Summary

Background

Significant atherosclerotic stenosis of internal carotid artery (ICA) origin is common (5–10% at ≥60 years). Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) enables high-resolution (120 μm) plaque imaging, and IVUS-elucidated features of the coronary plaque were recently shown to be associated with its symptomatic rupture/thrombosis risk. Safety of the significant carotid plaque IVUS imaging in a large unselected population is unknown.

Material/Methods

We prospectively evaluated the safety of embolic protection device (EPD)-assisted vs. unprotected ICA-IVUS in a series of consecutive subjects with ≥50% ICA stenosis referred for carotid artery stenting (CAS), including 104 asymptomatic (aS) and 187 symptomatic (S) subjects (age 47–83 y, 187 men). EPD use was optional for IVUS, but mandatory for CAS.

Results

Evaluation was performed of 107 ICAs (36.8%) without EPD and 184 with EPD. Lesions imaged under EPD were overall more severe (peak-systolic velocity 2.97±0.08 vs. 2.20±0.08m/s, end-diastolic velocity 1.0±0.04 vs. 0.7±0.03 m/s, stenosis severity of 85.7±0.5% vs. 77.7±0.6% by catheter angiography; mean ±SEM; p<0.01 for all comparisons) and more frequently S (50.0% vs. 34.6%, p=0.01). No ICA perforation or dissection, and no major stroke or death occurred. There was no IVUS-triggered cerebral embolization. In the procedures of (i) unprotected IVUS and no CAS, (ii) unprotected IVUS followed by CAS (filters – 39, flow reversal/blockade – 3), (iii) EPD-protected (filters – 135, flow reversal/blockade – 48) IVUS+CAS, TIA occurred in 1.5% vs. 4.8% vs. 2.7%, respectively, and minor stroke in 0% vs. 2.4% vs. 2.1%, respectively. EPD intolerance (on-filter ICA spasm or flow reversal/blockade intolerance) occurred in 9/225 (4.0%). IVUS increased the procedure duration by 7.27±0.19 min.

Conclusions

Carotid IVUS is safe and, for the less severe lesions in particular, it may not require mandatory EPD use. High-risk lesions can be safely evaluated with IVUS under flow reversal/blockade.

Keywords: intravascular ultrasound, carotid artery stenosis, embolic protection device

Background

Moderate or severe stenosis of the extracranial internal carotid artery (ICA) is present in 5–10% of persons over 60 years of age [1], and 20–30% of acute strokes are associated with significant extracranial carotid artery disease (stenosis ≥50% or occlusion) [2]. Eight in every 10 patients with large-artery ischaemic stroke have no preceding warning signs (transient ischaemic attack, TIA) that would prompt them to seek medical help prior to the devastating event [3], and 30% of stroke survivors are permanently disabled [1]. It is clear that, for these patients, any interventional treatment to remove or mechanically stabilize the carotid plaque (carotid endarterectomy, CEA, or carotid artery stenting, CAS) is offered already “too late”, emphasizing the role of primary stroke prevention. Although the current AHA/ASA Guidelines for the Primary Prevention of Stroke [1] list carotid artery stenosis among the well-documented and modifiable risk factors of ischaemic stroke, the role of CAS or CEA in asymptomatic patients is intensely debated [4–7], and no screening for carotid artery stenosis is currently recommended [8]. This is because at the population level the annual risk of stroke with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis is relatively low (asymptomatic stenoses convert to symptomatic stenoses at 0.5–3% per year) [1,4–7,9]. Thus many patients with asymptomatic stenosis will live for decades without a progression to symptoms, whereas only a small minority will have a devastating brain infarction. Although randomized trials indicated that the patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis do benefit from CEA (relative reduction of ipsilateral stroke risk by 50%, with the benefit maintained for at least 10 years and significant irrespective of the lipid-lowering and anti-platelet therapy [10]), the number of interventions needed to prevent 1 stroke in 10 years is very high (≈20–100) [10,11], and this statistic is likely to apply to CAS as well [1,12]. Moreover, contrary to the widely-held assumption that in asymptomatic patients the stroke risk increases with the degree of ICA stenosis [5], data from the medically-treated arm in the Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Study (ACAS) and Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST) clearly show that in subjects with ≥50% carotid artery stenosis there is no association between the actual degree of stenosis and risk of stroke [10,11]. Routine ICA stenosis imaging tools, such as duplex ultrasound (DUS), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) angiography, or computed tomography (CT) angiography, perform poorly in stratifying the patients according to stroke risk. Although recent data suggested that the absence of intra-plaque hemorrhage by MRI carotid plaque imaging has a high negative predictive value for stroke risk [12], the specificity of the finding of intra-plaque hemorrhage is only moderate [12,13]. Thus, at present, the treatment of asymptomatic carotid stenosis remains the treatment of statistical risk rather than individual risk-assessment based treatment of those patients who are likely to have a stroke despite optimal pharmacological management [1,10,14,15].

Intravascular ultrasound imaging (IVUS) is the standard of reference for imaging coronary and peripheral vessel wall morphology [16,17] and it enables a high-resolution (≤120 μm for a 20 MHz scanner [16]) characterization of the atherosclerotic plaque. For over a decade, IVUS has been used in the coronary arteries to precisely determine the degree of stenosis and optimize the result of stenting. In addition, there is recent evidence that IVUS-determined tissue characteristics (radiofrequency IVUS analysis) of the coronary artery plaque may provide an important prognostic information [18]. Prior to embarking on large-scale longitudinal studies with IVUS-elucidation of carotid artery disease, it is mandatory to establish the safety of this technology in the carotid area.

The aim our study was to prospectively assess the safety of IVUS (including IVUS under mechanical embolic protection and unprotected IVUS) in evaluating carotid artery stenosis in a high-volume CAS center.

Material and Methods

Patient population, non-invasive imaging, and neurological consultation

We prospectively evaluated 300 consecutive subjects with symptomatic and asymptomatic ICA stenosis (at least 50% on duplex ultrasound assessment), referred for carotid angiography in the context of carotid revascularization (all-comer population). Non-invasive carotid artery imaging was performed by means of on-site DUS and CT angiography. DUS was performed with a linear 7–10 MHz probe [19]; and both the velocity and NASCET criteria were used for stenosis severity determination [20,21]. Carotid artery CT angiography was performed as previously described [21]. CT area stenosis was calculated as [1 – (minimal lumen area/reference lumen area in the distal non-tapered portion)] × 100%. All patients underwent an independent neurological consultation prior to the invasive imaging [19]. In addition, if the IVUS findings significantly changed the measurement of ICA stenosis severity in reference to duplex ultrasound and CT angiography (‘border-line’ lesions), the neurological consultation on ICA revascularization vs. revascularization deferral was repeated in the cath-lab.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) potential cause for ipsilateral symptoms other than significant carotid artery atherosclerosis (eg, atrial fibrillation, severe intracranial atherosclerosis [22], thrombophilia), (2) restenotic lesion (post-CEA or -CAS), (3) inability to perform IVUS evaluation (eg, lesion severity indicating a need for predilatation prior to potential IVUS imaging), and (4) lack of consent. Index ICA was defined as the ICA (RICA or LICA) subjected to IVUS evaluation. In case of bilateral ICA stenosis in a symptomatic patient, the symptomatic vessel was the index ICA; whereas in asymptomatic patients with bilateral lesions, the more severely stenosed ICA was the target for IVUS imaging.

Following invasive angiography, 7 out of 300 patients (2.3%) could not be included in the IVUS protocol because of the unilateral ‘string-sign’ stenosis precluding insertion of the IVUS catheter through the lesion, and a further 2 patients (0.6%) were excluded (after uncomplicated IVUS acquisibecause of suboptimal IVUS image quality that precluded any quantitative or qualitative image analysis (n=1) or failure to recover the stored IVUS data (n=1). The baseline characteristics of the 291 study patients and index ICA characteristics are shown in Table 1. All patients were on aspirin, thienopyridine and a statin.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study group and index ICA lesions.

| Asymptomatic patients n=104 (35.7%) |

Symptomatic* patients n=187 (64.3%) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean±SEM [range] |

65.7±0.8 [47–84] |

65.9±0.6 [47–83] |

0.37 |

| Gender = men, n (%) | 61 (58.7) | 126 (67.7) | 0.12 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 29 (27.8) | 63 (34.2) | 0.12 |

| Insulin, n (%) | 8 (7.8) | 22 (12.0) | 0.28 |

| h/o myocardial infarction, n (%) | 31 (30.4) | 42 (22.7) | 0.15 |

| h/o smoking, n (%) | 57 (55.3) | 99 (55.9) | 0.92 |

| Index ICA = symptomatic* ICA, n (%) | 0 (0) | 129 (69.0) | N/A |

| Contralateral ICA occluded, n (%) | 3 (2.9) | 46 (24.6) | <0.001* |

| Contralateral ICA nearly occluded (“string-sign”), n (%) | 4 (3.8) | 12 (6.4) | 0.26 |

| Index ICA PSV, m/s, mean ±SEM [range] |

2.72±0.09 [1.2–5.3] |

2.67±0.08 [1.0–6.9] |

0.18 |

| Index ICA EDV, m/s, mean ±SEM [range] |

0.86±0.37 [0.3–2.5] |

0.91±0.04 [0.2–2.5] |

0.87 |

| Duplex ultrasound index ICA Diameter Stenosis (NASCET,%) mean ±SEM, [range] |

72.0±1.7 [50–89] |

67.5±1.2 [39–86] |

0.10 |

| Computed Tomography index ICA Area Stenosis (%), mean ±SEM, [range], n |

73.0±1.0 [45–91] n=98 |

71.0±0.9 [39–94] n=172 |

0.62 |

| Invasive Quantitative Angiography Diameter Stenosis (NASCET,%), mean ±SEM, [range] |

62.2±0.9 [48–83] |

60.2±0.7 [42–86] |

0.06 |

| Invasive Quantitative Angiography Area Stenosis (%), mean±SEM, [range] |

83.5±0.8 [62–97] |

82.4±0.7 [55–98] |

0.18 |

Independent neurological consultation indicating ipsilateral haemispheric (TIA, stroke) or retinal (amaurosis fugax, retinal stroke) symptoms associated with ≥50% ICA stenosis on at least one non-invasive imaging modality (Duplex Ultrasound – velocity or NASCET criteria, CT angiography).

ICA – Internal Carotid Artery; PSV – Peak Systolic Velocity; EDV – End-Diastolic Velocity; NASCET – North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial method.

Catheter angiography and IVUS acquisition

Selective digital angiography of the index carotid artery was performed with Coroscop or Axiom Artis Zee angiograph (Siemens) in multiple (median 4) angulated projections to define the narrowest lumen diameter while minimizing foreshortening and avoiding overlap of side branches. The view where the stenosis was tightest was used for quantitative measurements (Quantcor QA v5.0, Siemens). Quantitative angiographic measurements were performed by an experienced cardiovascular technologist. Decision on whether to use mechanical embolic protection for IVUS imaging (embolic protection device, EPD) was left to the operator performing the procedure, with all procedures performed by high-volume CAS operators (>75 CAS per year). General criteria for selection of specific EPD type (distal devices – filters, or proximal devices – Gore Flow reversal System or Mo.Ma) have been described previously [19,23,24]. A commercially-available rapid-exchange phased-array IVUS catheter (3.5F, the scanner maximal diameter of 1.17 mm, Avanar F/X, n=41, or Eagle Eye Gold, n=250, Volcano Corp., maximal gray-scale/ChromaFlo imaging field diameter of 14 mm) was introduced to the index ICA over a 0.014 inch coronary guidewire (Balanced Middle Weight or Whisper MS) or, in case of distal EPD use, over the wire of the protective filter. The IVUS scanner was positioned in a non-tapered segment ≈10mm distal to the angiographic plaque. Because eccentric positioning of the transducer tip can influence the diagnostic accuracy of IVUS [17], prior to IVUS imaging gentle manipulation of the guiding catheter and/or the patient’s head positioning were performed to achieve a position of the guidewire and IVUS probe maximally to the center of the lumen. Intracarotid nitroglycerine (100–200 μg) was administered prior to recording. Two IVUS runs were performed with the automatic motorized pullback of 0.5 mm/sec. In addition, a very slow (≈0.2 mm/s) manual pullback was also performed in order not to miss the minimal lumen site due to a non-uniform movement of the IVUS probe with an automatic pullback (i.e., “jumping” of the probe along the plaque) that we realized occurs frequently in the carotid artery. ChromaFlo modality (EndoSonics/Volcano) was used to improve determination of the interface between the lumen (luminal blood flow) and the vessel wall or atherosclerotic plaque [17,25]. In brief, with ChromaFlo real-time images are produced from the scanner at 30 frames per second, and the difference between 2 sequential adjacent frames is detected by computer software producing the color-flow intravascular images, with the movement of echogenic blood particles through the artery demonstrated in red [25]. IVUS measurements of the minimal lumen area (MLA) and distal reference area were performed (3.2.1 Volcano Corp. software) at maximal vessel diastole, and% area stenosis (AS) was calculated. Preliminary evaluation of the IVUS images was performed on-line. After the procedure, the IVUS measurements were repeated by another experienced observer and, in case of differences, a consensus was reached. IVUS measurements were not routinely used to guide the intervention because the interventional guidelines are based on the conventional catheter angiography and/or non-invasive imaging [1,12,15]. However, IVUS is established as the reference technique for vascular imaging [17,21], and in case of significant discrepancies between the non-invasive techniques and invasive angiography determination of lesion severity, the IVUS findings (including the MLA and AS) were reported to the operator and consulting neurologist and could influence decision-making. Such an algorithm was consistent with small prior series that reported IVUS influence on intraprocedural decision-making in ≈10–20% of cases [26].

Heparin was administered during the diagnostic angiography at the initial dose of 100 IU/kg, and was supplemented to maintain the activated clotting time (ACT) between 250 and 300 sec. ACT was closely monitored throughout the procedure not only because some procedures were performed under flow reversal or cessation, but also because it is our experience in filter-protected procedures likewise that optimal anticoagulation is crucial in preventing thromboembolic complications of CAS [24].

Evaluation of complications

Ipsilateral intracranial angiography was performed (through the guiding catheter or sheath) prior to IVUS evaluation, after IVUS evaluation (with the exception of IVUS performed under proximal EPD and followed by immediate CAS), and – if CAS was performed – after CAS. All patients were evaluated by an independent neurologist prior to the procedure, immediately after the procedure and within 24 hours, and prior to hospital discharge. Repeated brain imaging with MRI (preferably) or CT was performed in case of clinical or angiographic complications. Complications were evaluated hierarchically (ie, if more than 1 event occurred, the most severe was indexed) and were defined as follows: carotid artery spasm; carotid artery perforation; EPD intolerance (transient neurological symptoms such as clouded consciousness, aphasia, lateral signs) occurring only while EPD is in use, with immediate and complete symptom(s) resolution upon EPD removal; transient ischaemic attack (TIA, transient episode of neurological dysfunction caused by focal brain or retinal ischaemia, with clinical symptoms lasting usually less than 24 hours – but without evidence of new infarction on brain imaging); stroke (new ischaemic lesion(s) on brain imaging [27], with clinical classification as minor stroke or major stroke according to the NIH stroke scale [minor stroke if NIHSS ≤3]); or death.

The study design was consistent with the quality requirements in evaluating imaging modalities for cerebrovascular diseases [28]. The study protocol was approved by the Jagiellonian University Ethics Committee, and the subjects gave informed written consent.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS 17.0. All continuous variables were evaluated for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Results were expressed as mean ±SEM (range). Differences between groups were analyzed by using a parametric T test or Mann-Whitney test, as required. The categorical data were presented as the numbers and percentage of patients in the groups and were compared by using the χ2 test with the Fisher exact test whenever applicable. All tests were 2-tailed, and the significance level was defined as p<0.05.

Results

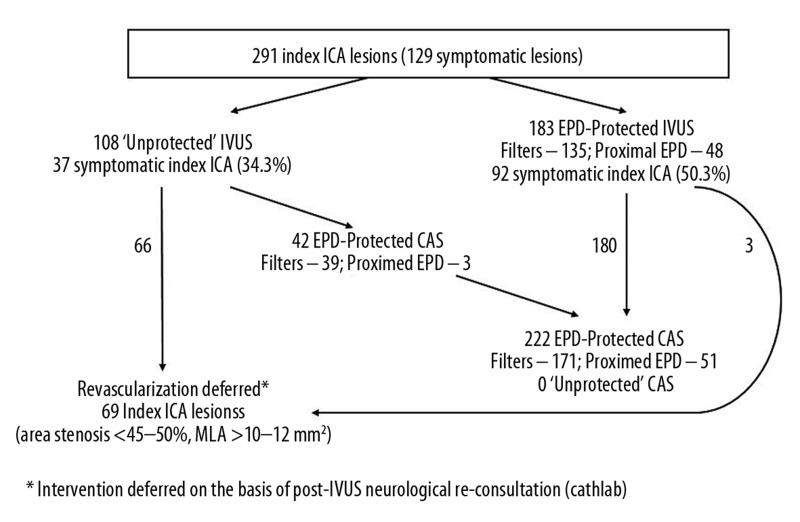

Clinical characteristics of the study group and baseline characteristics of index ICA lesions are shown in Table 1, and Figure 1 displays the study flow with respect to EPD use for IVUS imaging and procedure continuation to CAS vs. CAS deferral. Overall, 291 index arteries were imaged in 291 patients. The symptomatic patients (n=187, 64.3%) had a history of cerebral stroke/retinal embolization (n=131), cerebral TIA (n=77) or transient ocular blindness (n=23). The symptomatic and asymptomatic patients were not different with respect to age, sex, history of myocardial infarction or history of smoking (Table 1). The symptomatic group included a larger proportion of subjects with diabetes (34.2% vs. 27.8%) but the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.12). The contralateral ICA was occluded in 3 asymptomatic patients (3/104, 2.9%) and 46 symptomatic patients (46/187, 24.6%) (p<0.001). Index ICA was the symptomatic carotid vessel in 129 patients in the symptomatic group (69.0%).

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the study flow.

In 12 patients the IVUS run through the initial target lesion was not performed in the symptomatic vessel due to the angiographic stenosis severity (‘string sign’), but it was performed in the contralateral ICA that on non-invasive imaging and catheter angiography had a significant lesion that the neurologist qualified for revascularization. Taken together with the 7 (out of 300 consecutive) patients who could not be included in the IVUS study due to the string-sign stenosis, in a total of 19 (6.3%) of the all-comer CAS population the ICA stenosis severity was considered too high for IVUS imaging. In the asymptomatic patients, index ICA lesions were numerically more severe than in the symptomatic ones by PSV, diameter stenosis on duplex ultrasound, diameter stenosis on catheter angiography, and area stenosis on CT angiography or invasive angiography, but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 1).

Examples of index-ICA IVUS under distal EPD (filter) and proximal EPD (Gore Flow Reversal system) are displayed in Figure 2, and distribution of symptomatic and asymptomatic index-ICA lesion in relation to use of EPD for IVUS imaging is presented in Figure 3. Of the 183 protected IVUS procedures, 135 (73.8%) involved filter-protection (FilterWire – 56, Emboshield – 47, Spider – 15, Accunet – 12, Angioguard – 4, FiberNet – 1) and 48 (26.2%) proximal EPD (Gore Flow Reversal – 29, Mo.Ma – 19), consistent with the concept of proximal EPD-protection for high-risk lesions according to the ‘Tailored CAS’ algorithm [19,23,24]. The fact that index ICA was a symptomatic vessel clearly played a role in the operator’s decision to use EPD for IVUS (Table 2); however, not all symptomatic ICAs were imaged under EPD protection (50.0% symptomatic arteries in the protected IVUS group vs. 34.6% symptomatic index arteries in the unprotected IVUS group, p=0.01, Table 2 and Figure 3). Post-hoc comparison of lesions evaluated by IVUS without EPD vs. under EPD showed preferential EPD use for the more severe lesions by both non-invasive criteria (DUS velocity, DUS NASCET, and CT angiography) and invasive angiography (QA-AD, QA-AS) (p<0.001 for all, Table 2). Quantitative IVUS data confirmed that the lesions imaged under mechanical embolic protection were more severe (MLA 5.57±0.17 vs. 8.62±0.29 mm2, range 1.6–11.1 vs. 4.1–17.4 mm2, p<0.001; AS 73.8±0.8% vs. 61.3±1.25%, range 28.3–93.8% vs. 25.6–80.8%, p<0.001). IVUS-related increase in procedure duration was 7.27±0.19 min (range 2 min 20 sec to 19 min).

Figure 2.

Examples of IVUS acquisition with different types of EPD.

(2-I) shows IVUS acquisition with a distal EPD in a 51-year-old female patient who presented without neurological symptoms, but with a family history of stroke at young age. RICA DUS velocities were 2.7/1.2 m/s and selective carotid artery angiography (A,B) indicated a significant RICA stenosis. Right hemispheric cerebral angiography (C) showed a normal flow to the right hemisphere. A distal EPD (FilterWire EZ, red arrow) was placed in a straight segment of the vessel distal to the lesion (D), and IVUS imaging was performed (E, imaging scanner indicated with white arrow). Index ICA spasm on the protective filter was noted (F) but the flow to the right hemispheric vessels was initially maintained (G) and there was no evidence of IVUS-related cerebral embolization. The ICA spasm, however, was progressive, and after a carotid self-expanding stent (Precise 8.0×40 mm) placement and post-dilatation, the spasm became ICA-occlusive, and this was symptomatic. The symptoms resolved after removal of the filter (whose macroscopic inspection showed limited debris), but a residual spasm was still seen (I); this was treated (J) with intra-arterial injection of nimodipine (200 μg). Post-procedural cerebral angiography showed normal flow to the right hemispheric vessels (K). IVUS mages of the distal reference segment (lumen reference area 17.1 mm2) and MLA (4.6 mm2) are shown in (L). Comparison of pre- and post-procedural MRI showed no evidence of brain injury, and a spasm-related intolerance of the distal EPD was diagnosed.

(2-II) illustrates IVUS acquisition under proximal neuroprotection by flow reversal (tight stenosis of RICA in a 64-year-old man with recurrent transient right eye blindness). Consistent with DUS (RICA flow velocities of 4.5/1.4 m/s), angiography of the right carotid artery showed a tight lesion at the bifurcation (A). There was poor flow to the right hemispheric vessels from RICA (B), and the right anterior cerebral artery did not show (red arrow for the ‘missing’ vessel) from the contrast injection to RICA. In (C), there is contrast medium stagnation following an injection while the low-pressure balloons in the common carotid artery (CCA) and the external carotid artery (ECA) balloons are inflated, causing an intended occlusion of CCA and ECA. When the communication between the guiding catheter lumen and right femoral vein is opened, the flow in the index artery is reversed (green arrow indicates direction of the reversed ICA flow, (D); ‘back’ pressure was 62/48 mmHg and there was optimal tolerance of the temporary flow reversal). The index lesion was crossed under flow reversal (E, F), and IVUS imaging was performed (G). The tight lesion was predilated (H) prior to placing a stent (Xact 8–10×30 mm; in (I) the stent edges indicated with white dots, the stent post-dilatation is shown in (I and J). The final result of the procedure is shown in (K), with normalization of the flow from RICA to the right hemispheric vessels ((L), note that the right anterior cerebral artery, red arrow, is now visible from contrast injection to RICA). IVUS images of the RICA distal reference (lumen area of 28.5 mm2) and the MLA site (4.2 mm2) are shown in (M and N), respectively.

Figure 3.

Distribution of asymptomatic and symptomatic lesions in the unprotected IVUS and EPD-protected IVUS group.

Table 2.

Index ICA characteristics in EPD-unprotected vs. EPD-protected IVUS.

| IVUS without EPD n=108 (37.1%) |

IVUS with EPD n=183 (62.9%) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index ICA = symptomatic ICA, n (%) | 37 (34.3) | 92 (50.3) | 0.01* |

| Index ICA = LICA, n (%) | 54 (50.0) | 104 (56.8) | 0.31 |

| Contralateral ICA occluded, n (%) | 19 (17.6) | 30 (16.4) | 0.745 |

| Index ICA PSV, m/s, mean ±SEM [range] |

2.20±0.08 [1.1–4.6] |

2.97±0.08 [1.1–6.9] |

<0.001* |

| Index ICA EDV, m/s, mean ±SEM [range] |

0.69±0.03 [0.3–1.6] |

1.00±0.04 [0.6–2.5] |

<0.001* |

| Duplex ultrasound index ICA Diameter Stenosis (NASCET,%) mean ±SEM, [range] |

65.1±1.7 [39–89] |

71.5±1.2 [46–87] |

0.002* |

| Computed Tomography index ICA area stenosis (%), mean ±SEM, [range], n |

67.0±1.1 [30–86] n=101 |

74.52±0.8 [40–94] n=169 |

<0.001* |

| Invasive Quantitative Angiography Diameter Stenosis (NASCET,%), mean ±SEM, [range] |

55.1±0.7 [42–82] |

64.2±0.7 [46–86] |

<0.001* |

| Invasive Quantitative Angiography Area Stenosis (%), mean ±SEM, [range] |

77.7±0.6 [58–94] |

85.7±0,5 [55–98] |

<0.001* |

EPD – cerebral Embolic Protection Device; ICA – Internal Carotid Artery; PSV – Peak Systolic Velocity; EDV – End-Diastolic Velocity; NASCET – North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial metod [20].

As it is not feasible to separate, with certainty, the periprocedural complications that have a causal association with IVUS imaging from those resulting from different procedural steps (eg, guiding catheter placement or EPD insertion or [in procedures including stenting] the lesion predilatation, stent deployment or stent post-dilatation, or EPD removal), our analysis involved all complications that occurred in procedures that included IVUS. Table 3 shows the prevalence of ICA spasm, ICA perforation, EDP intolerance, TIA, minor stroke, major stroke, and death in the 3 study groups – (1) unprotected IVUS and no CAS (n=66), (2) unprotected IVUS followed by CAS (n=42, CAS always under EPD; in this group filter-protection in 39, flow blockade in 2, flow reversal in 1), and (3) EPD-protected IVUS followed by CAS (n=183; this group includes 3 patients with index-ICA imaging under EPD but no CAS due to lack of IVUS-evidence of area stenosis exceeding 45–50% and a wide minimal lumen area). No ICA perforation or dissection, and no major stroke or death occurred in any of the study groups. In the group of unprotected IVUS not followed by CAS there was only 1 adverse event (1.5%, TIA, no angiographic evidence of cerebral embolization and no MRI evidence of new ischaemic lesion) (Table 3). In the group of 42 unprotected ICA-IVUS procedures followed by (in all cases EPD-protected) CAS, there were 2 instances (4.8%) of asymptomatic ICA spasm on filter, 1 case of EPD intolerance (symptomatic ICA spasm on filter), 2 TIAs (transient aphasia occurring 2 hours after the procedure and dyscalculia within the first 2 post-procedural days, no new lesions on repeated brain imaging in either case), and 1 minor stroke (NIH-SS=2). In the group of EPD-protected IVUS followed by CAS (n=183 for IVUS, n=180 for subsequent CAS), ICA spasm on filter occurred in 7 cases (3.8%) and EPD intolerance was seen in 8 patients (4.4%; in 2 cases – ICA stop-flow on filter, in 6 – intolerance of proximal EPD occurring at the stage of stenting and post-dilatation). There were 5 TIAs (symptom resolution within 24 hours, no new brain lesions) and 4 minor strokes (NIH-SS≤3) in the EPD-protected IVUS followed by CAS group; all occurred in filter-protected procedures. This included 1 event initially classified as a reversible intermittent neurological deficit (the patient left the hospital asymptomatic) that was re-classified as minor stroke due to a new ischemic lesion on cerebral CT, and 1 asymptomatic embolization of a MCA M3 branch with a new ischaemic lesion on cerebral MRI.

Table 3.

Periprocedural complications in ‘unprotected’ index ICA IVUS not followed by CAS, ‘unprotected’ IVUS followed by CAS and ‘protected’ index ICA IVUS followed by CAS (CAS was always under embolic protection).

| Unprotected IVUS [n=108] | Protected IVUS followed by CAS* [n=183] filters =140 proximal EPD =43 |

Total [n=291] |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CAS [n=66] |

IVUS followed by CAS* [n= 42] filters =39 proximal EPD =3 |

|||

| ICA spasm | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.8%)# | 7 (3.8%)# | 9 (3.1%)# |

| ICA perforation | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| EPD intolerance*** | N/A | 1 (2.4%) | 8 (4.4%)‡ | 9/225 (4.0%) |

| TIA† | 1 (1.5%) | 2 (4.8%) | 5 (2.7%) | 8 (2.7%) |

| minor stroke | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.4%) | 4 (2.1%)### | 5 (1.7%) |

| major stroke | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| death | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

N/A – not applicable.

In n=3 cases EPD (filter)-protected IVUS was not followed by CAS due to area stenosis <50% (intraprocedural neurological re-consultation);

No ICA spasm occurred in response to ICA wiring or IVUS run; all spasms were related to distal EPD (filter) use for IVUS protection and/or CAS;

Transient neurological symptoms (such as clouded consciousness, aphasia, lateral signs) occurring only while EPD was in use, with complete, immediate symptom(s) resolution after EPD removal;

In n=2 cases due to filter blockade with ICA stop-flow (filter basket filled with debris); in n=6 cases proximal EPD intolerance;

Neurological symptoms lasting typically <24h (in one case 38h – previously classified as RIND) and without new lesions on brain imaging (repeated brain imaging mandatory in case of symptoms) [27];

in n=1 case intracranial embolization (limited to a branch of the middle cerebral artery M3) that occurred already at the diagnostic stage prior to IVUS imaging (i.e., was present in the diagnostic intracranial angiogram prior to index ICA wiring); clinical symptoms resolved within 4 hours but MRI showed a new ischemic lesion that co-localized with the embolized branch.

Thus the periprocedural strokes were limited to minor strokes, and those occurred only in the procedures with CAS (2.3% vs. 0% in those without CAS; as the overall event rate was low, the difference did not reach statistical significance, p=0.28, Table 3). For the 8 TIAs and 5 (minor) periprocedural strokes (all in the procedures with stent placement (Table 3)), no difference could be detected for the complication risk by the ICA symptomatic status (TIA – 4/162 vs. 4/129, p=0.61; stroke – 3/162 vs. 2/129, p=0.75; 162 asymptomatic vs. 129 symptomatic ICA lesions).

Discussion

This is the first prospective study of carotid artery IVUS safety in an all-comer population referred for CAS, and it includes a high proportion (64.3%) of symptomatic patients. More than one-third of arteries were imaged with IVUS without an EPD, and nearly one-third (ie, high-risk lesions) were imaged under proximal neuroprotection by flow reversal or flow clamping. With intracranial angiography performed routinely before and after IVUS, there was no evidence for IVUS-triggered cerebral embolization. Stenting was deferred in 69/291 cases (23.7%). Periprocedural strokes were limited to minor strokes; those occurred only in the procedures with stent placement and were limited to procedures with distal EPD neuroprotection (total stroke rate of 2.4% in the CAS group). IVUS increased the procedure duration by an average of 7 minutes. Thus, in an unselected population with significant ICA stenosis, we found that the native carotid plaque IVUS is feasible (unless ‘string-sign’ stenosis severity would require predilatation prior to the IVUS transducer insertion) and that it is safe. We also showed that IVUS imaging of less severe lesions may not require mandatory mechanical protection, while the high-risk lesions can be safely evaluated with IVUS under proximal neuroprotection by flow clamping/reversal.

IVUS vs. duplex ultrasound

In-plane resolution of the most widely used carotid artery imaging technique, DUS (linear probe of 5 to 12 MHz) can reach ≈300–600×300–600 μm [30], which is similar to the resolution of typical MRI (≈600 x 600μm in-plane) but is lower than the resolution of 64-row CT (≈300×300 μm in-plane). There have been attempts to use the 2-dimensional DUS technique to evaluate structures as thin as the carotid plaque fibrous cap (measurement threshold of ≈650 μm) [30], but several major limitations exist. In particular, DUS imaging is affected by the artifacts from tissue interfaces in the way of the ultrasound beam, acoustic shadowing by highly fibrotic or calcified structures, and dependence on the angle of insonation (imaging and measurements are optimal with the ultrasound beam perpendicular to the tissue interface) [30]. Moreover, there is evidence that DUS measurements vary widely between laboratories, and the magnitude of the variation is clinically important as it affects decisions on patient management [31–33]. Evaluation of the conventional DUS velocity criteria in relation to catheter angiography in over 1000 carotid arteries showed that while DUS tends to over-estimate the stenosis degree, it generally fails in differentiating stenoses less than 70% where the agreement between DUS and angiography is only 45% [34]. This finding has been confirmed in a more recent meta-analysis of over 1400 individual patient data, which showed that in patients with a 50–69% stenosis DUS was indeed more likely to give a misdiagnosis than correct diagnosis of the stenosis severity [35]. In addition, stenosis evaluation by velocity criteria can be affected by the vessel diameter [36]. While computer-assisted analysis of ultrasonic plaque echolucency (Gray Scale Median, GSM) was initially expected to help in stratifying carotid bifurcation lesions according to stroke risk, a recent study showed that a low GSM was not practical in discriminating patients with stroke risk (GSM <35 seen in 27.8% subjects with stroke vs. 16.7% without brain infarction) [37].

IVUS provides a 3-dimensional image from inside the vascular lumen; it enables characterization of the vessel wall and atherosclerotic plaque with resolution significantly greater than that of non-invasive techniques. Image resolution is dependent on the wave frequency, and current scanners use frequencies in the range of 10 to 40 MHz. The higher frequencies provide higher resolutions, but this occurs at the cost of decreased field of view and depth of penetration [17]. IVUS scanner frequencies of 20 and 40 MHz are used for iliac and cardiac vessels, and we are currently using the 20 MHz catheter for carotid artery imaging. With the flow-coding (ChromaFlo) modality, the imaging field diameter of a 20-MHz intravascular scanner is 14 mm [21]; thus it is sufficient for imaging the carotid artery lumen whose diameter is ≈4.5–5.5 mm and, in most cases, the carotid artery wall (media-to-media). The resolution of the 20-MHz IVUS scanner has been studied in detail in a purpose designed micro-wire phantom model by Engeler et al. [16], who, using a rotational IVUS catheter with a 3-cycle pulse, found the axial (ie, along the ultrasound beam) resolution to be at least 120 μm. However, with the new phased-array multi-element transducers (such as the one used in our study), an improved axial resolution (reaching 80 μm) has been reported [17]. These parameters make IVUS imaging unparalleled in vascular imaging in terms of an optimal compromise between resolution and tissue penetration.

Classification of complications

A report on complications in 2207 IVUS procedures in the evaluation of coronary artery disease, with data pooled from 28 institutions (mean case load of 79 procedures per center) [38], attempted to elucidate the cause-and-effect association between IVUS imaging and procedural complications. This was assessed each time by the operator performing the procedure according to the following 3 categories – (1) ‘certain relation to IVUS’ (when the relation was temporal and presumed to be causative), (2) ‘not related to IVUS’ (when the event could clearly be attributed to procedures other than IVUS), or (3) ‘uncertain relation to IVUS’ (when the event could have been caused by IVUS, by another procedure, or potentially occur randomly) [38]. In our study, this classification was not used due to the following reasons. First, such a classification is always subjective (even if achieved by a consensus of experts rather than the opinion of separate operators who might evaluate a similar event differently) and can be prone to significant interpretation errors. For instance, ICA spasm on a protective filter used for CAS, with IVUS imaging prior to placing the stent, could be labeled as: ‘IVUS-related’ (because it occurred during the IVUS run that increased the duration of keeping the filter open in ICA), ‘IVUS-unrelated’ (because spasms on filters occur irrespective of IVUS), or as having an ‘uncertain relation’ to IVUS. Second, the 3 subgroups of our procedures involving the IVUS imaging in 3 different scenarios (EPD-unprotected IVUS not followed by CAS, unprotected IVUS followed by EPD-protected CAS, and EPD-protected IVUS followed by EPD-protected CAS) are difficult to compare. Therefore, in the present study all periprocedural complications that occurred with procedures involving IVUS were considered as potentially related to IVUS and were reported. The angiographic events were evaluated by 2 CAS operators and a radiologist, and the clinical events were evaluated by an independent neurologist. This methodology of complication reporting is likely to over-estimate the actual complications of IVUS imaging.

The present work differentiated periprocedural TIA from EPD intolerance. Although both have a similar clinical picture, their separation, we believe, is important as it avoids confusion seen in a number of studies that have reported on CAS-related complications. The present study defined EPD intolerance as transient neurological symptoms (such as clouded consciousness, aphasia, or lateral signs) occurring only while EPD is in use, with immediate and complete symptom(s) resolution upon EPD removal. In contrast, the symptoms of TIA preceded EPD insertion, exceeded the EPD removal, or occurred after the procedure. For the tentative diagnoses of EPD intolerance or TIA, presence of new ischaemic lesions on brain imaging lead to automatic event re-classification as a “stroke”, consistent with the increasing adoption of the recently changed stroke definition [27]. This, taken together with the fact that periprocedural TIA may be unrelated to focal brain ischaemia (but reflect temporal alterations in neurological status in reaction to, for instance, the contrast medium or changes in blood pressure) is likely to overestimate in our report the rate of transient neurological deficit that might occur as a result of IVUS imaging. Nevertheless, the overall complication rate was low (Table 3) indicating that, in experienced hands, carotid IVUS is safe.

Risk of IVUS imaging in relation to diagnostic angiogram risk

Large data series and meta-analyses indicate that, in patients with carotid artery stenosis, the rates of permanent neurological complications of carotid artery angiography are in the range of 0.5–0.63%, while transient neurological complications occur at 1.3–1.8% [13,39,40]. There is also evidence that experience of the operator plays an important role, with the overall neurological complication rate of diagnostic angiography reduced by over 50% when the study is performed by an experienced operator (0.5% vs. 1.3%) [40]. In the present study, the risk of diagnostic carotid angiogram combined with IVUS was associated with 0% risk of permanent neurological deficit and 1.5% risk of transient neurological deficit; the risk was higher only if the diagnostic imaging was combined with the stenting procedure (Table 3). Carotid artery IVUS imaging was associated with an increase in the procedure duration time by an average of 7 minutes; this, however, had no major bearing on the total procedural time of diagnostic carotid/cerebral angiogram (≈15–20 min) or carotid/cerebral angiogram and CAS (≈30–50 min).

Intraprocedural IVUS imaging in relation to the risk of CAS

Analysis of periprocedural complications in 627 CAS procedures by Verzini et al. [40] considered the following steps of the procedure: (i) target vessel catheterization and angiogram, (ii) EPD insertion, (iii) stenting (including lesion predilatation, if performed, and stent post-dilatation) and EPD removal, (iv) early post-interventional phase, and (v) late post-interventional phase. With an almost exclusive use of distal EPDs, these authors reported a major stroke/death incidence of 1.75% and minor stroke incidence of 2.9%. Verzini et al. [40] also found that 40% of major strokes could not be prevented by EPD because those had already occurred at the target vessel catheterization or angiogram phase. Moreover, that study showed a reduced complication rate in the fourth vs. first interval of the study period, consistent with the “protective” role of increasing experience of the operators [40]. More recent analysis of 1176 CAS procedures performed according to the ‘tailored’ CAS algorithm (proximal EPD in 31.4%) showed a rate of major stroke/death of 0.68% and minor stroke rate of 1.70% (total death/stroke rate of 2.38%), with 2/3 strokes occurring outside the time-frame of EPD being “active” [24]. Data from the present study, incorporating IVUS into the ‘tailored CAS’ algorithm, show no major stroke/death, minor stroke rate of 2.25%, and the total death/any stroke rate of 2.25% (proximal EPD use in almost 1 in 3 CAS procedures), clearly indicating that IVUS imaging does not increase the CAS procedural risk. Clark et al. [41], who were not able to take advantage of proximal neuroprotection, found that in 18% of carotid artery lesions (19/107) the perceived risk of IVUS imaging was too high to attempt lesion-crossing with the IVUS catheter. This is in contrast to our data that (with a considerable rate of proximal EPD use) showed IVUS deterring in only 6.3% of arteries (‘string-sign’ lesions in all). Indeed, our work shows that the majority of high-risk ICA lesions can be safely imaged under a proximal EPD (example in Figure 2-II).

Previous work on IVUS risk in the coronary and carotid territory

Multi-center analysis of 2207 coronary procedures with IVUS imaging (diagnostic imaging – 41%, drug testing – 11%, intracoronary intervention guidance – 48%) reported coronary spasm during IVUS imaging in 2.9% [38]. In that series, there were 9 (0.4%) complications other than spasm that were classified as having a ‘certain’ relation to IVUS (5 occlusions, 2 dissections, 1 embolism, and 1 thrombus), and a further 14 events (0.6%, including 5 acute occlusions and 3 dissections) classified as having an ‘uncertain’ relation to IVUS. In another study, coronary spasm occurred in 1.9% of the 525 coronary IVUS procedures [42]. When angiographic and IVUS imaging was repeated at 18–24 months, an increase in lesion severity or new lesion occurrence was found in 11.6% of IVUS-related arteries vs. 9.8% of non-IVUS-related arteries (p=0.84), providing no evidence of an ‘instrumented vessel’ effect with IVUS imaging [42]. In a prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis that involved 3-vessel IVUS imaging in 697 patients with an acute coronary syndrome, 11 patients (1.6%) had complications attributed to IVUS imaging (10 dissections and 1 perforation) [18]. This is not surprising, since any urgent or emergent procedure is associated with an increased risk of complications, and the complication rate in coronary procedures involving IVUS was found to have a ‘gradient’ from interventions in acute coronary syndromes (2.1%) to elective interventions (1.9%) and diagnostic IVUS imaging (0.0–0.6%) [38]. In the present study no carotid artery perforation occurred, and we noted no carotid artery spasm other than that on filters (Table 3), which led to EPD intolerance in 2 cases.

Prior data on safety of carotid artery imaging with IVUS are very limited, as most reports refer to (i) patient series of less than 30 subjects [26,43–46], (ii) IVUS imaging limited to ‘non-significant’ lesions [43,44], or (iii) IVUS imaging with routine (and thus far distal-only) neuroprotection [26,41]. Räsänen et al. [43] described carotid IVUS imaging in 27 patients without significant carotid artery stenosis (17% mean diameter stenosis, <10% stenosis in 13 lesions, >20% stenosis in 14 lesions), reporting no complications or adverse effects. A later report from the same group described non-complicated IVUS imaging in 29 atherosclerotic ICA lesions with a mean diameter stenosis of 35% (4–40%). Clark et al. [41] who used IVUS during the procedure of stenting 87 carotid artery lesions (in 20% post-CEA restenotic lesions), reported 1 carotid artery perforation (0.9%), and found than in 9% of cases IVUS affected intraprocedural decision-making. While more research is definitely needed, the present data suggest that IVUS findings can influence the CAS procedure at 2 key steps – first, at the level of decision for interventional vs. medical-only management, and secondly, with regard to stent post-dilatation with a larger-diameter balloon. While aggressive stent post-dilatation may lead to increased risk of embolization through the “cheese-grater” effect [19], reaching an optimal in-stent area may be critical in preventing carotid in-stent stenosis [47]. In the study by Clark et al. [41], IVUS identification of superficial lesion calcification was associated with an increased risk of periprocedural stroke (31% vs. 1%, p<0.001; total death/stroke 5.6%, total stroke 4.7%, minor stroke 2.8%), but there was only 7% adoption of EPD use and the EPD types were limited to a distal filter. More recently, Diethrich et al. [45] evaluated 30 carotid artery lesions using IVUS (23% post-CEA restenotic lesions). All procedures were performed under a distal EPD (Accunet filter), and in 15 patients the IVUS data were used to validate the “virtual histology” (VH) software against conventional histology of CEA specimens, with no complications mentioned in the study report. A post-hoc report of CAS with and without intraprocedural IVUS by Bandyk and Armstrong [46] indicated that IVUS imaging resulted in the use of larger diameter balloons for stent post-dilatation. The 30-day stroke incidence was 1.8% in the IVUS group and 0.0% in the angio-only group, but this retrospective analysis of non-consecutive patients did not involve any secondary imaging such as intracranial angiography as this was not routinely performed in a series not designed to test the safety of IVUS. Two pilot studies (n=18 and n=24 subjects) [26,47] have recently reported that application of the radiofrequency IVUS analysis (VH) might affect CAS intraprocedural decision-making, but large-scale data are needed, particularly as only a poor correlation between VH-IVUS plaque characteristics and the degree of cerebral embolization during CAS was initially suggested [46].

Our data indicate that diagnostic IVUS imaging is safe (even if IVUS is acquired by an experienced-operator decision without EPD) and the risk of complications occurs when the carotid interventional procedure (stenting) is performed (Table 3).

Limitations

By decision of the operators, in 6.3% ICA lesions IVUS imaging was not acquired because of the unacceptably high risk of mobilizing plaque material (thus provoking distal embolization) in very tight index ICA lesions (“string sign”, 95%–99% stenosis). The maximal diameter of the intravascular scanner that we used was 1.17mm, thereby limiting intravascular imaging to lesions that could be crossed with the transducer with a smooth passing. Indeed, it is well-known that an IVUS catheter larger than practicable for the lumen may fail to cross the stenotic lesion or, if forced, can cause mechanical disruption of the plaque and distal embolization [21]. This limitation is unlikely to have any major impact of the findings in our study as – in contrast to previous reports in significantly smaller populations – we did not refrain from high-risk lesion imaging with IVUS. Consistent with our ‘tailored CAS’ algorithm [19,23,24,29,48], high-risk lesion IVUS imaging was performed under proximal EPD (example in Figure 2). Lesion crossing with distal EPD (during the EPD insertion) is known to be associated with risk of embolization [49], and evidence is increasing that distal-filter EPDs can be significantly less effective than the proximal systems in preventing embolization during CAS [50–52]. Indeed, the high rate of proximal EPD use in this study (26.2%) is consistent with the overall proportion of proximal EPD use in our center [19,23,24,29,53] and it might have contributed significantly to the low level of complications.

Transcranial Doppler has been shown to have a role in evaluating spontaneous embolization from the carotid plaque [9,55], and we did consider employing transcranial Doppler to register microembolic signals (MES) during the carotid procedures involving IVUS imaging. However, consistent with previously published data [55], our pilot analysis indicated that MES can be commonly registered with contrast and saline injections. This might limit the applicability of transcranial Doppler in any quantitative evaluation of IVUS-related microembolization in procedures involving IVUS imaging without EPD or under different EPD types (ICA retrograde flow or flow cessation vs. distal filter-protection with maintained antegrade flow).

In our study population of nearly 300 subjects we were unable to perform routine brain imaging with MRI before and after IVUS acquisition. Although during the course of our study MRI has become the preferred imaging modality in diagnosing ischaemic brain injury [27], many patients presented with CT imaging on CAS referral (all patients had either brain CT or brain MRI scan prior to the index ICA IVUS imaging). In those with CT imaging performed on an outpatient basis prior to hospital admission, we were unable to justify the MRI scan. The patients with any periprocedural neurological complication (including transient EPD intolerance) had post-procedural brain imaging with the same modality as their pre-procedural imaging to enable comparison of the images with respect to new ischaemic lesions. This imaging protocol was consistent with the idea that although MRI may be more accurate than CT for the detection of ischaemic brain lesions, the use of MRI for periprocedural stroke determination needs to take into consideration practicality and cost-effectiveness [56].

Our study did not involve diffusion-weighted MRI imaging (DWI), which is known to be very sensitive in detecting peri-procedural brain injury [57]. However, there is evidence that DWI lesions are identified in a majority (≈70%) of CAS procedures [47,57,58] and, more importantly, that in ≈50% of CAS subjects new DWI lesions are seen in both hemispheres [47]. This makes DWI imaging impractical in searching for IVUS-related lesions in a real-world registry setting, since the protocol would then require interrupting each procedure immediately after IVUS to subject the patient to DWI (in contrast, we were able to perform the intracranial angiogram immediately before and after IVUS imaging). Moreover, there is evidence that the new brain lesions detected with DWI after CAS or CEA do not affect cognitive performance in a manner that is long-lasting or clinically relevant [58].

Finally, consistent with our routine management [19], all study subjects were pre-treated with a statin – a therapy shown to stabilize the vulnerable coronary and carotid plaques [59,60]. Thus we could not assess the potential effect of statin pre-treatment on increasing the safety of IVUS.

Conclusions

In the largest carotid IVUS study to date, including unselected patients referred for carotid artery revascularization, we found that in a high-volume center carotid IVUS is safe. For less severe lesions, IVUS imaging may not require mandatory mechanical protection, whereas high-risk lesions can be safely imaged with IVUS under proximal neuroprotection by ICA flow reversal or ICA flow clamping. Further work is needed to evaluate the potential role of IVUS in decision-making in borderline carotid lesions and to test whether characterization of the plaque morphology with IVUS can play a role in stroke risk stratification.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Justyna Stefaniak of Data Management and Statistical Analysis, Cracow, for data management and statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

Source of support: This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Poland [N402184234], Polish Cardiac Society/Servier (2007) and Polish Cardiac Society/Adamed (2008)

References

- 1.Goldstein LB, Bushnell CD, Adams RJ, et al. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:517–84. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3181fcb238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mead GE, Murray H, Farrell A, et al. Pilot study of carotid surgery for acute stroke. Br J Surg. 1997;84:990–92. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800840723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hackam DG, Kapral MK, Wang JT, et al. Most stroke patients do not get a warning: A population-based cohort study. Neurology. 2009;73:1074–76. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b9c8e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White CJ, Beckman JA, Cambria RP, et al. Atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease symposium II: Controversies in carotid artery revascularization. Circulation. 2008;118:2852–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roffi M, Spence JD. Is there a role for revascularisation in asymptomatic carotid stenosis? A Pro – Con debate. Brit Med J. 2010;341:584–85. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Streifler JY. Asymptomatic carotid stenosis: Intervention or just stick to medical therapy – the case for medical therapy. J Neur Transm. 2011;118:637–40. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0590-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein AE, Solomon GG, Hamel MB. Management of carotid stenosis – Polling results. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:e23–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMclde0801712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calonge N, Petti DB, DeWitt TG, et al. Screening for carotid artery stenosis: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:854–59. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-12-200712180-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markus HS, King A, Shipley M, et al. Asymptomatic embolisation for prediction of stroke in the Asymptomatic Carotid Emboli Study (ACES): A prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:663–71. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70120-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halliday A, Harrison M, Hayter E, et al. 10-year stroke prevention after successful carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic stenosis (ACST-1): A multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1074–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61197-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derdeyn CP. Carotid stenting for asymptomatic carotid stenosis: trial it. Stroke. 2007;38(Suppl2):715–20. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000249395.98417.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al. 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS Guideline on the management of patients with extracranialcarotid and vertebral artery disease. Stroke. 2011;42:e420–63. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182112d08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh N, Moody AR, Gladstone DJ, et al. Moderate carotid artery stenosis: MR imaging-depicted intraplaque hemorrhage predicts risk of cerebrovascular ischemic events in asymptomatic men. Radiology. 2009;252:502–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2522080792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao X, Underhill HR, Zhao Q, et al. Discriminating carotid atherosclerotic lesion severity by luminal stenosis and plaque burden: a comparison utilizing high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging at 3.0 Tesla. Stroke. 2011;42:347–53. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.597328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liapis CD, Bell PR, Mikhailidis D, et al. ESVS guidelines. Invasive treatment for carotid stenosis: indications, techniques. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37(Suppl 4):1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engeler CE, Ritenour ER, Amplatz K. Axial and lateral resolution of rotational intravascular ultrasound: in vitro observations and diagnostic implications. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1995;18:239–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00239419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JT, White RA. Basics of intravascular ultrasound: an essential tool for the endovascular surgeon. Semin Vasc Surg. 2004;17:110–18. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:226–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pieniazek P, Musialek P, Kablak-Ziembicka A, et al. Carotid artery stenting with patient- and lesion-tailored selection of the neuroprotection system and stent type: early and 5-year results from a prospective academic registry of 535 consecutive procedures (TARGET-CAS) J Endovasc Ther. 2008;15:249–62. doi: 10.1583/07-2264.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicolaides AN, Shifrin EG, Bradbury A, et al. Angiographic and duplex grading of internal carotid stenosis: can we overcome the confusion? J Endovasc Surg. 1996;3:158–65. doi: 10.1177/152660289600300207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ota H, Takase K, Rikimaru H, et al. Quantitative vascular measurements in arterial occlusive disease. Radiographics. 2005;25:1141–58. doi: 10.1148/rg.255055014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gruszczynska K, Baron J, Zielinski Z, et al. Cerebral circulation insufficiency – correlation of CTA-visualized atherosclerotic lesions in extra- and intracranial arteries. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10(Suppl 3):71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pieniazek P, Musialek P, Dzierwa K, et al. Flow reversal for proximal neuroprotection during endovascular management of critical symptomatic carotid artery stenosis coexisting with ipsilateral external carotid artery occlusion. J Endovasc Ther. 2009;16:744–51. doi: 10.1583/09-2867.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pieniazek P, Musialek P, Tekieli L, et al. Carotid artery stenting according to the ‘Tailored CAS’ algorithm is associated with a low 30-day complication rate: Data from the continued TARGET-CAS study. Pol Heart J. 2012 (in press) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zacharatos H, Hassan AE, Qureshi AI. Intravascular ultrasound: principles and cerebrovascular applications. Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:586–97. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joan MM, Moya BG, Agustí FP, et al. Utility of intravascular ultrasound examination during carotid stenting. Ann Vasc Surg. 2009;23:606–11. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals. Stroke. 2009;40:2276–93. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qureshi AI. A new scheme for grading the quality of scientific reports that evaluate imaging modalities for cerebrovascular diseases. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13(10):RA181–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pieniazek P, Musialek P, Tekieli L, et al. The role of proximal neuroprotection by flow reversal in high-risk carotid artery stenting. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(Abstract Suppl):511. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devuyst G, Karapanayiotides T, Ruchat P, et al. Ultrasound measurement of the fibrous cap in symptomatic and asymptomatic atheromatous carotid plaques. Circulation. 2005;111:2776–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.483024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jahromi AS, Cinŕ CS, Liu Y, Clase CM. Sensitivity and specificity of color duplex ultrasound measurement in the estimation of internal carotid artery stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:962–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mead GE, Lewis SC, Wardlaw JM. Variability in Doppler ultrasound influences referral of patients for carotid surgery. Eur J Ultrasound. 2000;12:137–43. doi: 10.1016/s0929-8266(00)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qureshi AI, Suri MF, Ali Z, et al. Role of conventional angiography in evaluation of patients with carotid artery stenosis demonstrated by Doppler ultrasound in general practice. Stroke. 2001;32:2287–91. doi: 10.1161/hs1001.096613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabeti S, Schillinger M, Mlekusch W, et al. Quantification of internal carotid artery stenosis with duplex US: comparative analysis of different flow velocity criteria. Radiology. 2004;232:431–39. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2321030791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chappell FM, Wardlaw JM, Young GR, et al. Carotid artery stenosis: accuracy of noninvasive tests – individual patient data meta-analysis. Radiology. 2009;251:493–502. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2512080284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mysior M, Stefanczyk L. Doppler ultrasound criteria of physiological flow in asymmetrical vertebral arteries. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13(Suppl 1):73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Falkowski A, Kaczmarczyk M, Cieszanowski A, et al. Computer-assisted characterisation of a carotid plaque. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10(Suppl 3):67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hausmann D, Erbel R, Alibelli-Chemarin MJ, et al. The safety of intracoronary ultrasound. A multicenter survey of 2207 examinations. Circulation. 1995;91:623–30. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willinsky RA, Taylor SM, TerBrugge K, et al. Neurologic complications of cerebral angiography: prospective analysis of 2899 procedures and review of the literature. Radiology. 2003;227:522–28. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272012071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verzini F, Cao P, De Rango P, et al. Appropriateness of learning curve for carotid artery stenting: an analysis of periprocedural complications. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:1205–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clark DJ, Lessio S, O’Donoghue M, et al. Safety and utility of intravascular ultrasound-guided carotid artery stenting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004;63:355–62. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guédčs A, Keller PF, L’Allier PL, et al. Long-term safety of intravascular ultrasound in nontransplant, nonintervened, atherosclerotic coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;15(45):559–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Räsänen HT, Manninen HI, Vanninen RL, et al. Mild carotid artery atherosclerosis: assessment by 3-dimensional time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography, with reference to intravascular ultrasound imaging and contrast angiography. Stroke. 1999;30:827–33. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.4.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berg MH, Manninen HI, Räsänen HT, et al. CT angiography in the assessment of carotid artery atherosclerosis. Acta Radiol. 2002;43:116–24. doi: 10.1080/028418502127347763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diethrich EB, Margolis PM, Reid DB, et al. Virtual histology intravascular ultrasound assessment of carotid artery disease: the Carotid Artery Plaque Virtual Histology Evaluation (CAPITAL) study. J Endovasc Ther. 2007;14:676–86. doi: 10.1177/152660280701400512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bandyk DF, Armstrong PA. Use of intravascular ultrasound as a “Quality Control” technique during carotid stent-angioplasty: are there risks to its use? J Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;50:727–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Timaran CH, Rosero EB, Martinez AE, et al. Atherosclerotic plaque composition assessed by virtual histology intravascular ultrasound and cerebral embolization after carotid stenting. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:1188–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.05.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Musialek P, Pieniazek P. Restenosis after carotid artery stenting versus endarterectomy: The jury is still out! J Endovasc Ther. 2010;17:271–72. doi: 10.1583/09-2961.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Mubarak N, Roubin GS, Vitek JJ, et al. Effect of the distal-balloon protection system on microembolization during carotid stenting. Circulation. 2001;104:1999–2002. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.099224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidt A, Diederich KW, Scheinert S, et al. Effect of two different neuroprotection systems on microembolization during carotid artery stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1966–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schönholz C, Karthikeshwar K, Welzig C, et al. Transcranial doppler monitoring during carotid artery stenting: Comparison between flow reversal and filter for cerebral protection. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(Suppl D):20D. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clair DG, Hopkins LN, Mehta M, et al. Neuroprotection during carotid artery stenting using the GORE flow reversal system: 30-day outcomes in the EMPiRE Clinical Study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;77:420–29. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dzierwa K, Pieniazek P, Musialek P, et al. Treatment strategies in severe symptomatic carotid and coronary artery disease. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17(8):RA191–97. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abbott AL, Chambers BR, Stork JL, et al. Embolic signals and prediction of ipsilateral stroke or transient ischemic attack in asymptomatic carotid stenosis. A multicenter prospective registry. Stroke. 2005;36:1128–33. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000166059.30464.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Waigand J, Gross CM. Carotid stent placement prior to coronary angioplasty or coronary bypass graft surgery. Curr Interv Cardiol Rep. 2001;3:117–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brazzelli M, Sandercock PA, Chappell FM, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging versus computed tomography for detection of acute vascular lesions in patients presenting with stroke symptoms. Stroke. 2010;41:e427–28. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007424.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bonati LH, Jongen LM, Haller S, et al. New ischaemic brain lesions on MRI after stenting or endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis: a substudy of the International Carotid Stenting Study (ICSS) Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:353–62. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wasser K, Pilgram-Pastor SM, Schnaudigel S, et al. New brain lesions after carotid revascularization are not associated with cognitive performance. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu Dan-Qing, Lin Shu-Guang, Chen Ji-Yan, et al. Effect of atorvastatin therapy on borderline vulnerable lesions in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:433–39. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2011.23408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao XQ, Dong L, Hatsukami T, et al. MR imaging of carotid plaque composition during lipid-lowering therapy a prospective assessment of effect and time course. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2011;4:977–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]