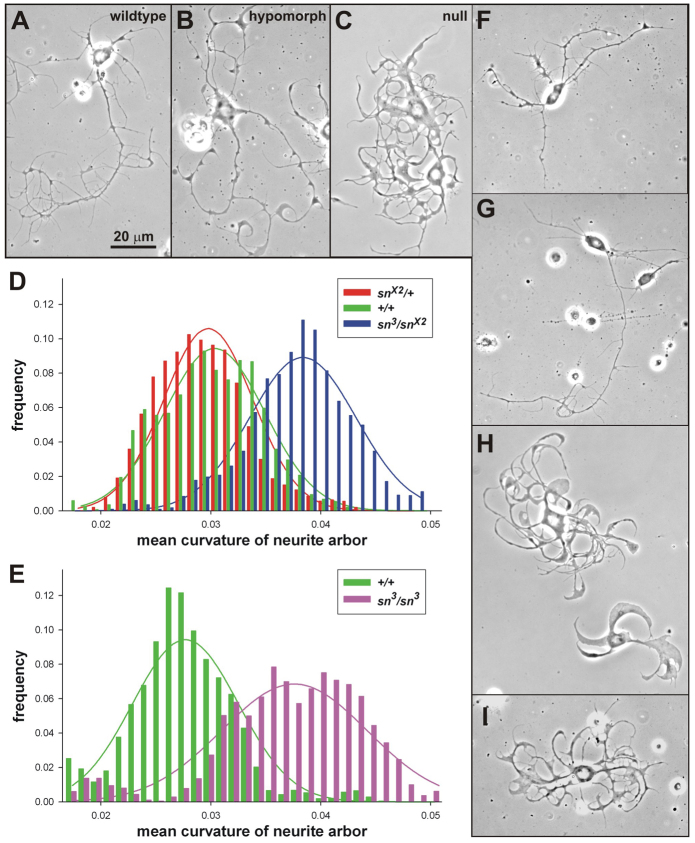

Fig. 1.

Genetic and pharmacological modification of neurite curvature. (A–C,F–I) Phase-contrast images (60×) of neurons cultured for 3 d.i.v. from the CNS of wandering third instar larvae. Magnification is the same throughout. (A–C) Loss-of-function singed mutations increase neurite curvature and disrupt proximal-to-distal tapering. (A) Wild-type (sn+/sn+), OreR-C laboratory strain. (B) A partial loss-of-function (hypomorphic) mutation (sn3/sn3) causes a moderate filagree phenotype. (C) A null mutation (snX2/Y) causes a severe filagree phenotype. (D,E) Mean curvature distributions of neurite arbors of cultured neurons with differing genotypes, plotted with soft binning. Normal-distribution curves were fit to each population and scaled (y-axis) to the corresponding histograms. (D) Genetically marked γ-MB neurons. The increased curvature of sn3/snX2 (blue) neurons is easily seen. The similarity of snX2/+(red) and sn+/sn+ (green) curvature distributions demonstrates that filagree is recessive. (E) Random CNS neurons. The mean neurite curvature distribution of sn3/sn3 mutant neurons (magenta) is significantly increased over that of wild-type (sn+/sn+, OreR-C) neurons (green). (F–I) Exposure to drugs in vitro can modify the filagree phenotype of fascin-deficient sn3/sn3 neurons. (F,G) Two examples of filagree decreasers (fascin-pathway enhancers): estradiol propionate, 50 μM (E) and Anisindione, 50 μM (G). Neurite curvature, especially of terminal neurites, is reduced and the smooth proximal-to-distal tapering is restored. (H,I) Two examples of filagree increasers (fascin-pathway blockers): griseofulvin, 50 μM (H) and acetyltryptophan, 50 μM (I). Note the exaggerated neurite curvature and frequent expansions of neurite width.