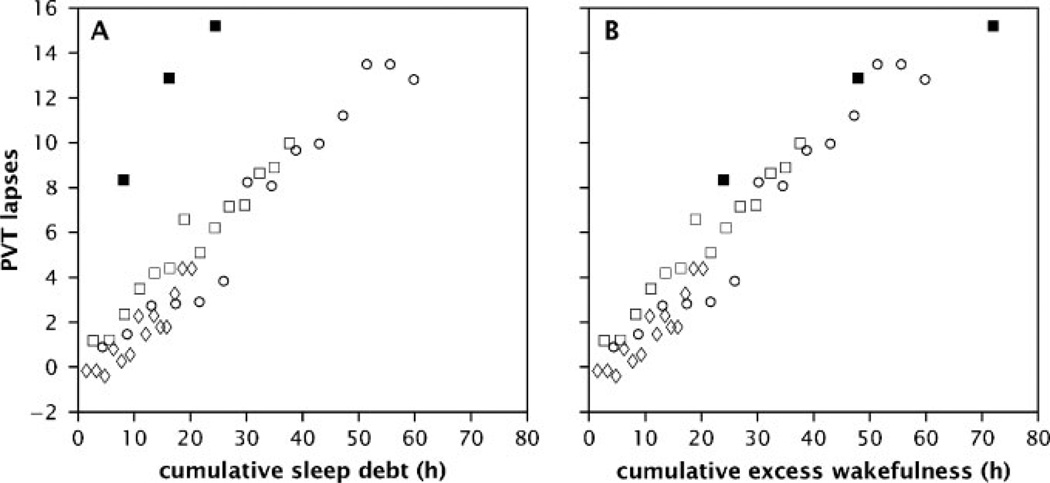

Figure 2.

A graphic comparison of performance on a behavioral alertness test following 14 days of partial sleep restriction or 3 days of total sleep deprivation, as a function of cumulative sleep debt (panel A) or cumulative excess wakefulness (panel B). Alertness was measured by lapses on the Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT). Cumulative sleep debt was determined by summating the difference between a statistically derived average sleep time of 8.16 hour/night and the actual hours of sleep each night (panel A). Cumulative excess wakefulness was determined by summating the difference between a statistically derived average daily wake time of 15.84 hour/day and the actual hours of wake each day (panel B). Each point represents the average time/day for each subject across 14 days of partial sleep restriction or 3 days of total sleep deprivation. Data from three partial sleep restriction groups (8 hours = diamond, 6 hours = square, and 4 hours = open circle) and one total sleep deprivation group (at days 1, 2, and 3 of total sleep deprivation = solid square) are shown. Panel A illustrates a difference (nonlinear relationship) between behavioral performance in the partial sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation groups as a function of cumulative sleep debt. Panel B demonstrates a similarity (linear relationship) between behavioral performance in the partial sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation groups as a function of cumulative excess wakefulness. The difference in analysis between panel A and panel B affects only the total sleep deprivation condition because subjects who receive 0 hours of sleep per day build up a statistically estimated average sleep debt of 8.16 hours per day, but extend their wakefulness by 24 hours per day. Thus, panel B shows a monotonic, near-proportional relationship between cumulative excess wakefulness and neurobehavioral performance deficits. (Reprinted with permission from Van Dongen et al.68)