Abstract

Introduction

The Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) measures health status and can be used to assess health-related quality of life (HRQL). We investigated whether CCQ is also associated with mortality.

Methods

Some 1111 Swedish primary and secondary care chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients were randomly selected. Information from questionnaires and medical record review were obtained in 970 patients. The Swedish Board of Health and Welfare provided mortality data. Cox regression estimated survival, with adjustment for age, sex, heart disease, and lung function (for a subset with spirometry data, n = 530). Age and sex-standardized mortality ratios were calculated.

Results

Over 5 years, 220 patients (22.7%) died. Mortality risk was higher for mean CCQ ≥ 3 (37.8% died) compared with mean CCQ < 1 (11.4%), producing an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) (and 95% confidence interval [CI]) of 3.13 (1.98 to 4.95). After further adjustment for 1 second forced expiratory volume (expressed as percent of the European Community for Steel and Coal reference values ), the association remained (HR 2.94 [1.42 to 6.10]). The mortality risk was higher than in the general population, with standardized mortality ratio (and 95% CI) of 1.87 (1.18 to 2.80) with CCQ < 1, increasing to 6.05 (4.94 to 7.44) with CCQ ≥ 3.

Conclusion

CCQ is predictive of mortality in COPD patients. As HRQL and mortality are both important clinical endpoints, CCQ could be used to target interventions.

Keywords: health status, Health Related Quality of Life (HRQL), Standardized Mortality Ratios (SMR)

Introduction

The assessment of severity and prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is traditionally based on lung function.1 In chronic diseases, health-related quality of life (HRQL) is an important patient-oriented measurement of the impact of health on well-being.2 HRQL reflects the subjective experience of health status on the quality of life.3 Previous studies have shown that the extensive HRQL instrument, St Georges Respiratory Questionnaire, is predictive of mortality.4–9 In contrast, a study using the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire6 failed to demonstrate an association with mortality. Using another instrument, the Seattle Obstructive Lung Disease Questionnaire, an association was shown only for the functional domain.10

In most clinical settings extensive HRQL instruments are too time-consuming to use. The Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) benefits from comprising only ten items,11–13 and its brevity and simplicity makes it particularly suitable for routine use in clinical practice. The CCQ was originally created to measure clinical health status in patients, including symptoms of the airways, limitation of physical activity, and emotional dysfunction.11 Health status has an important influence on HRQL, and since the CCQ has been shown to correlate well with the St Georges Respiratory Questionnaire,11 the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire14 and with the generic HRQL instrument SF-36®,11 it can be used for estimating HRQL.15–17 However, the prognostic qualities of the CCQ have not yet been evaluated in terms of mortality. If this brief instrument could predict both HRQL and mortality risk, it would emphasize the importance of measuring health status relevant to HRQL, in addition to more conventional measurements.

The aim of this multicenter study was to examine the associations of the CCQ score for all-cause and cause-specific mortality in COPD patients from both primary and secondary care clinics in Sweden. In addition, we examined whether mortality in COPD patients with different CCQ scores is raised compared with the normal population.

Methods

Procedure

The population was sampled from a larger cohort involved in an investigation of asthma and COPD in seven Swedish county councils.17–19 Each Swedish county council has a central hospital and one or more district hospitals. In this study, each county council was represented by the Department of Respiratory Medicine in their central hospital, the Department of Internal Medicine from one randomly selected district hospital and eight randomly selected primary health care centers (PHCCs), in total 14 hospitals and 56 PHCCs. A list of all patients aged 18–75 years with a COPD diagnosis (ICD-10 code J44) in the medical records during the period of 2000–2003 was compiled for every participating primary and secondary care center. Random selection was used to recruit 35 COPD patients per hospital list and 22 COPD patients per PHCC list. In twelve PHCCs, where the original list contained fewer than 22 patients, everyone on the list was included. The sample comprised 1548 patients aged 34–75 years, including 1084 from primary and 464 from secondary care.

Data collection

Data were collected by self-completion questionnaire in 2005 and by medical record review for the period of 2000–2003. The response rate for the questionnaire was 75%. Of those who responded, 98% (1111 patients) consented to a review of their medical records. The Swedish Board of Health and Welfare provided mortality data for 2005 to 2010, including the underlying cause of death from death certificates. Two research nurses recorded the data from the patient questionnaires and medical records.

Measures

Information on age, sex, level of education, height, weight, smoking habits, exacerbation rate, maintenance treatment, and vaccination status was collected using the patient questionnaires. Age was categorized in age groups of <50 years, 51–60 years, 61–70 years, and >70 years. In Sweden, education at school is compulsory for 9 years. In our study, the dichotomous educational variable identified the most educated group as those who had continued in full-time education for at least 2 years beyond the compulsory school period. Obesity was defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥30, overweight as BMI <30 and ≥25, and underweight as BMI <20. Smoking was categorized into nonsmokers, ex-smokers, occasional smokers (smoking less frequently than daily), and current smokers. An exacerbation was defined as an unscheduled or emergency visit due to worsening of their COPD, or a course of oral steroids. To ensure that only true COPD exacerbations were included, emergency visits leading to treatment with antibiotics but not steroids were not classified as exacerbations. Four separate binary treatment category variables were created for: no maintenance therapy besides short-acting beta-agonists or ipratropium; maintenance therapy with tiotropium or long-acting beta-agonists; inhalation corticosteroids alone; and inhalation corticosteroids combined with long-acting beta-agonists or tiotropium therapy. We created two vaccination status variables for influenza vaccination: last year; and pneumococcal vaccination within the recent 5 years.

Information about comorbid diagnoses and lung function was gathered from patient records for the period of 2000–2003. Heart disease was defined as the presence of ischemic heart disease or heart failure; diabetes as type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus; depression as having a diagnosis of depression, in combination with antidepressant drug treatment; and asthma was identified where the ICD code J45 was recorded during the study period. Lung function data were available in 594 (53%) of the 1111 patients records. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) was expressed as percent of the European Community for Steel and Coal reference values (FEV1%pred).20 Information on cause-specific mortality was categorized as: death by respiratory disease; cardiovascular disease; cancer; and other causes of death.

CCQ

The patient questionnaire included a validated Swedish version of the CCQ.21 The CCQ consists of ten questions distributed in three domains: symptoms, mental state, and functional state. Observed symptoms are dyspnea, cough, and phlegm; mental state includes questions about feeling depressed and concerns about breathing; and functional state describes limitations in different activities of daily life due to the lung disease. The questions apply to the previous week and use a seven-point scale from zero to six. The main outcome measure of HRQL is the CCQ total score, calculated as the mean of the sum of all items,11 with a higher value indicating lower health status. The minimal difference in CCQ score considered to be of clinical importance is 0.4.12 In our study, CCQ score was expressed both as the CCQ total score and as mean scores of the domains.11 To assess the severity of disease, the CCQ score was divided into four groups defined by its creator:22 <1p was considered acceptable; ≥1p but <2p was acceptable only in patients with COPD stage 3 or 4; ≥2 but <3p was considered unstable; and ≥3p was indicative of very unstable health status.

Standardized mortality ratios (SMR)

To compare death rates in our cohort with the general Swedish population, SMR were calculated for the entire cohort and for each different group of CCQ total score. The expected numbers of deaths were obtained using age-, sex-, and date-specific rates from the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare.23

Statistical analysis

The analyses were performed using PASW version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Study entry was defined as the date when the patients received their questionnaires. Follow-up time was defined as the time from study entrance until death or the end of the study in September 2010.

Kaplan–Meier and Cox regression analyses were used to assess univariate associations with mortality for age, sex, smoking status, level of education, heart disease, diabetes, depression, body mass index, exacerbations, CCQ total score, and FEV1%pred. All variables except FEV1%pred were combined in a multivariate Cox regression analysis, and based on the result, a main model estimating survival by CCQ total score adjusted for age, sex, and heart disease was created. Complete data for all the variables in this main analysis were available for 970 patients. To examine the influence of a contemporaneous asthma diagnosis, additional analyses were performed, first with additional adjustment for a diagnosis of asthma and then with exclusion of the patients with an asthma diagnosis.

A subgroup analysis, for the association of CCQ total score with all-cause mortality, was performed for patients with spirometry data (n = 530). Cox regression was used to assess cause-specific mortality associations with CCQ total score, after adjustment for age and sex. The associations with mortality for the domains of the CCQ score were examined using Cox regression analysis before and after adjustment for sex, age, and heart disease. Stratification and interaction analyses were used to investigate sex differences in the association of CCQ total score with mortality. The interaction analyses used interaction terms for sex with the CCQ modeled in the four previously described categories, with adjustment for the main effects, as well as for age and heart disease. Potential effect modification by age dichotomized at 70 years was similarly investigated using stratification and interaction analyses. The Cox regression analyses for the CCQ total score were repeated with further adjustment for treatment and vaccination status. The SMR were calculated as the ratio of observed and expected deaths for the entire cohort and for each different group of CCQ total scores. The standardization was for sex and age (in 5-year age groups).

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Uppsala University (Dnr 2010/090). Written consent was obtained for all participating patients.

Results

Patient characteristics

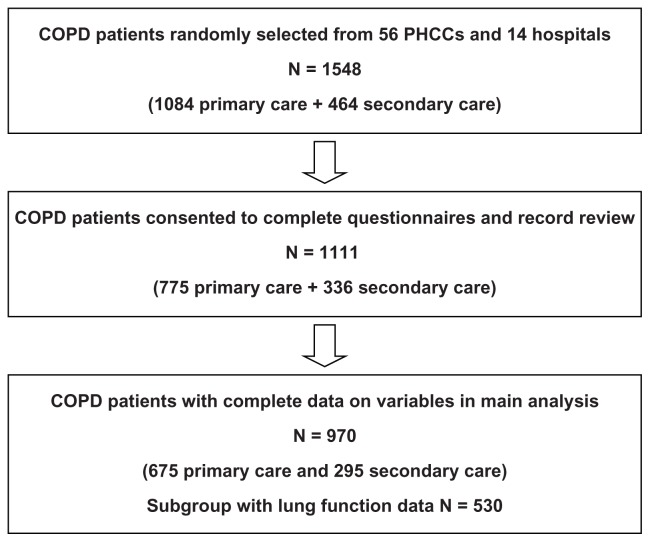

The final study population with complete data for all variables in the main analysis included 970 patients (Figure 1). During the average study period of 5 years, 220 patients (22.7%) died. Information on the cause of death was available for 217 patients (98.6%). Patient characteristics are described in Table 1. The mortality rate was higher among men; among patients in secondary care; among older patients; and in patients with lower education and comorbid heart disease and who were underweight. Having no maintenance therapy was more common among patients alive at the end of the study period, and influenza/pneumococcal vaccinations were more common among patients who died during the follow up. Univariate Cox regression analyses showed that male sex, older age, higher education, higher stage of COPD, CCQ total score, underweight, frequent exacerbations, and heart disease were statistically significantly associated with raised mortality. When all variables were included in a multivariate Cox regression age, CCQ score and heart disease remained statistically significantly associated with mortality (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Patient population flow chart.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PHCC, primary health care center.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| All (n) | Dead (n) | Dead (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 970 | 220 | 22.7 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 412 | 109 | 26.5 | Ref |

| Female | 558 | 111 | 19.9 | 0.016 |

| Age | ||||

| ≤50 | 64 | 3 | 4.7 | <0.0001 |

| 51–60 | 194 | 19 | 9.8 | <0.0001 |

| 61–70 | 490 | 118 | 24.1 | 0.001 |

| >70 | 222 | 80 | 36.0 | Ref |

| Educational level | ||||

| Lower | 641 | 157 | 24.5 | Ref |

| Higher | 316 | 59 | 18.7 | 0.043 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never | 61 | 10 | 16.4 | 0.544 |

| Ex | 574 | 143 | 24.9 | 0.099 |

| Occasional | 61 | 13 | 21.3 | 0.787 |

| Current | 273 | 54 | 19.8 | Ref |

| Level of care | ||||

| Primary care | 675 | 122 | 18.1 | Ref |

| Secondary care | 295 | 98 | 33.2 | <0.0001 |

| Heart disease | ||||

| Yes | 225 | 88 | 39.1 | <0.0001 |

| No | 745 | 132 | 17.7 | Ref |

| Body mass index | ||||

| Underweight | 103 | 34 | 33.0 | 0.049 |

| Normal weight | 331 | 77 | 23.3 | Ref |

| Overweight | 334 | 60 | 18.0 | 0.092 |

| Obesity | 175 | 40 | 22.9 | 0.918 |

| Influenza vaccination | ||||

| Yes | 507 | 135 | 26.6 | 0.002 |

| No | 463 | 85 | 18.4 | Ref |

| Pneumococcal vaccination | ||||

| Yes | 333 | 97 | 29.1 | <0.0001 |

| No | 637 | 123 | 19.3 | Ref |

| Treatment | ||||

| No except SABA or ipratropium | 213 | 24 | 11.3 | <0.0001 |

| LABA or tiotropium* | 87 | 23 | 26.4 | 0.997 |

| ICS alone** | 106 | 24 | 22.9 | 0.416 |

| ICS with LABA or tiotropium*** | 564 | 149 | 26.4 | Ref |

| CCQ total score | ||||

| <1 | 201 | 23 | 11.4 | Ref |

| ≥1, <2 | 251 | 34 | 13.5 | 0.504 |

| ≥2, <3 | 243 | 59 | 24.3 | 0.001 |

| ≥3 | 275 | 104 | 37.8 | <0.0001 |

| COPD stage**** | ||||

| Stage 1 | 150 | 13 | 8.7 | Ref |

| Stage 2 | 211 | 33 | 15.6 | <0.0001 |

| Stage 3 | 131 | 47 | 35.9 | <0.0001 |

| Stage 4 | 38 | 16 | 42.1 | 0.485 |

Notes:

Maintenance treatment with LABA and/or tiotropium but not ICS;

maintenance treatment with ICS but not LABA or tiotropium;

maintenance treatment with ICS and LABA separately or in a fixed combination, or ICS and tiotropium;

subgroup with lung function data, n = 530.

Abbreviations: SABA, short-acting beta-agonist; LABA, long-acting beta-agonist; ICS, inhalation corticosteroid; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CCQ, clinical COPD Questionnaire.

Main analysis

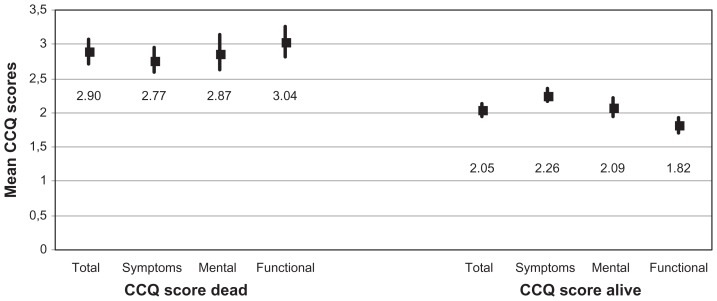

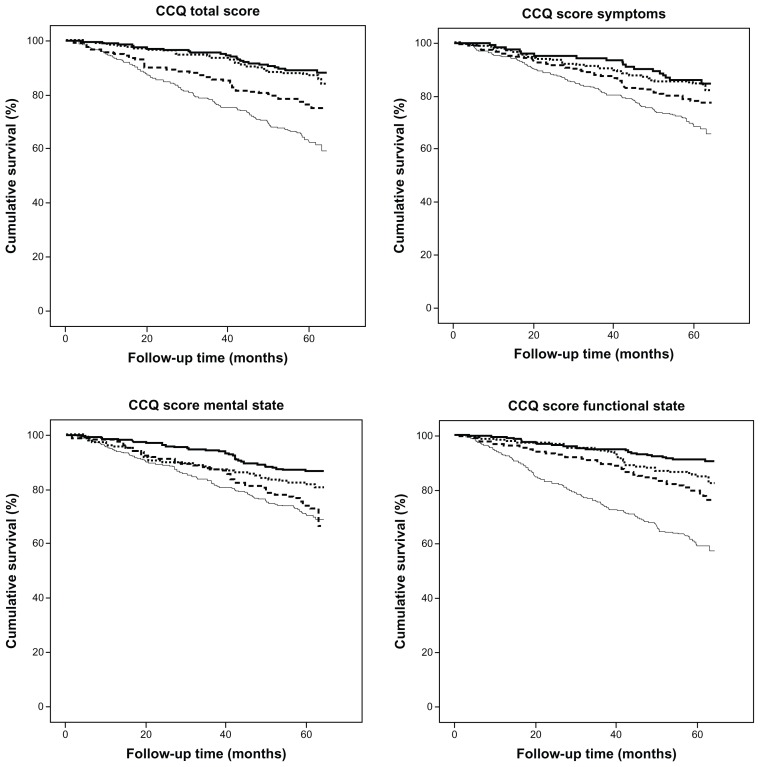

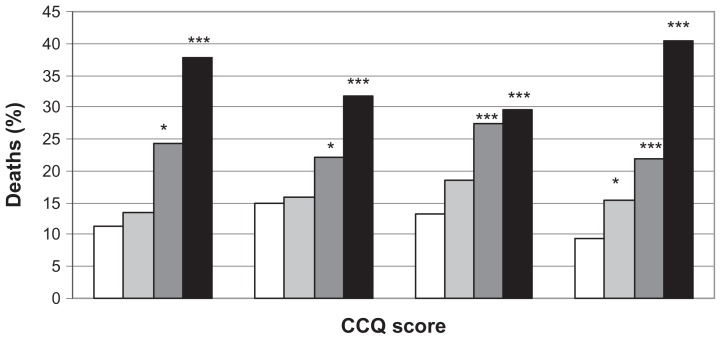

The CCQ total score was 2.05 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.95 to 2.14) among alive participants and 2.90 (2.71 to 3.08) among participants who died during the study period (Figure 2). The CCQ total and domain scores are shown in Figure 2. Mortality was higher in patients with CCQ total score ≥3 (37.8%) and in patients with CCQ total score ≥2 and <3 (24.3%) than in stable patients with CCQ total score <1 (11.4%). The association between CCQ and mortality is shown in Figures 3 and 4. In the two patient groups with the highest CCQ total score, mortality risk after adjustment for sex, age, and heart disease was statistically significantly and independently higher than in stable COPD patients with CCQ total score <1 (Table 2).

Figure 2.

CCQ total and domain scores.

Note: Mean scores including 95% confidence intervals among dead and alive participants.

Abbreviations: CCQ, Clinical COPD Questionnaire; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Figure 3.

CCQ score and mortality.

Notes: Kaplan–Meier curves for CCQ total and domain mean scores. Solid line = CCQ mean score <1; dotted line = CCQ mean score ≥1 and <2; broken line = CCQ mean score ≥2 and <3; thin line = CCQ mean score ≥3.

Abbreviation: CCQ, Clinical COPD Questionnaire.

Figure 4.

Deaths (%) by CCQ total and domain mean scores.

Notes: White field = CCQ score < 1; light grey field = CCQ score > 1 and <2; dark grey field CCQ score > 2 and <3; black field CCQ score > 3. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001.

Abbreviation: CCQ, Clinical COPD Questionnaire.

Table 2.

Results Cox regression CCQ score and mortality

| HR (95%CI) Unadjusted | P-value | HR (95%CI) adjusted | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCQ total score* | ||||

| <1 | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≥1, <2 | 1.21 (0.71 to 2.05) | 0.490 | 0.98 (0.57 to 1.66) | 0.925 |

| ≥2, <3 | 2.34 (1.44 to 3.79) | 0.001 | 1.96 (1.21 to 3.18) | 0.007 |

| ≥3 | 3.98 (2.53 to 6.25) | <0.0001 | 3.13 (1.98 to 4.95) | <0.0001 |

| Sex* | ||||

| Male | Ref | Ref | ||

| Female | 0.71 (0.54 to 0.92) | 0.010 | 0.94 (0.71 to 1.23) | 0.650 |

| Age* | ||||

| ≤50 | 0.11 (0.03 to 0.34) | <0.0001 | 0.15 (0.05 to 0.48) | 0.001 |

| 51–60 | 0.23 (0.14 to 0.38) | <0.0001 | 0.28 (0.17 to 0.46) | <0.0001 |

| 61–70 | 0.63 (0.47 to 0.84) | 0.001 | 0.73 (0.55 to 0.98) | 0.034 |

| >70 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Heart disease* | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.62 (2.00 to 3.43) | <0.0001 | 1.90 (1.43 to 2.52) | <0.0001 |

| CCQ domain scores** | ||||

| Symptoms | ||||

| <1 | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≥1, <2 | 1.11 (0.64 to 1.92) | 0.718 | 0.97 (0.56 to 1.69) | 0.911 |

| ≥2, <3 | 1.59 (0.94 to 2.70) | 0.084 | 1.24 (0.73 to 2.11) | 0.431 |

| ≥3 | 2.42 (1.47 to 4.00) | 0.001 | 1.99 (1.20 to 3.31) | 0.008 |

| Mental state | ||||

| <1 | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≥1, <2 | 1.48 (0.92 to 2.36) | 0.104 | 1.33 (0.83 to 2.12) | 0.240 |

| ≥2, <3 | 2.24 (1.44 to 3.49) | <0.0001 | 2.05 (1.32 to 3.21) | 0.002 |

| ≥3 | 2.52 (1.72 to 3.69) | <0.0001 | 2.38 (1.62 to 3.50) | <0.0001 |

| Functional state | ||||

| <1 | Ref | Ref | ||

| >1, <2 | 1.71 (1.01 to 2.89) | 0.044 | 1.34 (0.79 to 2.27) | 0.280 |

| >2, <3 | 2.50 (1.54 to 4.08) | <0.0001 | 1.86 (1.13 to 3.05) | 0.014 |

| >3 | 5.37 (3.48 to 8.27) | <0.0001 | 4.00 (2.57 to 6.21) | <0.0001 |

| CCQ total score*** (subgroup) | ||||

| <1 | Ref | Ref | ||

| >1, <2 | 1.17 (0.52 to 2.64) | 0.700 | 0.90 (0.40 to 2.07) | 0.811 |

| >2, <3 | 2.59 (1.26 to 5.32) | 0.010 | 1.68 (0.79 to 3.55) | 0.175 |

| >3 | 5.14 (2.63 to 10.1) | <0.0001 | 2.94 (1.42 to 6.10) | 0.004 |

Notes:

Multivariate analysis including CCQ total score, sex, age, and heart disease;

multivariate analysis including CCQ domain scores, sex, age, and heart disease;

multivariate analysis including CCQ total score, sex, age, heart disease, and lung function.

Abbreviations: CCQ, Clinical COPD Questionnaire; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

In the study population of 970 COPD patients, 207 had a contemporaneous asthma diagnosis. After further adjustment for asthma diagnoses, the hazard ratios (HRs) for mortality associated with CCQ >1 and <2, and CCQ ≥2 and <3 were 1.96 (1.21 to 3.18) and 3.12 (1.97 to 4.93), respectively. In the group of 763 patients with COPD and no contemporaneous asthma diagnosis, the HRs for the association with mortality were 2.25 (1.29 to 3.92) for CCQ ≥1 and <2, and 3.83 (2.26 to 6.51) for CCQ ≥2 and <3. These results indicate that the associations with mortality were not explained or influenced substantially by the presence of asthma.

Subgroup with spirometry data

In the subset of patients with spirometry data (n = 530), the difference in total CCQ score was also statistically significantly higher among dead (2.98, 95% CI: 2.75 to 3.23) compared with alive participants (2.04, 95% CI: 1.92 to 2.17). CCQ total score ≥3 and ≥2 but <3 was statistically significantly and independently associated with higher mortality compared with CCQ total score <1, before (Table 2) and after adjustment for sex, age, and heart disease. After further adjustment for stage of COPD, CCQ total score ≥3 remained statistically significantly associated with higher mortality (Table 2).

When we stratified by presence of spirometry data, the association of CCQ with mortality did not differ notably between the strata. In the subgroup with spirometry data (n = 530), after adjustment for age, sex, and heart disease for the association of CCQ with mortality, the HR was 4.30 (2.17 to 8.51) for CCQ total score ≥3 and 2.15 (1.03 to 4.47) for CCQ ≥2 and <3, compared with CCQ total score <1. In the group without spirometry data (n = 440), after adjustment for age, sex, and heart disease, the HR was 2.32 (1.24 to 2.33) for CCQ total score ≥3, and 1.88 (0.98 to 3.60) for CCQ ≥2 and <3, compared with CCQ total score <1.

CCQ domain analyses and stratification by sex and age

Compared with CCQ <1, CCQ score ≥3 was statistically significantly and independently associated with mortality in all domains, and CCQ score ≥2 but <3 was associated with mortality in the mental and functional domains (Table 2). After further adjustment for lung function in the subset with spirometry data, statistically significant associations remained for CCQ score ≥2 but <3 and ≥3 in mental state and for CCQ ≥3 in functional state (data not shown). When entering the three different domains in a stepwise model, the functional domain remained as the most effective independent predictor of mortality. In addition, when the ten component items were entered separately in a stepwise model, the items that remained were all in the functional domain.

The adjusted HRs for the association of CCQ and mortality were higher in men than in women; however, interaction tests did not reveal statistically significant effect modification by sex (Table 3). No statistically significant interaction was found for age.

Table 3.

Stratification by sex

| Men (109 dead) HR (95%CI) adjusted* | Women (111 dead) HR (95%CI) adjusted* | |

|---|---|---|

| CCQ total score | ||

| <1 | Ref | Ref |

| ≥1, <2 | 1.95 (0.78 to 4.88) | 0.62 (0.30 to 1.26) |

| ≥2, <3 | 3.56 (1.47 to 8.63) | 1.40 (0.77 to 2.55) |

| ≥3 | 5.93 (2.53 to 13.9) | 2.15 (1.23 to 3.75) |

| CCQ score symptoms | ||

| <1 | Ref | Ref |

| ≥1, <2 | 1.41 (0.53 to 3.77) | 0.76 (0.38 to 1.51) |

| ≥2, <3 | 1.77 (0.68 to 4.59) | 1.00 (0.52 to 1.93) |

| ≥3 | 2.87 (1.14 to 7.21) | 1.62 (0.87 to 3.02) |

| CCQ score mental state | ||

| <1 | Ref | Ref |

| ≥1, <2 | 1.54 (0.77 to 3.06) | 1.12 (0.59 to 2.13) |

| ≥2, <3 | 2.33 (1.21 to 4.49) | 1.86 (1.01 to 3.41) |

| ≥3 | 3.45 (1.97 to 6.05) | 1.60 (0.94 to 2.72) |

| CCQ score functional state | ||

| <1 | Ref | Ref |

| ≥1, <2 | 2.17 (0.92 to 5.11) | 0.97 (0.48 to 1.93) |

| ≥2, <3 | 2.82 (1.26 to 6.31) | 1.37 (0.71 to 2.63) |

| ≥3 | 6.56 (3.09 to 13.9) | 2.86 (1.64 to 4.98) |

Note:

Adjusted for age and heart disease.

Abbreviations: CCQ, Clinical COPD Questionnaire; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

CCQ score and cause-specific mortality

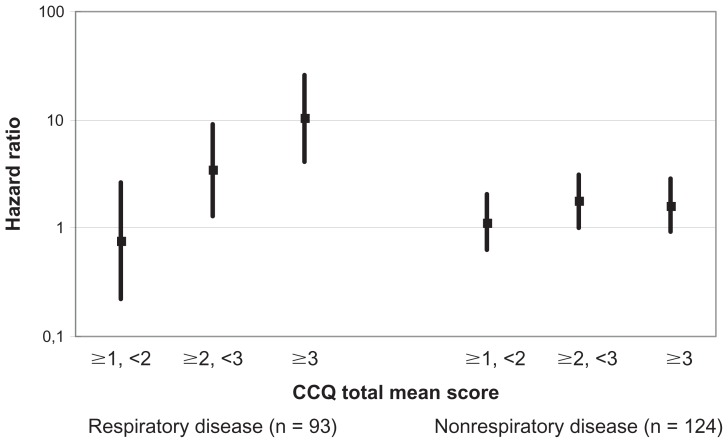

Cox regression analyses of cause-specific mortality showed that CCQ total score ≥3 and CCQ total score ≥2 but <3 were significantly and independently associated with an increased risk of respiratory disease–specific mortality. In the three remaining mortality groups, no associations were found for CCQ score with death due to cardiac disease, cancer, or other diseases (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

CCQ score and cause-specific mortality.

Note: Adjusted for sex and age.

Abbreviation: CCQ, Clinical COPD Questionnaire.

Treatment and vaccinations

Additional adjustment for treatment modalities, and influenza- or pneumococcal vaccination showed that the main results could not be explained by differences in treatment or vaccination status (data not shown).

SMR

Calculation of SMR showed that mortality was higher in the whole cohort, and in each group of total CCQ scores, than in the general Swedish population, particularly amongst those with the higher CCQ scores (Table 4).

Table 4.

Standardized mortality ratios for all-cause mortality

| O/E | SMR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| All | 220/64.3 | 3.42 (2.98 to 3.90) |

| CCQ total score | ||

| <1 | 23/12.3 | 1.87 (1.18 to 2.80) |

| ≥1, <2 | 34/18.6 | 1.83 (1.26 to 2.55) |

| ≥2, <3 | 29/16.2 | 3.64 (2.77 to 4.70) |

| ≥3 | 104/17.2 | 6.05 (4.94 to 7.33) |

Notes: O = Observed number of deaths; E = Expected number of deaths from the general population.

Abbreviations: CCQ, Clinical COPD Questionnaire; SMR, standardized mortality rates; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

The primary finding of this multicenter study of a clinical population including COPD patients from both primary and secondary care was that a higher CCQ total score, indicating lower health status, was independently associated with an increased mortality.

Previous studies have shown associations between HRQL estimated by extensive instruments and mortality,4–9 but to our knowledge, an association with mortality has not yet been demonstrated for the more convenient-to-measure CCQ score. In addition, all available studies of the St Georges Respiratory Questionnaire and mortality were performed in secondary care, and with the exception of only one study,7 all studies had exclusively or a very great majority of male participants. In this study, HRQL estimated by the CCQ predicted mortality independently of sex, age, and level of care.

The association between CCQ total score and mortality remained in the subgroup analysis of patients with available spirometry data, both before and after adjustment for lung function and the other potential confounding factors, so the results should not be explained by lung function alone. However, the hazard ratio was reduced after additional adjustment for lung function, indicating CCQ and lung function measures were related. The analysis of the association between CCQ and mortality in the patients with and without spirometry data showed a somewhat higher HR in those with spirometry data. Thus, even where spirometry data are available, a CCQ score adds predictive power for mortality.

The results of the domain analyses showed that the functional domain and the items it contained were the most effective predictors of mortality, probably because they are the most precise indicators of serious disease. The finding is consistent with a previous study of a shorter quality of life instrument (the Seattle Obstructive Lung Disease Questionnaire) where only the functional domain was associated with mortality.10

Men tended to have higher HRs than women for the association of CCQ total score with mortality. However, the interaction analysis showed that this difference was not statistically significant. The sex difference in the associations was not explained by differences in BMI or prevalence of depression, as further adjustment for BMI and depression did not alter the sex-specific associations notably.

SMR can be used to examine differences within a patient group, as was done in previous studies that compared relative mortality in different specific patient subgroups–smokers and nonsmokers with alpha-1-antitrypsin, and female COPD patients with long-term oxygen therapy.24,25 Not surprisingly, the analyses of SMR in our study showed that the patients with COPD had higher mortality than the general population. There was a striking dose-dependent association between CCQ score and mortality risk. This was found even in the group with low CCQ score; however, the ratios were higher with higher CCQ score. We found it interesting that our SMR analyses showed that the CCQ can be used to identify increased mortality even in COPD patients with stable health status and good HRQL.

The major strengths of this study are that it was longitudinal and that the study population was sampled from multiple centers representing both primary and secondary care. The data in medical records were initially recorded prospectively and should be reliable and not subject to recall bias. A limitation is that spirometry data were only available for a subgroup of patients. The fact that many COPD diagnoses are based on clinical findings rather than spirometry has been demonstrated previously.19 This could be due to an unwillingness to investigate what is considered a very likely diagnosis or, especially in primary care, resulting from a lack of confidence in the use and interpretation of spirometry results.26 This may have resulted in selection bias, which could potentially have influenced the results. However, the main findings remained both after additional adjustment for lung function and when comparing patients with and without spirometry data. Asthma is a common comorbid condition in this patient group, and sometimes it can be difficult to distinguish clinically between mild COPD and asthma. A subset of our study population had a diagnosis of both COPD and asthma, reflecting the clinical reality of a COPD population. However, comorbid asthma had little influence on the association of COPD with mortality, as indicated by our analyses that adjusted or stratified for asthma diagnoses. Using SMR may not have been the most precise way to estimate mortality, as the method could not take differences between the study and general population into account, other than for sex and age. However, this cannot explain the very high SMR among the patients with highest CCQ score, and the dose-dependent relationship cannot be explained by selection bias.

We conclude that the CCQ total score can be used as a prognostic instrument for mortality in COPD, and can identify a higher mortality risk than in the general population. This simple instrument provides information on both HRQL and mortality risk, both clinical measures of great importance in our COPD patients. Thus, the CCQ can be used to identify patients where interventions are most important.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grants from the county councils of the Uppsala-Örebro Health Care region, the Swedish Heart and Lung Association, the Swedish Asthma and Allergy Association, the Bror Hjerpstedts Foundation, and the Örebro Society of Medicine.

Thanks to Ulrike Spetz-Nyström and Eva Manell for reviewing the patient records, and to all participating centers.

Footnotes

Contributions

All coauthors have made substantial contributions to the conception of the study and editing of the manuscript. All of the coauthors have approved the submitted version of the paper.

Disclosure

The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest related to the material of the present study.

References

- 1.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. World Health Organization. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis. Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; NHLBI/WHO Workshop Report; 2001; Bethesda: National Institutes of Health; 2002. [Accessed May 24, 2012]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/Guidelines/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management-2001.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso J, Ferrer M, Gandek B, et al. IQOL Project Group. Health-related quality of life associated with chronic conditions in eight countries: results from the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Qual Life Res. 2004 Mar;13(2):283–298. doi: 10.1023/b:qure.0000018472.46236.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtis JR, Martin DP, Martin TR. Patient-assessed health outcomes in chronic lung disease: what are they, how do they help us, and where do we go from here? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(4 Pt 1):1032–1039. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.4.97-02011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domingo-Salvany A, Lamarca R, Ferrer M, et al. Health-related quality of life and mortality in male patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(5):680–685. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2112043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almagro P, Calbo E, Ochoa de Echagüen A, et al. Mortality after hospitalization for COPD. Chest. 2002;121(5):1441–1448. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oga T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, Sato S, Hajiro T. Analysis of the factors related to mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: role of exercise capacity and health status. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(4):544–549. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-583OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gudmundsson G, Gislason T, Lindberg E, et al. Mortality in COPD patients discharged from hospital: the role of treatment and co-morbidity. Respir Res. 2006;7:109. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halpin DM, Peterson S, Larsson TP, Calverley PM. Identifying COPD patients at increased risk of mortality: predictive value of clinical study baseline data. Respir Med. 2008;102(11):1615–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonelli-Incalzi R, Pedone C, Scarlata S, et al. Correlates of mortality in elderly COPD patients: focus on health-related quality of life. Respirology. 2009;14(1):98–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan VS, Curtis JR, Tu SP, McDonell MB, Fihn SD Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project Investigators. Using quality of life to predict hospitalization and mortality in patients with obstructive lung diseases. Chest. 2002;122(2):429–436. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Molen T, Willemse BW, Schokker S, ten Hacken NH, Postma DS, Juniper EF. Development, validity and responsiveness of the Clinical COPD Questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kocks JW, Tuinenga MG, Uil SM, van den Berg JW, Ståhl E, van der Molen T. Health status measurement in COPD: the minimal clinically important difference of the clinical COPD questionnaire. Respir Res. 2006;7:62. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kocks JW, Kerstjens HA, Snijders SL, et al. Health status in routine clinical practice: validity of the clinical COPD questionnaire at the individual patient level. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:135. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reda AA, Kotz D, Kocks JW, Wesseling G, van Schayck CP. Reliability and validity of the clinical COPD questionnaire and chronic respiratory questionnaire. Respir Med. 2010;104(11):1675–1682. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourbeau J, Ford G, Zackon H, Pinsky N, Lee J, Ruberto G. Impact on patients’ health status following early identification of a COPD exacerbation. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(5):907–913. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00166606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ställberg B, Selroos O, Vogelmeier C, Andersson E, Ekström T, Larsson K. Budesonide/formoterol as effective as prednisolone plus formoterol in acute exacerbations of COPD. A double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority, parallel-group, multicentre study. Respir Res. 2009;10:11. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundh J, Ställberg B, Lisspers K, Montgomery SM, Janson C. Co-morbidity, body mass index and quality of life in COPD using the Clinical COPD Questionnaire. COPD. 2011;8(3):173–181. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2011.560130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ställberg B, Lisspers K, Hasselgren M, Janson C, Johansson G, Svärdsudd K. Asthma control in primary care in Sweden: a comparison between 2001 and 2005. Prim Care Respir J. 2009;18(4):279–286. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2009.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arne M, Lisspers K, Ställberg B, et al. How often is diagnosis of COPD confirmed with spirometry? Respir Med. 2010;104(4):550–556. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quanjer PH, Tammeling GJ, Cotes JE, Pedersen OF, Peslin R, Yernault JC. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Report Working Party Standardization of Lung Function Tests, European Community for Steel and Coal. Official Statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J Suppl. 1993;16:5–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ställberg B, Nokela M, Ehrs PO, Hjemdal P, Jonsson EW. Validation of the clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) in primary care. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsiligianni G, Riemersma R, Price D, et al. Health status of COPD patients in clinical practice in three countries in Europe [Abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:A2855. [Google Scholar]

- 23.The statistic data base of the National Board of Health and Welfare. Sweden: [Accessed August 16, 2011]. Available from: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik/statistikdatabas. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanash HA, Nilsson PM, Nilsson JA, Piitulainen E. Survival in severe alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency (PiZZ) Respir Res. 2010;11:44. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ekström M, Franklin KA, Ström KE. Increased relative mortality in women with severe oxygen-dependent COPD. Chest. 2010;137(1):31–36. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolton CE, Ionescu AA, Edwards PH, Faulkner TA, Edwards SM, Shale DJ. Attaining a correct diagnosis of COPD in general practice. Respir Med. 2005;99(4):493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]