-DE. SDS/PAGE was performed using a 12.5% polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions. IEF (isoelectric focusing) was used as the first dimension of 2-DE, with 4% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels containing 8 M urea and 5% Pharmalyte, pH 4.0–6.5 (GE Healthcare). After alkylation and reduction of the IEF gel, SDS/PAGE was used as the second dimension. WB (Western blotting) was performed as previously described [8]. Briefly, proteins separated by electrophoresis were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). ApoA-I and apoA-I fragments were detected with goat anti-apoA-I polyclonal antibody (Academy Bio-Medical Company) and POD (peroxidase)-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG (Medical & Biological Laboratories). C-terminally truncated apoA-I (truncated at the carboxyl side of Phe225), if any, was detected with 16-4 mAb and POD-conjugated goat anti-mouse μ-chain antibody (SouthernBiotech). Finally, bands and spots containing apoA-I and its fragments were visualized with 3,3′-DAB (diaminobenzidine)-4HCl and H2O2.

MALDI–TOF-MS (matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization–time-of-flight MS) analysis

A portion (10 μl) of chymase- and/or CPA-treated lipid-free apoA-I (~1 mg/ml) was desalted using ZipTip C18 (Millipore) and eluted with 10 μl of 80% (v/v) acetonitrile/0.1% TFA (trifluoroacetic acid). Chymase- and/or CPA-treated HDL3 was similarly desalted and delipidated as follows. Thirty microlitres of digested sample was mixed with an equal volume of 20% (w/v) TCA (trichloroacetic acid)/acetone. After addition of 150 μl of ice-cold acetone, the mixture was centrifuged at 17000 g and 4 °C for 15 min. The pellet was washed three times with 100 μl of ice-cold diethyl ether to remove TCA and was dissolved in 30 μl of 0.1% TFA. Both solutions obtained from lipid-free apoA-I and HDL3 were mixed with 3 mg/ml sinapinic acid in 50% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA and applied to a μFocus MALDI plate (Hudson Surface Technology). MS analysis was conducted using an UltrafleXtreme (Bruker Daltonics) using positive ion mode. Calibration was carried out using a Protein Standard II (Bruker Daltonics) containing trypsinogen, Protein A and bovine albumin. Mass data were analysed by flexAnalysis (Bruker Daltonics) and ProteinProspector (http://prospector.ucsf.edu/prospector/mshome.htm).

HPLC–MALDI-MS analysis

Nano-HPLC was performed with an EASY-nLC II (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a one-column set-up (without a trap column). The fraction collector was a PROTEINEER fc II (Bruker Daltonics). The TOF-MS was an UltrafleXtreme (Bruker Daltonics). The purities of all chemicals were of HPLC-MS or HPLC grade. The nano-HPLC column was a MonoCap C18 Fast-flow (0.075 mm i.d.×100 mm, GL Sciences). The eluents used were aqueous 0.1% TFA as eluent A and acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA as eluent B. The gradient programme started at 100% of eluent A and increased to 40% of eluent B in 5 min as the first step, then increased to 70% of eluent B in 15 min as the second step. The total flow rate was 400 nl/min. A portion (10 μl) of the protein sample (0.2 mg/ml) was injected into the nano-HPLC column. The eluate was fractionated on the sample plate of the TOF mass spectrometer at 20 s intervals. Super DHB (Bruker Daltonics) was used as the MALDI matrix. Mass spectra for molecular mass determination were obtained by linear TOF mode. For top-down amino acid sequence analysis, the in-source decay mass spectra of proteins were obtained by reflectron TOF mode.

Immunohistochemical analysis

To analyse the co-localization of chymase and CPA in atherosclerotic lesions, the aortic arch region was serially sectioned in 3-μm sections and stained with anti-chymase antibody (Genetex) and anti-CPA3 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich Japan) in addition to H&E (haematoxylin and eosin). The signal was visualized with EnVision+System-HRP Labelled Polymer (Dako Japan, Kyoto, Japan) as the secondary antibody.

RESULTS

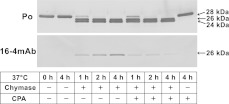

Degradation of lipid-free apoA-I and HDL3 by chymase

Lipid-free apoA-I (1 mg/ml) and HDL3 (1 mg protein/ml) were incubated with 0.03 and 3.0 BTEE (benzoyl-L-tyrosine ethyl ester) unit/ml of chymase at 37 °C, respectively, and the degradation profiles were analysed by SDS/PAGE followed by WB using anti-apoA-I and 16-4 mAb antibodies (Figure 1). As previously reported, digestion of apoA-I produced fragments with apparent molecular masses of 26 and 24 kDa that reacted with anti-apoA-I antibody. The 26 kDa fragment was also partially detected by 16-4 mAb antibody (Figure 1A). Although digestion of HDL3 also produced two fragments, as with lipid-free apoA-I, the intensity of the 26 kDa fragment was much lower than the intensity of the 24 kDa fragment (Figure 1B). In addition, 16-4 mAb antibody did not recognize the 26 kDa fragment. Incidentally, no degradation of HDL3 was observed with 0.03 BTEE unit/ml of chymase (results not shown). These results indicate that chymase-susceptibility and the chymase-susceptible sites differ in lipid-free apoA-I and in apoA-I with HDL3 as a component.

Figure 1. Truncation of lipid-free apoA-I and apoA-I in HDL3 by chymase digestion.

Lipid-free apoA-I (A) and HDL3 (B) were treated with (+) or without (−) chymase (0.03 BTEE unit/ml for lipid-free apoA-I and 3.0 BTEE unit/ml for HDL3) for the indicated times (min). The digested mixtures were analysed by SDS/PAGE followed by WB using anti-apoA-I antibody (Po) and 16-4 mAb, which specifically reacts with truncated apoA-I at the carboxyl side of Phe225 [8].

MALDI–TOF-MS analysis and top-down sequencing

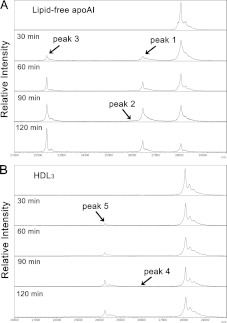

Digested apoA-I fragments were assessed in detail using MALDI–TOF-MS. Chymase digestion of lipid-free apoA-I produced three novel peaks at m/z 26454 (peak 1), 25964 (peak 2) and 22374 (peak 3) (Figure 2A). Peaks 1 and 2 and peak 3 might correspond to the bands with apparent molecular masses of 26 kDa and 24 kDa, respectively, in SDS/PAGE. The fragments in each peak were partially purified by HPLC, and their terminal sequences were determined using top-down sequencing analysis by MALDI–TOF-MS. Although the sequence signals of the C-terminus was not detected, the N-terminal sequence (Asp1–Leu47) of the fragment in peak 3 was the same as the N-terminal sequence of intact apoA-I (results not shown), indicating that peak 3 corresponded to C-terminally truncated apoA-I cleaved at the carboxyl side of Tyr192 [Δ(193–243)apoA-I]. In contrast, no terminal sequences were obtained from the fragments in peaks 1 and 2. However, the m/z of peak 1, 26454, corresponded to the molecular mass of truncated apoA-I cleaved at the carboxyl side of Phe229 (Δ(230–243)apoA-I). Similarly, peak 2, m/z 25964, corresponded to Phe225 [Δ(226–243)apoA-I] and/or Tyr18 [Δ(1–18)apoA-I].

Figure 2. MALDI–TOF-MS analysis of chymase-digested lipid-free apoA-I and HDL3.

Lipid-free apoA-I (A) and HDL3 (B) digested with chymase for 0–120 min, as shown in Figure 1, were analysed by MALDI–TOF-MS over a m/z range from approximately 20000 to 30000.

On the other hand, two peaks were detected at m/z 25980 (peak 4) and 24271 (peak 5) by MS analysis of chymase-digested HDL3 (Figure 2B). Peak 4 was very weak to be purified and analysed by top-down sequencing. However, both the N-terminal (Glu34–Asn74) and the C-terminal (Tyr192–Gln243) sequences of the fragment in peak 5 were successfully detected by top-down sequencing and were shown to be identical to those of apoA-I cleaved at the carboxyl side of Phe33 [Δ(1-33)apoA-I] (results not shown).

2-DE of the chymase-digested fragments

For further qualitative and quantitative analysis of apoA-I fragments, chymase-digested lipid-free apoA-I and HDL3 were isolated by 2-DE and visualized by WB. Two major apoA-I spots with an apparent molecular mass of 28 kDa were observed on blots of both lipid-free and HDL3-bound apoA-I without chymase digestion (Figures 3A and 3B upper panels). The spot of intact apoA-I with the lower pI (isoelectric points) might also be a deamidated form [13]. When lipid-free apoA-I was digested by chymase for 2 h, several new spots were detected (Figure 3A, lower panel). As well as intact apoA-I, spots 2 and 5 might be deamidated forms of spots 1 and 4, respectively. Only spots 2 and 3 (might be deamidated form of spot 2) were recognized by 16-4 mAb (results not shown), indicating that spot 2 included both the deamidated form of spot 1 and Δ(226–243)apoA-I, which was a minor fragment. The pI of intact apoA-I, Δ(230–243)apoA-I, Δ(193–243)apoA-I, Δ(1–18)apoA-I and Δ(226–243)apoA-I, calculated from the amino acid sequences, are 5.27, 5.25, 5.04, 5.45 and 5.17, respectively. Spots 1 and 2 corresponded to peak 1 [Δ(230–243)apoA-I] because of apparent molecular mass and similar pI to intact apoA-I on 2-DE. Spots 4 and 5 might be Δ(193–243)apoA-I because of those extremely low pI, although a significant difference was observed between molecular masses obtained from MS analysis and SDS/PAGE. Spot 6 was identified as Δ(1–18)apoA-I, since its molecular mass was similar to those of spots 1 and 2 and its pI was more alkaline than that of intact apoA-I. In conclusion, chymase digestion of lipid-free apoA-I produced at least four forms of truncated apoA-I: Δ(230–243)apoA-I, Δ(226–243)apoA-I, Δ(193–243)apoA-I and Δ(1–18)apoA-I, among which the main fragments were Δ(230–243)apoA-I and Δ(193–243)apoA-I.

Figure 3. 2-DE of chymase-digested lipid-free apoA-I and HDL3.

Lipid-free apoA-I (A) and HDL3 (B) were analysed by 2-DE after incubation for 2 h with (+) or without (−) chymase as shown in Figure 1. The apoA-I spots visualized using anti-apoA-I antibody were given numbers to make the descriptions in the text easy to understand.

On the other hand, only two spots (7 and 8) were detected in chymase-digested HDL3 (Figure 3B, lower panel), and no spots were detected using 16-4 mAb (results not shown). As described above, spot 8 seems to be deamidated form of spots 7. Spot 7 was identified as Δ(1-33)apoA-I because of its extremely high pI (the calculated pI of Δ(1-33)apoA-I is 5.56), its apparent molecular mass, and the results obtained from MALDI–TOF-MS analysis of chymase-digested HDL3 (peak 5 in Figure 2B). No spot corresponding to peak 4 in Figure 2(B) was observed.

The relationships among the peaks in MALDI–TOF-MS analysis, the spots in 2-DE and the bands in SDS/PAGE, including calculated molecular mass (Da) and pI, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of chymase-digested truncated apoA-I.

| Peak* | m/z† | N-terminal‡ | tapoA-I§ | Mass∥ | PAGE¶ | pI∥ | 2-DE** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid-free apoA-I | |||||||

| Intact apoA-I | 28076 | 1- | 28080 | 28 kDa | 5.27 | ||

| Peak 1 | 26454 | − | Δ(230–243) | 26441 | 26 kDa | 5.25 | Spot 1, 2 |

| Peak 2 | 25964 | − | Δ(226–243) | 25980 | 26 kDa | 5.17 | Spot 2, 3 |

| 25964 | − | Δ(1–18) | 25982 | 26 kDa | 5.45 | Spot 6 | |

| Peak 3 | 22374 | 1- | Δ(193–243) | 22368 | 24 kDa | 5.04 | Spot 4, 5 |

| HDL3 | |||||||

| Intact apoA-I | 28079 | − | 28080 | 28 kDa | 5.27 | ||

| Peak 4 | 25980 | − | Δ(1–18) | 25982 | 26 kDa | 5.45 | – |

| Peak 5 | 24271 | 34- | Δ(1–33) | 24272 | 24 kDa | 5.56 | Spot 7, 8 |

*Peak number detected by MALDI–TOF-MS.

†Representative m/z obtained from MALDI–TOF-MS.

‡Detected N-terminal sequence by top-down sequencing.

§Estimated truncated apoA-I.

∥Calculated molecular mass and pI of tapoA-I.

¶Apparent molecular mass obtained from SDS/PAGE.

**Corresponding spot number on 2-DE pattern.

Immunohistochemical identification of chymase and CPA

To assess the presence of chymase and MC-CPA in advanced atherosclerotic lesions, serial sections, with severe atherosclerosis confirmed by H&E staining, were immunologically stained using anti-chymase and anti-CPA antibodies. Co-localization of chymase and CPA was observed in the intimal area of severe atherosclerotic lesions, with extensive degranulation of MCs (Figure 4). In contrast, in specimens with non-atherosclerotic lesions, chymase and CPA were observed in the medial to adventitial area, in MCs without evidence of degranulation, but almost no staining was observed in the intimal area (results not shown).

Figure 4. Representative sections of atherosclerotic lesions stained with H&E (A and B) and anti-chymase (C) and anti-CPA (D) antibodies.

Severe atherosclerotic lesions were confirmed by H&E staining (A). The rectangle bounded by black line indicates the areas magnified in (B), (C) and (D). ‘Ad’ and ‘In’ refer to adventitial and intimal sides, respectively. Black arrows indicate the co-localization of chymase and CPA with extensive degranulation of MCs.

Simultaneous digestion of apoA-I by chymase and CPA

To determine whether CPA further cleaves chymase-digested products, 1 mg/ml of lipid-free apoA-I was simultaneously treated with 0.05 BTEE unit/ml of chymase and 5 μg/ml of CPA for 4 h, and analysed by WB and MALDI–TOF-MS. No apparent difference between the treatment with only chymase and that with chymase and CPA was observed in the WB patterns using the polyclonal anti-apoA-I antibody (Figure 5). The band intensity of chymase-digested Δ(226–243)apoA-I, visualized by 16-4 mAb, increased in a time-dependent manner. However, the intensity of Δ(226–243)apoA-I in the treatment with both chymase and CPA increased slightly and then decreased during 4 h.

Figure 5. Simultaneous digestion of apoA-I by chymase and CPA.

Lipid-free apoA-I was simultaneously digested by 0.05 BTEE unit/ml of chymase and 5 μg/ml of CPA for 0–4 h and analysed by SDS/PAGE followed by WB using anti-apoA-I antibody (Po) and 16-4 mAb. Lipid-free apoA-I digested by only chymase and non-digested lipid-free apoA-I were also analysed as controls.

Lipid-free apoA-I treated with chymase and chymase/CPA for 4 h were also analysed by MALDI–TOF-MS. Two groups of peaks with m/z of approximately 26454 and 22386 were obtained (Figure 6A) and analysed in greater detail (Figures 6B and 6C). The main peaks with m/z 26454 (peak 1) and 25991 (peak 2), corresponding to Δ(230–243)apoA-I and Δ(226–243)apoA-I, respectively, obtained by digestion with chymase were decreased by additional treatment with CPA. Two new peaks with m/z 26308 and 25834, which were approximately 150 Da smaller than peaks 1 and 2, respectively, appeared upon additional treatment with CPA (Figure 6B). The peak with m/z 22386 (peak 3), corresponding to Δ(193–243)apoA-I, showed no change after the additional CPA treatment (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. MALDI–TOF-MS analysis of lipid-free apoA-I simultaneously digested by chymase and CPA.

Lipid-free apoA-I treated with chymase (grey lines) and chymase/CPA (black lines) for 4 h, as shown in Figure 5, was analysed by MALDI–TOF-MS. The wide-range (from m/z approximately 20000–30000) profile (A) shows two groups of peaks. The small (B) and large (C) rectangles bounded by grey lines indicate areas enlarged in (B) and (C), respectively. Numbers in the Figures indicate m/z.

DISCUSSION

Chymase preferentially cleaved apoA-I at different domains in the lipid-free and lipid-bound forms. The lipid-free form was mainly digested at the C-terminus rather than the N-terminus, especially at Phe229 and Tyr192. In contrast, the lipid-bound form (HDL3), with a relatively higher resistance to cleavage, was digested in the N-terminus, especially at Phe33. Considering the three-dimensional structure of lipid-free apoA-I [14], both CCL/MS (chemical cross-linking/MS) [15] and X-ray analysis [16] essentially provide similar insight: lipid-free apoA-I consists of four N-terminal (amino acids 1–187) and 2 C-terminal (amino acids 188-243) α-helix bundles. However, the in-solution conformation obtained by CCL/MS seems to be less organized and more flexible than the crystal structure obtained from the X-ray analysis. The N-terminal domain constructs a stable antiparallel helix-bundle though the formation of a hydrophobic core by all four N-terminal helices. Because aromatic amino acid residues, which are preferentially cleaved by chymase, face towards the core, it may be difficult for chymase to access the N-terminus of lipid-free apoA-I. In contrast, the C-terminal domain is less organized than the N-terminus. Tyr192 is located in a loop between the N-terminal and C-terminal domains which is solvent accessible. These conformational features lead us to postulate that Tyr192 is a likely candidate for sites cleaved by chymase. These insights do not contradict our results, in which chymase-digestion of lipid-free apoA-I produced mainly C-terminally truncated forms of apoA-I, such as Δ(230–243)apoA-I, Δ(226–243)apoA-I, and Δ(193–243)apoA-I, and only a small amount of N-terminally truncated apoA-I, Δ(1–18)apoA-I, was detected. There are two phenylalanines (Phe225 and Phe229) and one tyrosine (Tyr236) residue in the C-terminal helix. Although it is not known why Phe229, of these three residues, is the most susceptible to chymase cleavage, the secondary and/or tertiary structure, such as charge and hydrophobicity of neighbouring residues, could influence cleavage susceptibility.

The low concentration of chymase (0.03 BTEE units/ml) that readily digested lipid-free apoA-I failed to digest lipid-bound apoA-I (apoA-I in HDL3). ApoA-I in HDL3 was barely digested at one site in the N-terminus, on the carboxyl side of Phe33, with 3.0 BTEE unit/ml of chymase, a concentration 100-fold higher than that used for digestion of lipid-free apoA-I. C-terminal helices are the most hydrophobic regions in apoA-I [17] and are important for lipid binding [18,19]. Kono et al. [19] proposed a two-step mechanism for the binding of human apoA-I to a lipid particle surface. The C-terminal hydrophobic domain initially binds to a lipid particle surface, causing the four-helical bundle in the N-terminus to open. Consequently, hydrophobic helix–helix interactions in the N-terminal bundle convert to helix–lipid interactions. They also speculated that the conformational conversion of the N-terminal bundle is controlled by the apoA-I surface concentration and the cholesterol content of lipoprotein particles, such as HDL3 [18]. This is probably one reason why the N-terminal domain is relatively more susceptible to chymase than the C-terminal domain. However, the chymase susceptibility of the N-terminus in lipid-bound apoA-I is extremely low compared with that of the N-terminus in lipid-free apoA-I.

Lee et al. [7] reported that reconstituted HDL particles containing apoA-I were cleaved either at the N-terminus (Tyr18 or Phe33) or the C-terminus (Phe225). In contrast, the cleavage site identified in the present study was on the carboxyl side of Phe33 in HDL3-bound apoA-I. The different results may be due to the differences in the type of lipid-bound apoA-I used, between reconstituted HDL and isolated HDL3, and in the type of chymase used. In the present study, we used purified human skin MC chymase for HDL3 digestion. However, Lee et al. [7] used both recombinant human chymase and rat chymase (MC granule remnants). On the basis of previous histochemical observations [20,21], Lindstedt et al. [22] estimated that the chymase concentration in the intimal fluid is 0.6 μg/ml. However, the concentration would be higher in the shoulder region of atheromas [2]. In the present study, to digest apoA-I in HDL3 we used 3.0 BTEE units/ml, corresponding to approximately 17 μg/ml chymase, a concentration considerably higher than the physiological level in atherosclerotic lesions. This suggests that it may be difficult for chymase in atherosclerotic lesions to digest apoA-I in HDL3 particles at Phe225, indicating that C-terminally truncated apoA-I (cleaved at Phe225), recently identified by us in normal human serum [8], derives from chymase-digested lipid-free apoA-I and/or lipid-poor apoA-I.

Although no spot with a molecular mass of approximately 26 kDa was observed in the 2-DE pattern for chymase-digested HDL3 (Figure 3B), we detected an extremely small amount of this fraction as a faint 26 kDa band in the SDS/PAGE pattern (Figure 1B) and as peak 4 at m/z 25980 in MALDI–TOF-MS analysis (Figure 2B). Peak 4 was considered to correspond to Δ(226–243)apoA-I and/or Δ(1–18)apoA-I. Consequently, this minor fraction could consist of Δ(1–18)apoA-I but not Δ(226–243)apoA-I because lipids might block the C-terminal region of apoA-I from the attack of chymase.

One of the two types of MCs, MCTC, which contains both tryptase and chymase, also carries CPA [23]. CPA appears to work cooperatively with chymase in atherosclerotic lesions. In histochemical experiments, CPA co-localized with chymase within the aspect of an extensive degranulation in severe atherosclerotic lesions. CPA cleaved, in vitro, C-terminal Phe225 and Phe229 residues newly exposed by chymase digestion of lipid-free apoA-I and produced new forms of C-terminally truncated apoA-I, cleaved at the carboxyl sides of Ser224, Δ(225–243)apoA-I, and Ser228, Δ(229–243)apoA-I, respectively. The decrease of approximately 150 Da in MALDI–TOF-MS analysis of lipid-free apoA-I after additional digestion with CPA reflects the deletion of a phenylalanine residue. Further investigation is needed to clarify the presence of Δ(225–243)apoA-I and Δ(229–243)apoA-I in human serum. However, the concentrations of Δ(225–243)apoA-I and Δ(229–243)apoA-I in the circulation might be lower than that of Δ(226–243)apoA-I and Δ(230–243)apoA-I, respectively.

Activated MCs play an important role in the progression of atherosclerotic lesions and in plaque destabilization and rupture [3]. Many kinds of mediators released by MCs, which are known biomarkers for inflammation [24], might also be biomarkers for atherosclerotic disease. However, they might not detect atherosclerosis with high specificity. In contrast, truncated apoA-I(s) would be produced only at local atherosclerotic lesions where a large number of MCs are activated. Truncated apoA-I would have reduced ability to bind lipids and would be easily catabolized through the kidney. However, even the minor fraction of chymase-digested fragments, Δ(226–243)apoA-I, was identified in normal human serum, as described previously [8]. Therefore other truncated apoA-Is, such as Δ(193–243)apoA-I and Δ(230–243)apoA-I, might exist in the circulation. This suggests that quantification of truncated apoA-I might be a useful way to estimate risk for CVD.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Takeshi Kasama and Minoru Tozuka designed and supervised the study. Yoko Usami, Yukihiro Kobayashi, Takahiro Kameda, Akari Miyazaki and Yuriko Kurihara carried out research. Kazuyuki Matsuda, Kenji Kawasaki and Mitsutoshi Sugano were consultants for the laboratory methods. Yoko Usami, Kazuyuki Matsuda, Mitsutoshi Sugano, Takeshi Kasama and M. Tozuka analysed data. Yoko Usami and Minoru Tozuka wrote the paper, and Takeshi Kasama and Yukihiro Kobayashi commented on drafts of the paper.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Professor Takayuki Honda and Dr Kenji Sano (Department of Laboratory Medicine, Shinshu University) for their assistance.

FUNDING

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science [grant number 21590611].

References

- 1.Pejler G., Abrink M., Ringvall M., Wernersson S. Mast cell proteases. Adv. Immunol. 2007;95:167–255. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(07)95006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaartinen M., Penttilä A., Kovanen P. T. Accumulation of activated mast cell in the shoulder region of human coronary atheroma, the predilection site of atheromatous rupture. Circulation. 1994;90:1669–1678. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.4.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bot I., Biessen E. A. Mast cells in atherosclerosis. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2011;106:820–826. doi: 10.1160/TH11-05-0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deliargyris E. N., Upadhya B., Sane D. C., Dehmer G. J., Pye J., Smith S. C., Jr, Boucher W. S., Theoharides T. C. Mast cell tryptase: a new biomarker in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2005;178:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiang M., Sun J., Lin Y., Zhang J., Chen H., Yang D., Wang J., Shi J. P. Usefulness of serum tryptase level as an independent biomarker for coronary plaque instability in a Chinese population. Atherosclerosis. 2011;215:494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kervinen H., Kaartinen M., Mäkynen H., Palosuo T., Mänttäri M., Kovanen P. T. Serum tryptase levels in acute coronary syndromes. Int. J. Cardiol. 2005;104:138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee M., Kovanen P. T., Tedeschi G., Oungre E., Franceschini G., Calabresi L. Apolipoprotein composition and particle size affect HDL degradation by chymase: effect on cellular cholesterol efflux. J. Lipid Res. 2003;44:539–546. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200420-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Usami Y., Matsuda K., Sugano M., Ishimine N., Kurihara Y., Sumida T., Yamauchi K., Tozuka M. Detection of chymase-digested C-terminally truncated apolipoprotein A-I in normal human serum. J. Immunol. Methods. 2011;369:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pejler G., Knight S. D., Henningsson F., Wernersson S. Novel insights into the biological function of mast cell carboxypeptidase A. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein S. M., Leong J., Schwartz L. B., Cooke D. Protease composition of exocytosed human skin mast cell protease-proteoglycan complexes. Tryptase resides in a complex distinct from chymase and carboxypeptidase. J. Immunol. 1992;148:2475–2482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundequist A., Tchougounova E., Abrink M., Pejler G. Cooperation between mast cell carboxypeptidase A and the chymase mouse mast cell protease 4 in the formation and degradation of angiotensin II. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:32339–32344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405576200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Havel R. J., Eder H. A., Bragdon J. H. The distribution and chemical composition of ultracentrifugally separated lipoproteins in human serum. J. Clin. Invest. 1955;9:1345–1353. doi: 10.1172/JCI103182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghiselli G., Rohde M. F., Tanenbaum S., Krishnan S., Gotto A. M., Jr Origin of apolipoprotein A-I polymorphism in plasma. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:15662–15668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lund-Katz S., Phillips M. C. High density lipoprotein structure-function and role in reverse cholesterol transport. Subcell. Biochem. 2010;51:183–227. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-8622-8_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva R. A., Hilliard G. M., Fang J., Macha S., Davidson W. S. A three-dimensional molecular model of lipid-free apolipoprotein A-I determined by cross-linking/mass spectrometry and sequence threading. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2759–2769. doi: 10.1021/bi047717+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ajees A. A., Anantharamaiah G. M., Mishra V. K., Hussain M. M., Murthy H. M. K. Crystal structure of human apolipoprotein A-I: insights into its protective effect against cardiovascular disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:2126–2131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506877103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Palgunachari M. N., Mishra V. K., Land-Katz S., Phillips M. C., Adeyeye S. O., Alluri S., Anantharamaiah G. M., Segrest J. P. Only the two end helixes of eight tandem amphipathic helical domains of human apoA-I have significant lipid affinity. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1996;16:328–338. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saito H., Dhanasekaran P., Nguyen D., Holvoet P., Lund-Katz S., Phillips M. C. Domain structure and lipid interaction in human apolipoproteins A-I and E, a general model. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:23227–23232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kono M., Okumura Y., Tanaka M., Nguyen D., Dhanasekaran P., Lund-Katz S., Phillips M. C., Saito H. Conformational flexibility of the N-terminal domain of apolipoprotein A-I bound to spherical lipid particles. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11340–11347. doi: 10.1021/bi801503r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Church M. K., Levi-Shaffer F. The human mast cell. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1997;99:155–160. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laine P., Kaatinen M., Penttilä A., Panula P., Paavonen T., Kovanen P. T. Association between myocardial infarction and the mast cells in the adventitia of the infarct-related coronary artery. Circulation. 1999;99:361–369. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindstedt L., Lee M., Kovanen P. T. Chymase bound to heparin is resistant to its natural inhibitors and capable of proteolysing high-density lipoproteins in aortic intimal fluid. Atherosclerosis. 2001;155:87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00544-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filippis D., D’amico A., Iuvone T. Cannabinomimetic control of mast cell mediator release: new perspective in chronic inflammation. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:20–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krishnaswamy G., Ajitawi O., Chi D. S. The human mast cell: an overview. Methods Mol. Biol. 2006;315:13–34. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-967-2:013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]