Abstract

BACKGROUND

Our objective was to determine how patient preferences guide the course of palliative chemotherapy for advanced colorectal cancer.

METHODS

Eligible patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) were enrolled nationwide in a prospective, population-based cohort study. Data were obtained via medical record abstraction and patient surveys. Logistic regression was used to evaluate: patient characteristics associated with seeing medical oncology and receiving chemotherapy; and patient characteristics, beliefs and preferences associated with receiving >1 line of chemotherapy and receiving combination chemotherapy.

RESULTS

Among 702 patients with mCRC, 91% saw a medical oncologist, and among those, 82% received chemotherapy. Patients 65-75 and ≥75 years were less likely to see an oncologist, as were patients who were too sick to complete their own survey. In adjusted analyses patients ≥75 years and with moderate or severe comorbidity were less likely to receive chemotherapy, as were patients who were too sick to complete their own survey. Patients received chemotherapy even if they believed chemotherapy would not extend their life (90%), chemotherapy would not likely help with cancer-related problems (89%), or preferred treatment focusing on comfort even if it meant not living as long (90%). Older patients were less likely to receive combination first-line therapy. Patient preferences and beliefs were not associated with receipt of >1 line of chemotherapy or combination chemotherapy.

CONCLUSIONS

The majority of patients received chemotherapy even if they expressed negative or marginal preferences or beliefs regarding chemotherapy. Patient preferences and beliefs were not associated with intensity or number of chemotherapy regimens.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, decision making, patient preference, cohort studies, quality of healthcare

BACKGROUND

A growing body of evidence has demonstrated the value of patient-centered care. Patients involved in decision-making are more knowledgeable about their care and more satisfied with their care.1, 2 Patient dissatisfaction with treatment-related decision-making may negatively impact the quality of cancer care.3 Patient preferences should be particularly emphasized in the setting of advanced cancer, where the treatment is palliative. For example, while chemotherapy for patients with advanced colorectal cancer can modestly extend survival, it is associated with risk of significant toxicity.4 This balance between possible benefit versus probable risk necessitates a patient-centered approach to treatment decision-making. However, studies suggest improper use of chemotherapy near the end of life may reflect inadequate shared decision-making between patient and physician.5 Physicians may find it easier to offer chemotherapy for the patient with advanced cancer rather than engaging in challenging end-of-life discussions.6 For their part, patients might prefer to take a passive decision-making role when considering therapy for advanced cancer.7, 8 What remains unclear is how patient preferences guide the course of palliative chemotherapy for advanced cancer.

To evaluate the quality of patient-centered care for patients with advanced cancer, an important question must be answered: do patient preferences play a role in treatment-related decision-making for palliative chemotherapy? We conducted a multiregional cohort study of patients with advanced colorectal cancer to assess factors associated with seeing a medical oncologist and receipt of chemotherapy, specifically addressing the effect of the patient’s role in decision-making, quality of communication with their physician, overall quality of care, preferences for treatment, and their beliefs and concerns regarding treatment. We hypothesized that patient preferences would play a role in treatment-related decision-making.

METHODS

Patients

Study participants were enrolled by the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) Consortium. CanCORS is a prospective, observational, population- and healthcare systems-based cohort study to determine how characteristics and beliefs of cancer patients, providers, and health care organizations influence treatments and outcomes.9 Patients 21 years or older with colorectal cancer were enrolled from one of the following: five geographic regions, five integrated health care systems in the NCI-funded Cancer Research Network, or fifteen Veterans Administration (VA) Hospitals from September, 2003 to January, 2006 within three months of diagnosis. Patients were followed for 15 months past enrollment. Only patients with stage IV colorectal cancer (n=702) were included in this analysis.

Data collection

Primary data were collected from medical records, patient surveys, and surrogate surveys.9-11 Trained abstractors at each of the data-collection sites abstracted medical records data, including cancer diagnosis, initial tumor location, and stage. Medical record data were also used to verify medical oncology visits, determine the first line of chemotherapy delivered (defined as the first chemotherapy regimen used to treat the patient’s metastatic colorectal cancer), and determine whether the first line of therapy was single agent or combination therapy (more than one chemotherapeutic agent). Comorbidity was abstracted from the medical record and scored using the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation 27 (ACE-27), a 27-item index developed to provide prognostic information for cancer patients.12

Patient surveys were completed in English, Chinese, and Spanish using computer-assisted telephone interviews. A surrogate (relative or household member) familiar with the patient’s cancer care was interviewed for patients who had died or were too ill to be interviewed. The surveys (available at www.cancors.org/public) used previously validated items and scales whenever possible and assessed patients’ sociodemographic characteristics (age, race/ethnicity, annual income), insurance coverage, comorbid conditions, and beliefs about cancer care; survey development has been previously described.11 Surveys also assessed quality of communication with their physician (5 items),11 overall quality of care (2 items), preferences for treatment (2 items), and beliefs and concerns regarding treatment (9 items).13 For patients who were too ill (n=60) or had died (n=140), a survey was administered to a surrogate when available. Most patients completed the survey after treatment was started. Human subject committees approved the study protocol at each participating site.

Statistical analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics summarizing sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidity, treatment, and survey-based patient preferences and beliefs. We used logistic regression to assess factors associated with seeing a medical oncologist and receipt of chemotherapy. Four analytic models were developed to assess factors associated with: (1) seeing a medical oncologist anytime prior to survey completion; (2) receipt of chemotherapy; (3) receipt of combination vs. single-agent first-line therapy; and (4) receipt of only one vs. more than one lines of therapy. In models 3 and 4 we considered the variables addressing role in chemotherapy decision-making, quality of communication with their physician, overall quality of care, preferences for treatment, and beliefs and concerns regarding treatment. These variables were not included in model 1 since not all of those patients completed a survey. These variables were not included in model 2 since they are available only for patients seeing an oncologist and completing full surveys (n=409). Among patients completing a full survey, only 23 patients did not receive chemotherapy. An effective sample of 23 was too small to produce reliable results in logistic regression.

A consistent model building approach was used for all outcomes. Four variables were included unconditionally in all models: age, comorbidity, gender, and race. Survey respondent (patient vs. surrogate) was included as a variable in models 1 and 2. Step-wise model refinement was applied with p=0.20 criterion for entering variables into the models and p=0.10 criterion for removing them from the models. If necessary to prevent overfitting, the least significant variables were removed to attain model degrees of freedom to effective sample size ratio of ≥714. Multiple imputation was used to address item nonresponse for survey-based variables and was performed centrally by the CanCORS Statistical Coordinating Center.15 Results from multivariable models incorporate formal imputation adjustments.16

Data analysis was conducted at the Durham VA Medical Center, the coordinating site for VA hospitals participating in CanCORS. This analysis used CanCORS core data (version 1.9), medical record data (version 1.9), and patient survey data (version 1.8). Statistical analyses were performed using SAS for Windows Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Cohort characteristics

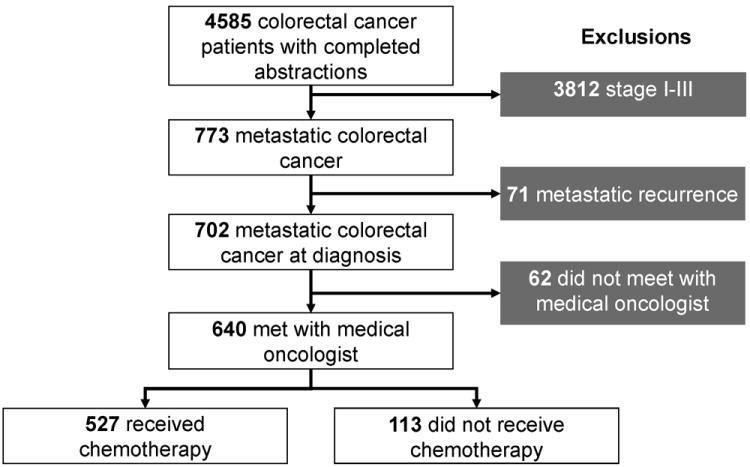

Seven hundred two patients were included in this analysis (Figure 1). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Derivation of study cohort. Of the 640 who met with a medical oncologist, 409 completed a full patient survey. Of those who completed a full survey, only 23 patients did not receive chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n=702).

| Characteristic | n | %* |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||

| <55 | 170 | 24 |

| 55-64 | 168 | 24 |

| 65-74 | 178 | 25 |

| ≥75 | 186 | 27 |

| ACE-27 Comorbidity Index (score) | ||

| None (0) | 221 | 32 |

| Mild (1) | 265 | 38 |

| Moderate (2) | 126 | 18 |

| Severe (3) | 90 | 13 |

| Race | ||

| Unknown | 1 | <1 |

| Non-white | 274 | 39 |

| White | 427 | 61 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 268 | 38 |

| Male | 434 | 62 |

| Insurance | ||

| Missing | 38 | 5 |

| Public | 103 | 15 |

| Medicare + Supplemental | 209 | 30 |

| Veterans Administration | 117 | 17 |

| Private | 235 | 34 |

| Geographic region | ||

| West/Midwest | 421 | 60 |

| South | 146 | 21 |

| Atlantic | 135 | 19 |

| Health system | ||

| Fee-for-Service | 420 | 60 |

| Integrated health system | 282 | 40 |

| Survey respondent | ||

| Survey completed by patient | 441 | 63 |

| Survey completed by patient surrogate | 200 | 29 |

| Survey not completed | 61 | 9 |

| Primary tumor site | ||

| Missing | 7 | 1 |

| Colon | 528 | 75 |

| Rectum | 142 | 20 |

| Colorectal | 25 | 4 |

Percents might not sum to 100 due to rounding.

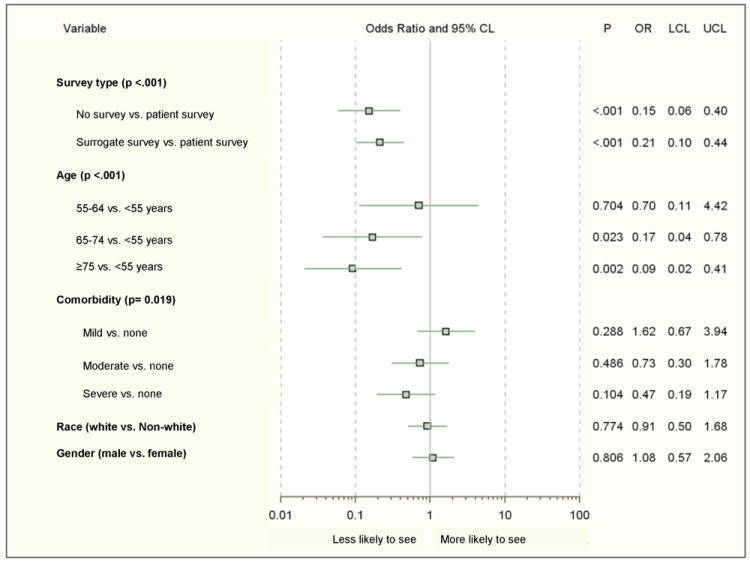

Medical oncology visits

Ninety-one percent of 702 patients had at least one visit with a medical oncologist (n=640, Figure 1). In multivariable analysis (Figure 2), age was associated with seeing an oncologist: patients 65-74 years old and ≥75 years old were less likely than those <55 years old to see an oncologist. Survey type (self-completion vs. completion by a surrogate) was significantly associated with seeing a medical oncologist, reflecting the greater severity of illness and functional decline among patients who were unable to fully participate in the survey. Patients who had their surveys completed by a surrogate or patients without any survey data were less likely to see a medical oncologist than patients who completed their own surveys. Variables addressing role in chemotherapy decision-making, quality of communication with their physician, overall quality of care, preferences for treatment, and beliefs and concerns regarding treatment were not included in this model since they are available only for patients seeing an oncologist and completing full surveys (n=409).

Figure 2.

Factors associated with seeing a medical oncologist (n=702).

CL, confidence limit; OR, adjusted odds ratio; LCL, lower confidence limit; UCL, upper confidence limit

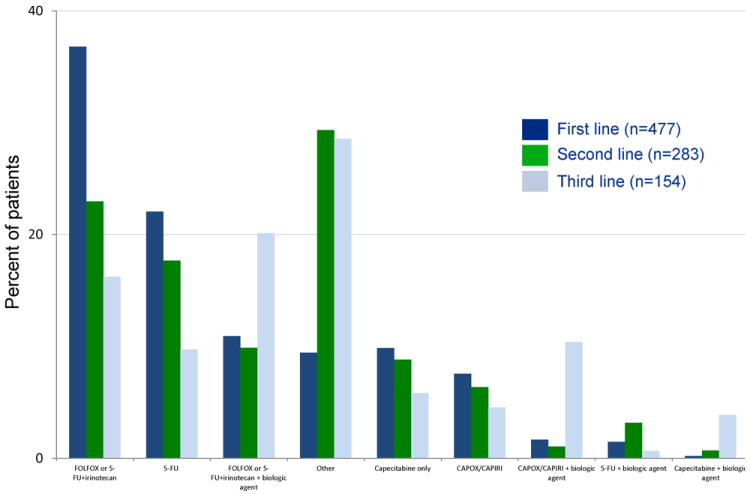

Chemotherapy regimens

Of those who consulted an oncologist (n=640), 527 (82%) received chemotherapy. Figure 3 illustrates the most common first-, second-, and third-line chemotherapy regimens. For their first-line chemotherapy regimen, 32% of patients received only single-agent therapy (e.g., fluorouracil or capecitabine). Among 477 patients with available chemotherapy regimen data, 63% received more than one line of chemotherapy. The regimens used for first-line therapy were generally in concordance with those listed in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s colorectal cancer guidelines between 2003-2006, the period inclusive of patient enrollment.

Figure 3.

Chemotherapy regimens used in the first, second, and third lines.

Receipt of chemotherapy

Unadjusted analyses are presented (Table 2). Among those seeing an oncologist, patients who reported a preference for extending their life were more likely to receive chemotherapy than those focusing on comfort (99% vs. 90%, p<0.001). Patients who believed chemotherapy would extend their life were more likely to receive chemotherapy than those who thought it unlikely that chemotherapy would extend their life (99% vs. 90%, p=0.008). Patients who believed that chemotherapy might help with cancer-related problems were more likely to receive chemotherapy than those who thought chemotherapy would be unlikely to help (100% vs. 89%, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Role of patient preferences and beliefs in receipt of chemotherapy (n=409*).

| Total | No chemotherapy | Received chemotherapy | p-valueˆ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | % | n | % | ||

| If you had to make a choice now, would you prefer treatment that extends life as much as possible, even if it means having more pain and discomfort, or would you want treatment that focuses on relieving pain and discomfort as much as possible, even if it means not living as long? | <0.001 | |||||

| Relieve pain or discomfort as much as possible | 164 | 17 | 10 | 147 | 90 | |

| Extend life as much as possible | 204 | 2 | 1 | 202 | 99 | |

| Declined to answer/ Don’t know | 39 | 1 | 3 | 38 | 97 | |

| Missing response | 2 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| If you had to make a choice now, would you prefer treatment that extends life as much as possible, even if it means using up all of your financial resources, or would you want treatment that costs you less, even if means not living as long? | 0.103 | |||||

| Prefer treatment that costs less | 110 | 8 | 7 | 102 | 93 | |

| Prefer treatment to extend life at the risk of using all financial resources | 245 | 8 | 3 | 237 | 97 | |

| Declined to answer/ Don’t know | 52 | 4 | 8 | 48 | 92 | |

| Missing response | 2 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| After talking with your doctors about chemotherapy, how likely did you think it was that chemotherapy would help you live longer | 0.008 | |||||

| Not likely/ A little likely | 29 | 3 | 10 | 26 | 90 | |

| Somewhat likely/Very likely | 337 | 3 | 1 | 334 | 99 | |

| Not applicable/Don’t know | 20 | 1 | 5 | 19 | 95 | |

| Missing response | 23 | 15 | 65 | 8 | 35 | |

| After talking with your doctors about chemotherapy, how likely did you think it was that chemotherapy would help you with problems you were having because of your [cancer]? | <0.001 | |||||

| Not likely/A little likely | 38 | 4 | 11 | 34 | 89 | |

| Somewhat likely/Very likely | 261 | 0 | 0 | 261 | 100 | |

| Not applicable/Don’t know | 87 | 3 | 3 | 84 | 97 | |

| Missing response | 23 | 15 | 65 | 8 | 35 | |

Limited to survey responses from full patient survey or full surrogate survey for living patients, since items of interest were only asked in these survey versions.

Two-sided Fisher’s exact test excluding missing responses, “not applicable,” or “Don’t know.”

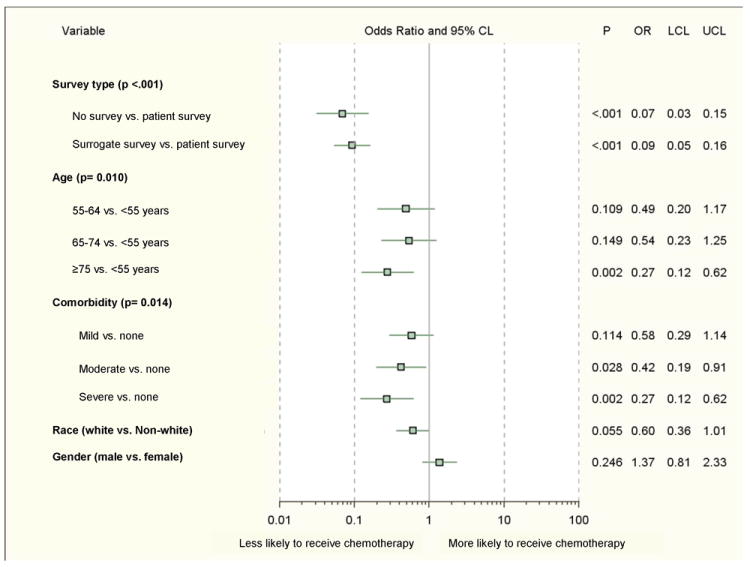

In multivariable analysis (Figure 4) age, comorbidity, and survey respondent were significantly associated with receipt of chemotherapy. The oldest patients (age ≥75 years) were least likely to receive chemotherapy when compared to those <55 years old. Patients with moderate or severe comorbidity were less likely to receive chemotherapy than those with no comorbidity. Patients who had their surveys completed by a surrogate were less likely than patients who completed their own surveys to receive chemotherapy. Patients without any survey data had a similarly lower likelihood of receiving chemotherapy. Variables addressing role in chemotherapy decision-making, quality of communication with their physician, overall quality of care, preferences for treatment, and beliefs and concerns regarding treatment were not included in this model since they are available only for patients seeing an oncologist and completing full surveys (n=409). Among this group only 23 patients did not receive chemotherapy; the effective sample of n=23 would have been too small to produce reliable results in logistic regression models.

Figure 4.

Factors associated with receipt of chemotherapy (n=635; 4 insurance and 1 race values with insufficient data).

CL, confidence limit; OR, adjusted odds ratio; LCL, lower confidence limit; UCL, upper confidence limit

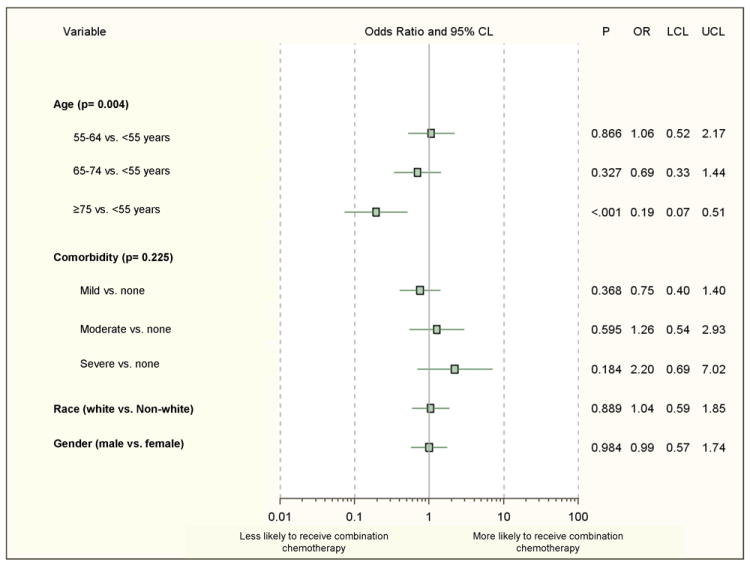

Intensity of first-line chemotherapy

Multivariable analysis examined the association between characteristics, preferences, beliefs and intensity of first-line chemotherapy, as defined by receipt of combination therapy (more than one drug) versus single-agent therapy (Figure 5). The oldest patients were less likely to receive combination therapy as a part of their first-line regimen. Role in decision-making, quality of communication with their physician, overall quality of care, preferences for treatment, beliefs, and concerns regarding treatment were assessed but were not significantly associated with receipt of combination first-line therapy.

Figure 5.

Factors associated with receipt of combination chemotherapy vs. single-agent first-line therapy (n=271; 116 with insufficient data regarding chemotherapy regimens).

CL, confidence limit; OR, adjusted odds ratio; LCL, lower confidence limit; UCL, upper confidence limit

Number of chemotherapy regimens

Multivariable analysis examined the association between characteristics, preferences, beliefs and number of chemotherapy regimens received. Patient characteristics, role in decision-making, quality of communication with their physician, overall quality of care, preferences for treatment, beliefs, and concerns regarding treatment were assessed, but none were significantly associated with receipt of combination first-line therapy (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Given the substantial toxicity and personal costs associated with modest survival gains from metastatic colorectal cancer treatment, we hypothesized patient preferences would play an important role in receipt of palliative chemotherapy. We found patients with beliefs and preferences favoring chemotherapy were statistically more likely to receive treatment. Nonetheless, the vast majority of patients who expressed a preference for comfort-oriented care believed that chemotherapy would be unlikely to extend their life, or did not believe that chemotherapy would help with cancer-related problems still received chemotherapy. Patient preferences, beliefs, concerns about treatment, actual and preferred role in decision-making, and the quality of communication with their physician were not associated with intensity or number of chemotherapy regimens delivered.

Patient preference in palliative chemotherapy decision-making

Why did the majority of patients receive chemotherapy despite reporting beliefs and preferences that would seem incongruent with this treatment choice? Patients who offered negative or marginal views about chemotherapy in our survey might have still elected to receive treatment in the hopes that they fall in the group of patients who experience a meaningful benefit with minimal harm. This sense of optimism might have played a role in our findings since patients who were a “little likely” to expect benefit might have considered the risks of treatment reasonable. Patients with advanced cancer are often more willing than their providers to accept greater risk of harm for smaller benefit.17 In addition, patients might disregard their own negative views of treatment if they are in conflict with their doctor’s view.3, 18, 19

In the metastatic setting where the benefit of treatment is limited, patients may be more likely to defer treatment decision-making to their physician.7 Hence, clinical factors rather than patient preference appear to have a disproportionate role in the treatment decision-making process. Our study indeed suggests that clinical factors, in particular age and comorbidity, influence the receipt of chemotherapy. These findings are consistent with a substantial body of literature showing that older, sicker patients are less likely to receive chemotherapy,17, 20-23 including the analysis by Kahn et al which focused on stage III colorectal cancer patients enrolled in the same study described here.10 Furthermore, completion of the survey by a surrogate rather than the patient likely serves as a proxy for poor performance status.10 We found that completion of a surrogate survey was negatively associated with seeing a medical oncologist, receiving any chemotherapy, and receiving more than one line of chemotherapy. Older patients diagnosed with metastatic colorectal cancer had lower odds of being referred to a medical oncologist. While older patients are at higher risk of being diagnosed with colorectal cancer, our cohort includes patients who have already been diagnosed. Furthermore, our model adjusted for comorbidity, race, and gender. Hence, age remains an independent predictor of referral to medical oncology.

Appropriateness of palliative chemotherapy use

Multiple studies suggest underuse of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colorectal cancer.10, 21, 23-27 Though the same degree of evidence is not available for the palliative setting in the US, though several studies have described low rates of palliative chemotherapy use for advanced colorectal cancer outside the U.S.28-32 However, appropriate use of palliative chemotherapy for advanced cancer is difficult to discern without detailed clinical information. Since guidelines do not recommend treatment of patients with poor performance status, some patients are not candidates for chemotherapy from the time of diagnosis. Our analysis does not suggest an underuse of chemotherapy for advanced colorectal cancer in the U.S. We found that among patients who reported a preference for chemotherapy or favored quantity over quality of life, virtually all received chemotherapy. Additionally, the first-line chemotherapy regimens prescribed were largely those included in clinical guidelines available at the time of data collection. Taken together, these data suggest concerns regarding potential underuse of chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer can largely be put to rest.

Our findings are subject to limitations. We were unable to model the association between preferences, beliefs, and receipt of chemotherapy due to small effective sample sizes. However, unadjusted results are presented and are informative. Additionally, we assessed associations between those variables, intensity of chemotherapy, and number of lines of chemotherapy. We did not collect data detailing the conversation between patient and provider, so we cannot determine how that conversation might have colored patient preferences or beliefs about chemotherapy. Most patients completed the survey after their treatment decisions had been made. Their preferences or beliefs might have been different if measured prior to treatment decision-making. However, over the course of cancer care, patient preferences tend to shift in favor of treatment,33 and the majority of patients who expressed negative opinions towards chemotherapy still received treatment. Furthermore, we were unable to assess the impact of online, print, nursing, or navigation resources in patient decision-making. We did not focus on the use of chemotherapy at the very end of life and cannot comment on overuse in that setting, as has been extensively reported in the literature.5 Our data were collected between 2003-2006, and the focus on shared decision-making has evolved over time. Finally, some survey items pertaining to preference and beliefs were created specifically for CanCORS. Their validity has not been tested, but the survey tool was thoroughly piloted.11

This study has several strengths. Our analyses are supported by both medical record and patient self-reported data. Patients were enrolled from multiple geographic regions and health care settings, and few exclusion criteria were applied. Patients enrolled in CanCORS have been shown to be demographically representative of the geographic regions in which they were enrolled.34

In summary, treatment decisions in the palliative setting were not always congruent with stated preferences and beliefs regarding chemotherapy. The vast majority of patients who expressed negative or marginal preferences or beliefs regarding chemotherapy still received chemotherapy. Patient preferences and beliefs were not associated with intensity or number of chemotherapy regimens delivered. Additionally, underuse of palliative chemotherapy was not evident. These findings shed new light on the patient experience and decision-making in the use of palliative chemotherapy, and can shift the focus of health services research in advanced cancer from investigating underuse of treatment to the inclusion of patient preferences in decision-making. Research should focus on tailoring delivery of care based on patient preferences and beliefs.

Acknowledgments

Research support: Dr. Zafar is supported by the American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant and the Duke Cancer Institute Cancer Control Pilot Award. Ms. Zullig is supported by the National Cancer Institute (5R25CA116339). This work and the CanCORS Consortium are supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute to the Statistical Coordinating Center (U01 CA093344) and the National Cancer Institute-supported Primary Data Collection and Research Centers (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Cancer Research Network (U01 CA093332); Harvard Medical School/Northern California Cancer Center (U01 CA093324); RAND/UCLA (U01 CA093348); University of Alabama at Birmingham (U01 CA093329); University of Iowa (U01 CA093339); and the University of North Carolina (U01 CA093326); the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality (03-438MO-03); and by a Department of Veterans Affairs grant to the Durham VA Medical Center (HSRD CRS 02-164). The study sponsors played no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing, or decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Authors report no relevant financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Whelan T, Levine M, Willan A, et al. Effect of a Decision Aid on Knowledge and Treatment Decision Making for Breast Cancer Surgery. JAMA. 2004;292:435–441. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whelan T, Sawka C, Levine M, et al. Helping Patients Make Informed Choices: A Randomized Trial of a Decision Aid for Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Lymph Node-Negative Breast Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:581–587. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.8.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahn KL, Schneider EC, Malin JL, Adams JL, Epstein AM. Patient centered experiences in breast cancer: predicting long-term adherence to tamoxifen use. Med Care. 2007;45:431–439. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000257193.10760.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyerhardt JA, Li L, Sanoff HK, Carpenter W, Schrag D. Effectiveness of Bevacizumab With First-Line Combination Chemotherapy for Medicare Patients With Stage IV Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:608–615. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.9650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of Cancer Care Near the End of Life: Is It a Quality-of-Care Issue? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3860–3866. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Haes H, Koedoot N. Patient centered decision making in palliative cancer treatment: a world of paradoxes. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keating NL, Beth Landrum M, Arora NK, et al. Cancer Patients’ Roles in Treatment Decisions: Do Characteristics of the Decision Influence Roles? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4364–4370. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elkin EB, Kim SHM, Casper ES, Kissane DW, Schrag D. Desire for Information and Involvement in Treatment Decisions: Elderly Cancer Patients’ Preferences and Their Physicians’ Perceptions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5275–5280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Wallace RB, et al. Understanding Cancer Treatment and Outcomes: The Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2992–2996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn KL, Adams JL, Weeks JC, et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy Use and Adverse Events Among Older Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer. JAMA. 2010;303:1037–1045. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malin J, Ko C, Ayanian J, et al. Understanding cancer patients’ experience and outcomes: development and pilot study of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance patient survey. Supp Care Cancer. 2006;14:837–848. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piccirillo JF, Tierney RM, Costas I, Grove L, Spitznagel EL., Jr Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA. 2004;291:2441–2447. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malin JL, Ko C, Ayanian JZ, et al. Understanding cancer patients’ experience and outcomes: development and pilot study of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance patient survey. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:837–848. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vittinghoff E, McCulloch CE. Relaxing the Rule of Ten Events per Variable in Logistic and Cox Regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:710–718. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He Y, Zaslavsky AM, Harrington DP, Catalano PJ, Landrum MB. Imputation in a multiformat and multiwave survey of cancer care. Paper presented at: Proc Health Policy Stat, American Statistical Association. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zafar SY, Alexander SC, Weinfurt KP, Schulman KA, Abernethy AP. Decision making and quality of life in the treatment of cancer: a review. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:117–127. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molenaar S, Oort F, Sprangers M, et al. Predictors of patients’ choices for breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy: a prospective study. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2123–2130. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark HD, O’Connor AM, Graham ID, Wells GA. What factors are associated with a woman’s decision to take hormone replacement therapy? Evaluated in the context of a decision aid. Health Expectations. 2003;6:110–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2003.00216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodgson DC, Fuchs CS, Ayanian JZ. Impact of Patient and Provider Characteristics on the Treatment and Outcomes of Colorectal Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:501–515. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.7.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potosky AL, Harlan LC, Kaplan RS, Johnson KA, Lynch CF. Age, sex, and racial differences in the use of standard adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1192–1202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Klabunde CN, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer: do physicians agree about the importance of patient age and comorbidity? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2532–2537. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrag D, Cramer LD, Bach PB, Begg CB. Age and Adjuvant Chemotherapy Use After Surgery for Stage III Colon Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:850–857. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cronin DP, Harlan LC, Potosky AL, Clegg LX, Stevens JL, Mooney MM. Patterns of care for adjuvant therapy in a random population-based sample of patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2308–2318. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jessup JM, Stewart A, Greene FL, Minsky BD. Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage III Colon Cancer. JAMA. 2005;294:2703–2711. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.21.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross C, McAvay G, Guo Z, Tinetti M. The impact of chronic illnesses on the use and effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. Cancer. 2007;109:2410–2419. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Fuchs CS, et al. Use of Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy for Colorectal Cancer in a Population-Based Cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1293–1300. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neo EL, Beeke C, Price T, et al. South Australian clinical registry for metastatic colorectal cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2011;81:352–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price T, Pittman K, Patterson W, et al. Management and survival trends in advanced colorectal cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2008;20:626–630. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Pool AE, Damhuis RA, Ijzermans JN, et al. Trends in incidence, treatment and survival of patients with stage IV colorectal cancer; a population-based series. Colorectal Dis. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ksienski D, Woods R, Speers C, Kennecke H. Patterns of Referral and Resection Among Patients with Liver-Only Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (MCRC) Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3085–3093. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Renouf D, Kennecke H, Gill S. Trends in chemotherapy utilization for colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2008;7:386–389. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2008.n.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stiggelbout AM, de Haes JCJM. Patient Preference for Cancer Therapy: An Overview of Measurement Approaches. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:220–230. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Catalano PJ, Ayanian JZ, Weeks JC, et al. Representativeness of Participants in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium Relative to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Med Care. 2012 doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318222a711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]