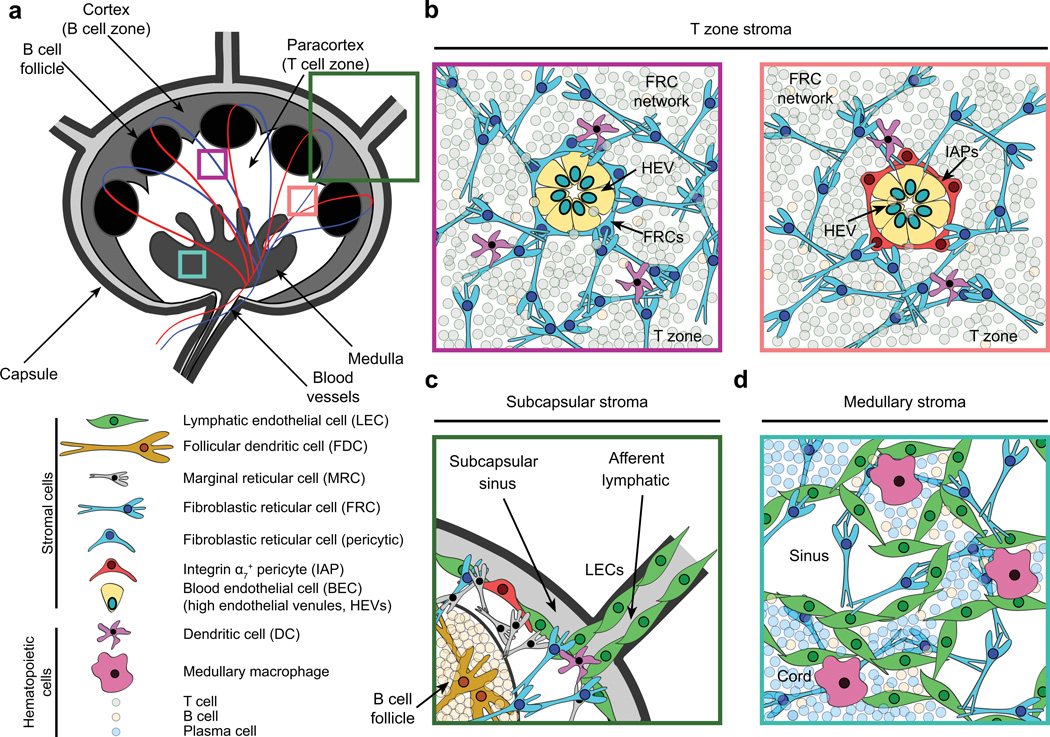

Fig. 1. Lymph node architecture and stromal cell localization.

(A) Cartoon depicting lymph node architecture and compartmentalization. (B) Naive lymphocytes gain access to lymph nodes through high endothelial venules (HEVs). HEVs are comprised of specialized blood endothelial cells (BECs) that regulate lymphocyte entry into lymph nodes via expression of molecules such as peripheral node addressins. These structures are routinely surrounded by a layer of fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs, left). However, a small proportion (<15%) of these gateways are instead ensheathed by integrin α7+ pericytes (IAPs, right). Both types of HEVs appear similar histologically. Furthermore, they connect to the dense FRC network within the paracortex, providing a continuous scaffold on which naive lymphocytes and dendritic cells crawl and interact. FRCs also promote naive T-cell survival through the secretion of IL-7. (C) Interstitial fluid and migratory dendritic cells enter lymph nodes through afferent lymphatics, which are lined by lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs). Between the capsule and the lymph node parenchyma lies the subcapsular sinus (SCS), within which lymph percolates, allowing antigen uptake by macrophages. FRCs, CXCL13-secreting marginal reticular cells, and IAPs are also found proximal to the SCS. B-cell follicles contain a specialized stromal subset (follicular dendritic cells), which interacts with B lymphocytes and continually captures and displays antigens on its surface via complement receptors. (D) The lymph node medulla contains macrophages, B cells, plasma cells, and a dense LEC network that regulates lymphocyte egress through efferent lymphatics.