Abstract

Introduction

A key barrier to identification of tissue biomarkers of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is the heterogeneity of protein expression within tissue. However, by providing spectra for every 0.05 mm2 area of tissue, imaging mass spectrometry (IMS) reveals the spatial distribution of peptides. We sought to determine whether this approach could be used to identify and map protein signatures of ccRCC.

Methods

We constructed two tissue microarrays (TMA) with two cores each of matched tumor and normal tissue from nephrectomy specimens of 70 patients with ccRCC. Samples were analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MS). Peptide signatures were identified within each TMA that differentiated cancer from normal tissue and then cross-validated. MS/MS sequencing was performed to determine identities of select differentially expressed peptides, and immunohistochemistry was used for validation.

Results

Peptide signatures were identified that demonstrated a classification accuracy within each TMA of 94.7–98.5% for each 0.05mm2 spot (spectrum) and 96.9–100% for each tissue core. Cross-validation across TMA's revealed classification accuracies of 82.6–84.7% for each spot and 88.9–92.4% for each core. We identified vimentin, histone 2A.X, and alpha-enolase as proteins with greater expression in cancer tissue, and validated this by immunohistochemistry.

Conclusions

IMS was able to identify and map specific peptides that accurately distinguished malignant from normal renal tissue, demonstrating its potential as a novel, high-throughput approach to ccRCC biomarker discovery. Given the multiple pathways and known heterogeneity involved in tumors such as ccRCC, multiple peptide signatures that maintain their spatial relationships may outperform traditional protein biomarkers.

Keywords: MALDI, imaging mass spectrometry, renal cell carcinoma, biomarkers, proteomics

Introduction

The identification of biomarkers that can facilitate the early diagnosis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), assist with prognosis, and identify early tumor recurrence could substantially improve the diagnosis and management of this disease. A number of potentially important molecular markers of RCC have been identified, yet none have found clinical application.1,2 Despite advances in proteomics technologies over the past decade, important barriers to ccRCC biomarker discovery remain. First, the heterogeneity of protein expression both between and within tumors creates a challenge since most tissue-based assays for rely on tissue homogenization.3,4 Second, given the numerous molecular pathways that impact tumorigenesis, it is unlikely that a single gene or protein with wide applicability as a ccRCC biomarker exists. More likely, a panel of molecular markers or a proteomic signature consisting of multiple differentially expressed peptides will be necessary to obtain sufficient specificity for clinical use.5

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization imaging mass spectrometry (MALDI IMS) is a new proteomics technology with substantial promise for addressing key challenges in biomarker discovery. Similar to other mass spectrometry (MS) approaches, MALDI IMS enables tissue analysis without predetermined protein targets. Unique to this technology, however, is the ability to maintain tissue integrity and localize the expression of any protein or peptide peak within the tissue.6–8 In order to image a tissue section, a laser scans the tissue slide and generates a full mass spectrum at each pre-defined coordinate. Interrogating the tissue in 0.05 mm2 increments, a single 0.5 mm diameter tissue core may have up to 14 distinct MS profiles mapped in detail. Expression maps of peptide peaks corresponding to specific mass to charge (m/z) ratios can then be digitally constructed, depicting both the intensity and location of any given peak. In this way, a single section of tissue becomes a “heat map” with peptide expression data localized to distinct sites. This technology has assisted with biomarker discovery in prostate, liver, lung, and brain cancers.8–12

Whereas prior studies investigating potential ccRCC peptide signatures have relied upon homogenized tissue, the goal of the present study was to determine whether peptide signatures of ccRCC could be determined while maintaining spatial integrity of the tissue. We hypothesized that use of MALDI IMS would enable the identification of peptide signatures of ccRCC. To test this, we utilized MALDI IMS to analyze tissue microarrays (TMAs) containing both ccRCC and matched normal renal tissue.

Methods

We constructed two TMAs, both containing two cores each of matched tumor and normal tissue from nephrectomy specimens of 35 patients with ccRCC. The total cohort therefore consisted of 70 patients (35 associated with each TMA). A hematoxylin and eosin-stained slide of each TMA was reviewed by a genitourinary pathologist (O.F.) to confirm the appropriate tissue was represented for each core. Clinical data including age, sex, race, stage, and grade was collected from each patient and matched to each core. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the development and analysis of the ccRCC TMAs.

On-tissue Digestions

After mounting sections on a conductive glass slide, they were deparaffinized using xylene and graded ethanol prior to heat induced antigen retrieval. The slides were immersed in 10mM Tris pH 9.0 and placed in a Biocare Medical Decloaking Chamber for 20 min at 95°C. The slides were then buffer exchanged to water through 5 changes and allowed to thoroughly dry in a desiccator.

A trypsin (Promega, sequencing grade) working solution was made by diluting 100μL of a stock solution (0.5μg/mL in 100mM acetic acid) in 500μL of 100mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 7.6 with 60μL of acetonitrile. Trypsin was applied in an array with 250μm spacing to the TMA using a Portrait 630 acoustic robotic microspotter (Labcyte, Sunnyvale, CA). 40 drops of trypsin were applied in flyby mode of one drop per pass. An incubation time of 90 seconds was used between passes. Upon completion of trypsin application, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (10mg/mL in 1:1 acetontrile: 0.2% trifluoroacetic acid) was applied to the same array in 40 passes of 1 drop. No incubation time was used. Each applied drop had a volume of ~160pL and final spot diameter on tissue of~180μm was achieved.

Mass Spectral Imaging

Mass spectral data were acquired from the entire TMA using a Bruker Autoflex Speed mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA) operated in positive ion reflectron mode over the m/z range 600–4500. A total of 1600 laser shots were acquired from each pixel in 50 shot increments using a random walk raster to sample the entire matrix spot. Ion images were assembled and visualized using FlexImaging 2.1 (Bruker Daltonics). Digital images of the stained TMAs were acquired using a Mirax Scan (Mirax, Budapest, Hungary) digital slide scanner and were used to select the region(s) of analysis in each core. Areas of the ccRCC cores without tumor were excluded from analysis, and glomeruli were excluded from control cores.

MS/MS Sequencing of Peptides

MALDI MS/MS data of selected peptides were acquired directly from the TMA section using a Bruker UltrafleXtreme mass spectrometer. Spectra were processed using FlexAnalysis 3.0 (Bruker Daltonics). After processing, spectra were loaded into BioTools (Bruker Daltonics) and MASCOT (Matrix Science, Boston, MA) and searched against the Swiss-Prot human database. Searches were carried out with a parent and fragment ion mass tolerance of 0.5 Da. Up to 2 missed tryptic cleavages were allowed and variable modifications included N-terminal and lysine side chain acetylation, oxidation of methionine, tryptophan and histidine, and deamidation of glutamine and asparagine. Matches to search results are reported as a probability based Mowse score. For each peptide, a threshold score for significance is reported which corresponds to a p-value of less than 0.05. Peptides with a Mowse score higher than this threshold value are considered confidently identified.

Immunohistochemistry

TMA sections mounted on slides were deparaffinized, and heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed. The primary antibodies targeted vimentin (VIM, 1:1000 dilution; Dako, Carpintenaria, CA), alpha-enolase (ENO1, 1:100 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and histone 2A family member X (H2AFX, 1:500 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, MA). For vimentin immunostaining, the Bond Polymer Refine detection system was used for visualization. For alpha enolase and H2AFX, slides were incubated with a biotinylated swine anti-rabbit secondary antibody and stained using the Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories). Cores were scored on a scale of 0–12 according to the German Immunoreactive Score.13 Total score is calculating by scoring the percentage of immunoreactive cells on a scale of 0–4 and the staining intensity on a scale of 0–3. The quantity and intensity scores are multiplied to give the total score. For control cores, scores were based on proximal and distal tubule immunostaining.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using ClinProTools 2.2 (Bruker Daltonics). Spectra were loaded into classes and subjected to baseline correction using convex hull algorithm using a flatness of 0.8. All spectra were normalized to total ion current. Peak selection was carried out manually on the monoisotopic peak of the peptide. Classification models were generated using the Genetic Algorithm (GA), and the optimal number of peaks in the model was determined automatically. The GA used a mutation rate of 0.2, a crossover rate of 0.5 and a maximal number of generations of 50. The algorithm was internally validated using a leave-20%-out cross validation over 10 iterations and independently validated on the other TMA. Class images were generated by running all spectra through the classification models and the results loaded into FlexImaging for display. Immunohistochemical scores were compared between cancer and control cores using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Results

The clinical and pathologic characteristics of the 70 patients in the study cohort are given in Table 1. Over 90% of patients were White and 80% were male. Patients primarily had T1–T3 disease, and most patients had localized cancer. There were no significant differences in clinicopathologic variables between the two TMAs. Four tissue cores from each patient were sampled—two tumor and two matched normal specimens—for a total of 280 cores analyzed.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathologic characteristics of the patients in each of the TMAs. P values from Fisher's exact tests.

| All | TMA 1 | TMA 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | % | n | % | n | % | p |

| All | 70 | 100% | 35 | 50% | 35 | 50% | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 14 | 20% | 26 | 74% | 30 | 86% | |

| Male | 56 | 80% | 9 | 26% | 5 | 14% | 0.37 |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 64 | 91% | 31 | 89% | 33 | 94% | |

| Black | 6 | 9% | 4 | 11% | 2 | 6% | 0.67 |

| pTstage | |||||||

| T1 | 24 | 34% | 13 | 37% | 11 | 31% | |

| T2 | 14 | 20% | 8 | 23% | 6 | 17% | |

| T3 | 28 | 40% | 11 | 31% | 17 | 49% | |

| T4 | 4 | 6% | 3 | 9% | 1 | 3% | 0.47 |

| N stage | |||||||

| N0 | 65 | 93% | 32 | 91% | 33 | 94% | |

| N+ | 5 | 7% | 3 | 9% | 2 | 6% | 1 |

| M Stage | |||||||

| M0 | 57 | 81% | 28 | 80% | 29 | 83% | |

| M+ | 13 | 19% | 7 | 20% | 6 | 17% | 1 |

| Grade | |||||||

| I | 7 | 10% | 4 | 11% | 3 | 9% | |

| II | 34 | 49% | 20 | 57% | 14 | 40% | |

| III | 20 | 29% | 8 | 23% | 12 | 34% | |

| IV | 9 | 13% | 3 | 9% | 6 | 17% | 0.43 |

| Margins | |||||||

| Negative | 65 | 93% | 32 | 91% | 33 | 94% | |

| Positive | 5 | 7% | 3 | 9% | 2 | 6% | 1 |

We performed MALDI MS on both TMAs and acquired 6019 individual mass spectra. An average of approximately 500 peptides were observed in the mass spectrum from each 0.05mm2 spot, and ~12 spots were analyzed from each 0.5mm diameter tissue core on average. Figure 1 shows an H&E stain of TMA1, and the expression of the 944.9 Da peptide peak is mapped according to the relative intensity of this peptide across each core. Similar spatial expression maps could be generated for any peptide peak.

Figure 1.

(A) H&E of TMA 1 shown next to (B) MALDI-TOF IMS image of 944.9 Da peptide peak.

We next compared peptide expression in ccRCC and normal parenchyma, and this revealed multiple individual peptides that discriminated between malignant and control renal tissue with a high degree of accuracy. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis revealed four peptides from TMA1 that identified malignant tissue with >90% accuracy (area under the curve [AUC] 0.90–0.94), and ROC analysis of TMA2 revealed five peptides with AUC>90% (0.90–0.94). Additionally, the ability to map peptide expression within a single core is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows the expression map of four peptides in a core containing both benign and malignant tissue. ROC curves demonstrating the accuracy of each of these peptides in distinguishing cancer from control are also depicted.

Figure 2.

Images of a single core from TMA 2. A) H&E stained section of the core with a schematic indicating cancer and normal areas within the core. B) Four different ion images from the same core showing peptides that localize to the cancer portion of the core. C) Receiver operating characteristic curves for the same 4 peptides along with calculated area under the curve for each.

In order to identify the set of peptides within each TMA that accurately differentiated ccRCC from normal kidney, we compared the average spectra for cancer versus normal cores in each TMA (Figure 3) and utilized the GA to identify the signature of peptide peaks with the greatest classification accuracy. The peptide signature obtained from TMA1 consisted of 7 peptides (Table 2), and, after internal validation, demonstrated an accuracy of 94.4% and 95.0% for correctly assigning each spot as control or cancer, respectively (Table 3). The peptide signature obtained from TMA2 consisted of 12 peptide peaks and demonstrated 100% accuracy for control and 96.9% accuracy for ccRCC spots. These classifications are visually depicted in Figure 4, which shows the classification maps of each core juxtaposed with schematic representations of tissue type.

Figure 3.

Selected segment of the average spectra for cancer and control from TMA 2. Two peaks (m/z 1429.1 and 1571.2) that differed in intensities between the groups are highlighted.

Table 2.

List of peptide peaks (units=Daltons) comprising each TMA

| TMA1 | TMA2 |

|---|---|

| 2187.90 | 933.67 |

| 2597.31 | 830.55 |

| 3131.57 | 1860.25 |

| 1954.90 | 2808.63 |

| 2723.37 | 1098.91 |

| 1702.54 | 1520.21 |

| 1788.62 | 1172.88 |

| 2529.73 | |

| 1988.46 | |

| 1353.08 | |

| 1287.94 | |

| 2151.43 |

Table 3.

Accuracy of proteomics classification according to leave-20%-out internal validation and cross-validation with alternate TMA. Each spectral profile (i.e. each spot) assessed separately.

| Source algorithm | Tissue being classified | Control | RCC | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMA 1 | TMA 1 | 94.4% | 95.0% | 94.7% |

| TMA 2 | TMA 2 | 100.0% | 96.9% | 98.5% |

| Cross validation | ||||

| TMA 1 | TMA 2 | 86.0% | 79.1% | 82.6% |

| TMA 2 | TMA 1 | 85.6% | 83.7% | 84.7% |

Figure 4.

Proteomics classification of TMA 1 (A) and TMA 2 (B), each is shown adjacent to schematic representations of cores. RCC=red, control=green.

In order to validate the predictive accuracy of the peptide signatures, each classification algorithm was cross-validated using the alternate TMA. Thus, TMA2 served as the external validation cohort for TMA1, and TMA1 was the external validation cohort for TMA2. The predictive accuracy in these cross-validation models ranged from 79.1–86.0% (Table 3). Finally, we sought to assess the predictive accuracy of these peptide signatures in classifying entire cores as malignant or benign. This was done in order to parallel the more clinically applicable scenario in which a single diagnosis is required rather than a detailed map of cancer vs. non-cancer within a tissue specimen. The classification of a given core was considered correct when ≥50% of the assayed spots within that core were accurately assigned. Both the internal validation and external validation approaches were used for this analysis, with accuracies ranging from 98.5–100% for the internal validation models and 91.3–93.9% for external validation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Accuracy of whole-core proteomics classification and cross-validation.

| Source algorithm | Tissue being classified | Type | Correctly assigned cores | Total cores | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMA 1 | TMA 1 | Control | 64 | 65 | 98.5% |

| RCC | 62 | 62 | 100.0% | ||

| Total | 126 | 127 | 99.2% | ||

| TMA 1 | TMA 2 | Control | 63 | 69 | 91.3% |

| RCC | 62 | 66 | 93.9% | ||

| Total | 125 | 135 | 92.6% | ||

| TMA 2 | TMA 1 | Control | 61 | 65 | 93.8% |

| RCC | 58 | 62 | 93.5% | ||

| Total | 119 | 127 | 93.7% | ||

| TMA 2 | TMA 2 | Control | 69 | 69 | 100.0% |

| RCC | 66 | 66 | 100.0% | ||

| Total | 135 | 135 | 100.0% |

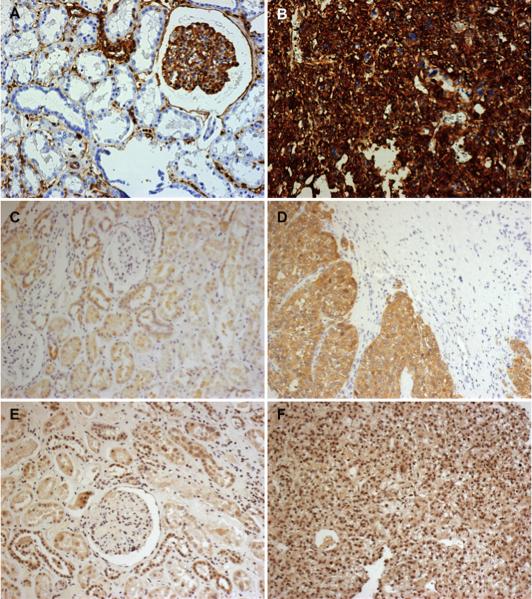

A number of peptides were selected for MALDI MS/MS sequencing based on their differential expression in ccRCC and control tissue. This was performed in order to assess the capacity to identify biomarkers based on the results of MALDI IMS. The sequencing analysis identified six proteins with a high degree of confidence (Table 5). As an additional validation measure, we selected three of these—vimentin, alpha-enolase, and H2AFX—and performed immunohistochemistry (Figure 5). For each of these proteins, staining was significantly greater in ccRCC compared to controls, recapitulating the results of the MALDI IMS (Table 6).

Table 5.

Protein identities of selected peptides obtained by MALDI MS/MS. Matches to search results are reported as pro based Mowse score.

| Mass (Da) | Sequence | Protein ID | Mowse Score | ID threshold score | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 944.59 | AGLQFPVGR + Deamidated (NQ) | Histone H2A.x | 52 | 42 | 0.007 |

| 1274.65 | LLVVYPWTQR | Hemoglobin subunit beta | 41 | 37 | 0.020 |

| 1529.77 | VGAHAGEYGAEALER | Hemoglobin subunit alpha | 87 | 43 | <0.001 |

| 1571.18 | ISLPLPNFSSLNLR | Vimentin | 50 | 43 | 0.012 |

| 1804.71 | AAVPSGASTGIYEALELR | Alpha enolase | 86 | 38 | <0.001 |

| 1836.25 | QEPSQGTTTFAVTSILR | Ig alpha-1 chain C region | 108 | 44 | <0.001 |

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry showing increased expression of vimentin, alpha-enolase, and histone 2A.X in RCC compared to normal cores. The cores on the left of the figure represent normal tissue and show staining for vimentin (A, score=3), alpha-enolase (C, score=4), and histone 2A.X (E, score=4).The cores on the right show expression of these markers in RCC: vimentin (B, score=12), alpha-enolase (D, score=8), histone2A.X (F, score=12). All magnifications 20×.

Table 6.

Differences in German Immunoreactive Scores between cancer and control tissue.

| Score [median [IQR]) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Control | Cancer | p |

| Vimentin | 0 (0–3) | 9 (4–12) | <0.001 |

| Alpha-enolase | 4 (4–4) | 8 (4–12) | <0.001 |

| Histone 2A.X | 4 (4–4) | 8 (4–12) | <0.001 |

Discussion

Here we report the first use of MALDI IMS to create a visual map of differentially expressed peptides in ccRCC and subsequently identify peptide signatures that reliably distinguish ccRCC from normal renal tissue. Two signature profiles were identified—one from each TMA—and each showed a high degree of accuracy upon external validation in the alternate TMA. When cores in the independent validation cohort were classified in their entirety as ccRCC or control, 85.5–92.4% of cores were correctly assigned. MALDI MS/MS was then used to sequence a subset of differentially expressed peptides, and a number of proteins were successfully identified. We further validated three of these using immunohistochemistry.

The ability to accurately classify microscopic tissue sections based on peptide signatures has important clinical implications. Percutaneous renal mass biopsy is frequently ambiguous when used to obtain a tissue diagnosis of RCC, and it has not gained widespread use as a result.14 This is particularly critical given the rising incidence of small renal masses, largely attributed to increased use of cross-sectional imaging, in which the likelihood of malignancy is inversely proportional to mass size.15 Due to inaccuracies in the histologic diagnosis of RCC based on the small tissue cores obtained via renal mass biopsy, many patients undergo definitive surgical management without a prior biopsy. There is substantial overlap histologically between the eosinophilic variant of ccRCC, chromophobe RCC, and oncocytoma, and these are at times not distinguishable even by experienced pathologists.16 While individual markers may have limited use as diagnostic tools in light of overlapping staining patterns and heterogeneous protein expression in ccRCC, peptide fingerprinting utilizing a combination of multiple peptides holds substantial promise.17,18 By looking at patterns of peptide expression within tissue—and mapping them to specific locations within the tissue—microscopic specimens may be accurately classified as benign or malignant. As a diagnostic tool, peptide fingerprinting offers the additional potential advantage of obviating the need for protein identification. If a high degree of accuracy can be obtained through a peptide fingerprint, identification of the individual proteins that make up the signature becomes diagnostically unnecessary. Our results, utilizing tissue specimens far smaller than a renal mass biopsy core, suggests MALDI IMS could be utilized for this purpose.

A second feature unique to this approach and with potential clinical implications is the ability to obtain protein identities of peptides found to be differentially expressed in the MALDI IMS analysis. Using MALDI MS/MS, we were able to sequence specific peptides of interest and further confirmed these results via immunohistochemistry. Although vimentin has been previously observed to be upregulated in ccRCC, its identification here is important in validating this approach to biomarker discovery.3,4 Furthermore, two other proteins validated by immunohistochemistry—alpha-enolase and H2AFX—appear to be potentially novel markers of ccRCC.

Recent studies have shown that alpha-enolase, a glycolytic enzyme also known as phosphopyruvate dehydratase, is upregulated in lung, head and neck, and breast cancer.19–21 While alpha-enolase expression is known to be regulated by hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), which plays a key role in the ccRCC oncogenesis, we are not aware of any published reports of alpha-enolase as a potential ccRCC biomarker.22 Several investigations have suggested a possible role for histone 2A in genotoxic stress and tumorigenesis, and phosphorylated H2AFX appears to be a marker of activated DNA damage in bladder, breast, lung, and colon cancers.23–25 One report suggested phosphorylated H2AFX expression could be useful in discriminating metastatic RCC from hepatocellular or adrenocortical carcinoma.26 While individual biomarkers may or may not serve a diagnostic purpose on their own, identification of novel markers by MALDI IMS and MS/MS may provide new insights into the pathogenesis of RCC and deserves further study.

A number of different proteomics approaches have been previously utilized to characterize RCC. Employing (2D PAGE) and MS in a comparison of RCC with matched renal parenchyma, Unwin et al. identified multiple proteins with differential expression between cancer and normal tissue.3 Several additional studies have also utilized 2D PAGE to compare matched RCC and normal tissue; however, this approach is limited by both its sensitivity and low throughput nature.27,28 Other mass spectrometry based approaches have looked at RCC tissue itself or tumor interstitial fluid to identify markers of RCC.4,29 Unlike IMS, however, these techniques do not provide spatial information regarding protein expression in situ. Some studies have performed laser capture microdissection in order to evaluate relatively uniform samples, but this technique does not offer the high-throughput advantages of MALDI IMS.3,30

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, the total cohort size is relatively small, numbering 70 patients, with the control group comprised of normal tissue from kidneys with ccRCC. It is unknown whether a larger patient sample would enable identification of a more homogenous peptide signature based on the two TMAs. Additionally, Only patients with ccRCC were included in this analysis, therefore we are unable to identify signatures consistent with different histologies in the present analysis. Further work is planned in order to better understand molecular differences between ccRCC subtypes. In addition, one concern of using matched normal samples is the known field effect in ccRCC, with adjacent histologically normal tissue expressing some molecular characteristics that are consistent with tumor.6 While the matched normal cores for the TMAs were generally obtained from healthy kidney that was distant from the tumor, the distance from the normal core to the tumor was not recorded. However, any similarities between the ccRCC and control samples as a result of this effect would bias these findings towards the null. Furthermore, while protein profiles of normal tissue may depend on the cell type represented in the small tissue section, this replicates the kind of material that would be obtained in a renal biopsy. Another important limitation is the difficulty in obtaining protein identities on some of the differentially expressed peptides that accurately classified tissue as benign or malignant. This technical limitation slows the identification of novel biomarkers using MALDI IMS; however, we are continuing to work towards identifying more of these differentially expressed peptides. Nevertheless, in this study we have established a signature that accurately differentiates ccRCC from control and have identified six differentially expressed peptides, suggesting IMS has promise for identifying multiple biomarkers of ccRCC.

Conclusions

These data demonstrate the utility of MALDI IMS both in defining peptide signatures of ccRCC and in identifying specific tissue markers of ccRCC. The capacity to rapidly analyze ccRCC tissue microarrays and create a spatial map of differentially expressed peptides provides tremendous opportunities for biomarker discovery. In addition, we found that the peptide signatures themselves can differentiate benign from malignant tissue with a high degree of accuracy, potentially offering a novel approach to improving the utility of renal mass biopsy. Further work may help define prognostic signatures in patients with ccRCC.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs. David Hachey and Kevin Schey for their contributions to this manuscript.

Supported by Vanderbilt CTSA grant 1 UL1 RR024975 from the NIH; by K08 CA113452(PEC) from the NIH; by NIH/NIGMS 5R01 GM58008 (RMC); by DOD W81XWH-05-1-0179(RMC); and by Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center Core Support Grant P30 CA68485(RMC).

Key of definitions

- AUC

Area under the curve

- GA

Genetic Algorithm

- IMS

Imaging mass spectrometry

- MALDI

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- RCC

Renal cell carcinoma

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- TMA

Tissue microarray

- 2D Page

Two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: DISCLAIMER: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our subscribers we are providing this early version of the article. The paper will be copy edited and typeset, and proof will be reviewed before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to The Journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barocas DA, Rohan SM, Kao J, et al. Diagnosis of renal tumors on needle biopsy specimens by histological and molecular analysis. J Urol. 2006;176:1957–1962. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eichelberg C, Junker K, Ljungberg B, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic molecular markers for renal cell carcinoma: a critical appraisal of the current state of research and clinical applicability. Eur Urol. 2009;55:851–863. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unwin RD, Craven RA, Harnden P, et al. Proteomic changes in renal cancer and co-ordinate demonstration of both the glycolytic and mitochondrial aspects of the Warburg effect. Proteomics. 2003;3:1620–1632. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siu KWM, DeSouza LV, Scorilas A, et al. Differential protein expressions in renal cell carcinoma: new biomarker discovery by mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:3797–3807. doi: 10.1021/pr800389e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanjmyatav J, Steiner T, Wunderlich H, et al. A specific gene expression signature characterizes metastatic potential in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2011;186:289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oppenheimer SR, Mi D, Sanders ME, et al. Molecular analysis of tumor margins by MALDI mass spectrometry in renal carcinoma. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:2182–2190. doi: 10.1021/pr900936z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herring KD, Oppenheimer SR, Caprioli RM. Direct tissue analysis by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry: application to kidney biology. Semin Nephrol. 2007;27:597–608. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Faouder J, Laouirem S, Chapelle M, et al. Imaging Mass Spectrometry Provides Fingerprints for Distinguishing Hepatocellular Carcinoma from Cirrhosis. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:3755–3765. doi: 10.1021/pr200372p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz SA, Weil RJ, Thompson RC, et al. Proteomic-based prognosis of brain tumor patients using direct-tissue matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7674–7681. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cazares LH, Troyer D, Mendrinos S, et al. Imaging mass spectrometry of a specific fragment of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase kinase 2 discriminates cancer from uninvolved prostate tissue. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5541–5551. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amstalden van Hove ER, Blackwell TR, Klinkert I, et al. Multimodal mass spectrometric imaging of small molecules reveals distinct spatio-molecular signatures in differentially metastatic breast tumor models. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9012–9021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanagisawa K, Shyr Y, Xu BJ, et al. Proteomic patterns of tumour subsets in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2003;362:433–439. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Remmele W, Schicketanz KH. Immunohistochemical determination of estrogen and progesterone receptor content in human breast cancer. Computer-assisted image analysis (QIC score) vs. subjective grading (IRS) Pathol. Res. Pract. 1993;189:862–866. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)81095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leveridge MJ, Finelli A, Kachura JR, et al. Outcomes of small renal mass needle core biopsy, nondiagnostic percutaneous biopsy, and the role of repeat biopsy. Eur Urol. 2011;60:578–584. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsivian M, Mouraviev V, Albala DM, et al. Clinical predictors of renal mass pathological features. BJU Int. 2011;107:735–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abrahams NA, MacLennan GT, Khoury JD, et al. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: a comparative study of histological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features using high throughput tissue microarray. Histopathology. 2004;45:593–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.02003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chinello C, Gianazza E, Zoppis I, et al. Serum biomarkers of renal cell carcinoma assessed using a protein profiling approach based on ClinProt technique. Urology. 2010;75:842–847. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lichtenfels R, Dressler SP, Zobawa M, et al. Systematic comparative protein expression profiling of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a pilot study based on the separation of tissue specimens by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:2827–2842. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900168-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang G-C, Liu K-J, Hsieh C-L, et al. Identification of alpha-enolase as an autoantigen in lung cancer: its overexpression is associated with clinical outcomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5746–5754. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai S-T, Chien I-H, Shen W-H, et al. ENO1, a potential prognostic head and neck cancer marker, promotes transformation partly via chemokine CCL20 induction. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1712–1723. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tu S-H, Chang C-C, Chen C-S, et al. Increased expression of enolase alpha in human breast cancer confers tamoxifen resistance in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;121:539–553. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0492-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang BH, Agani F, Passaniti A, et al. V-SRC induces expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and transcription of genes encoding vascular endothelial growth factor and enolase 1: involvement of HIF-1 in tumor progression. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5328–5335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartkova J, Horejsí Z, Koed K, et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nature03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barlési F, Giaccone G, Gallegos-Ruiz MI, et al. Global histone modifications predict prognosis of resected non small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4358–4364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boo LM, Lin HH, Chung V, et al. High mobility group A2 potentiates genotoxic stress in part through the modulation of basal and DNA damage-dependent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-related protein kinase activation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6622–6630. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wasco MJ, Pu RT. Utility of antiphosphorylated H2AX antibody (gamma-H2AX) in diagnosing metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2008;16:349–356. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181577993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarto C, Marocchi A, Sanchez JC, et al. Renal cell carcinoma and normal kidney protein expression. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:599–604. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dallmann K, Junker H, Balabanov S, et al. Human agmatinase is diminished in the clear cell type of renal cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:342–347. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teng P-N, Hood BL, Sun M, et al. Differential Proteomic Analysis of Renal Cell Carcinoma Tissue Interstitial Fluid. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:1333–1342. doi: 10.1021/pr101074p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Craven RA, Banks RE. Laser capture microdissection and proteomics: possibilities and limitation. Proteomics. 2001;1:1200–1204. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200110)1:10<1200::AID-PROT1200>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]