Aberrant activation of the innate immune system in metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes has been recognized to be an important mechanism of disease pathogenesis (1–3). Emergence of a chronic proinflammatory state driven by the activation of myeloid lineage innate immune cells, such as macrophages and neutrophils, has been directly linked to the emergence of insulin resistance (4,5). Until recently, the identity of specific innate immune pattern recognition receptors or sensors that recognize diverse metabolic “danger signals” to initiate a proinflammatory cascade during obesity and diabetes was unknown. Pioneering studies from Tschopp and colleagues (6) identified that “inflammasomes,” the multiprotein cytosolic molecular platforms in myeloid cells, can sense damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and control the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 in metabolic stress. Structurally, inflammasomes consist of a Nod-like receptor (NLR), the apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC) adaptor protein, and caspase-1 (6). Several NLR molecules including NLRP1, NLRP3, and NLRC4 control caspase-1 activation, which controls the cleavage and secretion of pro–IL-1β and pro–IL-18 into bioactive cytokines (6). Several studies using genetically modified mice that lack inflammasome components Nlrp3, Asc, and caspase-1 provided initial evidence that activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome is a key mechanism that induces metabolic inflammation and insulin resistance (7–10). Deactivation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome in obese type 2 diabetic patients that lose excess weight through lifestyle intervention is coupled with improved glucose homeostasis, suggesting that inflammasome may be a clinically relevant mechanism that links inflammation with type 2 diabetes (7). However, there is scant clinical evidence that myeloid cells of type 2 diabetic patients have elevated Nlrp3 inflammasome activation, and it is not clear whether the mechanism of inflammasome activation observed in rodent models applies to human metabolic disease.

In this issue of Diabetes, Lee et al. (11) report that monocytes derived from newly identified untreated type 2 diabetic patients display elevated expression of inflammasome components Nlrp3 and Asc, along with increased caspase-1 activation. Consistent with elevated Nlrp3 inflammasome activation in myeloid cells, the drug-naïve type 2 diabetic patients (n = 47) had significantly high serum levels of IL-1β and IL-18 compared with healthy subjects (n = 57). The studies from knock-in reporter mice in which Nlrp3 coding sequence is substituted with green fluorescent protein demonstrate that the Nlrp3 inflammasome is predominantly active in myeloid cells (12). In the current article, Lee et al. demonstrate that monocytes derived from peripheral blood of type 2 diabetic patients have increased basal Nlrp3 inflammasome activation (11). In addition, compared with cells from healthy participants, the myeloid cells of type 2 diabetic patients respond with elevated caspase-1 activation and produce higher levels of IL-1β and IL-18 when exposed to metabolic danger signals such as urate, free fatty acids, and extracellular ATP (11) (Fig. 1). The increased levels of elevated free fatty acids that induce lipotoxicity (7,8) and higher uric acid levels (13) are known to increase the risk of development of diabetes and its complications. The release of ATP from necrotic cells is also a potent trigger of inflammasome activation (14). Therefore, it is possible that these metabolic DAMPs that are produced as a result of metabolic dysfunction trigger the activation the Nlrp3 inflammasome (Fig. 1). The knockdown of Nlrp3 and Asc via RNA interference in myeloid cells of type 2 diabetic patients prevented the ability of metabolic DAMPs to induce IL-1β and IL-18 secretion (11). Thus, Lee et al. also demonstrate the specificity of the Nlrp3 inflammasome in inducing inflammation originating from myeloid cells of drug-naïve diabetic patients.

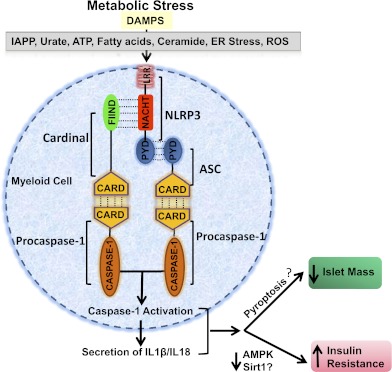

FIG. 1.

Hypothetical model depicting the role of Nlrp3 inflammasome in type 2 diabetes. Metabolic stress–induced “danger signals” in type 2 diabetes such as islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP), urate, extracellular ATP, fatty acids, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) can be sensed by Nlrp3 inflammasome. The assembly of activated Nlrp3 inflammasome in myeloid cells by protein-protein interaction between Nlrp3, Asc, and (Cardinal) with procaspase-1 causes caspase-1 cleavage into P20 and P10 enzymatically active heterodimers that causes posttranslational processing of IL-1β and IL-18. Inflammation induced by inflammasome-dependent proinflammatory cytokines may produce insulin resistance or cause death of pancreatic β-cells leading to development of diabetes. AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; Sirt1, sirtuin 1.

Depending on specific DAMPs that are encountered by a myeloid lineage cells, several mechanisms control the assembly and activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome (2). These include defective autophagy, unfolded protein response, and oxidative stress (15,16). Metabolic distress, inflammation, and development of insulin-resistance are linked to increased oxidative stress emerging from mitochondria and unfolded protein response due to defective endoplasmic reticulum function (6,17). Consistent with studies in animal models (18), Lee et al. found that hyperglycemia-induced elevated mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in myeloid cells of type 2 diabetic patients is associated with increased production of inflammasome-dependent cytokines IL-1β and IL-18. Together with prior studies from Ting and colleagues (8), the current data from myeloid cells of type 2 diabetic patients corroborate the earlier findings that inhibition of AMP-activated protein kinase can exacerbate reactive oxygen species–dependent Nlrp3 inflammasome activation (11). Importantly, Lee et al. show that the 2-month long treatment of drug-naïve type 2 diabetic patients with the antidiabetic drug, metformin, which is known to activate AMP-activated protein kinase, reversed the increase in caspase-1 activation and the production of IL-1β and IL-18 from myeloid cells.

Despite several mechanistic studies that show clear evidence of inflammation in pathogenesis of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, few drugs that dampen metabolically driven inflammation have shown success in the treatment of diabetes. Initial clinical studies reported encouraging findings that the nonglycosylated version of human IL-1 receptor antagonist, Anakinra, which blocks IL-1β signaling, improves glycemic control and reduces HbA1c in type 2 diabetic patients (3). This clinical trial reported increased β-cell secretory capacity but did not detect any changes in insulin resistance despite reduction in serum C-reactive protein (3). Importantly, ablation of Nlrp3 and Asc in chronically obese mice leads to increased islet size and protection of β-cells in pancreatic islets from inflammation-induced death (19). Although the work conducted by Lee et al. represents progress in the field that shows important clinical association between Nlrp3 inflammasome activation in myeloid cells and type 2 diabetes, it remains to be substantiated whether inhibition of Nlrp3 inflammasome represents a viable therapeutic strategy to control diabetes. Also, earlier studies have reported that hyperglycemia induces caspase-1 activation in adipose tissue and adipocytes (20). Studies using human adipose biopsies have shown an association between increased caspase-1 and Nlrp3 inflammasome activity to insulin resistance (21). From the current study it is not clear whether the preactivated myeloid cells from blood infiltrate the adipose depots to mediate inflammation-induced insulin resistance.

A recent press release of a study that awaits publication in a peer reviewed journal (22) reported that Xoma-052, a monoclonal antibody that effectively blocks IL-1β signaling, failed to lower blood glucose levels in 421 type 2 diabetic patients in a phase 2 clinical study. Therefore, despite promising mechanistic studies that identified Nlrp3 inflammasome as a central regulator of metabolic inflammation, the therapeutic potential of reversing type 2 diabetes by dampening inflammasome-dependent downstream cytokines remains to be realized. It has been suggested that once cleaved, caspase-1 can modify activity of several proteins other than just IL-1β and IL-18 (6). Interestingly, recent work demonstrates that high-fat diet feeding–induced caspase-1 deactivates Sirtuin 1 and leads to insulin resistance (23). Hence, additional studies would be needed to test whether the specific inflammasome or caspase-1 inhibitors can prove to be better alternatives to IL-1β inhibition as treatment for diabetes.

In summary, the work by Lee et al. represents an important step in the direction to understand clinical relevance of the Nlrp3 inflammasome activation in diabetes. This study provides evidence that the Nlrp3 inflammasome activation in myeloid cells of type 2 diabetic patients contributes to the chronic proinflammatory state. Future research to identify specific molecular mechanism of immune-metabolic interactions that lead to organ dysfunction from chronic inflammatory damage may produce novel strategies to manage type 2 diabetes and its complications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

V.D.D. is supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-AG031797 and R01-DK090556.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Footnotes

See accompanying original article, p. 194.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hotamisligil GS, Erbay E. Nutrient sensing and inflammation in metabolic diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2008;8:923–934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanneganti TD, Dixit VD. Immunological complications of obesity. Nat Immunol 2012;13:707–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2011;11:98–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talukdar S, Oh DY, Bandyopadhyay G, et al. Neutrophils mediate insulin resistance in mice fed a high-fat diet through secreted elastase. Nat Med 2012;18:1407–1412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chawla A, Nguyen KD, Goh YP. Macrophage-mediated inflammation in metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2011;11:738–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schroder K, Zhou R, Tschopp J. The NLRP3 inflammasome: a sensor for metabolic danger? Science 2010;327:296–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vandanmagsar B, Youm YH, Ravussin A, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Med 2011;17:179–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen H, Gris D, Lei Y, et al. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol 2011;12:408–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stienstra R, Joosten LA, Koenen T, et al. The inflammasome-mediated caspase-1 activation controls adipocyte differentiation and insulin sensitivity. Cell Metab 2010;12:593–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stienstra R, van Diepen JA, Tack CJ, et al. Inflammasome is a central player in the induction of obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:15324–15329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee H-M, Kim J-J, Kim HJ, Shong M, Ku BJ, Jo E-K. Upregulated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2013;62:194–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Guarda G, Zenger M, Yazdi AS, et al. Differential expression of NLRP3 among hematopoietic cells. J Immunol 2011;186:2529–2534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jalal DI, Maahs DM, Hovind P, Nakagawa T. Uric acid as a mediator of diabetic nephropathy. Semin Nephrol 2011;31:459–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, et al. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature 2006;440:228–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 2011;469:221–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lerner AG, Upton JP, Praveen PV, et al. IRE1α Induces Thioredoxin-Interacting Protein to Activate the NLRP3 Inflammasome and Promote Programmed Cell Death under Irremediable ER Stress. Cell Metab 2012;16:250–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell 2010;140:900–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, Choi I, Tschopp J. Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol 2010;11:136–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Youm YH, Adijiang A, Vandanmagsar B, Burk D, Ravussin A, Dixit VD. Elimination of the NLRP3-ASC inflammasome protects against chronic obesity-induced pancreatic damage. Endocrinology 2011;152:4039–4045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koenen TB, Stienstra R, van Tits LJ, et al. Hyperglycemia activates caspase-1 and TXNIP-mediated IL-1beta transcription in human adipose tissue. Diabetes 2011;60:517–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goossens GH, Blaak EE, Theunissen R, et al. Expression of NLRP3 inflammasome and T cell population markers in adipose tissue are associated with insulin resistance and impaired glucose metabolism in humans. Mol Immunol 2012;50:142–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.XOMA 052 phase 2b top line results: Glucose control not demonstrated, positive anti-inflammatory effect, cardiovascular biomarker and lipid improvement and safety confirmed [press release online], 2011. Available from http://investors.xoma.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=559470 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chalkiadaki A, Guarente L. High-fat diet triggers inflammation-induced cleavage of sirt1 in adipose tissue to promote metabolic dysfunction. Cell Metab 2012;16:180–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]