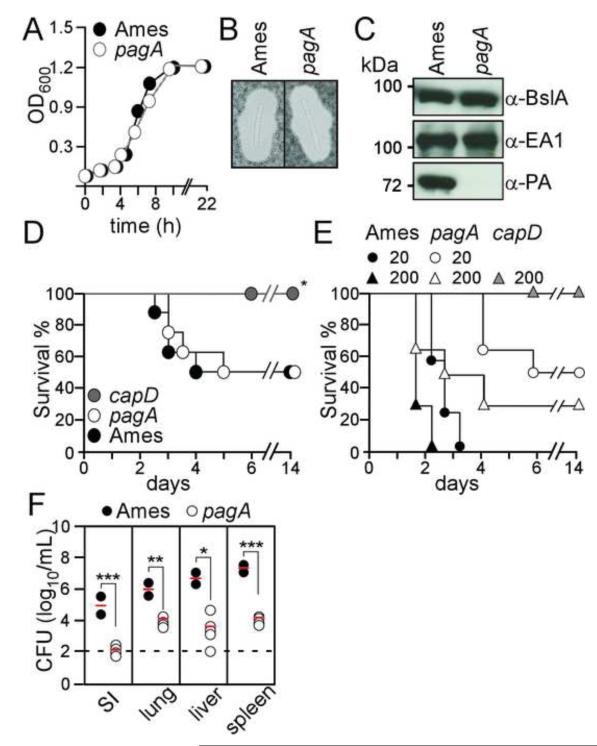

Fig. 3.

Protective antigen (pagA) deficient Bacillus anthracis Ames are attenuated in guinea pigs. (A) Growth of wild-type and pagA mutant B. anthracis Ames in LB broth cultures were monitored as the absorbance at 600 nm. (B) B. anthracis wild-type (Ames) and pagA mutant strains were grown in the presence of carbon dioxide and stained with India ink to reveal the poly-D-γ-glutamic acid (PDGA) capsule. (C) Immunoblotting of B. anthracis culture supernatants with rabbit antibodies specific for BslA, EA1 and protective antigen (PA). (D) Wild-type B. anthracis (Ames), pagA and capD mutant spores (3×102 CFU) were injected into the peritoneal cavity of C57Bl/6 mice and animal morbidity and mortality was monitored. Statistical significance was examined with the Log-rank test (* indicates P <0.01). Data are representative of two independent determinations. (E) B. anthracis wild-type (Ames), pagA and capD mutant spores were injected into the inguinal fold of guinea pigs; animal survival and disease were monitored. The Log-rank test was used to determine significance in animal survival: capD (200 spores) vs. wild-type (Ames) (20 spores); P<0.01. (F) B. anthracis replication at the site of infection (SI) or dissemination into lung, liver and spleen was enumerated by plating homogenized tissues on agar media and incubation for colony formation. Differences in bacterial load between wild-type (Ames) and pagA mutant were examined with the unpaired two-tailed student’s t-test: *P<0.05, **P<0.001, ***P<0.0001. Data are representative of two independent determinations.