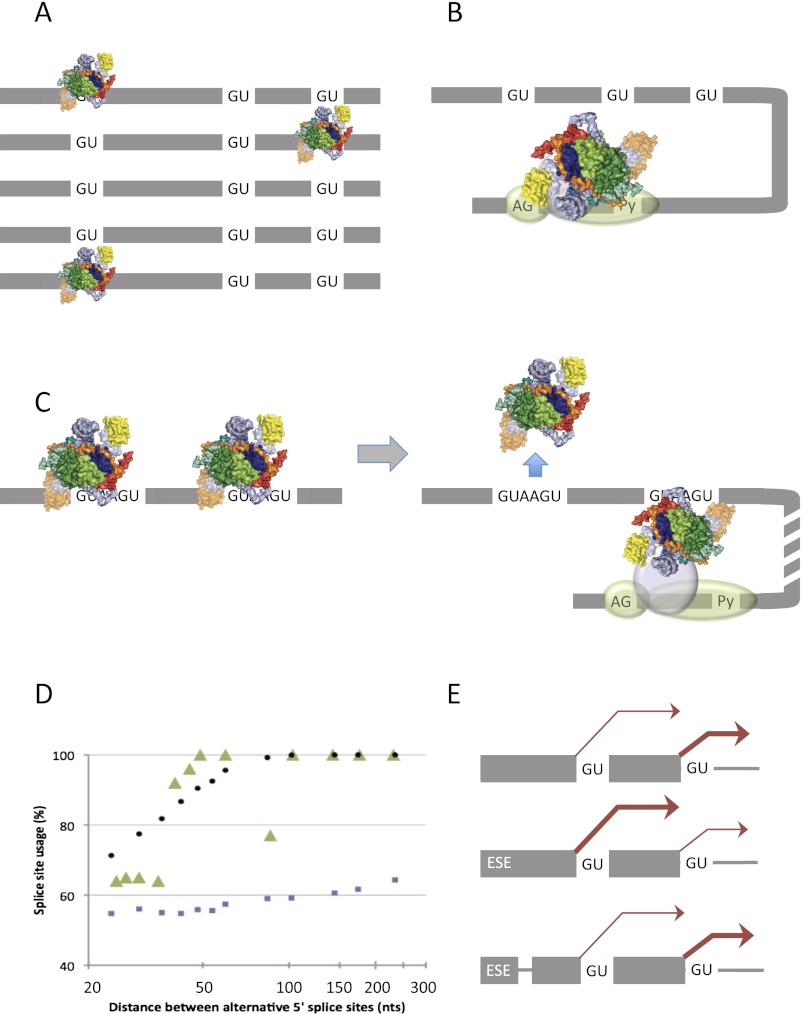

Figure 5.

Models for the effects of affinity for U1 snRNP and 5′ss position upon selection. (A,B) Possible mechanisms by which affinity determines outcome. The candidate 5′ss have low affinity, and the level of occupancy is low such that there is no multiple occupancy and the distribution of U1 snRNPs reflects the affinities for the 5′ss. (A) Independent binding by U1 snRNPs. (B) Recruitment of a single U1 snRNP by components assembled, for example, at the 3′ss and its rapid interactions with the 5′ss result in a distribution of occupancy that reflects the affinities. (C) With high-affinity sites, binding is saturating and there is multiple occupancy (consistent with the model in A) in complex E conditions; during formation of complex A, the intron-proximal U1 snRNP is selected, and the distal snRNP is displaced (Hodson et al. 2012). (D) The effects of varying the distance between two alternative 5′ss suggest that the preference for an intron-proximal site in C is not accounted for by 3D diffusion of free RNA. (Green triangles) Experimental data from Cunningham et al. (1991); (purple squares) outcome expected from simulation with substrate as free RNA (from a distribution of possible conformations of a homogeneous random coil modeled as a freely jointed chain); (black circles) outcomes expected if the sequence between the 5′ss is rigid. From Hodson et al. (2012), by permission of Oxford University Press. (E) Insertion of a non-RNA linker between an ESE and the alternative 5′ss blocks its effects, arguing against a looping model (Lewis et al. 2012).