Abstract

Objective

To assess the limitations of the existing physician directory in measuring electronic health record adoption rates among a cohort of Connecticut physicians.

Design

A population-based mailing assessed the number of physicians practising in Connecticut.

Measurements

Information about practice site, practises pertaining to storing of patient information, sources of revenue and preferred method for receiving survey. Practice status in Connecticut, measured by yes and no. Demographic information was collected on gender, year of birth, race and ethnicity.

Results

The response rate for the postcard mailing was 19% (3105/16 462). Of the 16 462 unduplicated consumers, 233 (1%) were retired and 5828 (35%) did not practise in Connecticut. Of the 3105 valid postcard responses we received, 2159 were for physicians practising in Connecticut. Nine (0.4%) of these responses did not specify a preferred method for receiving the full physician survey; 91 physicians refused to participate in the survey; 2159 surveys were sent out using each physician's requested method for receiving the survey, that is, web-based, regular mail or telephone. As of August 2012, 898 physicians had returned surveys, resulting in a response rate of 42%.

Limitations

The postcard response rate based on the unduplicated lists adjusted for exclusions, such as death, retired and do not practise in Connecticut, is 30%, which is low. We may be missing physicians’ population which could greatly affect the indicators being used to measure change in electronic health record adoption rates.

Conclusions

It is difficult to obtain an accurate physician count of practising physicians in Connecticut from the existing lists. States that are participating in the projects funded under various Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) initiatives must focus on getting an accurate count of the physicians practising in their state, since their progress is being measured based on this key number.

Keywords: Physician Directory, Health Information Exchange, Evaluation of HIEs, Rate of EHR Adoption

Article summary.

Article focus

Addressing the challenges of measuring the rate of EHR adoption among physicians from state licence lists.

Key messages

Physician lists can be cleaned using simpler technologies and processes that do not require elaborate enterprise solutions.

States participating in the Health Information Exchange initiative need to ensure that they have valid and reliable baseline data, since this data will be used as a baseline to measure progress in the following years.

States must make an ongoing practice of maintaining clean lists of currently practising physicians.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study identifies a simple approach that states can undertake to clean their physician directories so that the baseline data used to calculate meaningful use measures is reliable. The study's limitation is its low response rate, which makes it more difficult for the state to estimate how many of its physicians will apply and attest successfully to receive payments under the electronic health record incentive programme. Cleaning of the physician list will need to be an ongoing process; every year new physicians are added to the existing list of licensed physicians, and some current physicians cease practising in the state. Cleaning the physician list is a manpower-intensive process that can include phone calls to confirm whether physicians are duplicated within the list, calls to confirm whether physicians still practise in the state, and on-line searches to correct invalid physician mailing addresses.

Introduction

The influx of American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 funding through the implementation of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act provides funds to small, privately owned primary care practices, federally qualified health centres, critical area access hospitals and other community health centres to implement and adopt health information technologies. These technologies include electronic health records (EHRs), e-prescribing systems and laboratory information systems. These funds were made available to all states through multiple initiatives, such as the Health Information Technology Extension Program, State Health Information Exchange (HIE) Cooperative Agreement Program and Community College Consortia to Educate Health Information Technology Professionals Program. Much has been written about the advantages of using HIEs and their resulting benefits of improving quality of care, patient safety and efficiency of delivering care.1–3

Background

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) has invested about $30 billion to implement the HITECH Act.4–7 The Health Information Technology Extension Program provides each state with funds to increase its physicians’ EHR adoption rate. Similarly, under the HIE programme, states are expected to build infrastructure and mechanisms that support the exchange of health information among physicians’ offices, hospitals, laboratories, pharmacies, registries and so on. The HIE initiative funds 56 Health Information Exchanges covering all states. One metric indicative of HIE success is the rate of change in the EHR adoption rate among physicians over the course of this 4-year initiative. This metric is linked to another outcome measure: the number of physicians who successfully demonstrate the exchange of summary documents with another provider, the state or a regional HIE. To this end, accurate data on practising physicians by state are needed. Data sources that list practising physicians in a state, however, are limited,8 since generating accurate lists of unduplicated physicians in a state is a labour-intensive activity. As a result, this indicator presents a challenge, since it assumes that there is an existing accurate list of the physician population that can be used to survey the physicians for EHR adoption rates. Establishing an accurate baseline list of physicians is important, since a progress on many health information technology (HIT) indicators would be based on the number of physicians that adopt and implement EHRs and other HIT practises. These physicians are eligible for incentives from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).9 Currently, many states realise that their physicians’ lists are inaccurate; this makes it difficult for them to calculate this basic measure of existing physicians who use certified EHRs.

In the first year of the HIE cooperative agreements, states have been working to establish a baseline for existing rates of EHR adoption. As part of this grant, ONC has established multiple communities of practise (CoP) targeting important performance outcome measures, including the e-prescribing CoP, the Lab CoP, Provider Directory CoP and the Security and Privacy CoP. The ‘Provider Directory CoP’ has been discussing the challenges associated with getting and subsequently maintaining an accurate list/directory of providers, which are related to the fact that physicians practise in multiple settings, change affiliations and may not practise in all states in which they hold licences.

In December 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released statewide results of EHR adoption rates, based on a mailed supplement to the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS).10 This supplement was started in 2008. The CDC study reports that 48% of office-based physicians use an EHR, 22% use a basic system and 7% use a fully functional EHR. These numbers are slightly higher than those reported in an earlier study, which reported 4% of the physicians as operating an extensive, fully functional electronic system, while 13% had a basic system.11

Currently, these data are the only state-level estimates available that systematically record EHR adoption rates. There are, however, two limitations that impact the NAMCS data's applicability and usefulness. First, the supplement questionnaire does not ask the key question about whether or not the EHR in use is certified.4 Second, the EHR adoption questions were asked at the practice level and not at the physician level. This distinction is important because the incentives which CMS is promoting are at the physician level and not at the practice level.

An HIE 2011 expert survey undertaken by CAQH and eHealth initiative to identify data elements needed to create provider directories, reported that provider directories are at the core of a successful exchange and need frequent updates. Additionally, they identified that health plans are the best source of provider information, followed by Medicaid offices and the providers themselves.12

Connecticut Health Information Exchange Landscape

The Health Information Technology Exchange of Connecticut (HITE-CT), a quasi-public agency, was created by the Public Act 10-117, An Act Concerning Revisions to Public Health-Related Statutes and the Establishment of the Health Information Technology Exchange of Connecticut, Sec. 82-90,96 (codified at CGS §19a-750(c)1,13 by the 2010 Connecticut General Assembly and Governor Rell. It is managed by an appointed Board of Directors who held their first meeting in October 2010 to coordinate and oversee Health Information Exchange (HIE) activities starting in 1 January 2011. Each board member represents a constituent stakeholder group, such as consumer or consumer advocates, primary care physicians, pharmacists, employer and/or business groups.

According to NAMCS estimates for Connecticut, 48% of office-based physicians use an EHR and 15% report having a basic EHR system,10 whereas another recent evaluation study puts this number at 36%.14 This paper addresses the challenges of measuring the rate of EHR adoption among physicians on this list.

Methods

Data

The Connecticut Department of Public Health contracted with the University of Connecticut Health Center (UCHC) to evaluate its Health Information Technology and Exchange (HITE) Cooperative Agreement, funded by the ONC. The contract period for this evaluation is 7/1/2010–3/14/2014. This evaluation uses mixed methods, namely, survey research and in-depth interviews. A family of surveys is being undertaken to measure Connecticut-HITE's impact, such as physician EHR adoption rate, e-prescribing practises, laboratory readiness for interoperability and states an ability to sustain this effort after the federal funds are expended. All studies were reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at UCHC.

For the physician survey implementation, the evaluators received a list from the Department of Public Health (DPH), which issues licences of practise to physicians, generated a list of 16 618 physicians in May 2011 and another list of 5283 physicians from the Department of Social Services Medicaid physician list. No phone numbers or e-mail addresses were available on this list. These lists were combined and after deleting duplicates the final list included a cohort of 18 642 physicians.

Members of the board of directors of HITE-Connecticut believed that there were about 8000 physicians actively practising in Connecticut. Owing to the discrepancy between the actual list and the number of physicians believed to be practising in Connecticut, a two-step survey process was implemented to ascertain the list's accuracy. First, a postcard was mailed to all the physicians on the list. Second, surveys were mailed to physicians who responded to the postcard, to assess physicians’ use of EHRs; their opinions about their EHR's utility; their familiarity with HIE and their opinions about barriers and incentives that may impact HIE implementation. This paper discusses the responses to the postcard.

Postcard survey instrument

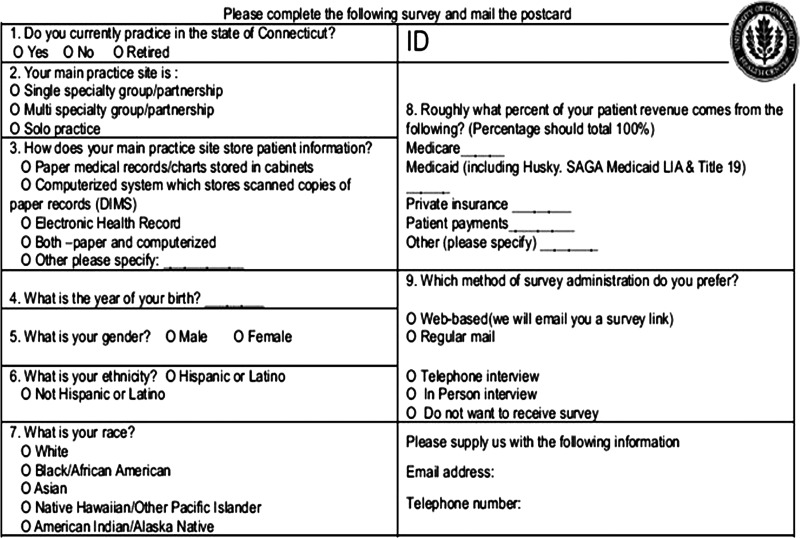

The postcard asked 10 questions. These questions included whether the person practised in Connecticut, age, race, ethnicity, gender, practice site, methods used to store medical record data, sources of patient revenue and preferred methods for receiving the subsequent survey. Figure 1 contains a picture of the postcard.

Figure 1.

Postcard questions.

Postcard administration

Every licensed physician who was on the list as of May 2011 was mailed a postcard through the US postal system. A total of 18 642 postcards were mailed.

Analysis

Responses to the postcard mailing were analysed using SQL and SPSS.

Results

We received 4104 of the 18 642 postcards that were mailed. Of these, 999 were returned undelivered; 9 respondents practised in Connecticut but did not choose a preferred method for receiving a survey; and 2159 were valid addresses with an identified method for receiving the physician survey. Additionally, 10 postcards were returned with a note that the physician had received two postcards. This led us to review the list closely for duplicate physicians. To do this, we systematically used the internet to search for telephone numbers for practices containing possible duplicate physicians, and we then called these practices to confirm that the physician on our list was still practising at the address listed. Between the mailing and telephone calls to practices, 2180 were identified as duplicates, 233 physicians were identified as having retired, and 5828 were identified as not practising in Connecticut. A second mailing of 713 postcards was completed in November 2011 with updated addresses for postcards that were returned to us as undelivered from the first mailing. A subsequent third mailing was completed in March 2012 to 6496 non-respondents from the first list. A fourth postcard mailed in May 2012 reached 117 physicians whose postcards from the third mailing had been returned as undeliverable.

Response rate

The overall postcard response rate was 19%. Of the 16 462 unduplicated physicians in the master list, 44 had died, 233 were retired, 5828 no longer practised in Connecticut and 30 did not specify whether they practised in Connecticut. This left an adjusted target population of 10 327 physicians; the response rate for this target population was 30%. Table 1 provides the results from the process undertaken to clean the master physician list.

Table 1.

Cleaning physician list

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Physician list received from CT-DPH | 18 642 | |

| Duplicates in the list | 2056 | |

| Triplicates in the list | 100 | |

| Quadruplicates in the list | 12 | |

| Quintuplicates in the list | 12 | |

| Unduplicated Physician list | 16 462 | |

| Responses to the Physician postcard | ||

| No response | 12 358 | 75.1 |

| Postcard returned because of invalid address | 999 | 6.1 |

| Postcard returned completed | 3105 | 18.9 |

| Physicians excluded because of death, retirement, etc | ||

| Died | 44 | 0.3 |

| Retired | 233 | 1.4 |

| No Longer practises in CT | 5828 | 35.4 |

| Postcard returned: unknown if physician practises in CT | 30 | 0.2 |

| Target population after exclusions | 10 327 | |

| Adjusted postcard response rate based on target population | 30.1 | |

| Physicians receiving full survey | ||

| Refused to participate in the survey | 91 | |

| Postcard returned; no preferred survey method specified; unable to contact physician to get a preferred method | 9 | |

| Physician practices in CT; survey sent | 2159 | |

| Response rate for survey | 898 | 41.6 |

Characteristics of respondents

The age of the physicians ranged from 28–91 years, representing a mean age of 55 years and an SD of 12 years. Sixty-eight per cent of the respondents were men and 31% were women. Eighty-three per cent of the physicians selected white, while 11% selected Asian and 3% selected black as their race. Only 3% of the respondents were of a Hispanic origin.

Characteristics of the practice site

Most physicians (53%) reported practising in a single-specialty group practice, 23% of the physicians practised in a multispecialty group practice, and 20% had a solo practice.

Handling of patient records

Most physicians (36%) reported using only paper records; 29% reported using a combination of paper and computerised records; 27% were using EHRs; 4% were using scanned images of paper records and 3% were in the process of moving to an EHR.

Source of patient revenue

When asked about income, 43% reported that more than 30% of their revenue came from Medicare; 18% reported that more than 30% of their revenue came from Medicaid; 67% reported that more than 30% of their revenue came from private insurance and about 7% reported more than 30% of their revenue came from patient payments.

Selection of method for survey administration

A majority (56%) of the physicians wanted to receive their survey through the mail, while 40% preferred the web-based survey. Demographic and sample characteristics are summarised in table 2.

Table 2.

Demographics and other sample characteristics

| n=2159 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 55 years (SD 12) | |

| Range | 28–91 years | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1460 | 67.6 |

| Female | 659 | 30.5 |

| Missing | 40 | 1.9 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino origin | 74 | 3.4 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 2017 | 93.4 |

| Missing | 68 | 3.1 |

| Race | ||

| White | 1784 | 82.6 |

| African–American | 55 | 2.5 |

| Asian | 228 | 10.6 |

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific islander | 12 | 0.6 |

| American Indian | 3 | 0.1 |

| Multiple races | 0 | 0.0 |

| Missing | 77 | 3.6 |

| Practice type | ||

| Solo practice | 433 | 19.7 |

| Single speciality group | 1141 | 52.8 |

| Multi-speciality group | 495 | 22.6 |

| Did not respond | 90 | 4.2 |

| How does your main practice site store patient information | ||

| Paper medical records/charts stored in cabinets | 771 | 35.7 |

| Both—paper and computerised | 621 | 28.8 |

| Electronic health record | 582 | 27.0 |

| Computerised system which stores scanned copies of paper records (DIMS) | 94 | 4.4 |

| Other | 48 | 2.2 |

| Multiple storage methods | 30 | 1.4 |

| Missing | 13 | 0.6 |

| Percentage of patient revenue, Medicare | ||

| None | 95 | 4.4 |

| Less than 30 | 563 | 26.1 |

| More than 30 | 932 | 43.2 |

| Missing | 569 | 26.4 |

| Percentage of patient revenue, Medicaid | ||

| None | 138 | 6.4 |

| Less than 30 | 1031 | 47.7 |

| More than 30 | 390 | 18.1 |

| Missing | 600 | 27.8 |

| Percentage of patient revenue, private insurance | ||

| None | 14 | 0.6 |

| Less than 30 | 358 | 16.6 |

| More than 30 | 1437 | 66.6 |

| Missing | 350 | 16.2 |

| Percentage of patient revenue, patient payments | ||

| None | 23 | 1.1 |

| Less than 30 | 1204 | 55.8 |

| More than 30 | 146 | 6.8 |

| Missing | 786 | 36.4 |

| Percentage of patient revenue, other | ||

| None | 36 | 1.7 |

| Less than 30 | 151 | 7.0 |

| More than 30 | 82 | 3.8 |

| Missing | 1890 | 87.5 |

| Preferred method of survey administration | ||

| Web-based | 855 | 39.6 |

| Regular mail | 1198 | 55.5 |

| Telephone interview | 21 | 1.0 |

| In-person interview | 12 | 0.6 |

| Multiple | 16 | 0.7 |

| Missing | 57 | 2.6 |

DIMS, data information management system.

Discussion

The physician list was inadequate for the purpose of administering the survey as indicated by the difference between our start-up count of 18 642 and the final adjusted count of 10 327. DPH licences physicians to practise in Connecticut but does not maintain a list of practising physicians. We found that physicians move, retire, graduate from medical school and die. Any one of these issues by itself does not create a lot of noise, but together, these issues render the list a suspect for calculating outcome measures. At any given time, it is difficult for the DPH or any other body to know who is practising in the state of Connecticut. This issue is being identified as a challenge across states.12 As work is being done to set up health information and health insurance exchanges, accurate provider directories are the first step in setting up functional exchanges for health provision and coordination.

Currently, DPH uses both electronic and paper processes for licence renewal. We recommend that the state licensing and renewal application add two questions that may improve the list substantially over a period of 1 year, given that all physicians have to renew their licences annually. First, physicians should be asked whether they practise in the state. Second, it may be useful to have all physicians designate the sites at which they practise; these sites should be flagged as either primary or secondary sites. This is important because, even though physicians may practise at multiple sites, we want them to respond to our survey based on their experience at their primary site. Third, it may be time to mandate that all renewals be done electronically; this would eliminate the process of merging the two sources of license renewal data to obtain a master list. Last, a subset of these physicians will be applying to CMS for incentives. As a result, the projected number of physicians who are likely to apply for these incentives could be off by a significant magnitude.

There has been a pressure on the states that received HIE grants to document baseline EHR adoption rates quickly. This may not be feasible, given that it took a year to get the survey out into the field and then realise that the list was not accurate. We were concurrently cleaning the list as we were sending surveys out to physicians. It would have been more prudent to first clean the list and then send out postcards. Also, ONC would be better-off allowing states to use the rates estimated by NAMCS as their baselines; this would allow states the necessary time to get their provider directories in order and to then implement a statewide physician survey based on the population or a sample to measure change overtime in EHR adoption rates.

Last, we feel that the two-step approach, using a postcard followed by a survey, is prudent in two ways. First, we would have wasted a lot of our funds had we just mailed out our survey at a cost of $1 per survey in comparison to 25 cents per postcard. Second, we were surprised that 56% of the respondents preferred a regular mail to web-based surveys. Given that most surveys with physicians are done using the internet, we would have lost a lot of responses had we only used the web-based method for survey administration.

Limitations

The postcard response rate is a challenge as the state tries to estimate how many of its physicians would apply and attest successfully to receive incentive payments from CMS. The evaluation team called the practises in the list to identify possible duplicates, since at least 50% of the physicians indicate that they practise at more than one site. Cleaning up of the physician list needs to be an ongoing process, since every year, new physicians are added to the existing list of licensed physicians. It is possible that the question about ‘revenue sources (Q8)’ may have depressed the response rate, since physicians may have perceived this as a ‘Big Brother’-style question. It is possible that the physicians feel ‘survey fatigue’ or that they did not want to respond to this survey. We believe that asking these questions on a licence-renewal application may yield better results, since every physician in the state has to renew their license annually. Also, it is possible that respondents who chose ‘no’ or ‘retired’ to the first question did not return the survey as we did not have clear skip instructions asking them to return the survey even if they only answered Q1.

Conclusion

It is extremely difficult for states that do not have a centralised provider directory to maintain an accurate list of practising providers. For such states, the environment scan data incorporated in the statewide strategic and operational plan submitted to the ONC may have some errors and limitations. Even though they might be the best baseline data available at the state level, ONC will need to be cautious in using this indicator, since the effort to clean the physician list is up to the state. Measuring the progress on the EHR adoption indicator can be accurate only if all states use a systematic process for cleaning their lists of practising physicians. In the state of Connecticut, we were able to remove duplicates from the list using a simple process of checking the internet, followed by calls to doctors’ offices. Other states may want to follow this simple process if they do not have the funds available to buy systems and hire staff whose sole responsibility would be to clean their physician list. As a result, each list's accuracy would vary proportionally to the time and resources spent on cleaning the list.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge Michael J Hettinger for the analysis of this data, Deborah Steciak, Holly Roy and Estherline Thoby for cleaning of the physician list. I would like to thank Kathryn Pyle Krages, AMLS, MA, Assistant Professor, Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, Oregon Health Sciences University for reviewing the paper and providing comments for improvement.

Footnotes

Contributors: MT is the sole author of this paper.

Funding: This work was supported by award number 90HT0043/01 from the ONC.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: UCHC IRB.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Wright A, Soran C, Jenter CA, et al. Physician attitudes toward health information exchange: Results of a statewide survey. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2010;17:66–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vest JR, Zhao H, Jaspserson J, et al. Factors motivating and affecting health information exchange usage. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:143–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adler-Milstein J, Bates DW, Jha AK. A survey of health information exchange organizations in the United States: implications for meaningful use. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:666–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health information technology: initial set of standards, implementation specifications, and certification criteria for electronic health record technology Interim final rule. Fed Regist 2010;75:2013–2047 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenthal D. Stimulating the adoption of health information technology. W V Med J 2009;105:28–29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumenthal D, Tavenner M. The ‘meaningful use’ regulation for electronic health records. N Engl J Med 2010;363:501–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumenthal D. Launching HITECH. N Engl J Med 2010;362:382–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jha AK, Doolan D, Grandt D, et al. The use of health information technology in seven nations. Int J Med Inf 2008;77:848–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services The official web-site for the Medicare and Medicaid EHR Incentive Program. http://www.cms.gov/EHRIncentivePrograms/01_Overview.asp#TopOfPage (accessed 20 Nov 2010)

- 10.Hsiao CJ, Beatty PC, Hing E, et al. Electronic medical record/electronic health record systems of office-based physicians: United States, 2009 and preliminary 2010. December 2010; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/emr_ehr_09/emr_ehr_09.pdf (accessed 14 Nov 2011) [PubMed]

- 11.DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Rao SR, et al. Electronic health records in ambulatory care—A national survey of physicians. N Engl J Med 2008;359:50–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CAQH and eHealth Initiative. http://www.caqh.org/Host/UPD/Survey_CAQH and eHealth Initiative: Health Information Exchange (HIE) and Provider Directory Survey Results HIEProviderDirectory.pdf (accessed 31 Aug 2012)

- 13.State of Connecticut. Substitute Senate Bill No. 428, Public Act No. 10–117, An act concerning revisions to public health related statues and the establishment of health information technology exchange of Connecticut (accessed 8 Dec 2011)

- 14.Tikoo M. Connecticut's Health Information Technology Exchange Evaluation Process: baseline assessments & updates, http://www.cicats.uconn.edu/pdf/bmi/HITECT-Report.pdf (accessed 8 Dec 2011)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.