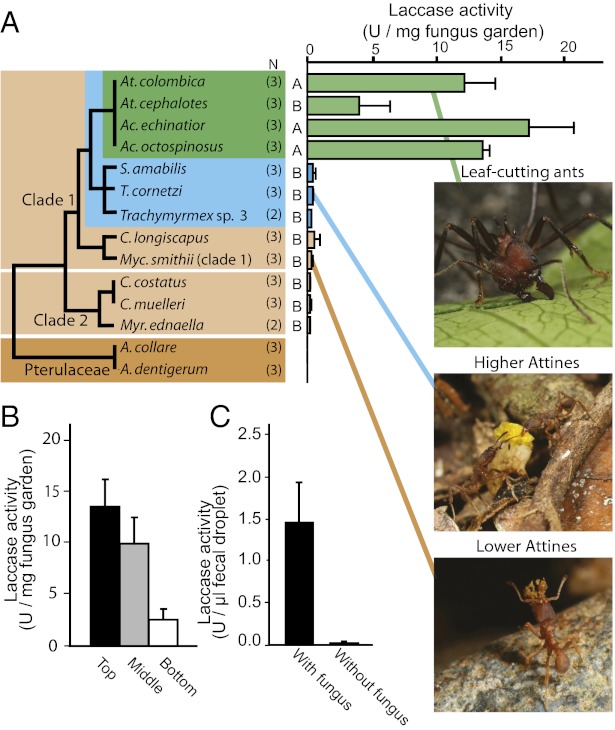

Fig. 2.

Fungus garden laccase activity in units per milligram of fungus garden (units = unit oxidizing 1 nmol syringaldazine per minute) + SE for representative attine ants from Panama. (A) Simplified fungal phylogeny showing laccase activity in newly built sections of laboratory fungus gardens of 14 ant species representing 8 of the 15 attine ant genera. Dark brown: pterulaceous fungi cultivated by debris-foraging Apterostigma (almost no activity); light brown: lower-attine ants (Myrmicocrypta, Mycocepurus, and Cyphomyrmex) cultivating either clade 1 or clade 2 leucocoprinaceous fungi on a substrate of mostly dead plant material (very low activity); blue: higher attine ants (Trachymyrmex and Sericomyrmex) cultivating fungi with gongylidia on a substrate of mostly flowers and soft shed leaves (very low activity); green: leaf-cutting ants (Acromyrmex and Atta) cultivating L. gongylophorus (high activity)(n = number of colonies; A and B indicate significantly different means in post hoc tests following ANOVA, F13,39 = 19.48, P < 0.0001). (B) Laccase activity (units per milligram + SE) in the top, middle, and bottom sections of laboratory fungus gardens of three A. echinatior colonies (see SI Appendix, Fig. S2 for similar data on other leaf-cutting ants) showing that laccase activity decreases from top to bottom (ANOVA: F2,6 = 6.33, P = 0.0332). (C) Fecal droplet laccase activity (units per microliter + SE) of medium-sized A. echinatior workers from laboratory colonies with a fungus garden and from workers kept on sugar water for 20 d without a fungus garden (ANOVA: F1,4 = 8.93, P = 0.0404, five workers measured from each of three A. echinatior colonies).