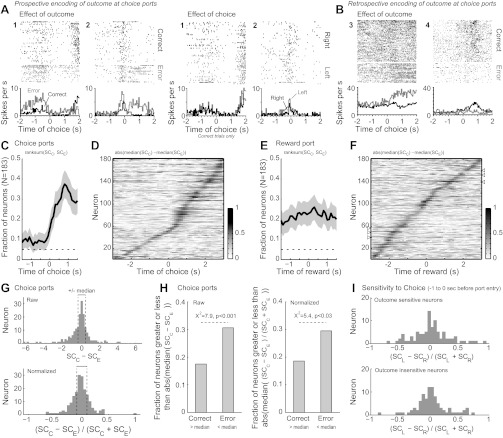

Fig. 5.

Neurons encoded trial outcomes, both prospectively and retrospectively. A: examples of neurons that fired at distinct rates at the choice ports on trials with correct and incorrect responding. Spike activity is shown for 2 simultaneously recorded neurons. In plots on left, trials were scored as correct or incorrect independent of the location of the choice. Neuron 1 fired persistently at a higher rate during the period before incorrect entries into the choice ports compared with correct port entries. Neuron 2 fired at a higher rate immediately prior to the incorrect port entries and also fired irregularly after the outcome was revealed, during the period when the rat traveled to the reward port. To examine whether the error trials reflected a “miscoding” of the forthcoming choice, in plots on right we plotted the spike activity for correct trials only and sorted the trials by the location of the choice (left or right). Both neurons fired at low, equivalent rates during entries into the 2 ports, providing evidence that neurons in the mPFC can prospectively encode trial outcomes prior to the rat's choice. B: examples of neurons that fired differently after correct and incorrect responding. Neuron 3 fired more spikes after incorrect responses were made. Neuron 4 fired more after correct responses were made. Feedback about the trial outcome was given at a latency of 0.04 s. (Note for A and B: Rasters for effects of outcome were sorted by the travel time to the reward port. Rasters for the effects of choice were plotted in the observed trial orders.) C: fraction of neurons that was sensitive to the trial outcome when rats entered the choice ports. D: normalized difference in spike counts around choice port entry for trials with correct and incorrect responses. As in Fig. 4C, none of the neurons fired at distinct rates throughout the period of the choice based on the outcome of the trial, neither before nor after the choice. Many neurons showed differences in spike counts immediately after feedback was given (0.1–0.5 s after port entry). E: fraction of neurons that was sensitive to the trial outcome when rats entered the reward port. About 20% of neurons were sensitive to outcome throughout this period. F: normalized difference in spike counts around choice port entry for trials with correct and incorrect responses. While most neurons fired selectively after correct and incorrect responses for no more than 1 s, some neurons did fire persistently during this period of the task (arrowheads near 60 and 140 on the y-axis). G: distribution of preference scores for correct and error trials based on raw (top) and normalized (bottom) spike counts for the database of 183 neurons. The median values of the absolute preference scores (shown as dashed lines) were used to characterize whether the cells' firing rates were sensitive to the trial outcome before the choice was made. H: the fractions of cells that showed differences in spike counts that were greater than the median value of the absolute difference in spike counts for the correct and error trials are summarized. Results are summarized as fractions based on raw (left) and normalized (right) measures of activity. For both measures of activity, significantly more cells fired more spikes prior to incorrect responses compared with correct responses based on a proportions test. I: the distributions of preference scores for left and right choices on correct trials were similar for the subpopulations of outcome-sensitive (top) and outcome-insensitive (bottom) neurons.