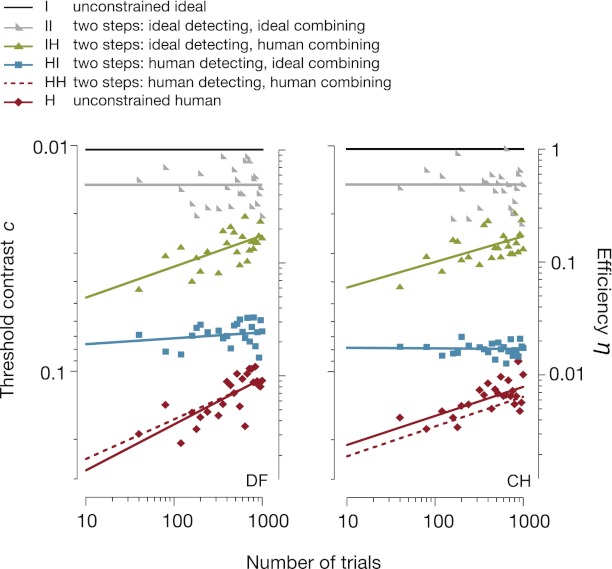

Fig. 2.

Learning. The participant (DF, Left; CH, Right) detects and combines features to identify a letter from an alphabet of eight different IndyEighteen letters. Each unconstrained or composite observer trained at threshold contrast, receiving just enough contrast to achieve criterion performance (75% correct). Each line shows an unconstrained or composite observer’s threshold contrast c (using the contrast scale, Left) and efficiency η (using the efficiency scale, Right). The bottom solid line is the unconstrained human (H), and the top line is the unconstrained ideal (I). The dashed line is the composite human (HH). Separability of the two steps predicts that the unconstrained and composite observers will perform equally, which is approximately true for the human H and HH (bottom two lines, solid and dashed) and is not true of the ideal I II (top two lines). The horizontal scale counts identification trials. For composite HI, the human performs 18 detection trials for each identification trial. In both vertical scales, learning goes up: efficiency increases upward and threshold contrast increases downward. Because efficiency is inversely proportional to threshold contrast squared (Eq. 1), the log-log slope of efficiency is −2× that of threshold contrast.