Abstract

We have developed competitive and direct binding methods to examine small-molecule inhibitors of protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPase) activity. Focusing on the Yersinia outer protein H (YopH), a potent bacterial PTPase, we describe how an understanding of the kinetic interactions involving YopH, peptide substrates, and small-molecule inhibitors of PTPase activity can be beneficial for inhibitor screening and we further translate these results into a microarray assay for high-throughput screening.

Keywords: Affinity screening, competitive binding assay, high-throughput screening, protein tyrosine phosphatase, peptide microarray, phosphopeptide, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), Yersinia pestis outer protein H (YopH)

Introduction

Protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPases) catalyze dephosphorylation of substrates involved in a wide range of cellular processes including growth, metabolism, adhesion, and differentiation (1). As such, they have emerged as important therapeutic targets that are directly involved in regulating pathological processes in cancer and infectious diseases. The Yersinia outer protein H (YopH) is a highly active PTPase that is required for infection by Yersinia pestis, the Gram-negative enterobacterium that causes plague. As a general mechanism for PTPases, the phenolic leaving group in the transition state is protonated and catalysis is likely driven by stabilizing the transition state (2). A nucleophilic Cys residue (position 403 in YopH) with a low pKa value forms a thiophosphate intermediate during catalysis which undergoes nucleophilic attack at the amino acid phosphoryl group. Subsequent hydrolysis is assisted by an invariant Asp, which is part of a loop (WPD) in PTPases that closes towards the catalytic pocket during substrate binding (3).

Catalytic activity assays are essential for evaluating the performance of inhibitors that target PTPase function and small-molecule substrates such as para-nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP) are commonly used for screening purposes. However, dephosphorylation by PTPases proceeds by enzyme-substrate docking pathways that may be obscured by assays that focus solely on catalytic function as a means of identifying potential inhibitors. In this regard, peptides and protein substrates are more likely to simulate enzyme-substrate interactions that are important for improving the potency of lead inhibitors acting under physiological conditions. Although peptides are usually unstructured while free in solution, native folds may be recapitulated in the bound state by conformational complementarity (4). Thus, studying the more native-like binding contacts of peptide substrates with PTPases could lead to a better prediction of inhibitor potency in vivo.

Various compounds have previously been reported to inhibit the catalytic activity of YopH (5–12). In addition to effects on catalytic activity, it is important to understand the physical interactions between the PTPase, its substrate(s) and inhibitors. Recently, a series of potent YopH inhibitors ranging from micromolar to nanomolar activity in the pNPP assay (5) were developed by substrate-affinity screening (13) using an oxime-based library of high-affinity nitrophenylphosphate-derived substrates (5). In this report, we investigate the influence of inhibitors derived from the oxime-based library (5) on biomolecular interactions between YopH and a peptide substrate. Using measurements from a surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensor, we describe the binding interactions between the PTPase and a peptide substrate as well as the inhibition of these interactions by small molecules. We also describe a microarray assay that verifies the inhibition of catalytic activity and is amenable to high-throughput screening.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The PTPase domains of YopH and YopH C403A/D356A were prepared as previously described (14). The biotinylated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) peptides biotin-LVDADEpYLIPQQG-COOH and biotin-LVDADEYLIPQQG-COOH were synthesized and HPLC-purified by Biotmatik (Wilmington, Delaware). Peptide purities were greater than 95% (as verified by HPLC), and identities were confirmed by mass spectrometry. Fresh solutions were made before all experiments.

The inhibitors were prepared as previously described (5): (difluoro((3-(4-((((E)-furan-3-ylmethylidene)amino)oxy)methyl)phenyl)phenyl))methyl) phosphonic acid (1); (difluoro((3-(4-((((E)-furan-2-ylmethylidene)amino)oxy)methyl)phenyl)phenyl))methyl) phosphonic acid (2); and 5-((1E)-(((4-(3-(difluoro(phosphono)methyl)phenyl)phenyl) methoxy)imino)methyl)furan-2-carboxylic acid (3).

The reagents 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), ethanolamine-HCl, sodium hydroxide solutions, HBS-EP buffer, glycine-HCl, sodium acetate solution, desorb solutions, 70% glycerol solution, sodium dodecyl sulfate solution (SDS), 10× Flexchip blocking buffer, CM5 chips (research grade), and Whatman FAST nitrocellulose-coated glass slides were purchased from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ). Neutravidin was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL). Mouse anti-pTyr antibody (pTyr-100, #9411) was purchased from Cell Signaling, while goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated to Alexafluor 647 was purchased from Life Technologies, Inc. l-Phenylalanine was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA) and NSC-87877 was purchased from EMD Chemicals (Billerica, MA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Surface plasmon resonance

SPR measurements were performed on a BIACORE 3000 (Biacore, Uppsala, Sweden) at 25 °C. The SPR instrument was cleaned using a ‘desorb’ protocol before each immobilization procedure. A new CM5 sensorchip was then docked and the instrument was primed three times with a solution consisting of 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3.4 mM EDTA, 0.005% polysorbate 20, pH 7.4 (HBS-EP buffer). The CM5 sensorchip was then preconditioned with two 10 µL injections, each of 100 mM HCl, 50 mM NaOH, and 0.05% SDS using a flow rate of 100 µL/min. The detector signal was normalized with a solution of 70% glycerol.

For peptide immobilization, neutravidin (40 µg/mL) diluted in 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.0, was immobilized on flow cells 2 and 4 to a surface density of 1200 RU by using standard EDC/NHS amine-coupling procedures, followed by blocking of remaining amine-reactive NHS-esters with 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.0). Flow cells 1 and 3 were used for references and were subjected to the same amine-coupling procedures as flow cells 2 and 4, but without the injection of neutravidin. Biotinylated pTyr- and Tyr-EGFR peptides, in HBS-EP buffer (0.2 mg/mL) were injected onto flow cells 2 and 4, respectively, using a flow rate of 5 µL/min for 30 s. The amount of captured peptide (approximately 100 RU) was determined after a 1 min stabilization period.

For examining binding kinetics with immobilized peptide, the SPR instrument was primed three times with CBS-P comprised of 10 mM citrate buffer, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% polysorbate 20, pH 6.2, sterile filtered and degassed before each experiment. The YopH C403A/D356A preparation was diluted in CBS-P to concentrations of 0.02 to 2.0 µM, and injected at a flow rate of 50 µL/min for 5 min, followed by buffer for 10 min. The surface was regenerated after each cycle by injecting 10 mM glycine-HCl (pH 1.5) at a flow rate of 30 µL/min for 30 s, followed by 2 min of stabilization in buffer.

For competitive binding experiments, stock solutions of inhibitors were prepared in DMSO and serially diluted (in DMSO) prior to each experiment. The appropriate amount of compound was then added to a solution of YopH (0.5 µM) in CBS-P, for a final DMSO percentage of 5% for 1 and 2, and 3% for 3. The concentration of compounds in each sample ranged from 0.5 – 90 µM. To limit bulk refractive-index changes, the concentration of DMSO in the running buffer matched the amount used for the experimental samples. Baseline signals were established without YopH, using either DMSO in sample buffer or with the compound dissolved in DMSO and diluted into buffer. Flow rates, injection times, and regeneration conditions were the same as described above. Control samples consisting of YopH with the corresponding amount of DMSO were examined before and after testing experimental sample dilutions to confirm complete recovery of YopH binding, as well as to compare the amount of YopH bound. Each inhibitor dilution series was examined in separate but identical experiments to maintain similar incubation times. The amount of bound YopH was estimated from the SPR signal at a fixed time (540 s) just before the end of the injection and the percentage bound, relative to the injection of YopH alone, was calculated. Association and dissociation kinetic rate constants (kon and koff) and the equilibrium dissociation constant KD were calculated using BIAevaluation 4.1 software. Sensorgrams were corrected for background signals by subtracting reference and blank cells. Because the SPR signal is proportional to the amount of analyte bound at the sensor-chip surface, the stoichiometry (S) of the interaction was determined from the equation:

S = Rmax/(RL*(MWA/MWL))

where Rmax = maximum response (RU), RL = amount of ligand bound (RU), MWA = molecular weight of the analyte, and MWL = molecular weight of the ligand. IC50 calculations were performed with OriginPro 8.5.1 software (OriginLab, Northhampton, MA), using the ‘DoseResp’ fitting function.

For examining binding kinetics with immobilized PTPases, solutions of the YopH proteins were prepared in 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5) and immobilized via amine-coupling chemistry to achieve surface densities of approximately 8000 RU. YopH C403A/D356A was immobilized on flow cell 2, while wild-type YopH was immobilized on flow cell 4. Flow cells 1 and 3 were used as reference cells. For direct binding experiments with immobilized protein, the SPR instrument was primed three times with CBS-P containing 3% DMSO. A series of blank samples followed by solutions of each compound at concentrations ranging from 1 to 90 µM (1 – 250 mM for peptides and 1 – 50 mM for pTyr) were injected for 2 min using a flow rate of 30 µL/min, followed by buffer for 5 min at the same flow rate. All samples contained 3% DMSO. Regeneration of the surface was performed at the end of each cycle by injecting 10 mM NaOH for 30 s at 10 µL/min, followed by 4 min of stabilization in buffer using the same flow rate. Each experiment was performed three times using the same sensor chip surface.

Microarrays

Biotinylated peptides (5 mM) were prepared in citrate buffer, pH 6.4, mixed with neutravidin (10 mg/mL in water), using a threefold molar excess of peptide, and incubated for 2 h (22°C). Serial dilutions (500, 400, 300, 200, 100, 75, 50, 25 and 12.5 µM) of the peptide-neutravidin mixture were then prepared in a 96-well plate with citrate buffer and 20% glycerol. Antibody-conjugated Alexafluor 647, EGFR phosphopeptide/neutravidin dilutions, and buffer were spotted in quadruplicate in 12 identical grid blocks onto a Whatman FAST nitrocellulose-coated glass slide via contact printing (BioOdyssey Calligrapher Mini-Arrayer, Bio-Rad, CA), and dried overnight under vacuum.

The slide was first blocked with 5 mL of 1× Flexchip blocking buffer with gentle rocking for 1 h (22°C), and then washed three times with 1× TBS-T (10 mM Tris-buffered saline and 0.3% tween-20). YopH (0.2 µg) was mixed with inhibitor in DMSO (from 1.2 – 800 µM), and incubated for 30 min (22°C). The washed slide was fitted to a 16-well gasket, and the following mixtures were added to the well blocks while the slide was still wet: YopH and inhibitor (800 µM; block 1), YopH and inhibitor (400 µM; block 2), YopH and inhibitor (133 µM; block 3), YopH and inhibitor (44.4 µM; block 4), YopH and inhibitor (14.8 µM; block 5), YopH and inhibitor (4.9 µM; block 6), YopH and inhibitor (1.2 µM; block 7), YopH and 5% DMSO (block 8), YopH and aurintricarboxylic acid (4, 100 µM; block 9), YopH and NSC 87877 (5, 100 µM; block 10), YopH C403A/D356A (0.2 µg/well; block 11), and citrate buffer with 5% DMSO (block 12). The slide was incubated in a dark humid chamber for 5 min (22°C). The slide was then washed three times with TBS-T and incubated for 1 h (22°C) with 5 mL TBS containing mouse anti-pTyr antibody (1:1000). The slide was washed an additional three times with TBS-T followed by incubation for 1 h (22°C) with 5 mL of goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated to Alexafluor 647 (1:2000) in TBS in the dark. The slide was washed three final times with TBS-T and once with water then air-dried.

The array was read with an Axon GenePix 4000B scanner (Molecular Devices, CA), and data were collected with the GenePix Pro software. Normalized inhibition values for wells treated with YopH and inhibitors were calculated as a percentage of the background subtracted intensity of fluorescence values for EGFR phosphopeptide spots in the buffer only block.

Results and Discussion

Interactions between YopH and EGFR phosphopeptide

Peptide substrates

The YopH used in our studies consisted of the active catalytic domain (amino acid residues 164–468), as previously described (15) or a catalytically inactive YopH mutant C403A/D356A of this domain that was designed based on previous reports showing that the double mutation results in a better substrate trapping probe than a mutation of the catalytic Cys403 alone (16, 17). We employed the single catalytic domain in our studies as these do not form the domain-swapping binary complexes previously noted with the full-length YopH protein (18).

Only a few potential targets of YopH in mammalian cells have been tentatively identified. For example, mutants of YopH that were unable to bind p130Cas did not localize to focal adhesion structures in infected cells and the host bacteria were attenuated in virulence (19). In another example, YopH inhibited the activation of T lymphocytes by dephosphorylating the Lck tyrosine kinase at Tyr-394 (20), and furthermore, induced mitochondrially-dependent apoptosis of T cells (21). However, as there is no direct in vivo evidence for dephosphorylation of critical host proteins by YopH, the true cellular targets are uncertain. Therefore, we selected a synthetic peptide that contained a phosphorylated tyrosine (pTyr) residue as the substrate to be used for assay development. Measuring phosphate release by YopH, we first screened a synthetic library containing approximately 300 individual 11-mer peptides comprised of phosphorylated sequences representative of known human phospho-proteins (see Figure S1 in Supporting Information). Many pTyr-containing peptides were actively dephosphorylated by YopH but there was no evidence for sequence preference. Based on these findings, and previous publications (14, 22, 23), we chose the pTyr-containing peptide DADE-pYLIPQQG, corresponding to an autophosphorylation site (Tyr992) from the EGFR (24) for our assay. Although EGFR is not known to be a natural target of YopH in vivo, the rate constant (2.23 × 107 M−1s−1) for dephosphorylation of the autophosphorylation site peptide is near the diffusion-controlled limit (22). In contrast, the catalytic activity of YopH toward the substrate pNPP is similar to free pTyr and 1300-fold lower than the pTyr-containing peptide (22). Further, crystal structures of the PTPase domain of a substrate-trapping mutant of YopH (Cys403Ser) bound to the hexapeptide DADEpYL and the wild-type enzyme bound to a non-hydrolysable analogue of the hexapeptide, Ac-DADE-F2Pmp-L-NH2 have been determined (14, 23). The crystal structures confirmed previously reported structure-activity studies (22) and revealed a second, non-catalytic, substrate-binding site on the protein surface opposite to the active site.

YopH preferentially binds to the pTyr-EGFR peptide

Interactions between peptides and YopH were first measured by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and data were processed for best fit assuming a simple 1:1 Langmuir association model for the on-rate (kon), off-rate (koff), and dissociation constant (KD) calculations. Biotinylated Tyr- and pTyr-EGFR peptides were immobilized by neutravidin capture, using a surface density of 100 RU. Reference cells were used to correct for nonspecific binding events. As depicted in Figure 1, YopH binds more favorably to the phosphorylated EGFR peptide than the non-phosphorylated EGFR peptide. This is consistent with previous observations (25) that the pTyr within the peptide is critical for substrate binding, and implies that the phosphate moiety is an important driving force in the binding of substrate. Furthermore, data from the crystal structure suggested that pTyr is also the most likely primary determinant of specificity for peptides binding to the noncatalytic substrate binding site (23). However, a low level of YopH binding to the non-phosphorylated peptide still occurred, indicating that the amino acid residues flanking the pTyr impact binding, as indeed was demonstrated in the crystal structures and structure-activity studies (14, 22, 23). The additional residues may impart some degree of specificity and therefore strengthen affinity, as the binding of the pTyr-containing peptide must be a cooperative event that involves the recognition of both pTyr and flanking structural residues (22). Yet, peptide binding and catalysis will be influenced not only by the static crystallographic interactions observed between ligand and YopH, but also by the energy required to bring the protein and peptide into bound conformations. The interaction kinetics of the phosphopeptide and YopH are shown in Figure 2. The biotinylated phosphopeptide was captured by neutravidin immobilized on the sensor-chip surface and YopH was flowed over the captured peptide. The surface was regenerated by a short injection of a mild acid to displace bound YopH. Using a 1:1 biomolecular interaction model, the on- and off-rates (averaged between three identical experiments) were 9.57 (+/− 5.7) × 103 M−1s−1 and 2.05 (+/− 0.30) × 10−2 s−1, respectively, yielding a dissociation constant (KD) of 2.1 (+/− 1.5) × 10−6 M. The KD measured by SPR is consistent with reported values for other phosphopeptide-protein interactions (26, 27) and the equilibrium dissociation constant of 10 µM calculated from NMR binding isotherms using the same hexapeptide and the N-terminus of YopH (28).

Figure 1. YopH binds preferentially to pTyr-EGFR peptide.

(A) Representative sensorgrams obtained from injections of YopH at concentrations of 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 µM over biotinylated pTyr-EGFR peptide captured on a neutravidin surface. (B) Representative sensorgrams obtained from injections of YopH at concentrations of 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 µM over biotinylated EGFR peptide captured on the neutravidin surface.

Figure 2. Interaction of YopH with pTyr-EGFR peptide.

Representative sensorgrams (colored lines) obtained from injections of YopH at concentrations of 0.05, 0.10, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 µM over biotinylated pTyr-EGFR peptide captured on a neutravidin surface. At least two duplicate YopH concentrations were injected per experiment. Black lines depict the global fit of the data to a 1:1 biomolecular interaction model (kon and koff fit separately), yielding kon = 1.62 × 104 M−1s−1 and koff = 0.018 s−1 (KD = 1.11 × 10−6 M).

Displacement of YopH binding to EGFR phosphopeptide by a small-molecule substrate

While the direct measurements of YopH binding to the pTyr-EGFR peptide suggested that docking was controlled by the pTyr residue of substrate, we further explored this relationship by using a binding competition assay with the small-molecule substrate pNPP and phenylalanine (Phe) as a control. High concentrations of pNPP completely blocked detectable binding of the substrate-trapping YopH to the pTyr-EGFR peptide (Figure 3), while Phe presented a low level of binding inhibition at the same concentrations. These results demonstrated that a small-molecule substrate, representing the minimal enzyme recognition unit, effectively displaced protein-peptide interactions.

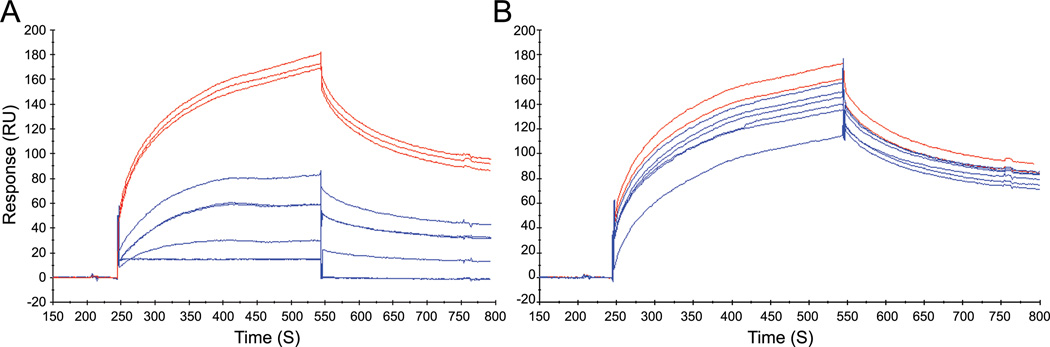

Figure 3. Competitive binding of small-molecules substrates to YopH.

Representative sensorgrams depicting inhibition of YopH (C403A/D356A) binding to the pTyr-EGFR peptide by (A) pNPP or (B) l-phenylalanine. YopH at 0.5 µM (red) was flowed over the immobilized phosphopeptide surface. A solution of inhibitor in concentrations between 1 and 50 mM was then titrated with YopH (blue) and flowed over the phosphopeptide surface. Complete recovery of YopH binding activity was confirmed after injection of inhibitors (red).

Interactions of small-molecule inhibitors with YopH

We used two SPR methods to explore interactions between YopH and the inhibitors. In one approach, the pTyr-EGFR and Tyr-EGFR peptides were immobilized onto two different flow cells and blocking of YopH binding from solution by inhibitors was assessed (Figure 4). Alternatively, wild-type-YopH and YopH C403A/D356A were immobilized onto the chip surfaces and direct binding of inhibitors from solution was observed. This second approach is similar to a method recently reported for screening libraries of PTP inhibitors (29). The small molecule inhibitors of YopH (see Figure 5) were synthesized as previously described (5) using an inhibitor platform identified through a substrate affinity approach. The lead inhibitor platform contained an amino-oxy handle used to prepare the bidentate inhibitors via oxime-based click chemistry. The IC50 values based on inhibition of YopH hydrolysis of pNPP were 3.67, 1.20, and 0.19 micromolar for compounds 1, 2, and 3, respectively (5). Table 1 compares the IC50 values based on pNPP hydrolysis and SPR measurements. The activities of compounds 1 and 2 follow the same trend as observed in the pNPP assay (5), albeit at fivefold higher values (15.8 and 6 µM, respectively). While 3 was the most potent of the inhibitors in the pNPP assay, the IC50 value of 9.5 µM by SPR using the pTyr-EGFR peptide was intermediate in ranking between the other two inhibitors (Table 1). The crystal structure of the parent amino-oxy compound in complex with YopH revealed that the inhibitors bound only to the active site (5) while a pTyr-EGFR peptide occupied both the catalytic and non-catalytic pockets (14, 23). The synthetic inhibitors did not completely block pTyr-peptide interactions with YopH, consistent with the observation that only the catalytic site is recognized. In contrast to the synthetic inhibitors, high concentrations of pNPP blocked YopH binding to the pTyr-peptide suggesting that the small-molecule substrate binds to both the catalytic and non-catalytic sites, in a manner similar to results described for pTyr (14, 23).

Figure 4. Synthetic compounds inhibit YopH binding to immobilized pTyr-EGFR peptide.

Representative sensorgrams depicting inhibition of YopH (C403A/D356A) binding to the pTyr-EGFR peptide. YopH (0.5 µM) was flowed over the immobilized phosphopeptide surface (red). A solution of inhibitor was then titrated with YopH (blue) and flowed over the phosphopeptide surface. Complete recovery of YopH binding activity was confirmed after each injection of inhibitor (red). (A–C) YopH (0.5 µM) in the presence of 1 at concentrations of 0.5, 10, and 25 µM, respectively. (D–F) YopH (0.5 µM) in the presence of 2 at concentrations of 1, 10, and 25 µM, respectively. (G–I) YopH (0.5 µM) in the presence of 3 at concentrations of 0.5, 10, and 50 µM, respectively.

Figure 5. Structures of inhibitors.

Table 1.

A comparison of IC50 values for YopH inhibitors obtained with a small molecule substrate and phosphopeptide.

| Inhibitor |

pNPP IC50 (µM) |

pTyr-EGFR peptide IC50* (µM) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.67 | 15.8 (+/− 1.6) |

| 2 | 1.2 | 6 (+/− 1.3) |

| 3 | 0.19 | 9.5 † |

Mean value +/− SEM

Estimated value

To better understand the interactions between small-molecule inhibitors and YopH, we immobilized YopH and directly measured the binding of small-molecule inhibitors or phosphopeptide. Figure 6A shows the immobilization of the catalytically inactive mutant YopH (flow cell 2) and the wild-type YopH (flow cell 4), while Figures 6B–D depict the direct binding interaction between YopH (C403A/D356A) and compounds 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The three compounds exhibited similar kinetic behavior, with on-rates of 104 (+/− 53) M−1s−1, 159 (+/− 27) M−1s−1, and 33.8 (+/− 4.7) M−1s−1, and off-rates of 1.87 (+/− 0.99) × 10−2 s−1, 2.19 (+/− 1.1) × 10−2 s−1, and 9.15 (+/− 1.5) × 10−3 s−1. While inhibitor 3 exhibited the slowest on-rate, it also exhibited the slowest off-rate, suggesting that the enzyme-inhibitor complex was more stable than complexes formed by the other inhibitors. This may explain its higher potency in the pNPP assay. The greater stability of this complex is a noteworthy feature, as inhibitors with longer residence time (koff) generally have better biological efficacy, due at least in part to increased target occupancy and fewer off-target effects (30).

Figure 6. Direct binding of synthetic inhibitors to YopH.

Representative sensorgrams depicting (A) the immobilization of YopH, and the direct binding of (B) 1 (1–50 µM), (C) 2 (1–50 µM) and (D) 3 (10–90 µM) to YopH C403A/D356A.

Table 2 compares the on- and off-rates, KD values, and free energies of interactions with immobilized YopH for the inhibitors, pTyr, and EGFR phosphopeptide. The observed KD was 134 µM for the pTyr-EGFR peptide flowed over the immobilized mutant enzyme (data not shown). This is more than a 50-fold increase to the KD value observed when the interaction partners were reversed (enzyme flowed over immobilized peptide). This is not altogether surprising, considering the likely decrease in entropy that follows when a protein is tethered to a surface, and therefore the degrees of freedom are reduced owing to the folded structure of the protein. Interactions between the pTyr-EGFR peptide and the wild-type enzyme were also examined. While it was not possible to directly monitor dephosphorylation of the peptide by SPR, the apparent KD value was 4.5-fold higher (613 µM) than observed with the mutant enzyme. The lower affinity may indicate dephosphorylation of the peptide or merely be attributable to the increased binding affinity of the substrate trapping mutant (31). Measured interactions between pTyr and the substrate trapping YopH mutant gave an apparent KD of 10 mM, which is nearly 100-fold greater than that of the phosphopeptide. As a model of protein-protein interactions that may occur in vivo, the greater affinity of PTPase for the phosphopeptide indicated a higher energy barrier for potential inhibitors to overcome compared with free pTyr. We expected a stoichiometric ratio of 1:1 for binding to immobilized peptide, and 1:2 for immobilized YopH because the EGFR peptide is able to bind to the active site as well as the second binding site of YopH. The results, however, were approximately 1:1 in both cases, perhaps due to hindered access to the second binding site from surface immobilization.

Table 2.

Kinetic interactions of substrates and inhibitors with immobilized YopH

| YopH C403A/D356A* |

YopH* |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

kon (1/Ms) |

koff (1/s) (10−2) |

KD (10−4 M) |

ΔG (kcal/ mol) |

kon (1/Ms) |

koff (1/s) (10−2) |

KD (10−4 M) |

ΔG (kcal/ mol) |

|

| pTyr-EGFR peptide | 88.8 | 1.19 | 1.34 | −5.28 | 34.9 | 2.14 | 6.13 | −4.38 |

| l-phosphotyrosine | 0.399 | 0.399 | 100 | −2.73 | 0.278 | 0.679 | 244 | −2.2 |

| 1 | 104 (53) |

1.87 (0.99) |

2.92 (3.5) |

−5.08 (0.66) |

73.4 (34.8) |

1.95 (0.95) |

3.11 (2.0) |

−4.88 (0.43) |

| 2 | 159 (27) |

2.19 (1.1) |

1.48 (1.0) |

−5.32 0.38) |

157 50) |

2.15 (0.89) |

1.41 (0.43) |

−5.28 (0.20) |

| 3 | 33.8 (4.7) |

0.915 (0.15) |

2.76 (0.8) |

−4.87 (0.18) |

44.5 (18.7) |

0.945 (0.13) |

2.39 (1.3) |

−4.39 (0.34) |

On-rates (kon), off-rates (koff), affinity constants (KD), and free energies of binding (ΔG) obtained for the various analytes and the immobilized YopH enzyme. Numbers in parentheses are the standard deviation values based on three independent experiments.

As seen in Table 2, the free energies of binding for the synthetic compounds and the phosphopeptide were more favorable than was the binding of pTyr to YopH. This observation may account for the ability of the inhibitors to reduce PTPase activity at lower concentrations in the pNPP substrate assay than in the peptide-substrate assay. Binding interactions were similar between each of the synthetic inhibitors and the inactive YopH C403A/D356A mutant or the wild-type YopH (Table 2), while the pTyr-containing substrates, which present a hydrolysable phosphate moiety, exhibited lower affinity for the wild-type YopH compared to the substrate-trapping mutant. These results were in agreement with previous studies, indicating that an increase in the enthalpy of binding (ΔH) in the general acid-deficient mutant was responsible for the apparent increased binding affinity for PTP1B and YopH substrate trapping mutants in comparison with the wild-type enzymes (31). The crystallographic structure of a difluoro-phosphonate containing (F2Pmp) analogue of the EGFR hexapeptide in complex with wild-type YopH reveals that the side chain of Asp 356 (analogous to the Asp-181 of PTP1B) rotates away from the ligand due to the presence of the fluorine atoms (14). Because the phosphate group of the substrate is replaced by a non-cleavable F2Pmp analogue in compounds 1–3, it is possible that the mutation of the negatively charged aspartic acid to the hydrophobic alanine in YopH negates this perturbation by the fluorine atoms, leading to similar affinities of the inhibitors for wild-type and mutant YopH enzymes.

A high-throughput assay based on microarrayed substrates

To confirm the compounds inhibited PTPase activity in the presence of the peptide substrate in addition to pNPP, we spotted the pTyr-EGFR peptide in microarrays on nitrocellulose-coated glass slides and incubated the surfaces with YopH pre-mixed with each of the compounds 1–3. A separate slide was spotted, processed, and scanned for each synthetic inhibitor in the same manner. Figure 7A shows a slide after treatment with the YopH-compound 1 mixture and subsequent probing with detection antibodies. Each of the 12 blocks, separated by gaskets, consisted of quadruplicate spots of antibody-conjugated Alexfluor647, for visual orientation of the block grid, and the pTyr-EGFR peptide (500 – 12.5 µM). Blocks 1 – 7 were treated with YopH pre-incubated with 1 (800, 400, 133, 44.4, 14.8, 4.9, and 1.2 µM, respectively). Block 8 was treated with YopH in 5% DMSO, while blocks 9 and 10 were treated with YopH pre-incubated with 100 µM control compounds (positive inhibitor control, 4 (11); negative inhibitor control, 5). Block 11 was treated with the catalytically inactive mutant YopH C403A/D356A, and block 12 with buffer (CBS with 5% DMSO) alone. The slide was probed with mouse anti-pTyr IgG, and bound antibody was detected with goat anti-mouse IgG antibody, conjugated with Alexafluor647. The intensity of fluorescence signals (635 nm), imaged by laser scanner, corresponded to the amount of pTyr remaining on the slide surface. The intensity of the EGFR phosphopeptide spots increased proportionally with increasing concentrations of 1 (Figure 7A), indicating a dose-response relationship. Figure 7B is a magnification of pTyr-EGFR peptide at a single concentration, with spots from block 1 from each slide (YopH pre-incubated with 800 µM inhibitor) positioned next to spots from block 8 from each slide (YopH without inhibitor), demonstrating that all three inhibitors inhibited PTPase activity. This method is well suited for high-throughput screening, and has the added advantage of being able to screen various substrates and inhibitors simultaneously. Moreover, background interference is negligible because the substrate is attached to the solid support, and all unbound material is conveniently washed away. An analogous method was examined in which the biotinylated pTyr-EGFR peptide was immobilized on streptavidin-coated paramagnetic microbeads (data not shown). Results from the microbead assay were comparable to the microarray data, suggesting that either format may be adapted to high-throughput screening for potential inhibitors.

Figure 7. A microarray assay for measuring inhibitors of PTPase activity.

(A) Dilutions of the pTyr-EGFR peptide were spotted in quadruplicate on a nitrocellulose-coated glass slide. The slide surface was incubated for 5 min with YopH and inhibitor 1 (800 – 1.2 µM, blocks 1–7), YopH only (block 8), YopH and 100 µM 4 (block 9), YopH and 100 µM 5 (block 10), YopH C403A/D356A (block 11), and buffer only (block 12). The slide was then probed with mouse anti-pTyr antibody (1 h) and detected with goat anti-mouse Alexafluor 647 antibody (1 h). The signal intensity (from white to black) directly relates to the amount of pTyr remaining on the slide after incubation with the YopH-inhibitor mixture. (B) A comparison of a single concentration of pTyr-EGFR peptide in block 1 (YopH with 800 µM of the synthetic inhibitor) and block 8 (YopH without inhibitor).

Conclusions and future directions

While enzyme active sites are important targets for inhibitor design, SPR-based screening allows for direct assessment of protein-protein interactions that influence activity in a more physiologically-relevant context. The methods that we describe can be used to obtain further information regarding on and off rates, residence time, specificity of interaction, plus affinity, and stoichiometry of binding. Additionally, the SPR approach is sensitive enough to detect the low-affinity interactions expected in compound screening because complex formation and dissociation are monitored in real time. The competition assay also provides more information about the mechanism of action, in that a competitive inhibitor will displace the analyte from the ligand, whereas an allosteric inhibitor may alter the kinetic profile of the analyte. Finally, translating the basic pTyr-peptide substrate assay into a fluorescent microarray format will facilitate high-throughput screening.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project was supported in part by an appointment of MH to the Research Participation Program for the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the USAMRMC and by funding from: the Department of Defense, Joint Science and Technology Office; federal funds from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, National Institutes of Health, under contract HHSN261200800001E; and the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Abbreviations

- CBS-P

citrate buffer saline with polysorbate-20

- CM5 chip

carboxymethyl dextran sensorchip

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- F2Pmp

difluoro-phosphonomethyl phenylalanine

- IC50

half maximal inhibitory concentration

- NHS

N-hydroxysuccinimide

- Phe

l-phenylalanine

- pNPP

para-nitrophenyl phosphate

- PTP

Protein tyrosine phosphatase

- pY or pTyr

phosphotyrosine

- RU

response or resonance unit

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- TBS-T

Tris-buffered saline with tween-20

- YopH

Yersinia pestis outer protein H

References

- 1.Hunter T. Tyrosine phosphorylation: thirty years and counting. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCain DF, Grzyska PK, Wu L, Hengge AC, Zhang ZY. Mechanistic studies of protein tyrosine phosphatases YopH and Cdc25A with m-nitrobenzyl phosphate. Biochemistry. 2004;43(25):8256–8264. doi: 10.1021/bi0496182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Z-Y. Protein-Tyrosine Phosphatases: Biological Function, Structural Characteristics, and Mechanism of Catalysis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;33(1):1–52. doi: 10.1080/10409239891204161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benyamini H, Friedler A. Using peptides to study protein-protein interactions. Future Med Chem. 2010;2(6):989–1003. doi: 10.4155/fmc.10.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahta M, Lountos GT, Dyas B, Kim S-E, Ulrich RG, Waugh DS, et al. Utilization of Nitrophenylphosphates and Oxime-Based Ligation for the Development of Nanomolar Affinity Inhibitors of the Yersinia pestis Outer Protein H (YopH) Phosphatase. J Med Chem. 2011;54(8):2933–2943. doi: 10.1021/jm200022g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang Z, He Y, Zhang X, Gunawan A, Wu L, Zhang Z-Y, et al. Derivatives of Salicylic Acid as Inhibitors of YopH in Yersinia pestis. Chem Biol Drug Design. 2010;76(2):85–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2010.00996.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee K, Gao Y, Yao Z-J, Phan J, Wu L, Liang J, et al. Tripeptide inhibitors of Yersinia protein-tyrosine phosphatase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13(15):2577–2581. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00481-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu F, Hakami RM, Dyas B, Bahta M, Lountos GT, Waugh DS, et al. A rapid oxime linker-based library approach to identification of bivalent inhibitors of the Yersinia pestis protein-tyrosine phosphatase, YopH. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20(9):2813–2816. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.03.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leone M, Barile E, Vazquez J, Mei A, Guiney D, Dahl R, et al. NMR-based design and evaluation of novel bidentate inhibitors of the protein tyrosine phosphatase YopH. Chem Biol Drug Design. 2010;76(1):10–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2010.00982.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S-E, Bahta M, Lountos GT, Ulrich RG, Burke TR, Jr, Waugh DS. Isothiazolidinone (IZD) as a phosphoryl mimetic in inhibitors of the Yersinia pestis protein tyrosine phosphatase YopH. Acta Crystallog Sect D. 2011;67(7):639–645. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911018610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang F, Huang Z, Lee S-Y, Liang J, Ivanov MI, Alonso A, et al. Aurintricarboxylic Acid Blocks in Vitro and in Vivo Activity of YopH, an Essential Virulent Factor of Yersinia pestis, the Agent of Plague. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(43):41734–41741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307152200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tautz L, Bruckner S, Sareth S, Alonso A, Bogetz J, Bottini N, et al. Inhibition of Yersinia Tyrosine Phosphatase by Furanyl Salicylate Compounds. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(10):9400–9408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patterson AW, Wood WJL, Ellman JA. Substrate activity screening (SAS): a general procedure for the preparation and screening of a fragment-based non-peptidic protease substrate library for inhibitor discovery. Nat Protocols. 2007;2(2):424–433. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phan J, Lee K, Cherry S, Tropea JE, Burke TR, Waugh DS. High-Resolution Structure of the Yersinia pestis Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase YopH in Complex with a Phosphotyrosyl Mimetic-Containing Hexapeptide. Biochemistry. 2003;42(45):13113–13121. doi: 10.1021/bi030156m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang ZY, Clemens JC, Schubert HL, Stuckey JA, Fischer MW, Hume DM, et al. Expression, purification, and physicochemical characterization of a recombinant Yersinia protein tyrosine phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(33):23759–23766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y-L, Keng Y-F, Zhao Y, Wu L, Zhang Z-Y. Suramin Is an Active Site-directed, Reversible, and Tight-binding Inhibitor of Protein-tyrosine Phosphatases. The J Biol Chem. 1998;273(20):12281–12287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flint AJ, Tiganis T, Barford D, Tonks NK. Development of “substrate-trapping” mutants to identify physiological substrates of protein tyrosine phosphatases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(5):1680–1685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith CL, Khandelwal P, Keliikuli K, Zuiderweg ERP, Saper MA. Structure of the type III secretion and substrate-binding domain of Yersinia YopH phosphatase. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42(4):967–979. doi: 10.1046/j.0950-382x.2001.02711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deleuil F, Mogemark L, Francis MS, Wolf-Watz H, Fällman M. Interaction between the Yersinia protein tyrosine phosphatase YopH and eukaryotic Cas/Fyb is an important virulence mechanism. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5(1):53–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alonso A, Bottini N, Bruckner S, Rahmouni S, Williams S, Schoenberger SP, et al. Lck Dephosphorylation at Tyr-394 and Inhibition of T Cell Antigen Receptor Signaling by Yersinia Phosphatase YopH. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(6):4922–4928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308978200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruckner S, Rhamouni S, Tautz L, Denault J-B, Alonso A, Becattini B, et al. Yersinia Phosphatase Induces Mitochondrially Dependent Apoptosis of T Cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(11):10388–10394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408829200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang ZY, Maclean D, McNamara DJ, Sawyer TK, Dixon JE. Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Substrate Specificity: Size and Phosphotyrosine Positioning Requirements in Peptide Substrates. Biochemistry. 1994;33(8):2285–2290. doi: 10.1021/bi00174a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ivanov MI, Stuckey JA, Schubert HL, Saper MA, Bliska JB. Two substrate-targeting sites in the Yersinia protein tyrosine phosphatase co-operate to promote bacterial virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55(5):1346–1356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rotin D, Margolis B, Mohammadi M, Daly RJ, Daum G, Li N, et al. SH2 domains prevent tyrosine dephosphorylation of the EGF receptor: identification of Tyr992 as the high-affinity binding site for SH2 domains of phospholipase C gamma. The EMBO J. 1992;11(2):559–567. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang ZY, Maclean D, Thiemesefler AM, Roeske RW, Dixon JE. A Continuous Spectrophotometric and Fluorometric Assay for Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Using Phosphotyrosine-Containing Peptides. Anal Biochem. 1993;211(1):7–15. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ladbury JE, Lemmon MA, Zhou M, Green J, Botfield MC, Schlessinger J. Measurement of the binding of tyrosyl phosphopeptides to SH2 domains: a reappraisal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(8):3199–3203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beebe KD, Wang P, Arabaci G, Pei D. Determination of the Binding Specificity of the SH2 Domains of Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase SHP-1 through the Screening of a Combinatorial Phosphotyrosyl Peptide Library. Biochemistry. 2000;39(43):13251–13260. doi: 10.1021/bi0014397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khandelwal P, Keliikuli K, Smith CL, Saper MA, Zuiderweg ERP. Solution Structure and Phosphopeptide Binding to the N-terminal Domain of Yersinia YopH: Comparison with a Crystal Structure. Biochemistry. 2002;41(38):11425–11437. doi: 10.1021/bi026333l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeder-Lutz G, Choulier L, Besse M, Cousido-Siah A, Figueras FXR, Didier B, et al. Validation of surface plasmon resonance screening of a diverse chemical library for the discovery of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1b binders. Anal Biochem. 2012;421(2):417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu H, Tonge PJ. Drug–target residence time: critical information for lead optimization. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14(4):467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.06.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y-L, Yao Z-J, Sarmiento M, Wu L, Burke TR, Jr, Zhang Z-Y. Thermodynamic Study of Ligand Binding to Protein-tyrosine Phosphatase 1B and Its Substrate-trapping Mutants. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(44):34205–34212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.