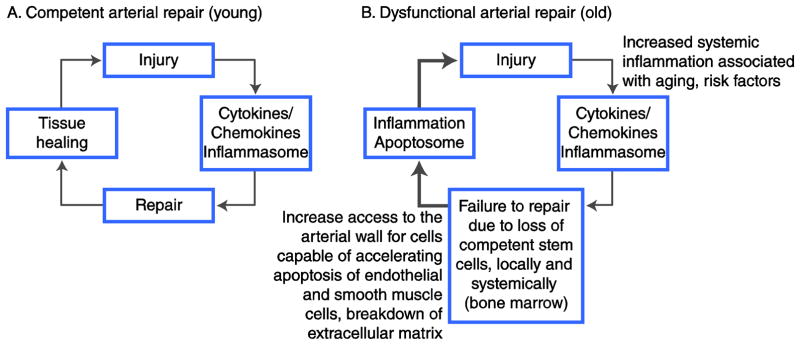

Figure 3.

Impact of effective arterial repair, or lack thereof, on arterial inflammation. A, In young individuals, the repair capacity of the arterial wall is almost always intact, with local and systemic reservoirs of stem/progenitor cells that are competent to repair an injured artery. As a consequence, an arterial injury triggers a limited inflammatory response, which is mediated by chemokines, cytokines, interleukins, and growth factors (such as vascular endothelial growth factor). The cellular inflammation response (cytoplasmic inflammasome) serves as a signal for the recruitment of inflammatory cells, but also stem/progenitor cells capable of repair, to the area of damaged arteries. Consequently, the artery is successfully repaired and the inflammation ceases (ie, a negative feedback loop). B, In older individuals, the repair capacity may become progressively exhausted. Once the bone marrow and other local reservoirs for repair-competent stem/progenitor cells are depleted, injury to the arterial wall triggers an inflammatory reaction that does not result in successful repair and, consequently, in the absence of negative feedback loop, inflammation continues unregulated (systemic elevation of C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation). An unregulated inflammatory reaction at the level of the arterial wall contributes to larger atheroma, and unstable lesions ensue when the cellular inflammation response leads to rapid cell death (cytoplasmic apoptosome). In this situation, a positive feedback loop occurs, and unstable clinical events can occur as a consequence of plaque ulceration/rupture and thrombotic complications.