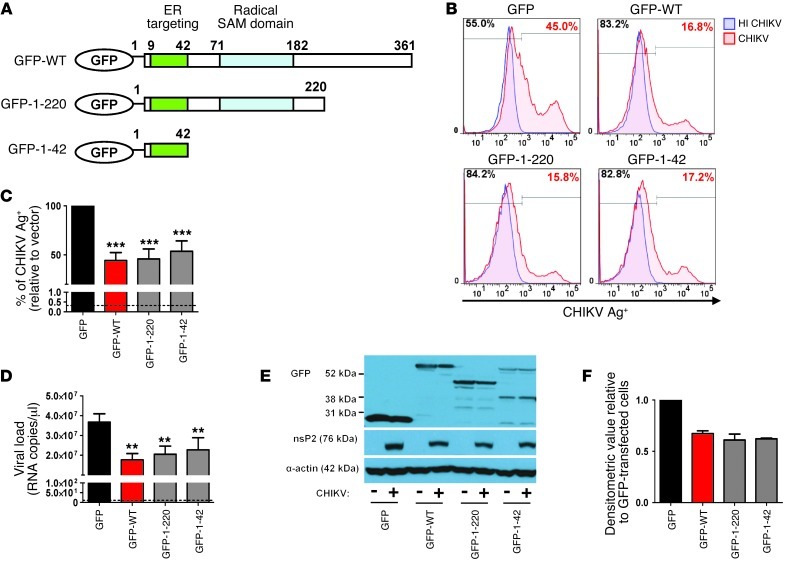

Figure 4. The N-terminal amphipathic α-helical domain of viperin controls CHIKV replication.

(A) Schematic representation of the domain organization of GFP–WT viperin (GFP-WT), the GFP–N-terminal α-helical domain of viperin (GFP-1-42), and another GFP-tagged viperin mutant with both the N-terminal amphipathic α-helical and radical SAM domains (GFP-1-220). (B) HEK 293T cells were transfected with the various plasmids for 24 hours before infection with either HI CHIKV (control) or CHIKV at MOI 2.5. Cells were analyzed for CHIKV infectivity as described in Figure 3B. Histogram plots of percent CHIKV Ag+ cells in the indicated cell populations are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Graphical presentation of histogram plots in B. Data are mean ± SD of percent CHIKV Ag+ cells relative to vector-transfected cells infected with CHIKV (n = 3). ***P < 0.001, 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. Horizontal dotted line represents the mean percent CHIKV Ag+ cells in controls. (D) Viral load was determined by qRT-PCR as described in Figure 3D. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.01, 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. Horizontal dotted line represents the mean amount of RNA detected in controls. (E) Viperin expression was detected with anti-GFP antibody. CHIKV nsP2 expression in the infected cells was detected with anti-nsP2 antibody. Detection of α-actin expression served as a loading control. Immunoblots are representative of 2 independent experiments. (F) Densitometric analysis of the nsP2 band in E was performed with NIH ImageJ software and normalized against actin band before being expressed relative to GFP-transfected cells.