Abstract

Silicon (Si) cycling controls atmospheric CO2 concentrations and thus, the global climate, through three well-recognized means: chemical weathering of mineral silicates, occlusion of carbon (C) to soil phytoliths, and the oceanic biological Si pump. In the latter, oceanic diatoms directly sequester 25.8 Gton C yr−1, accounting for 43% of the total oceanic net primary production (NPP). However, another important link between C and Si cycling remains largely ignored, specifically the role of Si in terrestrial NPP. Here we show that 55% of terrestrial NPP (33 Gton C yr−1) is due to active Si-accumulating vegetation, on par with the amount of C sequestered annually via marine diatoms. Our results suggest that similar to oceanic diatoms, the biological Si cycle of land plants also controls atmospheric CO2 levels. In addition, we provide the first estimates of Si fixed in terrestrial vegetation by major global biome type, highlighting the ecosystems of most dynamic Si fixation. Projected global land use change will convert forests to agricultural lands, increasing the fixation of Si by land plants, and the magnitude of the terrestrial Si pump.

Introduction

Global silicon (Si) cycling regulates atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations via several well-known mechanisms, particularly chemical weathering of mineral silicates [1], occlusion of carbon (C) to soil phytoliths [2], and the oceanic biological Si pump [3]. The vast majority of research on Si cycling has focused on the oceans, where Si-replete diatoms sequester 240 Tmol Si yr−1 [4]. Diatoms are also a critical component of the global C cycle, accounting for 35–75% of marine net primary production (NPP) [4] and serving as efficient exporters of C to the benthos [5].

However, similar to diatoms, terrestrial vegetation can also sequester large amounts of Si. Si is considered a ‘quasi-essential’ nutrient for plants [6]. While most plants can grow in Si-deplete soils, plant fitness is markedly improved with Si amendments [7]. In fact, Si is the only element that has been shown to never be toxic to plants even in high doses [7]. Silicon protects plants from a variety of abiotic and biotic stresses, including desiccation, predation, fungal attack, and heavy metal toxicity [6]–[8]. Ultimately, Si plays a critical role in plant defense [6], which we argue better facilitates plants to perform essential services, particularly C sequestration.

Si concentrations in land plants range over two orders of magnitude (<0.1 to over 10% by dry weight (by wt.)), the largest range of any element [6]. All photosynthetic plants contain some Si within their tissue, often in concentrations equal to or greater than other macronutrients, such as nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) [8]. Plants are typically broken into three modes of Si uptake: rejective, passive accumulators, or active accumulators [7]. Plants whose Si uptake is greater than that which would passively be taken up through the transpiration stream are defined as active accumulators and typically contain >0.46% Si (or 1% SiO2) by wt. [7], [9], [10].

Plants take up dissolved silica (DSi) (H4SiO4) from soil solution via their roots. DSi is transported via the xylem for eventual deposition in transpiration termini. Upon incorporation into organisms, biogenic silica (BSi) is formed, creating siliceous bodies in cell walls known as phytoliths. While the ultimate source of Si in the biosphere is chemical weathering of mineral silicates, BSi is 7 to 20 times more soluble than mineral silicates [11], resulting in BSi being an important source of DSi on biological time scales [12]. The dynamic cycling of Si on its path from land to sea has only recently been documented [11], [13], demonstrating that the biological component of the global Si cycle is driven not only by diatoms, but also by terrestrial organisms [14].

To date, the amount of Si fixed by land plants has only been estimated at the global scale [13], [15], never by major terrestrial ecosystem type. Because certain plants, such as grasses, fix more Si than others, fixation of Si on land is far from uniform. Thus, we distinguish the hot spots of Si fixation, by calculating the amount of Si fixed by biome type (Table 1). Using this information, we calculate the percentage of terrestrial NPP done via active-Si accumulating organisms. To do this, we categorized Si shoot/leaf concentrations of 32 orders of angiosperms, gymnosperms, and mosses into 11 biome categories. Taxonomic order was chosen to categorize plants, as it accounts for the majority (67%) of the variability of Si concentrations within plant tissue [16].

Table 1. Amount of Si fixed by major biome type. Bold indicates on average, active Si accumulation, indicated by concentrations >0.46% Si by wt. [7].

| Biome Type | NPP (C)×103(Tmol yr−1) | Avg %Siby wt. | Si:C | Si(Tmol yr−1) | |

| Tropical wet andmoist forest | 0.69 | 0.30 | 0.006 | 4.48 | |

| Tropical dry forest | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.006 | 2.35 | |

| Temperate forest | 0.50 | 0.21 | 0.004 | 2.22 | |

| Boreal forest | 0.53 | 0.23 | 0.005 | 2.65 | |

| Tropical woodlandand savanna | 0.93 | 1.13 | 0.024 | 22.19 | |

| Temperate steppe | 0.41 | 1.53 | 0.032 | 13.26 | |

| Desert | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.006 | 0.65 | |

| Tundra | 0.12 | 1.07 | 0.023 | 2.66 | |

| Wetland | 0.32 | 0.62 | 0.013 | 4.16 | |

| Cultivated land | 1.01 | 1.37 | 0.029 | 29.41 | |

| Rock and ice | 0 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0 | |

| Average | 0.64 | 0.014 | |||

| Total | 5.02 | 84.03 | |||

| Std Dev | 0.32 | 0.006 | 28.86 | ||

Materials and Methods

Leaf tissue Si concentrations were taken from supplemental data assembled in the meta-analysis completed by Hodson et al. (2005). From this dataset, 32 orders of angiosperms, gymnosperms, and mosses (representing 528 species) were assigned to a specific biome type. Fifteen orders fell into two different biome types (e.g. Pinales – temperate and boreal forest biomes). The order Poales (i.e. grasses, sedges, and rice) was the only order that fell into more than two biome types.

Given that average C concentrations in biomass consistently range from 45 to 50% [17], we assumed a wood C concentration of 47%. Dividing the calculated biome-specific average Si concentrations by 47% allowed us to calculate Si:C ratios for each biome (Table 1). In turn, our biome-specific Si:C ratios were multiplied by the known amount of C in each biome [17], creating a constrained estimate of the Si fixed by ecosystem type (Table 1).

Error estimates for the four forest biomes and the wetland biome were calculated by taking the standard deviation of the Si concentrations in the leaf/shoot tissue. Average Si concentration of the ‘tropical woodland and savanna’ biome was weighted for vegetation type (grasses accounted for 70%, herbaceous shrubs and trees accounted for 30% [18]). Error estimates associated with this biome include a sensitivity analysis of ±20% of each plant type. Likewise, average Si concentration of cultivated crops was weighted to account for the mass of the top four crops produced in 2010 [19] (Table 2). Average Si concentration of the tundra biome used an non-weighted average of the Poales (sedges), Sphagnales (mosses), and Ericales (herbaceous shrubs) orders. Average Si concentration of the temperate steppe biome included only Poales (grasses) as the predominant vegetation type.

Table 2. Average Si concentration of cultivated crop biome, weighted by the mass of the four most produced crops [19].

| Order | Genus | % Siby wt | Mass of Crop(Million Tons) | Si(Million tons) |

| Poales | Saccharum | 0.54 | 1685 | 910 |

| Poales | Triticum | 2.42 | 650 | 1573 |

| Poales | Zea | 0.79 | 844 | 667 |

| Poales | Oryza | 3.17 | 672 | 2130 |

| Total | 3851 | 5280 | ||

| Average Si concentration | 1.37 | |||

Si fixed through land use change via increased agriculture was calculated by creating a correction factor that accounted for changes in land area of biome categories [20]. Correction factors were multiplied by the amount of Si currently fixed in each biome category in order to estimate the amount of Si fixed by 2050.

Results

The amount of Si fixed annually by the 11 major biome types found on Earth was calculated (Table 1). Unsurprisingly, the least amount of Si was found in the rock and ice, and desert biomes (<1 Tmol yr−1). Cultivated lands contain more Si than any other biome (29 Tmol yr−1), due to both high average Si content of the most common cultivated crops (Table 2) and the large amount of biomass present on cultivated lands (Tables 1, 2).

While Si typically is deposited in the foliage, or leaves of trees, wood can also contain appreciable amounts of Si. Tropical forests contain relatively high levels of Si within their wood (Avg. 0.31% by wt.) [21], [22], roughly four times more than the wood of temperate and boreal forests (Avg. 0.08% by wt.) [23]. In order to account for the different allocation of Si within various components of forest ecosystems, forest biome average Si concentrations were weighted to account for 30% of forest NPP being attributed to foliage, with the remainder allocated to woody biomass [24].

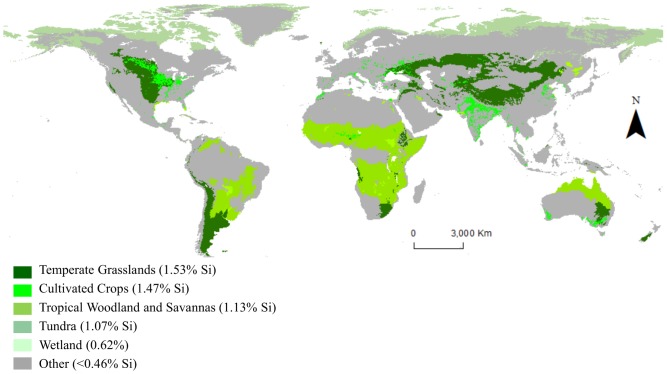

Active Si accumulation, indicated by average Si concentrations >0.46% by wt., was observed in five biomes: tropical woodland and savanna, temperate steppe, tundra, wetland, and cultivated lands (Figure 1). The elevated concentrations in these biomes were driven mostly by the predominance of the order Poales (e.g. grasses, sedges, and rice). These five biomes, which exhibit active Si accumulation, account for 55% of terrestrial NPP (Table 1). Thus, we conclude that just over half of terrestrial NPP is done by active-Si accumulating organisms, rivaling that of oceanic phytoplankton [17]. Combining our results with the estimate that 43% of ocean NPP is via Si-replete diatoms [4], we find that 59 Gton C yr−1, or 49%, of current global NPP is conducted by active Si-accumulating organisms.

Figure 1. Global land cover by Si accumulating crops.

Shades of green are directly proportional to degree of active Si accumulation (i.e., darker green indicates more Si accumulation). Gray area indicates land cover by biomes of non-active Si accumulators (<0.46% Si by dry wt.) (Table 1). Data from combination of FAO GeoNetwork Global Land Cover Distribution 2007 raster data layer with a resolution of 5-arc minutes, and ESRI, which modified the layer originally created by Olson et al. (2001). Map created using ArcMap 10.0 from ESRI.

In order to provide a check of our results, we compared our total amount of Si fixed by land plants with those from previous studies. Summing our values of Si fixed by biome type, we find that 55–113 Tmol Si yr−1 is fixed globally in the terrestrial biosphere (Avg. 84±29 Tmol Si yr−1). Our value is within the bounds of that provided by Conley (2002) (60–200 Tmol yr−1) and almost identical to the global estimate provide by Laruelle et al. (1999) (80 Tmol yr−1), providing confidence in our estimates.

Discussion

Human activities have already altered the amount of Si fixed in aquatic ecosystems. At the same time that the fluxes of N and P to coastal systems have markedly increased [25], river damming has led to significant declines in the amount of Si exported to coastal waters [26]. Combined, these two factors have increased the concentrations of N and P relative to Si, altering the ratio of N:P:Si in marine waters and inducing Si-limitation in several systems [27]–[29]. Such Si-limiting conditions can shift the phytoplankton species composition from diatom to non-diatom species, altering the base of the marine tropic structure [30], [31]. Importantly, because diatoms are more efficient C exporters compared to other types of phytoplankton [5], shifting phytoplankton community structure away from diatoms reduces the amount of C exported to the benthos via the ocean biological pump.

Similarly, we hypothesize that land use change will also alter the magnitude of Si fixed in the terrestrial biosphere, although in the opposite direction. Because both cultivated crops and pasture land (included in grasslands) are the biomes of most Si sequestration, increases in agricultural production will increase the amount of BSi fixed by land plants. Our analysis shows that cultivated crop lands currently account for 35% of the BSi fixed on land each year. Area of crop and pasture land is projected to increase by 8.9×106 km2, or 18%, by 2050 [20]. Assuming conversion of tropical forests to agricultural land, we calculate that an additional 7.5 Tmol Si yr−1 will be fixed by 2050, an increase of 9% from current levels. Thus, increased food production to feed a larger global population will heighten the magnitude of the terrestrial Si pump, as more BSi will be produced on land.

Because the Si fixed via crop cultivation is transported around the globe in large quantities, agriculture has recently been highlighted as an overlooked component of the global biological Si cycle [32]. Ultimately, much of the BSi stored in crops will be transferred to human population centers, or urban areas, which have been shown to export more Si than their forested counterparts [33]. The heightened production of the more-soluble biogenic Si within the biosphere may increase the capacity of urban systems to serve as sources of Si to coastal waters [34]. In turn, it is possible that Si-limiting conditions downstream of urban centers are buffered by the terrestrial Si pump and not as high as they would be in its absence. We hypothesize that additional Si fluxes from urban centers have the potential to improve the balance to N:P:Si ratios, at least in part, mitigating Si-limitation of nutrient-rich receiving waters.

However, the fate of the cultivated and harvest BSi in crops deserves further research attention, as environmental management practices, such as wastewater treatment, sludge disposal, and farming techniques will ultimately dictate the fate of the additional BSi produced by land plants [32]. In addition, the storage of sediment BSi and subsequent release as DSi are not directly connected processes, as they can occur over variable periods of time [35]. Soil pools contain at least two orders of magnitude more BSi than vegetation pools [13], highlighting that much of the BSi produced on land will be stored in the soils, rather than exported directly via rivers. While agricultural production will increase the amount of Si fixed by land plants, centuries of continual crop harvests have been shown to deplete soil pools of BSi [32], [35], [36]. Thus, conversion of more land for agricultural production could deplete soil BSi reserves over time, which could ultimately impact the magnitude of the terrestrial Si pump and long-term fluxes of Si to coastal systems.

Funding Statement

This research was partially developed under STAR Fellowship Assistance Agreement no. FP917238 awarded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to J.C. Carey. It has not been formally reviewed by EPA. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of J.C. Carey and R.W. Fulweiler, and EPA does not endorse any products or commercial services mentioned in this publication. In addition, this research was conducted under an award from the Estuarine Reserves Division, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, National Ocean Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to J.C. Carey. The authors would also like to thank the Department of Earth Sciences at Boston University for partial funding support of J.C Carey. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Berner RA, Lasaga AC, Garrels RM (1983) The carbonate-silicate geochemical cycle and its effect on atmospheric carbon dioxide over the past 100 million years. American Journal of Science 283: 641–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Parr JF, Sullivan LA (2005) Soil carbon sequestration in phytoliths. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 37: 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dugdale RC, Wilkerson FP, Minas HJ (1995) The role of a silicate pump in driving new production. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 42: 697–719. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tréguer P, Nelson DM, Van Bennekom AJ, DeMaster DJ, Leynaert A, et al. (1995) The silica balance in the world ocean: A re-estimate. Science 268: 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ittekkot V, Humborg C, SchÄFer P (2000) Hydrological Alterations and Marine Biogeochemistry: A Silicate Issue? BioScience 50: 776–782. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Epstein E (2009) Silicon: its manifold roles in plants. Annals of Applied Biology 155: 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma JF, Miyake Y, Takahashi E (2001) Chapter 2: Silicon as a beneficial element for crop plants. In: Datnoff LE, Snyder GH, Korndörfer GH, editors. Studies in Plant Science: Elsevier. 17–39.

- 8. Epstein E (1994) The anomaly of silicon in plant biology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 91: 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hou L, Liu M, Yang Y, Ou D, Lin X, et al. (2010) Biogenic silica in intertidal marsh plants and associated sediments of the Yangtze Estuary. Journal of Environmental Sciences 22: 374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Street-Perrott FA, Barker PA (2008) Biogenic silica: a neglected component of the coupled global continental biogeochemical cycles of carbon and silicon. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 33: 1436–1457. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cornelis J-T, Delvaux B, Georg RB, Lucas Y, Ranger J, et al. (2010) Tracing the origin of dissolved silicon transferred from various soil-plant systems towards rivers: a review. Biogeosciences Discuss 7: 5873–5930. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Derry LA, Kurtz AC, Ziegler K, Chadwick OA (2005) Biological control of terrestrial silica cycling and export fluxes to watersheds. Nature 433: 728–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Conley DJ (2002) Terrestrial ecosystems and the global biogeochemical silica cycle. Global Biogeochem Cycles 16: 1121 DOI: 10.1029/2002gb001894. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carey JC, Fulweiler RW (2012) Watershed land use alters riverine silica cycling. Biogeochemistry. DOI: 10.1007/s10533-012-9784-2.

- 15. Laruelle GG, Roubeix V, Sferratore A, Brodherr B, Ciuffa D, et al. (2009) Anthropogenic perturbations of the silicon cycle at the global scale: Key role of the land-ocean transition. Global Biogeochem Cycles 23: GB4031. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hodson MJ, White PJ, Mead A, Broadley MR (2005) Phylogenetic Variation in the Silicon Composition of Plants. Annals of Botany 96: 1027–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houghton RA, Skole DL (1990) Carbon. In: Turner BLI, editor. The Earth As Transformed by Human Action: Global and Regional Changes in the Biosphere over the past 300 Years New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Knoop WT, Walker BH (1985) Interactions of Woody and Herbaceous Vegetation in a Southern African Savanna. Journal of Ecology 73: 235–253. [Google Scholar]

- 19.FAO (2010) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). faostat.fao.org. [PubMed]

- 20. Tilman D, Fargione J, Wolff B, D'Antonio C, Dobson A, et al. (2001) Forecasting Agriculturally Driven Global Environmental Change. Science 292: 281–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amos GL (1952) Silica in Timbers. Melbourne, Australia: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koeppen RC (1978) Some Anatomical Characteristics of Tropical Woods. U.S. Forest Service Department of Agriculture. Madison, WI 15. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fulweiler RW, Nixon SW (2005) Terrestrial vegetation and the seasonal cycleof dissolved silica in a southern New Englandcoastal river. Biogeochemistry 74: 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Litton CM, Raich JW, Ryan MG (2007) Carbon allocation in forest ecosystems. Global Change Biology 13: 2089–2109. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rockstrom J, Steffen W, Noone K, Persson A, Chapin FS, et al. (2009) A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461: 472–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Humborg C, Ittekkot V, Cociasu A, Bodungen Bv (1997) Effect of Danube River dam on Black Sea biogeochemistry and ecosystem structure. Nature 386: 385–388. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Conley D, Schelske CL, Stoermer EF (1993) Modification of the biogeochemical cycle of silica with eutrophication. Marine Ecoogy Progress Series 101: 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Turner RE, Qureshi N, Rabalais NN, Dortch Q, Justic D, et al. (1998) Fluctuating silicate:nitrate ratios and coastal plankton food webs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95: 13048–13051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Danielsson Å, Papush L, Rahm L (2008) Alterations in nutrient limitations – Scenarios of a changing Baltic Sea. Journal of Marine Systems 73: 263–283. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Officer CB, Ryther JH (1980) The possible importance of silicon in marine eutrophication. Marine Ecoogy Progress Series 3: 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Admiraal W, Breugem P, Jacobs DMLHA, Steveninck ED (1990) Fixation of dissolved silicate and sedimentation of biogenic silicate in the lower river Rhine during diatom blooms. Biogeochemistry 9: 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vandevenne F, Struyf E, Clymans W, Meire P (2011) Agricultural silica harvest: have humans created a new loop in the global silica cycle? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 10: 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carey JC, Fulweiler RW (2011) Human activities directly alter watershed dissolved silica fluxes. Biogeochemistry DOI:10.1007/s10533-011-9671-2.

- 34. Sferratore A, Garnier J, Billen G, Conley DJ, Pinault S (2006) Diffuse and point sources of silica in the Seine River watershed. Environmental Science & Technology 40: 6630–6635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Struyf E, Smis A, Van Damme S, Garnier J, Govers G, et al. (2010) Historical land use change has lowered terrestrial silica mobilization. Nat Commun 1: 129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Clymans W, Struyf E, Govers G, Vandevenne F, D.J C (2011) Anthropogenic impact on biogenic Si pools in temperate soils. Biogeoscience Discussion 8: 4391–4419. [Google Scholar]