Abstract

Introduction

Non-dystrophic Myotonia (NDM) is characterized by myotonia without muscle wasting. A standardized quantitative myotonia assessment (QMA) is important for clinical trials.

Methods

Myotonia was assessed in 91 individuals enrolled in a natural history study using a commercially available computerized handgrip myometer and automated software. Average peak force and 90% to 5% relaxation times were compared to historical normal controls studied with identical methods.

Results

30 subjects had chloride channel mutations, 31 sodium channel mutations, 6 DM2, and 24 no identified mutation. Chloride channel mutations were associated with prolonged 1st handgrip relaxation times, and warm up on subsequent handgrips. Sodium channel mutations were associated with prolonged 1st handgrip relaxation times and paradoxical myotonia or warm-up, depending on underlying mutations. DM2 subjects had normal relaxation times but decreased peak force. Sample size estimates are provided for clinical trial planning.

Conclusion

QMA is an automated, non-invasive technique for evaluating myotonia in NDM.

Search terms: natural history, ion channel mutation, muscle disease, myotonia, non-dystrophic myotonia

Introduction

Non-dystrophic myotonia (NDM) is caused by mutations in muscle sodium and chloride channels1–5. The key feature of NDM is myotonia, which is delayed muscle relaxation following contraction. Clinically, patients experience stiffness, pain and weakness. In addition, transient paresis has been described, where temporary weakness resolves with repeated muscle contractions6–9. Myotonia can be evoked either by voluntary contraction or percussion of muscles and by electrical stimulation. Classically, NDM can be divided into two major disease categories: myotonia congenita (MC) associated with chloride channel mutations, and paramyotonia congenita (PMC) associated with sodium mutations. MC patients have a pattern of “warm-up” on repeated muscle contractions, whereas PMC patients have a pattern of worsening of symptoms, or paradoxical myotonia (paramyotonia), with repeated contractions. Other sodium channel disorders associated with NDM are hyperkalemic periodic paralysis and potassium aggravated myotonia2,10,11. In addition myotonic dystrophy type 2 (DM2) caused by an unstable expansion of a CCTG tetranucleotide repeat may have a similar clinical presentation to NDM 12,13.

Prior studies in NDM have used experimental techniques to quantify handgrip myotonia. A force transducer, or flexion against a metal plate connected to a force transducer have been used to evaluate peak force, 3/4 relaxation time, or 90% to 10% relaxation times. Patients with PMC have cold-induced myotonia which worsens with exercise, and concurrent reduction in peak force 14. Patients with potassium aggravated myotonia have delayed exercise-induced myotonia, which is provoked by potassium, without changes in force 15. More recently, a commercially available quantitative measure of handgrip myotonia (QMA) to calculate peak force and relaxation times following forced handgrips has been used in patients with myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1)16–20. This technique was subsequently used successfully to show a reduction in 90% to 5% relaxation time after treatment with mexiletine in a randomized, placebo-controlled cross-over study in DM1. Although early studies in NDM documented the key patterns of myotonia in NDM, to date there are no studies utilizing a commercially available system and standardized protocol in a broad group of NDM patients. The ability to quantify not only relaxation times, but also the patterns of myotonia on sequential handgrips may be useful for documenting response to therapy in future NDM trials.

Methods

Subjects

The NDM subjects enrolled in this study (n=91) were all part of the Consortium for Clinical Investigation of Neurological Channelopathies (CINCH) Group’s Non-dystrophic Myotonia: Genotype-Phenotype Correlation and Longitudinal Study, sponsored by the NIH Office of Rare Diseases Research and NINDS. Subjects were recruited from 6 academic centers across the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom between 2006 and 2009. All sites received approval by their IRB for investigations involving human subjects, and informed consent was obtained from all study participants. For subjects less than 18 years of age, patient assent and parental consent were obtained.

Patients were included: 1) if they were older than 6 years old; 2) had clinical symptoms or signs suggestive of a myotonic disorder; and 3) had myotonic discharges on needle electromyography. For patients with a history of taking medications that can cause myotonia (fibrate acid derivatives, hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA reductase inhibitors, chloroquine, or colchicine), symptoms and signs of myotonia were required to persist after discontinuation. Patients were excluded if they had features suggestive of myotonic dystrophy (ptosis, temporal wasting, mandibular weakness, cataracts before the age of 50, or evidence for multi-system involvement), or other neurological conditions that might affect assessment of study measurements.

Measurements

All subjects underwent a baseline visit which included a symptom questionnaire, physical examination, electrophysiological studies, and blood sample for genetic testing. For this study, subjects were grouped into chloride channel mutations, sodium channel mutations, DM2, and no mutation identified. Sodium channel subjects were further broken down into specific mutations. Chloride channel subjects were subdivided into recessive or dominant mode of inheritance based on number of mutations, copy number, and family history. There were some subjects with novel chloride channel mutations or with mutations that have been associated with both recessive and dominant disease who could not be further classified21.

Quantitative Myotonia Assessment (QMA)

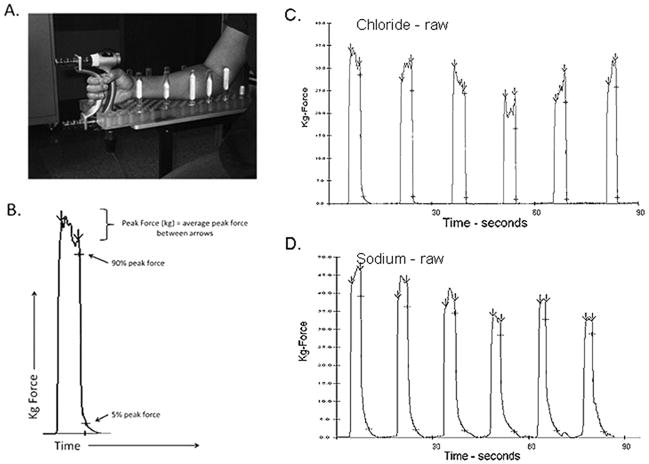

Average peak force and 90% to 5% relaxation times after maximal voluntary isometric contractions (MVIC) were measured. As described previously 16,18, patients were seated upright in a modified chair that permits reproducible adjustment of chair and arm height, with the elbow flexed at approximately 90 degrees and the forearm stabilized on a pegboard with the wrist in neutral position to prevent flexion or extension of the wrist (Figure 1). Three trials were performed consisting of 6 MVICs lasting 3 seconds separated by 10 second rest periods, with 10 minutes rest between trials. Data were collected with the dynamic-fatigue option of the Quantitative Muscle Assessment software version 4.2 (QMA Systems, Inc., Gainesville, GA) and subsequently analyzed using a customized automated computer program (created by A.W. Wiegner PhD, Harvard Medical School). The automated program identified peaks by marking the points on the force curves where the maximum positive and minimum negative slopes occurred. Between these two points the force was averaged over the plateau to yield the average peak force for each contraction. Relaxation times (seconds) were then calculated at 90% and 5% declines in force from the peak force value (Figure 1). We used the 90% to 5% relaxation time, as this is sensitive to changes in relaxation times occurring at any point in the relaxation phase. This relaxation time interval was used successfully in the randomized, controlled, cross-over trial of mexiletine in DM1 17. Clinical evaluators were trained in the procedure during clinical evaluator training meetings and were given a standardized script to read from during testing.

Figure 1.

Quantitative myotonia assessment apparatus and sample trials. A. Patient is seated in a modified chair with forearm secured in neutral position on a pegboard, fingers gripped lightly around force transducer. B. Automated software identifies peak force onset and offset by positive and negative changes in slope, then peak force is averaged between arrows. The software automatically identifies 90% and 5% of average peak force during the relaxation phase. C. Sample trial for subject with chloride channel mutation. D. Sample trial for subject with sodium channel mutation.

Statistical Considerations

Standard statistical methods were used for all descriptive statistics including the calculation of the unbiased estimate for standard error and standard deviation. All such descriptive statistics were based on one value per subject, such as the means and standard deviations of the 90% to 5% relaxation times for each numbered hand grip used the average over trials. For the comparisons made to healthy controls (Tables 2&3), all “normal” descriptive statistics were taken from previously published articles (n=17, mean age 40.9 years, range 21–62, 47% female, Table 1)16,18. The 95% distribution upper/lower bounds were equal to the sample mean plus or minus 1.96 (0.975 quintile of the Z-distribution) times the standard deviation using the published “normal” estimates. Coefficient of variation (COV), equal to the sample standard deviation divided by the mean, was used to compare inter-trial variation to previously reported values for DM1 18. The correlation coefficients for the pair-wise comparison between the 3 trials employed the Spearman method for each hand grip number then taking the average. A mixed linear model with random effects for both Y-intercept and slope across grip number for each trial within each subject was fitted to the 90% to 5% relaxation times as the dependent variable. The likelihood ratio test was computed to determine if there was any systematic fixed effect of trial over the study cohort. Sample size calculations were based on two-period crossover design and Monte Carlo simulation (N=500) studies using a mixed model with 3 random effects: subject, test (for each treatment period) within subject and trial within test. The standard deviations of these effects were either taken directly from the data or were reasonable approximations based on the known estimates; the values used were: 1.08, 0.71, 0.35, and 0.45 for the subject, test within subject, trial within test and the residual, respectively. The significance level for treatment effect was taken from the Wald test associated with the treatment indicator variable and compared to an alpha of 0.05 (1-tail) to estimate the statistical power.

Table 2.

90% to 5% relaxation times (seconds) for different genetic mutations compared to historical normative data.

| Handgrip 1 | Handgrip 6 | Handgrip 1 – Handgrip 6 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | N | Mean (SD) | >Upper No. (%) | Mean (SD) | >Upper No. (%) | Mean (SD) | Min | Max | >Upper No. (%) | <Lower No. (%) |

| Normal * | 17 | 0.37 (0.10) | - | 0.43 (0.27) | - | −0.06 (0.20) | −0.70 | 0.15 | - | - |

| Chloride | 30 | 1.74 (1.95) | 20(67) | 0.79 (0.64) | 9 (30) | 0.95 (1.68) | −0.53 | 6.35 | 13(43) | 1 (3) |

| Recessive † | 10 | 2.08 (2.20) | 7(70) | 0.69 (0.56) | 3 (30) | 1.38 (2.02) | −0.06 | 6.35 | 5 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Dominant ‡ | 11 | 1.50 (2.33) | 5 (45) | 0.65 (0.67) | 2 (18) | 0.85 (1.78) | −0.29 | 5.20 | 3 (27) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown § | 9 | 1.66 (1.15) | 8 (89) | 1.06 (0.65) | 4 (44) | 0.60 (1.14) | −0.53 | 3.34 | 5 (56) | 1 (11) |

| Sodium | 31 | 0.77 (0.80) | 12 (39) | 1.13 (1.59) | 8 (26) | −0.37 (1.15) | −4.07 | 1.41 | 3 (10) | 7 (23) |

| T1313M | 11 | 1.20 (1.10) | 6 (55) | 2.35 (2.20) | 6 (55) | −1.22 (1.52) | −4.07 | 0.06 | 0 (0) | 5 (45) |

| R1448H | 5 | 0.30 (0.08) | 0 (0) | 0.47 (0.24) | 0 (0) | −0.11 (0.27) | −0.52 | 0.12 | 0 (0) | 1 (20) |

| G1306A | 5 | 0.52 (0.23) | 2 (40) | 0.47 (0.32) | 1 (20) | 0.04 (0.36) | −0.53 | 0.43 | 1 (20) | 1 (20) |

| M1592V | 2 | 0.20 (0.09) | 0 (0) | 0.26 (0.12) | 0 (0) | −0.06 (0.03) | −0.08 | −0.04 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other|| | 8 | 0.77 (0.62) | 4 (50) | 0.48 (0.37) | 1 (13) | 0.30 (0.65) | −0.31 | 1.41 | 2 (25) | 0 (0) |

| DM2 | 6 | 0.41 (0.25) | 2 (33) | 0.27 (0.11) | 0 (0) | 0.14 (0.24) | −0.06 | 0.60 | 1 (17) | 0 (0) |

| No Identified Mutation | 24 | 1.11 (1.64) | 9 (38) | 0.74 (0.89) | 3 (13) | 0.38 (1.65) | −1.44 | 7.11 | 5 (21) | 2 (8) |

N=number, SD = standard deviation, Min = minimum, Max = maximum, Upper = the 95% distribution upper bound, Lower = the 95% distribution lower bound.

Normal values were published in Logigian, E. L., C. L. Blood, et al. (2005). “Quantitative analysis of the “warm-up” phenomenon in myotonic dystrophy type 1.” Muscle Nerve 32(1): 35–42.

Recessive chloride channel mutations include: R105C+F167L+E624fs, c. 180+3A>T (+) 2434C>T p. ? (+) Gln812X, c. 180+3A>T (+) 568G>A p.? (+) Gly190Arg, E624fs, G285E, R894X.

Dominant chloride channel mutations include: A313T, G230E, F306L, R894X.

Inheritence unknown chloride channel mutations: R894X, c. 180+3A>T (+) 1283>C p. ? (+) F428S, V236L, G190R, F484L, F413C, I556N, M560T.

Other sodium channel mutations include: S804F, S1434P, L128P, V1293I, V1589M.

Table 3.

Average peak force (kg) values for different mutation types compared to historical normal values.

| Handgrip 1 | %Change Handgrip 1–6 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | N | Mean (SD) | <Upper No. (%) | %Change (SD) | Min | Max | >Upper No. (%) | <Lower No. (%) |

| Normal * | 17 | 42.46 (12.54) | - | −14.00 (8.00) | −1.00 | 29.00 | - | - |

| Chloride | 30 | 28.50 (16.30) | 9 (30) | 6.16 (30.90) | −39.90 | 84.40 | 13 (43) | 1 (3) |

| Recessive † | 10 | 22.70 (15.20) | 5 (50) | 19.50 (32.60) | −14.50 | 72.70 | 6 (60) | 0 (0) |

| Dominant ‡ | 11 | 36.00 (14.90) | 1 (9) | −8.62 (32.60) | −39.90 | 84.40 | 1 (9) | 1 (9) |

| Unknown § | 9 | 25.70 (17.40) | 3 (33) | 9.45 (20.00) | −24.00 | 42.70 | 6 (67) | 0 (0) |

| Sodium | 31 | 26.50 (8.59) | 4 (13) | −10.10 (18.60) | −56.00 | 28.40 | 8 (26) | 4 (13) |

| T1313M | 11 | 27.30 (8.94) | 0 (0) | −17.5 (21.20) | −56.00 | 25.20 | 2 (18) | 4 (36) |

| R1448H | 5 | 25.20 (8.77) | 1 (20) | −7.56 (14.40) | −17.30 | 17.70 | 1 (20) | 0 (0) |

| G1306A | 5 | 24.50 (11.00) | 1 (20) | 9.55 (17.30) | −18.70 | 28.40 | 4 (80) | 0 (0) |

| M1592V | 2 | 26.20 (13.20) | 1 (50) | −1.22 (7.58) | −6.58 | 4.14 | 1 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Other|| | 8 | 27.50 (7.60) | 1 (13) | −16.10 (10.80) | −29.10 | 0.13 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| DM2 | 6 | 19.20 (7.90) | 3 (50) | −1.87 (17.90) | −21.80 | 26.90 | 3 (50) | 0 (0) |

| No Identified Mutation | 24 | 24.30 (12.70) | 8 (33) | −6.32 (12.10) | −34.10 | 10.20 | 9 (38) | 1 (4) |

N=number, SD = standard deviation, Min = minimum, Max = maximum, Upper = the 95% distribution upper bound, Lower = the 95% distribution lower bound.

Normal values were published in Logigian, E. L., C. L. Blood, et al. (2005). “Quantitative analysis of the “warm-up” phenomenon in myotonic dystrophy type 1.” Muscle Nerve 32(1): 35–42.

Recessive chloride channel mutations include: R105C+F167L+E624fs, c. 180+3A>T (+) 2434C>T p. ? (+) Gln812X, c. 180+3A>T (+) 568G>A p.? (+) Gly190Arg, E624fs, G285E, R894X.

Dominant chloride channel mutations include: A313T, G230E, F306L, R894X.

Inheritence unknown chloride channel mutations: R894X, c. 180+3A>T (+) 1283>C p. ? (+) F428S, V236L, G190R, F484L, F413C, I556N, M560T.

Other sodium channel mutations include: S804F, S1434P, L128P, V1293I, V1589M.

Table 1.

Demographics by mutation subtype.

| Demographics | Normal * | Chloride | Sodium | DM2 | No Identified Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 17 | 30 | 31 | 6 | 24 |

| age (mean) | 40.9 | 38.6 | 47.3 | 55 | 46.3 |

| age (range) | 21–62 | 16–65 | 12–79 | 40–73 | 24–72 |

| gender Female (%) | 8(47.1) | 7 (23.3) | 15 (48.4) | 3 (50.0) | 17 (70.8) |

DM2 = myotonic dystrophy type 2.

The normal values are taken from Logigian, E. L., C. L. Blood, et al. (2005). “Quantitative analysis of the “warm-up” phenomenon in myotonic dystrophy type 1.” Muscle Nerve 32(1): 35–42.

Results

Quantitative handgrip myometry was performed on 91 subjects with the following genetic mutations: 30 with chloride mutations; 31 with sodium channel mutations; and 6 with tetraplet repeats consistent with myotonic dystrophy type 2 (DM2). Genetic testing did not identify sodium or chloride channel mutations in 24 subjects who met the inclusion criteria of this study. The mean age and gender characteristics are listed in Table 1. Overall, subjects were comparable between groups and to the previously published normal volunteer population. DM2 subjects were slightly older (mean 55 years). There were more female subjects in the no identified mutation group (70.8%) and fewer in the chloride channel mutation group (23.3%).

The same day intertrial variation for the first handgrip 90% to 5% relaxation time and average peak force for trials 1–3 was calculated by examining the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean (coefficient of variation, COV) as previously reported in DM1 18. For peak force the mean COV was 17.7% for the total population (18.5% chloride, 19.2% sodium, 15.2% DM2, and 15.7% no identified mutation). COV for 90% to 5% relaxation time was greater than peak force for all groups, with 40.4% for the total population (36.7% chloride, 38.4% sodium, 38.0% DM2, and 48.2% for no identified mutation). With 10 minutes rest between trials there appeared to be no systematic trend towards warm up or paradoxical myotonia between trials. Chloride channel mutation subjects showed mean 90% to 5% relaxation times for the 1st handgrip of 1.58 seconds (± 2.1 SD) for trial 1, 1.86 (± 2.4 SD) for trial 2, and 1.58 (±−1.5 SD) for trial 3. Sodium channel mutation subjects showed 1st handgrip relaxation times of 0.80 seconds (± 0.97 SD) for trial 1, 0.70 (± 0.70 SD) for trial 2, and 0.83 (± 1.1 SD) for trial 3. In addition, the trials were strongly correlated for relaxation times, for trial 1 vs 2 ρ=0.634 (range: 0.517 – 0.676), for trial 2 vs 3 ρ=0.639 (range: 0.557 – 0.818), and for trial 1 vs 3 ρ=0.560 (range: 0.508 – 0.611). However we cannot rule out a more complicated interaction between trial number, underlying mutation, and effects on consecutive handgrips.

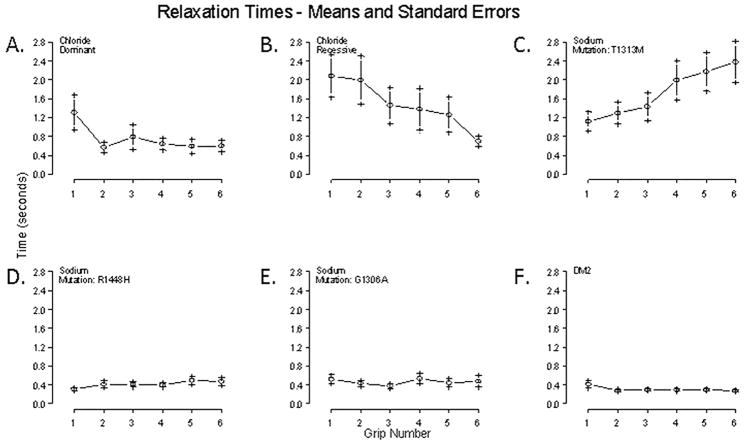

Overall, subjects with NDM had prolonged 1st handgrip 90% to 5% relaxation times compared to normal volunteers (Table 2). 67% of chloride channel subjects had relaxation times greater than the 95% distribution upper bound. The predominant trend was warm up of myotonia in successive handgrips. Overall, subjects with recessive inheritance had increased myotonia compared to dominant (Figure 2). Sodium channel subjects also had prolonged first handgrip relaxation times, but in addition they also showed prolonged 6th handgrip relaxation times compared to normal (1.13 seconds, ±1.49 standard deviation, SD). The pattern of myotonia in successive handgrips was mixed, with 10% showing warm up and 23% showing paradoxical myotonia beyond the 95% distribution upper and lower bounds. Paradoxical myotonia was almost entirely due to T1313M mutation subjects, with 55% showing a 6th handgrip relaxation time greater than the normal 95% confidence interval upper bound, and an increase in myotonia in successive handgrips of 1.22 seconds (±1.52 SD, Figure 2). Interestingly, subjects with R1448H mutations had essentially normal values on QMA. G1306A subjects had a mixed picture; 1 subject had warm up of myotonia in successive handgrips, and 1 subject had paradoxical worsening of myotonia. Two additional sodium channel subjects showed warm-up of myotonia greater than 1 second from handgrips 1 to 6 (one with V1589M, and the other with S1434P mutations). Subjects with DM2 had normal 90% to 5% relaxation times on the QMA.

Figure 2.

90% to 5% relaxation times over sequential handgrips 1–6 for different mutation types. A. Subjects with dominant chloride channel mutations (n=11) show an increased 1st handgrip relaxation times with a pattern of warm-up of myotonia in subsequent handgrips. B. Recessive chloride channel subjects (n=10) show increased relaxations times compared to dominant, there is a pattern of warm-up in successive handgrips. C. Sodium subjects with the T1313M mutation (n=11) show paradoxical myotonia in successive handgrips. D. Subjects with R1448H mutations (n=5), on the other hand have essentially normal QMA relaxation times. E. No clear myotonia was demonstrated in subjects with G1306A mutations (n=5). F. Although there were no clear abnormalities on QMA for DM2 (n=6), in the group there is a subtle trend towards warm-up.

Subjects with no identified mutations had a mixed picture overall, with 38% showing prolonged relaxation times greater than the 95% distribution upper bound. The dominant trend was for warm up (in 21% of subjects), but 2 subjects (8%) showed paradoxical effects.

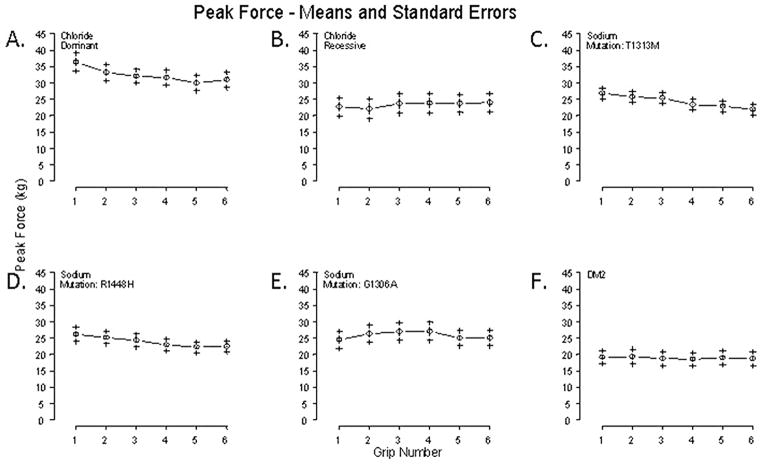

As a group, subjects with NDM showed reduced peak force when compared to a normal population (Table 3). This was most notable in subjects with DM2 (19.20 kg, ±12.5 SD). Chloride channel subjects with recessive inheritance showed decreased 1st handgrip peak force compared to dominant subjects (22.70 kg vs. 36.00 kg respectively), and they had a marked increase in force in successive handgrips (increase of 19.50% compared to decrease of 8.62% for dominant, Figure 3). Overall, subjects with sodium channel mutations showed a drop in force in subsequent handgrips. This was most evident in patients with T1313M mutations, where 36% showed a drop in force greater than the normal 95% distribution lower bound (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Average peak force (kg) over sequential handgrips 1 to 6 for different mutation types. A. Dominant chloride channel subjects (n=11) have increased 1st handgrip peak force compared to recessive subjects which decreases in subsequent handgrips. B. Recessive chloride channel subjects (n=10) show an increase in force in successive handgrips. C. Sodium channel subjects with the T1313M mutation (n=11) show the largest drop in force over subsequent handgrips compared to D. R1448H subjects (n=5). E. G1306A subjects (n=5) show an increase in force in subsequent handgrips. F. DM2 subjects (n=6) show an essentially flat peak force versus handgrip profile.

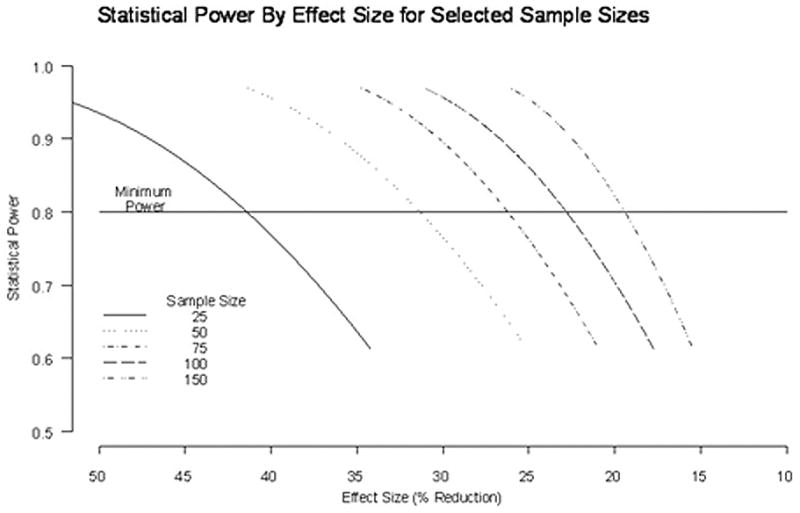

In planning clinical trials due to the rarity of the individual mutation types, it may be more practicable to power studies using 90% to 5% handgrip relaxation time estimates based on the total NDM population. In figure 4 we show a graph relating study power to effect size for different sample sizes. Due to the rarity of NDM and the chronic nature of symptoms a cross-over design is likely to be more practicable than a parallel design. For example, 50 subjects would have 80% power to detect a reduction in average 90% to 5% relaxation time of just over 30% between treatment and placebo, with a level of significance of 0.05.

Figure 4.

Power curve versus effect size for cross-over trial. 50 subjects would have 80% power to detect a reduction in 90% to 5% relaxation time of just over 30% with a level of significance of 0.05. Y axis = statistical power. X axis = percent reduction in 90% to 5% relaxation time. Alpha = 0.05.

Discussion

Where prior studies have demonstrated the utility of using this commercial system for measuring handgrip myotonia in patients with DM1 16,19,18, here we examined the utility of this technique in NDM, a population comprised of both skeletal muscle sodium and chloride channel mutations 1–5,22. In addition, we included a subgroup of DM2 subjects who presented with myotonia in the absence of other systemic features characteristic for myotonic dystrophies, similar to NDM 12,13.

Intertrial variability in this population was greater than in normal individuals, but it was similar to previously published reports using the QMA in DM1, likely reflecting the natural variability in myotonia. The coefficient of variation for peak force and 90% to 5% relaxation time were 17.7% and 40.4% respectively (versus 10.7% and 33.2% for DM1, and 5.4% and 23.1% for normal individuals)18. The COV was lower for subjects with identified mutations.

In prior reports, DM1 showed a relatively constant level of force in repetitive handgrips (a drop of 6%) compared to normal individuals (a drop of 14%), and a large decrease in 90% to 5% relaxation times consistent with the phenomenon of warm-up 16. In NDM, overall trends in sequential peak force and 90% to 5% relaxation times were characteristic for genetic mutations. Overall, the groups showed prolongation of 1st handgrip relaxation times compared to normal. Chloride channel patients showed a pattern of warm-up in subsequent handgrips, which corresponded with an increase in peak force. The changes in peak force were largely driven by subjects with recessive inheritance who showed a phenomenon which may be consistent with prior reports of transient paresis23,9,24,7. Unfortunately, this protocol was not designed to document the absolute drop in peak force over a single handgrip. However subjects with recessive chloride channel mutations had an average decrease in 1st handgrip peak force compared to dominant subjects, which warmed-up over subsequent handgrips. Another possibility is that subjects with recessive chloride channel mutations were simply weaker than dominant subjects and demonstrated more myotonia. It is not possible to distinguish between myotonia and transient paresis using this protocol, as the two effects are not independent of each other.

Patients with sodium channel mutations also showed an increase in 1st handgrip relaxation times. However paradoxical myotonia using this protocol was only seen consistently in patients with T1313M mutations. This protocol, although it combines repeated contractions separated by 10 minutes rest, was not sufficient to provoke the prominent delayed myotonia previously described in myotonia fluctuans 15. One alternative to the QMA system might be to use repetitive short exercise testing 25,26. This test is currently used for diagnostic purposes. Patients with chloride channel mutations show a characteristic decrement in the compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitude immediately post exercise, which warms up on repetition of the test. Patients with PMC show a delayed decrement in CMAP after short exercise, which is exacerbated by cold. Although useful to help guide genetic testing it is unclear how a common single outcome for both chloride and sodium channel patients could be designed. The short exercise test uses immediate repetition of the test to facilitate responses along with cooling of the limb. The useful patterns of changes in CMAP amplitude occur at different time points, are either facilitated or diminished by repetition, and often require cooling to increase sensitivity of results. And patients with mutations associated with potassium aggravated myotonia tend to have normal testing. Indeed the advantage of the current QMA standardized protocol and automated analysis package is its ability to be used by multiple sites in multiple countries in a clinical trial setting. For NDM in particular, where the rarity of the disorder necessitates combining groups which have often been described separately to increase power, what is lost in diagnostic sensitivity is gained in a simpler protocol and automated analysis.

Recently the QMA was used as an outcome measure to show significant changes in relaxation times before and after treatment with mexiletine, an antimyotonic agent in DM117. It may be that for smaller trials, or n of 1 trials where the goal in to establish utility of a therapy in a single patient or a small group of patients, the protocol could be maximized to increase its sensitivity. Either fitting relaxation time curves with a regression model to estimate relaxation times27 and reduce variability, or using repetitive stimulation to evoke myotonia 28 may prove useful in future trials. Additional strategies to help quantify transient paresis by measuring the drop in force over a single handgrip may prove useful for chloride channel patients. Delayed exercise protocols or exposure to cold may prove useful for patients with sodium mutations.

Regardless of these limitations, the NDM population as a whole shows abnormalities on QMA testing, and simple parameters like changes in 90% to 5% relaxation time or peak force would be useful for the majority of NDM patients. The sample size estimate of 50 subjects for a cross-over design is still a large number for a rare disease like NDM, but this standardized, automated protocol makes this technique feasible for use at multiple sites in multiple countries.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge E.L Logigian MD and R.T. Moxley III MD of the University of Rochester Medical Center for their work developing and testing the QMA system as a tool for quantifying handgrip myotonia. The authors also acknowledge A.W. Wiegner PhD of Harvard Medical School for his work developing the customized software used for analysis in this study.

Abbreviations

- CINCH

Consortium for Clinical Investigation of Neurological Channelopathies

- CMAP

Compound muscle action potential

- COV

coefficient of variation

- DM1

myotonic dystrophy type 1

- DM2

myotonic dystrophy type 2

- MC

myotonia congenita

- MVIC

maximum voluntary isometric contraction

- NDM

non-dystrophic myotonia

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- PMC

paramyotonia congenita

- QMA

quantitative muscle assessment

Additional Authors Appendix

The Consortium of Clinical Investigation on Neurologic Channelopathies (CINCH)

Steering Committee: Principal Investigator: Richard J Barohn, MD (Kansas City, KS); Site Principal Investigators: Anthony A. Amato, MD (Boston, MA), Robert C Griggs, MD (Rochester, NY), Stephen C Cannon, MD, PhD (Dallas, TX), Michael Hanna, MD (London, UK), Shannon Venance, MD (London, ON); Chief Statistician: Brian N Bundy, PhD (Tampa, FL); Study Coordinator at Lead Site: Laura Herbelin, BS (Kansas City, KS); CINCH Lead Research Coordinator: Kimberly Hart (Rochester, NY); and CINCH Program Manager: Barbara Herr, MS (Rochester, NY). Investigators/CINCH Trainees: Yunxia Wang, MD (Kansas City, KS), David Saperstein, MD (Kansas City, KS), Jeffrey Statland, MD (Rochester, NY), Doreen Fiahlo, MD (London, UK), Emma Matthews, MD (London, UK), Dipa Raja Rayan, MD (London, UK), Mohammad Salajegheh, MD (Co-Principal investigator, Boston, MA), Ronan Walsh, MD (Boston, MA), Jaya Trivedi, MD (Co-Principal Investigator, Dallas, TX), Angelika Hahn, MD (Co-Principal Investigator, London, ON), James Cleland, MD (Rochester, NY), Paul Twydell, DO (Rochester, NY). Data Management and Coordinating Center Principal Investigator: Jeffrey Krischer, PhD (Tampa, FL). Clinical Evaluators: Laura Herbelin, BS (Kansas City, KS), Merideth Donlan PT, (Boston, MA), Rhonda McLin, PTA(Dallas, TX), Shree Pandya, PT, MS, Katy Eichinger, PT, DPT, NCS (Rochester NY), Karen Findlater, PT (London, ON), Liz Dewar PT (London UK). Clinical Coordinators: Laura Herbelin, BS (Kansas City, KS), Kristen Roe (Boston, MA), Nina Gorham (Dallas, TX), Christine Piechowicz (London, ON), Kimberly Hart (Rochester, NY). Participating Members of the Data Management and Coordinating Center: Joseph Gomes (Tampa, FL), Holly Ruhlig, MS, ARNP, CCRC (Tampa, FL), Bonnie Patterson, BA CCRP (Tampa, FL), David Cuthbertson, MS (Tampa, FL), Rachel Richesson, PhD, MPH (Tampa, FL), and Jennifer Lloyd (Tampa, FL).

Footnotes

Disclosures

This project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Institutes of Health through Grant Number U54 NS059065-05S1.

Additional funding was provided in part by the University of Kansas Medical Center CTSA grant UL1 RR 033179 NCRR/NIH, the University of Rochester CTSA grant UL1 RR 024160 NCRR/NIH, and the University of Texas Southwestern CTSA grant UL1 RR 024982 NCRR/NIH. Brian Bundy’s contribution to this work was supported by Grant Number RR019259 from the NCRR, an NIH component, and the Office of Rare Diseases. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or ORD or NIH.

References

- 1.Ebers GC, George AL, Barchi RL, Ting-Passador SS, Kallen RG, Lathrop GM, Beckmann JS, Hahn AF, Brown WF, Campbell RD, et al. Paramyotonia congenita and hyperkalemic periodic paralysis are linked to the adult muscle sodium channel gene. Ann Neurol. 1991;30(6):810–816. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontaine B, Khurana TS, Hoffman EP, Bruns GA, Haines JL, Trofatter JA, Hanson MP, Rich J, McFarlane H, Yasek DM, et al. Hyperkalemic periodic paralysis and the adult muscle sodium channel alpha-subunit gene. Science. 1990;250(4983):1000–1002. doi: 10.1126/science.2173143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.George AL, Jr, Crackower MA, Abdalla JA, Hudson AJ, Ebers GC. Molecular basis of Thomsen’s disease (autosomal dominant myotonia congenita) Nat Genet. 1993;3(4):305–310. doi: 10.1038/ng0493-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koch MC, Steinmeyer K, Lorenz C, Ricker K, Wolf F, Otto M, Zoll B, Lehmann-Horn F, Grzeschik KH, Jentsch TJ. The skeletal muscle chloride channel in dominant and recessive human myotonia. Science. 1992;257(5071):797–800. doi: 10.1126/science.1379744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ptacek LJ, Trimmer JS, Agnew WS, Roberts JW, Petajan JH, Leppert M. Paramyotonia congenita and hyperkalemic periodic paralysis map to the same sodium-channel gene locus. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;49(4):851–854. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper RG, Stokes MJ, Edwards RH. Physiological characterisation of the “warm up” effect of activity in patients with myotonic dystrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51(9):1134–1141. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.9.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zwarts MJ, van Weerden TW. Transient paresis in myotonic syndromes. A surface EMG study. Brain. 1989;112 ( Pt 3):665–680. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.3.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colding-Jorgensen E. Phenotypic variability in myotonia congenita. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32(1):19–34. doi: 10.1002/mus.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trip J, Drost G, Ginjaar I, Nieman F, van der Kooi AJ, de Visser M, van Engelen BG, Faber C. Redefining the clinical phenotypes of non-dystrophic myotonic syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.162396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heine R, Pika U, Lehmann-Horn F. A novel SCN4A mutation causing myotonia aggravated by cold and potassium. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2(9):1349–1353. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.9.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lerche H, Heine R, Pika U, George AL, Jr, Mitrovic N, Browatzki M, Weiss T, Rivet-Bastide M, Franke C, Lomonaco M, et al. Human sodium channel myotonia: slowed channel inactivation due to substitutions for a glycine within the III-IV linker. J Physiol. 1993;470:13–22. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Day JW, Ricker K, Jacobsen JF, Rasmussen LJ, Dick KA, Kress W, Schneider C, Koch MC, Beilman GJ, Harrison AR, Dalton JC, Ranum LP. Myotonic dystrophy type 2: molecular, diagnostic and clinical spectrum. Neurology. 2003;60(4):657–664. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000054481.84978.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricker K, Koch MC, Lehmann-Horn F, Pongratz D, Otto M, Heine R, Moxley RT., 3rd Proximal myotonic myopathy: a new dominant disorder with myotonia, muscle weakness, and cataracts. Neurology. 1994;44(8):1448–1452. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.8.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ricker K, Haass A, Rudel R, Bohlen R, Mertens HG. Successuful treatment of paramyotonia congenita (Eulenburg): muscle stiffness and weakness prevented by tocainide. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1980;43(3):268–271. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.43.3.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ricker K, Moxley RT, 3rd, Heine R, Lehmann-Horn F. Myotonia fluctuans. A third type of muscle sodium channel disease. Arch Neurol. 1994;51(11):1095–1102. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540230033009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Logigian EL, Blood CL, Dilek N, Martens WB, Moxley RTt, Wiegner AW, Thornton CA, Moxley RT., 3rd Quantitative analysis of the “warm-up” phenomenon in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32(1):35–42. doi: 10.1002/mus.20339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Logigian EL, Martens WB, Moxley RTt, McDermott MP, Dilek N, Wiegner AW, Pearson AT, Barbieri CA, Annis CL, Thornton CA, Moxley RT., 3rd Mexiletine is an effective antimyotonia treatment in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Neurology. 2010;74(18):1441–1448. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dc1a3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moxley RT, 3rd, Logigian EL, Martens WB, Annis CL, Pandya S, Moxley RTt, Barbieri CA, Dilek N, Wiegner AW, Thornton CA. Computerized hand grip myometry reliably measures myotonia and muscle strength in myotonic dystrophy (DM1) Muscle Nerve. 2007;36(3):320–328. doi: 10.1002/mus.20822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Logigian EL, Moxley RTt, Blood CL, Barbieri CA, Martens WB, Wiegner AW, Thornton CA, Moxley RT., 3rd Leukocyte CTG repeat length correlates with severity of myotonia in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Neurology. 2004;62(7):1081–1089. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118206.49652.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sansone V, Marinou K, Salvucci J, Meola G. Quantitative myotonia assessment: an experimental protocol. Neurol Sci. 2000;21(5 Suppl):S971–974. doi: 10.1007/s100720070012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fialho D, Schorge S, Pucovska U, Davies NP, Labrum R, Haworth A, Stanley E, Sud R, Wakeling W, Davis MB, Kullmann DM, Hanna MG. Chloride channel myotonia: exon 8 hot-spot for dominant-negative interactions. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 12):3265–3274. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthews E, Fialho D, Tan SV, Venance SL, Cannon SC, Sternberg D, Fontaine B, Amato AA, Barohn RJ, Griggs RC, Hanna MG. The non-dystrophic myotonias: molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 1):9–22. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drost G, Blok JH, Stegeman DF, van Dijk JP, van Engelen BG, Zwarts MJ. Propagation disturbance of motor unit action potentials during transient paresis in generalized myotonia: a high-density surface EMG study. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 2):352–360. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.2.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Beekvelt MC, Drost G, Rongen G, Stegeman DF, Van Engelen BG, Zwarts MJ. Na+-K+-ATPase is not involved in the warming-up phenomenon in generalized myotonia. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33(4):514–523. doi: 10.1002/mus.20483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fournier E, Arzel M, Sternberg D, Vicart S, Laforet P, Eymard B, Willer JC, Tabti N, Fontaine B. Electromyography guides toward subgroups of mutations in muscle channelopathies. Ann Neurol. 2004;56(5):650–661. doi: 10.1002/ana.20241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan SV, Matthews E, Barber M, Burge JA, Rajakulendran S, Fialho D, Sud R, Haworth A, Koltzenburg M, Hanna MG. Refined exercise testing can aid DNA-based diagnosis in muscle channelopathies. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(2):328–340. doi: 10.1002/ana.22238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hogrel JY. Quantitative myotonia assessment using force relaxation curve modelling. Physiol Meas. 2009;30(7):719–727. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/30/7/014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Logigian EL, Twydell P, Dilek N, Martens WB, Quinn C, Wiegner AW, Heatwole CR, Thornton CA, Moxley RT., 3rd Evoked myotonia can be “dialed-up” by increasing stimulus train length in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41(2):191–196. doi: 10.1002/mus.21481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]