Abstract

Objectives

To first, validate in English hospitals the internal structure of the ‘Patient Evaluation of Emotional Care during Hospitalisation’ (PEECH) survey tool which was developed in Australia and, second, to examine how it may deepen the understanding of patient experience through comparison with results from the Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire (PPE-15).

Design

A 48-item survey questionnaire comprising both PEECH and PPE-15 was fielded. We performed exploratory factor analysis and then confirmatory factor analysis using a number of established fit indices. The external validity of the PEECH factor scores was compared across four participating services and at the patient level, factor scores were correlated with the PPE-15.

Setting

Four hospital services (an Emergency Admissions Unit; a maternity service; a Medicine for the Elderly department and a Haemato-oncology service) that contrasted in terms of the reported patient experience performance.

Participants

Selection of these acute service settings was based on achieving variation of the following factors: teaching hospital/district general hospital, urban/rural locality and high-performing/low-performing organisations (using results of annual national staff and patient surveys). A total of 423 surveys were completed by patients (26% response rate).

Results

A different internal structure to the PEECH instrument emerged in English hospitals. However, both the existing and new factor models were similar in terms of fit. The correlations between the new PEECH factors and the PPE-15 were all in the expected direction, but two of the new factors (personal interactions and feeling valued) were more strongly associated with the PPE-15 than the remaining two factors (feeling informed and treated as an individual).

Conclusions

PEECH can help to build an understanding of complex interpersonal aspects of quality of care, alongside the more transactional and functional aspects typically captured by PPE-15. Further testing of the combined instrument should be undertaken in a wider range of healthcare settings.

Keywords: Patient-centred care, surveys, Patient satisfaction, Quality improvement, Audit and feedback

Article summary.

Article focus

To examine how one instrument—‘The Patient Evaluation of Emotional Care during Hospitalisation’ (PEECH)—may strengthen understandings of the relational aspects of patient experience in English hospitals.

To test the internal structure of PEECH using factor analysis and compare it with the more commonly used Picker framework of patient experience which focuses largely on the functional and transactional aspects of patient experience.

Key messages

A different internal structure to the PEECH instrument emerged in English hospitals than that found in Australia where the tool was originally developed.

The correlations between the new PEECH factors and the Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire (PPE)-15 were all in the expected direction, but two of the new factors (personal interactions and feeling valued) were more strongly associated with the PPE-15 than the remaining two factors (feeling informed and treated as an individual).

Healthcare organisations that are seeking to gain more detailed insights into the relational aspects of patients’ experiences of care can deploy PEECH alongside the PPE-15 instrument.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first time that the PEECH instrument has been tested in English hospitals, and the number of respondents is the largest yet reported anywhere.

This is the first time that the results of PEECH have been compared to the PPE-15, providing evidence to underpin a more strategic approach to the active measurement and reporting of different aspects of patient experiences (relational, functional and transactional).

PEECH was designed for acute settings; the emphasis placed on security, knowing, personal value and connection may differ in community healthcare settings and new constructs could be required.

The overall response rate was 26%; we were unable to send reminders to non-responders.

Introduction

How patients are cared for and looked after is centrally important to any assessment of the quality and performance of healthcare systems and organisations throughout the world. Understanding patient experiences is fundamental to delivering patient-centred care,1 2 which has been described as ‘care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions’.3

It is, therefore, now common for the quality of healthcare not only to be judged on clinical outcomes but also from the perspectives of patients in receipt of care.4 The improvement journeys of leading healthcare organisations in Europe and the USA are characterised by investment in systems for understanding and utilising patient experiences.5 Organisations that have succeeded in fostering patient-centred care have gone beyond quality improvement based solely on clinical measurement and audit and have adopted a broader strategic approach that includes active measurement and feedback reporting of patient experiences.6

While complexities in conceptualising and defining ‘experience’—and differences in the preferences and subjective experiences of individual patients7—have led to ambiguity about understanding of the term and how it can be usefully measured,8 patient experience is commonly considered to be shaped by the behaviours and actions of healthcare staff including showing compassion,9 empathy and responsiveness to a patient's needs, values and preferences.4 It is also seen to relate to aspects of patient's physical needs and comfort, as well as emotional support, such as relieving fear and anxiety.3 A further aspect is ‘seeing the patient as an individual person’10 and involving them and their families or carers in decisions about their own treatment or care.3 A patient's experience has also been linked to organisational factors, including service co-ordination and integration of care.11

A good patient experience is therefore multidimensional12 concerning, first, ‘functional’ aspects of care (such as arranging the transfer of patients to other services, administering medication and helping patients to manage and control pain), ‘transactional’ aspects of care (in which the individual is cared ‘for’, eg, meeting the preferences of the patient as far as timings and locations of appointments are concerned) and ‘relational’ aspects of care (where the individual is cared ‘about’, eg, care is approached as part of an ongoing relationship with the patient13).

However, most survey-based approaches to measure patient experiences focus largely on functional or transactional aspects of care8 and are therefore limited because they do not provide specific information to healthcare providers about the relational aspects of care, which are known to be important to patients.14 The aim of this paper was to examine how one instrument—The Patient Evaluation of Emotional Care during Hospitalisation (PEECH)15 16—may strengthen understandings of the relational aspects of patient experience in English hospitals. PEECH was developed in Australia to measure a patient's experiences of emotional care. In this paper, we test the internal structure of PEECH using factor analysis and compare it with the more commonly used Picker framework17 of patient experience (Short-Form & Overall Impression items), which focuses largely on the functional and transactional aspects of patient experience.

Background

A number of patient-centred healthcare models have been developed which set out core components of ‘patient experience’.17a Arguably the most widely known framework is the Institute of Medicine (IOM) six core dimensions of patient-centred healthcare3: compassion, empathy and responsiveness to needs, values and expressed preferences; coordination and integration; information, communication and education; physical comfort; emotional support, relieving fear and anxiety and involvement of family and friends. A wide range of quality measures can be used to examine these components of patient experience, including Patient Reported Experience Measures and Patient Reported Outcome Measures.17b

More familiar to the European context is the Picker framework,17 which was the basis for the original, annual, national patient surveys in acute hospitals in England, introduced in 2001. In addition to the IOM dimensions, the Picker framework includes ‘access’ as one of the eight dimensions and explicitly identifies ‘continuity of care’ as a separate dimension (the IOM includes this aspect within a broader dimension of ‘coordination and integration of care’). The Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire (known as the PPE-15) is a 15-item ‘Short-Form’ version of the Picker Adult In-Patient Questionnaire, designed for use in inpatient care settings developed by the Picker Institute to identify patient experiences and problems with specific healthcare processes that affect the quality of care. It contains specific questions about whether certain processes and events occurred during the patient's care episode. Each question has either three or four possible responses (eg, Yes, always, Yes, sometimes, No, and Not relevant). Responses are summed to produce a score (0 to 15). The questions can be incorporated into other inpatient surveys as part of routine data collection, allowing the comparison of scores over time.

Both the IOM and Picker frameworks are informed by the same original research1 and are technically sound, useful and widely recognised. However, the overall picture in England is one of National Health Service (NHS) acute hospitals becoming less dependent on standardised patient surveys and seeking to gain more detailed insights into specific aspects of patients’ experiences of care. Healthcare organisations are increasingly deploying a wider range of other methods and approaches locally to measure patient experiences8 which reflect a wider trend of making greater use of patient experience data generated to inform service development and quality improvement.18

The PEECH instrument, developed by Williams and Kristjanson in 2008, is different from survey instruments currently employed in England. Their qualitative research in Australia identified characteristics of interpersonal interactions that hospitalised patients perceived to be therapeutic and used these to generate an emotional care construct with three subscales—level of security (10 items), level of knowing (three items) and level of personal value (10 items).19 High ratings on these items are then used to indicate whether patients feel secure, informed and valued. The instrument was further developed and tested in a private Australian hospital on 132 patient respondents from 10 different hospital settings.

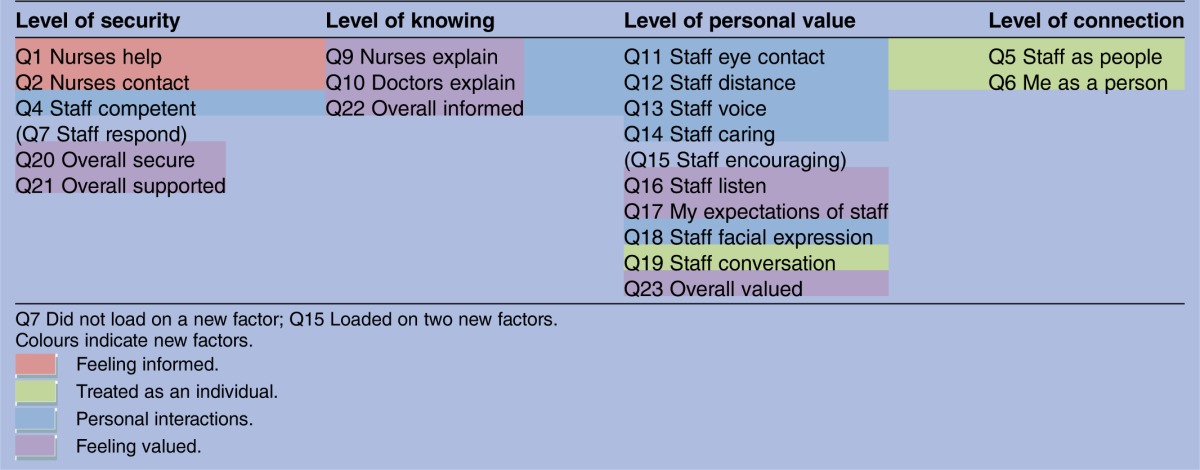

Table 1, using shortened labels for each item, shows the factors and their internal structure that were identified by Williams and Kristjanson using exploratory factor analysis (EFA).15 A fourth factor emerged which they named ‘Level of connection’. The subsequent PEECH instrument asks patients to think about all the staff they have had contact with during their current admission (19 questions); to think about how they felt during their stay in hospital (4 questions) and about personal characteristics (13 questions).15 Responses to the first two sets of questions are recorded on a four-point scale (0–3; none, some staff, most staff and all staff). A subsequent study, in an acute-care Australian public hospital, to further explore the psychometric properties of PEECH and to identify any differences between ward and hospital environments, found an identical factor/internal structure.16

Table 1.

Patient Evaluation of Emotional Care during Hospitalisation factors

| Level of security | Level of knowing | Level of personal value | Level of connection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 Nurses help | Q9 Nurses explain | Q11 Staff eye contact | Q3 Doctor contact |

| Q2 Nurses contact | Q10 Doctors explain | Q12 Staff distance | Q5 Staff as people |

| Q4 Staff competent | Q22 Overall informed | Q13 Staff voice | Q6 Me as a person |

| Q7 Staff respond | Q14 Staff caring | Q8 Staff 24 h | |

| Q20 Overall secure | Q15 Staff encouraging | ||

| Q21 Overall supported | Q16 Staff listen | ||

| Q17 Staff expectations | |||

| Q18 Staff facial expression | |||

| Q19 Staff conversation | |||

| Q23 Overall valued |

For details of full item wording of items used in this study, see appendix 1.

Study context

Our context for testing PEECH in the NHS in England was a larger, 3-year study of the links between staff well-being and patient experience in eight different care settings (four acute and four community).20 The study used staff and patient surveys and in-depth ethnographic research to examine both the nature of staff well-being and its relationship with patient experience. Specifically, the study aimed to identify which organisational strategies and practices are likely to have the most impact on staff well-being and patients’ experiences of healthcare. The final report of the study provides full details of the methods and settings where the instrument was tested.20 In this paper we report, first, on our work to validate the PEECH instrument in the four acute settings and, second, compare the results with those from the PPE-15 which was fielded in the same questionnaire survey.

Aim

To ascertain whether PEECH is a valid and robust measure for use in acute English healthcare settings using secondary data from a study of well-being and patient experience by:

Validating the internal structure of PEECH and

Comparing PEECH with the Picker Short Form (PPE-15), an established measure of functional and transactional patient experience.

Methods

Questionnaire

For the purposes of our study, we developed a 48-item questionnaire which used the PEECH instrument to capture the relational aspects of care and the Picker Short-Form to capture functional and transactional aspects of care.15 17 All participants were given the same questionnaire with the Picker Short-Form always following PEECH. We adapted the PEECH instrument with some small adjustments in wording. Two items were excluded: Q3 ‘doctor contact’ and Q8 ‘staff 24 hours’ because of their failure previously to load strongly on a single factor (<0.4) and because patients in our study were sent the survey postdischarge.

Sample

We tested the new instrument in four acute service settings that were considered to be contrasting in terms of organisational performance and profile. Selection of the acute service settings was based on achieving variation of the following factors: teaching hospital/district general hospital, urban/rural locality and high-performing/low-performing organisations (using results of annual national staff and patient surveys). Each of these four settings was categorised into (1) high-performing or low-performing hospital and (2) high-performing or low-performing service. The numbers surveyed and the responses rates are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Microsystem categories and survey information

| Performance |

Patient survey |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical microsystem | Trust | Microsystem | Surveyed | Responders | Response rate (%) |

| Emergency Admissions Unit | Low | Low | 690 | 159 | 23 |

| Maternity | Low | High | 580 | 137 | 24 |

| Medicine for the Elderly | High | Low | 111 | 26 | 23 |

| Haemato-oncology | High | High | 245 | 101 | 41 |

| All | 1626 | 423 | 26 | ||

Most participants (86% n=362) provided answers to all 21 PEECH items and almost all provided answers to at least half of the items (99% answered 11 or more items). Detailed information on the patient sample is provided in the full study report.20 Haematology was the only service setting where the proportion of male respondents was higher than that of females. Apart from Maternity, the highest proportion of women was found among patients admitted to the emergency admissions unit.

Factor analysis

A factor analytic approach was used to compare the factor structures of the two instruments. EFA was undertaken using Mplus (V.4.2), which has procedures for the factor analysing short ordinal scales.21 Mplus produces factor loadings for both Promax and Varimax rotation. The former was preferred because there was an expectation that the factors would be correlated. EFA was conducted using the missing at random (MAR) method. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was analysed using complete cases only and MAR method. The parameter estimates for both approaches were very similar. The complete case CFA in Mplus provides more measures of fit than the MAR method, and these have been reported in the results.

Once the factor structure was established using EFA, CFA was undertaken. The factor structure of the Williams and Kristjanson model was compared with the structure arising from the EFA using a number of established fit indices that included the model χ2, Cumulative Fit Index (CFI; range 0–1), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI; range 0–1), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; good fit <0.05; adequate fit <0.08), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMSR), Weighted Root Mean Square Residual and Cronbach's α. Note that in the EFA only the model χ2, RMSEA and Root Mean Square Residual (RMSR) were available in the version of Mplus that we used.

To examine the external validity of the instrument, factor mean scores were compared across four acute services, and at the patient level, factor scores were correlated with the PPE-15 index score.

Results

Item means were in the range 1.59–2.60, and most (18/21) were 2.1 or above, except for Q5 staff as people (1.65), Q6 me as a person (1.59) and Q19 staff conversation (1.74). A summary of the measures of fit produced by the EFA procedure is shown in table 3. The scree plot of the eigenvalues suggested that at least two factors were necessary for a valid measure. The first three factors all had eigenvalues of over 1. The fit indices suggested that at least four factors were required. The five factor model was not noticeably superior to the four factor model based on the fit indices, and therefore the latter was preferred on grounds of parsimony.

Table 3.

Measures of fit

| Number of factors | RMSEA | RMSR | χ2/d.f. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.171 | 0.087 | 13.43 |

| 2 | 0.118 | 0.054 | 6.88 |

| 3 | 0.093 | 0.040 | 4.63 |

| 4 | 0.069 | 0.028 | 3.04 |

| 5 | 0.055 | 0.021 | 2.27 |

d.f., degrees of freedom; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; RMSR, Root Mean Square Residual.

Table 4 shows the items with loadings ≥0.4 that loaded under each factor. One item did not load strongly on any factor (Q7 ‘staff respond’), and one loaded strongly on two (Q15 ‘staff encouraging’). We have used the items that loaded on each factor to determine a provisional factor name. The first was named ‘Feeling informed’, the second ‘Treated as an individual’, the third ‘Personal interactions’ and the fourth ‘Feeling valued’. The correlations between these factors ranged from 0.51(feeling informed/treated as an individual, feeling informed/personal interactions) to 0.72 (personal interactions/feeling valued).

Table 4.

Factor structure and item loadings ≥0.4

| Feeling informed | Treated as an individual | Personal interactions | Feeling valued | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 Nurses help | 0.69 | |||

| Q2 Nurses contact | 0.77 | |||

| Q4 Staff competent | 0.50 | |||

| Q5 Staff as people | 0.88 | |||

| Q6 Me as a person | 0.92 | |||

| Q7 Staff respond | ||||

| Q9 Nurses explain | 0.57 | |||

| Q10 Doctors explain | 0.72 | |||

| Q11 Staff eye contact | 0.75 | |||

| Q12 Staff distance | 0.84 | |||

| Q13 Staff voice | 0.96 | |||

| Q14 Staff caring | 0.59 | |||

| Q15 Staff encouraging | 0.45 | 0.47 | ||

| Q16 Staff listen | 0.43 | |||

| Q17 Staff expectations | 0.48 | |||

| Q18 Staff facial expression | 0.69 | |||

| Q19 Staff conversation | 0.50 | |||

| Q20 Overall secure | 0.85 | |||

| Q21 Overall supported | 0.81 | |||

| Q22 Overall informed | 0.92 | |||

| Q23 Overall valued | 0.71 |

The degree of divergence between the existing and emergent internal structures is illustrated in table 5. The table shows how the internal structures from PEECH (level of security, level of knowing, level of personal value and level of connection) compare with the internal structures identified by our study (feeling informed, treated as an individual, personal interactions and feeling valued). The PEECH factors are shown in columns and the new factors are indicated by different coloured boxes. The point to note is that the ordering of items differs and there has been some movement of items between factors.

Table 5.

Comparison of factors and internal structures

The next step was to see how well the factor structure in table 4 and the PEECH instrument fitted the well-being study data.20 Both the existing and new factor structures were similar in terms of fit (CFI 0.93 vs 0.95, TLI 0.99 vs 0.99, RMSEA 0.13 vs 0.11; SRMSR 0.06 vs 0.05, WRMSR 1.66 vs 1.40, Cronbach's α 0.82–0.94 vs 0.77–0.94), while noting that these fit indices could be biased upwards in favour of the new structure because the EFA and CFA were both applied to the same data. None of the items has either very high or low scores and the propensity of such items to load on the same factor was not an issue.22 The scores generated for each factor clearly distinguish between the four acute service settings in the way that we would expect. There is more variability between high-performing and low-performing services within hospitals than between high-performing and low-performing hospitals (table 6).

Table 6.

Factor mean scores by hospital and microsystem

| High–low performing trust/microsystem | Feeling informed | Treated as an individual | Personal interactions | Feeling valued |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low–low | ||||

| Mean | 1.93 | 1.30 | 2.34 | 2.13 |

| SD | 0.88 | 0.94 | 0.66 | 0.78 |

| N | 155 | 149 | 156 | 158 |

| Low–high | ||||

| Mean | 2.55 | 1.75 | 2.53 | 2.42 |

| SD | 0.56 | 0.87 | 0.48 | 0.61 |

| N | 139 | 137 | 139 | 139 |

| High–low | ||||

| Mean | 1.98 | 1.53 | 2.21 | 2.33 |

| SD | 0.89 | 1.02 | 0.85 | 0.76 |

| N | 24 | 25 | 25 | 24 |

| High–high | ||||

| Mean | 2.24 | 2.10 | 2.66 | 2.64 |

| SD | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.45 | 0.53 |

| N | 100 | 99 | 101 | 99 |

| All | ||||

| Mean | 2.21 | 1.66 | 2.47 | 2.36 |

| SD | 0.81 | 0.93 | 0.59 | 0.70 |

| N | 418 | 410 | 421 | 420 |

The correlations between the four factors and the Picker Short-Form index were all in the expected direction; the better the performance based on factor scores, the fewer the problems detected by the Picker instrument. These correlations ranged from −0.43 (Feeling Informed) to −0.77 (Feeling Valued). A similar picture emerged for individual Picker items that focused on the patient's overall impression of their experience.

Discussion

There were notable differences between the internal structures of the PEECH instrument developed in Australia and the one arising from this study. We identified four new factors: feeling informed, treated as an individual, personal interactions and feeling valued. These factors had varying degrees of overlap with those from the two Australian studies.15 16 This could be due to a number of reasons; first, there could be a genuine difference in the relational aspects of patient care found in Australia and the UK. Alternatively, the differences could be down to study methodology and the sample. The Australian private and public hospital samples were smaller (n=132 and 251, respectively, vs 423) but covered a far wider range of specialities than in this study (10, 13 vs 4).15 16 20 Patients responding to the two Australian studies were all located in hospital at the time of the survey, whereas here the questionnaires were distributed postdischarge; therefore, differences could be due to recall.

The ‘Personal interactions’ and ‘Feeling valued’ factors were more strongly associated with the PPE-15 than the ‘Feeling informed’ and ‘Treated as an individual’ factors. Healthcare organisations could, potentially, use this new instrument on its own in the knowledge that the ‘Feeling valued’ factor is measuring something similar to the Picker Short-Form and Picker ‘Overall impression’ items. However, the new factor structure requires testing and confirmation in other UK acute-care settings with different types of patients before we can have absolute confidence in its generalisability and begin developing a theoretical framework.

The instrument was originally designed for acute settings. There is no reason why a comparable instrument should not be developed for community settings drawing on this research. The theoretical underpinning may require adjustment. The emphasis placed on security, knowing, personal value and connection may differ and new constructs could be required.

Relational models of care emphasise the importance of an ongoing relationship with the patient. There is a need generally to develop methods for evaluating patients’ perceptions and experiences of continuity of care and coordination of services. Thus, the potential of the instrument to inform understandings about continuity between different service settings and relationship building with patients is an important issue that requires further research. These are key issues for patients and families, but there is a need to build technical knowledge of the issues and the means to collect and analyse and feed back appropriate patient experience data.

Conclusions

We developed a 48-item questionnaire which used the PEECH instrument to capture patient experiences of relational aspects of care and the PPE-15 to capture patient experiences of functional and transactional aspects of care.15–17 Following an EFA of the instrument within four hospital services in England, a different internal structure to the PEECH instrument developed in Australia emerged.19 The correlations between the factors and the PPE-15 were all in the expected direction. Two of the new factors (personal interactions and feeling valued) were more strongly associated with the PPE-15.

Healthcare organisations that are seeking to gain more detailed insights into the relational aspects of patients’ experiences of care can deploy PEECH alongside the PPE-15 instrument. This could inform a more strategic approach to the active measurement and reporting of different aspects of patient experiences (relational, functional and transactional). PEECH can help to build an understanding of the more complex interpersonal aspects of quality including compassion, empathy and responsiveness to personal needs, alongside transactional and functional aspects of care which are mostly captured by the PPE-15. Further testing of the combined instrument should be undertaken in a wider range of healthcare settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated in this research through completing a survey. They are also grateful to the senior managers and microsystem leaders in the four participating NHS Trusts who facilitated research access.

Appendix 1. PEECH factors and items used in this study

| Factor | Item | Item question | Shortened label |

|---|---|---|---|

| Security | 1 | The nurses told me that they were there to help me | Nurses help |

| Security | 2 | The nurses told me how I could contact them if I needed assistance | Nurses contact |

| Security | 4 | The staff appeared confident and able to perform specific tasks when caring for other patients or me | Staff competent |

| Connection | 5 | I had the opportunity to get to know the staff as people | Staff as people |

| Connection | 6 | The staff used opportunities to get to know me as a person | Me as a person |

| Security | 7 | The staff responded quickly and effectively to requests for assistance | Staff respond |

| Knowing | 9 | The nurses explained with openness and honesty what was happening and what to expect | Nurses explain |

| Knowing | 10 | The doctors (or doctor) explained with openness and honesty what was happening and what to expect | Doctors explain |

| Personal value | 11 | The staff used appropriate eye contact when communicating with me | Staff eye contact |

| Personal value | 12 | The staff were neither too close nor too far away when they communicated with me | Staff distance |

| Personal value | 13 | The staff used an appropriate tone of voice when they communicated with me | Staff voice |

| Personal value | 14 | The staff displayed gentleness and concern when they cared for me | Staff caring |

| Personal value | 15 | The staff encouraged me when I needed support | Staff encouraging |

| Personal value | 16 | I felt that the staff really listened to me when I talked | Staff listen |

| Personal value | 17 | The care that I have received from the staff has exceeded my expectations | Staff expectations |

| Personal value | 18 | The staff used appropriate facial expressions when communicating with me | Staff facial expression |

| Personal value | 19 | The staff engaged me in social topics of conversation at suitable times and I felt safe during this admission | Staff conversation |

| Security | 20 | I felt safe during this admission | Overall secure |

| Security | 21 | I had the contact and support from the staff that I have needed | Overall supported |

| Knowing | 22 | I felt informed during this admission. I knew what was happening, what I needed to do and what to expect | Overall informed |

| Personal value | 23 | I felt valued as a person during this admission | Overall valued |

Footnotes

Contributors: JM was the Principal Investigator for the larger NIHR-funded study, of which the survey was one component, and EM was on the project advisory group. TM, GR, JM and MA designed the survey. GR, JM and MA recruited respondents and fielded the survey in the case study sites. TM analysed the survey results. EM and TM drafted the paper, and GR, JM and MA provided comments and suggestions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The study that informs this paper was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme (project number SDO/213/2008). The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR SDO programme or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: A favourable ethical opinion for this research was granted by the North West London Research Ethics Committee (North London REC 3) in October 2009, REC reference: 09/H0709/51. Local Research & Development approval was granted by the participating NHS organisations.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The survey was part of a larger study into the links between staff well-being and patient experience (see ‘Funding’ statement). The 3-year study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research (NIHR HS&DR) Programme, which was led by the National Nursing Research Unit, and involved academics and practitioners from the Department of Management at King's College London and the University of Southampton, involved over 200 h of direct care observation, patient focus groups, interviews and surveys, as well as interviews with 55 senior managers and staff surveys at four different trusts. The full report with all the findings has now been published online at: http://www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/SDO_FR_08-1819-213_V01.pdf (accessed November 2012). Further details are available from the Principal Investigator, Professor Jill Maben (jill.maben@kcl.ac.uk).

References

- 1.Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J, et al. Through the patient's eyes: understanding and promoting patient-centered care. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frampton S, Charmel P, eds. Putting patients first: best practices in patient-centered care. 2nd edn San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coulter A, Fitzpatrick R, Cornwell J. The point of care. Measures of patients’ experience in hospital: purpose, methods and uses. London: The King's Fund, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bate P, Mendel P, Robert G. Organizing for quality: the improvement journeys of leading hospitals in Europe and the United States. Abingdon: Radcliffe, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luxford K, Gelb SD, Delbanco T. Promoting patient-centered care: a qualitative study of facilitators and barriers in healthcare organizations with a reputation for improving the patient experience. Int J Qual Health Care 2011;23:510–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaller D. Patient centred care: what does it take? Oxford: Picker Institute and The Commonwealth Fund, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robert G, Cornwell J.2011.. What matters to patients? Policy recommendations. A report for the Department of Health and NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. NHS Institute for Innovation & Improvement; Warwick. http://www.institute.nhs.uk/images/Patient_Experience/Final%20Policy%20Report%20pdf%20doc%20january%202012.pdf. (accessed Sep 2012)

- 9.Firth-Cozens J, Cornwell J. The point of care: enabling compassionate care in acute hospital settings. London: The King's Fund, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodrich J, Cornwell J. Seeing the person in the patient. London: The King's Fund, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leatherman S, Sutherland K. Patient and public experience in the NHS. London: The Health Foundation, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornwell J, Foote C. Improving patients’ experiences. An analysis of the evidence to inform future policy development. London: The King's Fund, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iles V.2011. Why Reforming the NHS Doesn't Work. The importance of understanding how good people offer bad care. http://www.reallylearning.com/Free_Resources/MakingStrategyWork/reforming.pdf. (accessed Oct 2012)

- 14.Robert G, Cornwall J, Brearley S, et al. What matters to patients; developing the evidence base for measuring and improving the patient experience. A report for the Department of Health and NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. Warwick: NHS Institute for Innovation & Improvement, 2011.. http://www.institute.nhs.uk/images/Patient_Experience/Final%20Project%20Report%20pdf%20doc%20january%202012.pdf. (accessed Sep 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams A, Kristjanson L. Emotional care experienced by hospitalised patients: development and testing of a measurement instrument. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:1069–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams AM, Pienaar C, Toye C, et al. Further psychometric testing of an instrument to measure emotional care in hospital. J Clin Nurs 2011;20:3472–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S. The Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire: development and validation using data from in-patient surveys in five countries. Int J Qual Health Care 2002;14:353–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17a.Groene O. Patient centredness and quality improvement efforts in hospitals: rationale, measurement, implementation. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2011;23:531–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17b.Reay N. How to measure patient experience and outcomes to demonstrate quality in care. Nursing Times 2010;106:12–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curry R. Vision to reality: using patients’ voices to develop and improve services. Br J Community Nurs 2006;11:438–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams A, Dawson S, Kristjanson L. Translating theory into practice: using action research to introduce a coordinated approach to emotional care. Patient Educ Couns 2008;73:82–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maben J, Peccei R, Adams M, et al. Patients’ experiences of care and the influence of staff motivation, affect and wellbeingl. Final report. Southampton: NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation Programme, 2012. http://www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/SDO_FR_08–1819-213_V01.pdf. (accessed Nov 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muthen LK, Muthen B. Mplus user's guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorsuch RL. Factor analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1983 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.