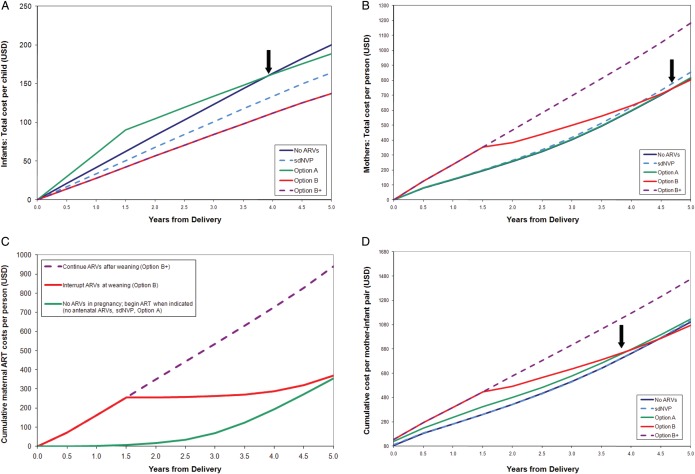

Figure 2.

Projected costs (in US dollars [USD]) over the first 5 years after delivery for modeled prevention of mother-to-child human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission (PMTCT) regimens in Zimbabwe. A–D, Undiscounted costs are shown on the vertical axis, and time from delivery is shown on the horizontal access. A, Total healthcare costs for infants (with 100% pediatric antiretroviral therapy [ART] availability). The costs of daily infant nevirapine (NVP) prophylaxis (Option A) are included in pediatric healthcare costs. Because infant NVP is modeled as a pediatric cost, Option A is more expensive than the others during the first 18 months (while breastfeeding continues). PMTCT regimens that are more effective in preventing infant infections result in slower increases in costs (flatter slopes) as time progresses because pediatric HIV care costs are averted, and the pediatric care costs following Option A become less than those following no antenatal antiretroviral medications (ARVs) by 4 years after delivery (arrow). B, HIV-related healthcare costs for women after delivery (with 100% retention in care). The costs of maternal ART and 3-drug ARV prophylaxis (Options B and B+) are included in maternal HIV-related healthcare costs. Postnatal care costs are similar following the no antenatal ARVs, single-dose NVP (sdNVP), and Option A strategies: women enrolled in HIV-related care following all 3 of these strategies are assumed to begin ART when CD4 count falls to ≤350 cells/µL or stage 3–4 disease develops. Small cost differences result from assumptions regarding NNRTI resistance following sdNVP, but the slopes of these 3lines are similar. In Option B+, all women continue their 3-drug regimens. In Option B, women who did not have advanced disease before pregnancy interrupt their ARVs but remain in care and re-initiate ART once CD4 count falls to ≤350 cells/µL or stage 3–4 disease develops. As a result, maternal costs after weaning are greater with Option B+ than with the other regimens, and costs for Option B (due to delayed ART use) are much lower after weaning (becoming less than the costs after Option A by 5 years after delivery) (arrow). Antenatal costs are not included in (A and B). C, HIV-infected women with CD4 count >350 cells/µL, post-delivery. ART costs for women not eligible for ART during pregnancy (CD4 count >350 cells/µL, no stage 3–4 disease), from the Cost-effectiveness of Preventing AIDS Complications (CEPAC) adult model. Three postnatal scenarios are shown: (1) initiate 3-drug ARVs in pregnancy and continue ARVs after weaning (as in Option B+); (2) initiate 3-drug ARVs in pregnancy and interrupt ARVs after weaning (Option B); and (3) do not initiate ARVs in pregnancy but remain in care and initiate ART when needed (CD4 count ≤350 cells/µL or stage 3–4 disease, as in the no antenatal ARVs, sdNVP, and Option A strategies). Interrupting ART at weaning saves money compared with continuing ART; however, this ART interruption may be associated with negative health impacts for HIV-infected mothers if retention in care is less than 100% (Table 2). D, Total cohort costs over the first 5 years after delivery. These include antenatal care costs (through delivery), maternal HIV-related healthcare costs, and pediatric healthcare costs. Option B becomes cost-saving compared with Option A within 4 years after delivery (arrow). Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; ARV, antiretroviral medication; sdNVP, single-dose nevirapine.