Abstract

Central to evaluating the effects of ocean acidification (OA) on coral reefs is understanding how calcification is affected by the dissolution of CO2 in sea water, which causes declines in carbonate ion concentration [CO32−] and increases in bicarbonate ion concentration [HCO3−]. To address this topic, we manipulated [CO32−] and [HCO3−] to test the effects on calcification of the coral Porites rus and the alga Hydrolithon onkodes, measured from the start to the end of a 15-day incubation, as well as in the day and night. [CO32−] played a significant role in light and dark calcification of P. rus, whereas [HCO3−] mainly affected calcification in the light. Both [CO32−] and [HCO3−] had a significant effect on the calcification of H. onkodes, but the strongest relationship was found with [CO32−]. Our results show that the negative effect of declining [CO32−] on the calcification of corals and algae can be partly mitigated by the use of HCO3− for calcification and perhaps photosynthesis. These results add empirical support to two conceptual models that can form a template for further research to account for the calcification response of corals and crustose coralline algae to OA.

Keywords: coral reef, calcification, bicarbonate, carbonate

1. Introduction

The calcium carbonate framework produced by coral reefs extends over large areas and hosts the highest known marine biodiversity [1]. In addition to the emblematic scleractinian corals, calcifying taxa such as crustose coralline algae (CCA) play key roles in the function of reefs by cementing components of the substratum together and providing cues for coral settlement [2]. Over the past century, however, coral reefs have been impacted by a diversity of disturbances [3] and now are threatened by ocean acidification (OA). This phenomenon is caused by the dissolution of atmospheric CO2 in sea water, which reduces pH, depresses carbonate ion concentration [CO32−] and increases bicarbonate ion concentration [HCO3−] and aqueous CO2 [4]. As a result, most experimental studies of the effects of OA on the calcification of marine taxa have reported negative effects [5].

The threats of OA are well publicized for coral reefs [6], where there is concern that this ecosystem might cease to form calcified structures within 100 years [7]. This trend places corals and CCA at the centre of the debate regarding the magnitude of the effects of OA on tropical reefs, but a poor understanding of the calcification mechanisms involved has impaired progress in this debate. Even the fundamental question regarding the source of inorganic carbon favoured for mineralization by corals and algae remains unanswered [8,9]. Evaluating the roles of CO32− and HCO3− in supplying dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) for calcification by corals and CCA poses a significant challenge to progress in this field of investigation, notably in terms of describing calcification mechanisms upon which further studies of OA can be based, and determining the response of tropical reefs to OA. Critically, if calcifying taxa can use HCO3− directly to support the DIC needs of calcification [10] or indirectly by converting HCO3− to CO32− at the calcification site [11], there is the potential for OA to stimulate calcification in contrast to the frequently described trend of calcification impairment through declines in CO32−. This possibility has important implications, not least of which is the capacity to reconcile inconsistent results originating from experiments in which corals have been exposed to OA. Results of experiments simulating the effects of OA on calcifying taxa vary greatly, with a few revealing positive [10,12] or null effects [13] of rising partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2), and many revealing negative effects including as much as an 85 per cent reduction in calcification when pCO2 doubles [14]. Here, we present results from a manipulative experiment designed to test the roles of HCO3− and CO32− on calcification of the coral Porites rus and the CCA Hydrolithon onkodes in the light and dark. Based on our results and existing theory [8,15], we synthesize conceptual models of calcification mechanisms for corals and CCA that can account for the differential effects of OA on these organisms and provide a framework for future mechanistic studies of calcification.

2. Material and methods

(a). Mesocosm and carbonate chemistry manipulation

This study was conducted during July 2011 in Moorea, French Polynesia, using branches (4 cm long) of P. rus and cores (4 cm diameter) of H. onkodes collected from the back reef (2–3 m depth). Specimens were transported to the Richard B. Gump South Pacific Research Station and glued (Z-Spar A788 epoxy) to 5 × 5 cm plastic racks to create nubbins (n = 108 per taxon). Before experimental incubations began, nubbins were maintained for 3 days in a sea-table with a high flow of sea water freshly pumped from Cook's Bay to allow for recovery.

Six nubbins of coral and six cores of CCA were placed in each of nine, 150 l tanks in a 12-tank mesocosm filled with unfiltered sea water pumped from Cook's Bay. Temperature in the tanks was maintained at 27.3 ± 0.3°C (mean ± s.d., n = 252), and tanks were illuminated with LED lamps (75 W, Sol LED Module, Aquaillumination) on a 12 L : 12 D cycle providing approximately 700 ± 75 μmol photons m−2 s−1 of photosynthetically active radiation (measured below the sea water surface with a 4π quantum sensor LI-193 and a LiCor LI-1400 m). Water motion in the tanks was created with pumps (Rio 8HF, 2080 l h−1).

Carbonate chemistry was manipulated using combinations of CO2-equilibrated air, 1 M HCl (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA), 1 M NaOH (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and Na2CO3 (EMD, Gibbstown, NJ, USA; electronic supplementary material, table S1). CO2 treatments were created by bubbling ambient air, CO2-enriched air or CO2-depleted air into the tanks. CO2-enriched air was created with a solenoid-controlled gas regulation system (model A352, Qubit Systems) that mixed pure CO2 and ambient air at the desired values. CO2-depleted air was obtained by scrubbing CO2 from ambient air passing through a soda lime column. The flow of air and CO2-manipulated air was delivered continuously in each tank and adjusted independently by needle valves, with adjustments conducted twice daily following pH measurements. The manual adjustments of the needle valves were used to ensure that the actual tank pH (see below) was close to target values. Half of the sea water in each tank was changed every second day with fresh sea water pre-equilibrated at the targeted CO2 and DIC values. pH of the sea water was monitored twice daily, and sea water samples collected for total alkalinity (AT) measurements (see §2b). The experiment ran for two weeks, and was conducted in two trials that began 2 days apart, with each using new nubbins of coral and cores of CCA.

(b). Carbonate chemistry

Sea water pH was measured twice daily (08.00 and 18.00 h) in each tank, using a pH meter (Orion, 3-stars mobile) or an automatic titrator (T50, Mettler-Toledo) calibrated every 2–3 days on the total scale using Tris/HCl buffers (Dickson, San Diego, CA, USA) with a salinity of 34.5. AT of the sea water in the tanks was measured every 2 days following water changes, using single samples drawn from each tank in glass-stoppered bottles (250 ml). Samples were analysed for AT within 1 day using open cell, potentiometric titration and an automatic titrator (T50, Mettler-Toledo). Titrations were conducted on 50 ml samples at approximately 24°C, and AT calculated as described by Dickson et al. [16]. Titrations of certified reference materials provided by A. G. Dickson (batch 105) yielded AT values within 4.0 µmol kg−1 of the nominal value (s.d. = 4.1 µmol kg−1; n = 12). Salinity in the experimental tanks was measured every 2 days using a conductivity meter (YSI 3100). AT, pHT, temperature and salinity were used to calculate [HCO3−] and [CO32−] using the seacarb package [17] running in R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

(c). Mean calcification

Calcification was measured using two techniques: buoyant weight [18] was used to evaluate the importance of [HCO3−] and [CO32−] to calcification over two weeks, and the alkalinity anomaly technique [19] was used to differentiate short-term (approx. 1 h) calcification in the light and dark in response to variable [HCO3−] and [CO32−]. Buoyant weight (±1 mg) was recorded before and after the 15 days of incubation, and the difference between the two was converted to dry weight using an aragonite density of 2.93 g cm−3 for P. rus, and a calcite density of 2.71 g cm−3 for H. onkodes. Calcification was normalized to surface area estimated using aluminium foil for P. rus, and by digital photography and image analysis (ImageJ, NIH US Department of Health and Human Services) for H. onkodes.

(d). Light versus dark calcification

Light and dark calcification were estimated, using the alkalinity anomaly technique. One coral and one piece of CCA from each treatment were chosen randomly at 12.00 h on days 5 and 7 of the incubation, and placed in separate 500 ml glass beakers containing 320 ml of sea water from the respective incubation tanks. Incubations lasted 1 h at conditions that were the same as those in the 150 l incubation tanks (27°C, light intensity approx. 700 μmol photons m−2 s−1). Small pumps (115 l h−1) circulated sea water in the beakers. To monitor pCO2 and ensure that [HCO3−] and [CO32−] remain constant throughout the incubation, pH was controlled using a pH meter (Orion, 3-stars mobile) every 20 min during the incubation and adjusted when it deviated approximately 0.05 from the respective treatments by addition of pure CO2 or CO2-free air. As the incubations lasted 1 h, we assumed that the variation in AT (measured before and at the end of the incubation) was owing to calcification/dissolution, and used the stoichiometric relation of two moles AT being removed for each one mole of CaCO3 precipitated to calculate calcification [19]. On the same day (days 5 and 7 of the incubation) and in darkness 2–5 h after sunset at 17.30 h, calcification in the dark was measured using an identical procedure.

(e). Statistical analyses

For the analysis of calcification by buoyant weight, a three-way model I ANOVA was used to test the effects of trial, [CO32−] and [HCO3−] (see the electronic supplementary material, table S2). While the significance of all effects was evaluated against a preset α of 0.05, a more conservative criterion of p > 0.25 [20] was used as a basis to drop the trial effect from the statistical model. Trial was not significant for P. rus (p > 0.25) [20] and it therefore was dropped from the model and the analysis repeated as a two-way model I ANOVA (see the electronic supplementary material, table S3). The trial effect was significant for H. onkodes (p < 0.001), but the directions of the treatment effects were similar in both trials and only the magnitude differed. For this reason, we also dropped the trial effect for H. onkodes and repeated the analysis as a two-way model I ANOVA (see the electronic supplementary material, table S3).

For the analysis of calcification by the alkalinity anomaly method, a three-way model I ANOVA was used to test independently in the light and dark the effect of trial, [CO32−] and [HCO3−] (see the electronic supplementary material, tables S4 and S5). An effect of trial was detected for H. onkodes dark calcification (p = 0.156) but was considered not biologically meaningful, because the direction of the effect was similar between trials.

All analyses were conducted separately by taxon, and the assumptions of normality and equality of variance were evaluated through graphical analyses of residuals. All analyses were performed, using the software R. Data were deposited in the Biological and Chemical Oceanography Data System (http://osprey.bco-dmo.org/project.cfm?flag=view&id=265&sortby=project).

3. Results

(a). Carbonate chemistry manipulations

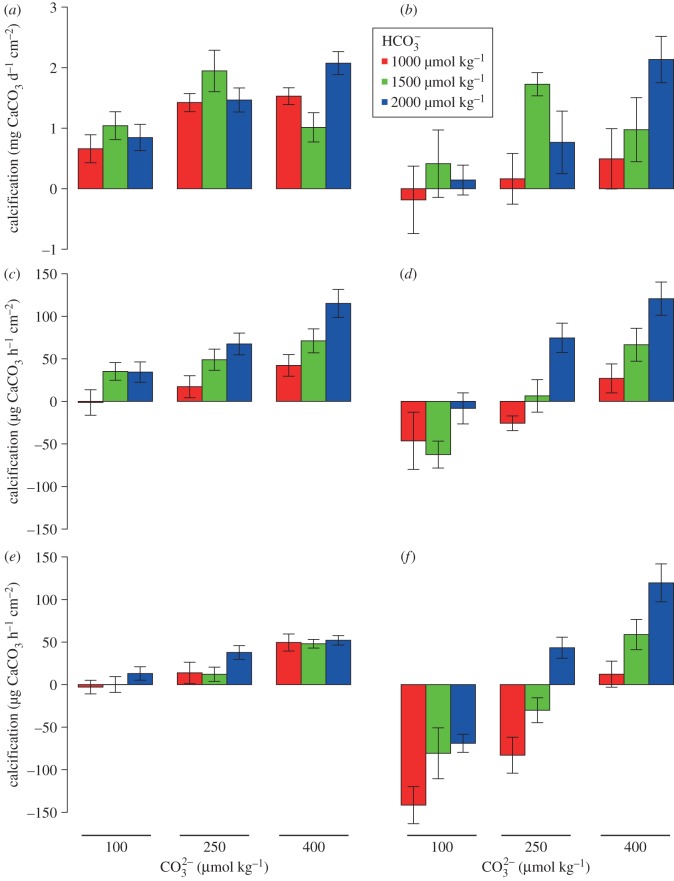

Our approach to manipulating the carbonate chemistry of treatment sea water yielded precise and replicable results creating nine treatments (see figure 1 and electronic supplementary material, table S6). The treatments extended the range of conditions used commonly in OA perturbation experiments (i.e. from pre-industrial pCO2 to the conditions expected by the end of the current century; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean carbonate [CO32−] and bicarbonate [HCO3−] ion concentrations in nine treatments over two, two-week incubations. The horizontal and vertical error bars represent the s.e.m. of the [CO32−] and [HCO3−], respectively (n = 45); the central point corresponds to the control (present-day values). The red star represents [CO32−] and [HCO3−] expected in 2100 (27°C, pCO2 approx. 800 μ atm, AT = 2300 μmol kg−1), and the blue star is an estimate of pre-industrial [CO32−] and [HCO3−](27°C, pCO2 approx. 280 μatm, AT = 2300 μmol kg−1).

(b). Mean calcification

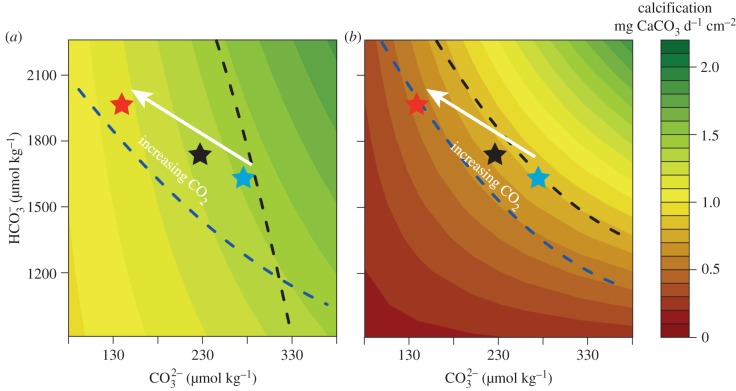

For P. rus, calcification was associated positively with [CO32−] (p < 0.001), but not [HCO3−] (p = 0.368), and was affected by the statistical interaction between [CO32−] and [HCO3−] (p = 0.009; electronic supplementary material, table S3; figure 2a). The maximum rate of calcification (2.07 ± 0.21 mg CaCO3 d−1 cm−2) occurred at high concentrations of both [CO32−] and [HCO3−], and the lowest (0.66 ± 0.14 mg CaCO3 d−1 cm−2) under low [CO32−] and [HCO3−] (figure 2a). Porites rus deposited CaCO3 under conditions in which external inorganic carbon was reduced (i.e. low [CO32−] and [HCO3−]).

Figure 2.

Calcification rates of Porites rus (left column) and Hydrolithon onkodes (right column) as a function of [CO32−] and [HCO3−]. (a,b) Net calcification measured by buoyant weight over two, two-week incubations; (c,d) net calcification in the light measured by the alkalinity anomaly technique; and (e,f) calcification in the dark measured by the alkalinity anomaly technique. Each group of bars corresponds to three [CO32−] (approx. 100, 250 and 400 μmol kg−1); colours of bars are dependent on [HCO3−] (red approx. 1000, green approx. 1500, and blue approx. 2200 μmol kg−1). All values are mean ± s.e.m. (n = 12 for buoyant weight and n = 4 for the light and dark calcification).

For H. onkodes, calcification was affected by [CO32−] (p = 0.014) and [HCO3−] (p = 0.019), but not by the interaction between the two (p = 0.161; electronic supplementary material, table S3; figure 2). Similar to P. rus, mean calcification of H. onkodes was highest (2.13 ± 0.25 mg CaCO3 d−1 cm−2) when both [CO32−] and [HCO3−] were elevated, and lowest (−0.18 ± 0.49 mg CaCO3 d−1 cm−2) when both [CO32−] and [HCO3−] were depressed (figure 2b). In contrast to P. rus, however, net dissolution occurred under the lowest concentrations of [CO32−] and [HCO3−], demonstrating that dissolution exceeded precipitation of CaCO3.

(c). Light versus dark calcification

In both P. rus and H. onkodes, calcification was higher in the light than in the dark. In contrast to calcification over both light and dark cycles as measured by changes in buoyant weight, calcification in the light for P. rus was affected by [CO32−] (p < 0.001) and [HCO3−] (p < 0.001; figure 2c; electronic supplementary material, table S4). In the dark, calcification was affected strongly by [CO32−] (p < 0.001), but not by [HCO3−] (p = 0.078; figure 2e; electronic supplementary material, table S4).

For H. onkodes, light and dark calcification were affected by [CO32−] (p < 0.001) and [HCO3−] (p < 0.001; figure 2d,f and electronic supplementary material, table S5) in a pattern similar to that recorded for calcification over the whole experiment. Calcification in the light and dark was similar in high [CO32−], whereas dark calcification was more negatively affected than light calcification by decreasing [CO32−]. In the low [CO32−] treatments, net calcification became negative with dissolution exceeding calcification.

4. Discussion

(a). Empirical data

The results from our analysis contrast to previous findings [21–25] as we show that both [HCO3−] and [CO32−] positively affect calcification in a tropical coral during a two-week incubation. Critically however, our experiment yields results that can reconcile these differences through mechanisms that are experimentally testable. Some previous studies suggest that coral calcification is governed by [HCO3−] and not [CO32−] [21,22], but these earlier studies were limited to an analysis of calcification in the light, as measured using the alkalinity anomaly technique [21], or did not distinguish the differential effects on calcification of [HCO3−] and [CO32−], two parameters of DIC chemistry in sea water that covary [22]. The conclusions of these studies are partly in agreement with our results, because [HCO3−] played an important role in coral calcification in the light. By contrast, most previous experimental studies [23–25], and the review articles [14,26], suggest that coral calcification is controlled by the saturation state of aragonite (Ωa), and the concentration of CO32− from which it is derived. We propose that dependency on Ωa and [CO32−] is also in agreement with our study, because we demonstrate that mean calcification of P. rus was related to [CO32−]. It is important to note however that our pCO2 treatments would also have resulted in slight changes in aqueous CO2 that ranges from 3 to 56 μmol kg−1 (see the electronic supplementary material, table S6). It is possible that this influenced the experimental outcome (e.g. the functional relationships between calcification and both CO32− and HCO3−), as it is suggested to do with photosynthetic carbon fixation in the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi [27]. While we cannot exclude this possibility in our system, we suspect that aqueous CO2 did not play an important role in affecting calcification, because elevated rates of calcification were measured in the high [CO32−] treatment where aqueous CO2 was low (between 3 and 11 μmol kg−1; electronic supplementary material, table S6). To rigorously test for an effect of aqueous CO2 on the calcification of corals and CCA, an experimental design differing from the one used here would be required. The separation of HCO3− and CO2aq could notably be obtained by increasing pCO2 to increase aqueous CO2 and by adding HCl to maintain [HCO3−] low. However, such manipulation of the carbonate chemistry would induce working at very low pH, far from realistic values.

As our results indicate that the use of HCO3− by corals for calcification is linked to light intensity, it is intriguing to speculate that this phenomenon is related functionally to other light-dependent process, notably light-enhanced calcification [28] and photosynthesis. Photosynthesis in corals has long been hypothesized to be coupled directly with calcification [24], and can (under some conditions) be stimulated through HCO3− additions [22]. Based on these observations as well as our results, we hypothesize that there is a light-dependent increase in the importance of [HCO3−] for coral calcification, and further, that saturation of this relationship is reached at a high irradiance, when the maximum photosynthetic rate is reached.

In CCA, calcification has received less attention than in corals. The few studies investigating the response of CCA to modified carbonate chemistry conclude that calcification declines when [CO32−] diminishes [29–31] or displays a parabolic response to decreasing [CO32−] [11]. By contrast, the response of photosynthesis of CCA to [HCO3−] is controversial [30,32]. It is possible however that both calcification and photosynthesis in CCA presently are limited by DIC [11,31], which is consistent with our study where calcification was dependent on both [HCO3−] and [CO32−] in the light and dark. Critically, DIC limitation suggests CCA may be somewhat more resistant to the effects of OA than other organisms because they would be able to use increases in [HCO3−] caused by the dissolution of CO2 in sea water. For CCA, the magnitude of this effect presumably overcomes the negative implications of depositing an unusually soluble form of CaCO3 (i.e. high-magnesium calcite). Nevertheless, our results, as well as previous studies [33–35, but see 11], suggest that although coralline algae can use HCO3− to calcify, it is not sufficient to compensate for the decrease in [CO32−] that occurs with OA. As a result, net calcification is nullified or becomes negative as a result of dissolution under low [CO32−] [35].

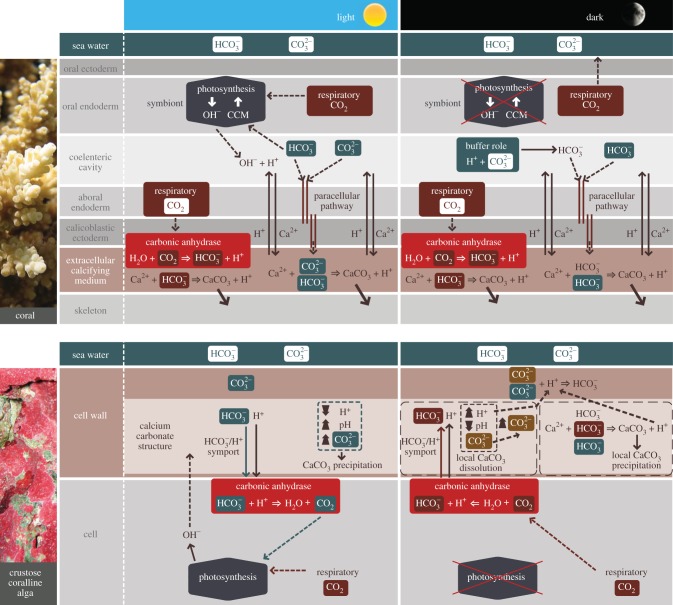

Our results have the potential to explain a portion of the high variance in responses described in experiments in which the calcification of corals and CCA has been measured under OA conditions [6,14]. The disparate results in previous experiments may originate, in part, from the choice of taxa for study that vary in their capacity to support calcification through the use of [HCO3−] and/or [CO32−], which is mediated by their capacity to tightly control pH at the calcification site [15]. Calcifying taxa such as P. rus and H. onkodes that are able to use HCO3− for calcification may be less affected by OA than taxa that are more dependent on CO32−. To test this hypothesis, we performed a linear interpolation of our results to estimate the mean calcification rate of both P. rus and H. onkodes under the range of [HCO3−] and [CO32−] used during this experiment to evaluate the potential for increases in [HCO3−] from OA to compensate for the decrease in [CO32−] (figure 3). The results of this interpolation suggest that in the light, corals can sustain present-day calcification if the decrease in [CO32−] is compensated for by an increase in [HCO3−] (figure 3a, blue dashed line). However, to maintain present-day rates of light calcification through to the end of the current century, the necessary increase in [HCO3−] (approx. 15%) is slightly greater than the effect anticipated (approx. 10%) from OA modelled under the representative concentration pathway scenario 6.0. By contrast, increasing [HCO3−] when [CO32−] is decreased is not sufficient to maintain dark calcification at present-day rates (figure 3a, black dashed line). Unlike P. rus, for H. onkodes when [CO32−] decreases owing to rising pCO2, light and dark calcification can be maintained at the present-day value only when there is an increase in [HCO3−] beyond that caused simply by the effects of OA on the equilibrium reactions controlling DIC in sea water (figure 3b). Our hypothesis suggests that the negative effect of declining [CO32−] on the calcification of corals and calcified algae can be partially mitigated by the use of HCO3− to support calcification, particularly in the light.

Figure 3.

Estimated calcification of (a) Porites rus and (b) Hydrolithon onkodes as a function of past, present, and future [CO32−] and [HCO3−]; the colour of the background represents rates of calcification. The black star shows the position of the present [CO32−] and [HCO3−]; blue and red stars are predicted estimates of these concentrations in the years 1800 and 2100, respectively. The dashed lines represent the theoretical [CO32−] and [HCO3−] necessary to sustain a calcification rate at a level equivalent to the control in the dark (black line) and light (blue line).

(b). Conceptual models of calcification

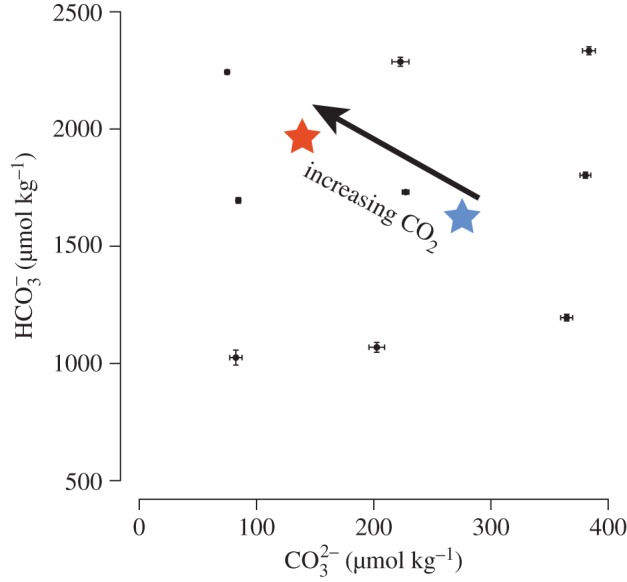

Understanding the mechanism(s) of calcification in corals and algae is critical to assess the impact of global climate change on reefs. Building from our results and previous theoretical work [8,15], we synthesize two conceptual models to describe the mechanisms of calcification in the light and dark in corals and CCA (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Conceptual models of calcification mechanisms in coral and CCA in the light and dark. The first and second rows are respectively schematic of a cross section of coral tissue and a cross section of a CCA cell. The ions with a green background correspond to ions originating from the external environment; the ions with a brown background are from internal carbon (i.e. respiratory CO2). Dashed arrows correspond to diffusion and solid arrows to active transport. For corals, under light conditions, increasing [CO32−] has a stimulatory effect on calcification, and increasing [HCO3−] has a stimulatory effect on calcification as well as photosynthesis and calcification. In dark conditions, [CO32−] play a central role by buffering the H+ released in the coelenteric cavity that allows maintaining a relatively high pH at the calcification site. In CCA, under light conditions, [CO32−] has a direct stimulatory effect on calcification, whereas [HCO3−] has a stimulatory effect on photosynthesis, which in turn stimulates calcification indirectly. In the dark, both [HCO3−] and [CO32−] are involved in calcification, but [CO32−] plays a central role by buffering the excess of H+. A detailed description of the mechanisms is presented in §4.

For corals in the light, that HCO3− is involved in calcification and photosynthesis, whereas CO32− is used only in calcification. Inorganic carbon at the calcification site is supplied by HCO3− and CO32− possibly delivered from the external environment by paracellular pathways [36], and by the transformation of metabolic CO2 into HCO3−, which can be catalysed by the enzyme carbonic anhydrase. The transformation of HCO3− into CO2 for photosynthesis results in the production of hydroxyl ions (OH−) [37], which chemically buffer protons (H+) released in the gastrovascular cavity by H+/Ca2+ ion exchangers that help transport Ca2+ to, and remove H+ from, the extracellular calcifying medium [38]. Because of the exchanges of these ions, potentially promoted by metabolic energy derived from photosynthetically fixed carbon, corals are able to maintain a high pH within the extracellular calcifying medium beneath the calicoblastic ectoderm (pH = 8.6–10) [15,39,40]. This high pH increases Ωa favouring the precipitation of calcium carbonate in the presence of an organic matrix, which is believed to play a role as a template modulating calcium carbonate precipitation [41]. In this model, increasing [CO32−] has a stimulatory effect on calcification, and increasing [HCO3−] has a stimulatory effect on calcification as well as photosynthesis, which in turn stimulates calcification.

In the dark, because OH− ions from photosynthesis are absent, CO32− buffers H+ and is transformed in the gastrovascular cavity mostly into HCO3−, which then is transferred to the extracellular calcification medium. In this model, relatively high pH at the calcification site (pH approx. 8.4) [40] and the flux of protons from the extracellular calcifying medium to the gastrovascular cavity normally is favoured by the buffering capacity of CO32−. However, when [CO32−] decreases, as under OA conditions, the transfer of H+ away from the extracellular calcifying medium is reduced, causing H+ to accumulate in the extracellular calcifying medium. As a result, pH as well as Ωa is depressed, thereby slowing rates of precipitation of CaCO3.

Calcification in CCA differs from corals as it takes place within the cell wall of the thallus [42]. In the light, HCO3− and H+ are transported into the cell by HCO3−/H+ symports [42], where they are transformed into CO2 and H2O by carbonic anhydrase. The supply of CO2 for photosynthesis is provided by the HCO3− transformed into CO2, and by the direct use of respiratory CO2 (rather than HCO3− by Symbiodinium) [42]. Photosynthesis induces the releases of OH− that diffuse into the cell wall where they cause a further increase in pH favouring increased [CO32−] and increased Ωc that facilitate precipitation of CaCO3. In this model, increasing [CO32−] has a direct stimulatory effect on calcification, whereas increasing [HCO3−] has a stimulatory effect on photosynthesis, which in turn stimulates calcification indirectly.

We hypothesize for CCA in the dark that carbonic anhydrase catalyses the hydration of respiratory CO2 to HCO3− and H+ that are transferred from within the cell to the cell wall, where H+ are buffered by CO32− to form HCO3−. Inorganic carbon is supplied in the alkaline region of the cell wall from three sources: (i) the transformation of respiratory CO2 into HCO3−, (ii) HCO3− from external sea water, and (iii) from the ions released by dissolution of the skeleton. As in the light, both [HCO3−] and [CO32−] are involved in dark calcification, but [CO32−] plays a central role by buffering the release of H+ and limiting CaCO3 dissolution.

Together, our results suggest that the response of tropical coral reef communities to OA might be less dramatic than predicted previously [7]. However, it is important to note that our results originate in experiments involving 15-day incubation of organisms under experimental [HCO3−] and [CO32−], and we do not know the extent to which these results would be replicated over ecologically relevant durations that arguably should be months to years. The capacity of research facilities in the tropics to conduct such experiments currently is inadequate; for example of the 33 perturbation experiments compiled by Erez et al. [14], 21 lasted less than or equal to two weeks and 12 lasted more than two weeks. There is some evidence that at least corals might be able to acclimatize to longer exposures to high pCO2 [43], which might be caused by modulating the ability to use HCO3−. Furthermore, it is possible that the capacity to use HCO3− is accentuated during longer-term exposure as appears to be the case in the cold water coral Lophelia pertusa. In this coral, calcification was reduced by OA during short incubations (8 days) but was unaffected during long-term incubations (six months) [12]. Further, our study lends support to the emerging consensus that the response of calcified taxa to OA will be heterogeneous [44,45] and perhaps dependent on the capacity of organisms to use HCO3− to calcify. Nevertheless, despite the ability of corals and CCA to use HCO3− in the light, the decrease in dark calcification and/or dissolution under dark or low light conditions undoubtedly will lead to an overall reduction in the calcification of coral reefs in a future characterized by a more acidic ocean.

Acknowledgements

We thank NSF for financial support (OCE no. 10-41270) and the Moorea coral reef long-term ecological research site (OCE no. 04-17413 and 10-26852) for logistic support. N. Spindel provided critical laboratory assistance, and B. O'Conner provided valuable graphical skills for figure 4. Thanks are also due to J. Ries and the anonymous reviewer for useful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. This is contribution 189 of the California State University, Northridge, Marine Biology Programme.

References

- 1.Moberg F, Folke C. 1999. Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecol. Econ. 29, 215–233 10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00009-9 (doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00009-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heyward AJ, Negri AP. 1999. Natural inducers for coral larval metamorphosis. Coral Reefs 18, 273–279 10.1007/s003380050193 (doi:10.1007/s003380050193) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes TP, et al. 2003. Climate change, human impacts, and the resilience of coral reefs. Science 301, 929–933 10.1126/science.1085046 (doi:10.1126/science.1085046) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feely RA, Sabine CL, Lee K, Berelson W, Kleypas J, Fabry VJ, Millero FJ. 2004. Impact of anthropogenic CO2 on the CaCO3 system in the oceans. Science 305, 362–366 10.1126/science.1097329 (doi:10.1126/science.1097329) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gattuso J-P, Bijma J, Gelhen M, Riebesell U, Turley C. 2011. Ocean acidification: knowns, unknowns, and perspectives. In Ocean acidification (eds Gattuso J-P, Hansson L.), pp. 291–311 Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleypas J, Yates K. 2009. Coral reefs and ocean acidification. Oceanography 22, 108–117 10.5670/oceanog.2009.101 (doi:10.5670/oceanog.2009.101) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoegh-Guldberg O, et al. 2007. Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science 318, 1737–1742 10.1126/science.1152509 (doi:10.1126/science.1152509) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tambutté S, Holcomb M, Ferrier-Pagès C, Reynaud S, Tambutté É, Zoccola D, Allemand D. 2011. Coral biomineralization: from the gene to the environment. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 408, 58–78 10.1016/j.jembe.2011.07.026 (doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2011.07.026) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gattuso J-P, Riebesell U. 2011. Reconciling apparently contradictory observations. In Workshop report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change workshop on impacts of ocean acidification on marine biology and ecosystems (eds Field CB, et al.), pp. 10–16 Stanford, CA: IPCC Working Group II Technical Support Unit [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iglesias-Rodriguez DM, et al. 2008. Phytoplankton calcification in a high-CO2 world. Science 320, 336–340 10.1126/science.1154122 (doi:10.1126/science.1154122) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ries JB, Cohen AL, McCorkle DC. 2009. Marine calcifiers exhibit mixed responses to CO2-induced ocean acidification. Geology 37, 1131–1134 10.1016/j.gca.2011.04.025 (doi:10.1016/j.gca.2011.04.025) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Form AU, Riebesell U. 2012. Acclimation to ocean acidification during long-term CO2 exposure in the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 843–853 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02583.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02583.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodolfo-Metalpa R, et al. 2011. Coral and mollusc resistance to ocean acidification adversely affected by warming. Nat. Clim. Change 1, 308–312 10.1038/nclimate1200 (doi:10.1038/nclimate1200) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erez J, Reynaud S, Silverman J, Schneider K, Allemand D. 2011. Coral calcification under ocean acidification and global change. In Coral reefs: an ecosystem in transition (eds Dubinsky Z, Stambler N.), pp. 151–176 Berlin, Germany: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ries JB. 2011. A physicochemical framework for interpreting the biological calcification response to CO2-induced ocean acidification. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 4053–4064 10.1016/j.gca.2011.04.025 (doi:10.1016/j.gca.2011.04.025) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickson AG, Sabine CL, Christian JR. 2007. Guide to best practices for ocean CO2 measurements, vol. 3. Canada: PICES Special Publication [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavigne H, Gattuso J-P.2011. Seacarb: seawater carbonate chemistry with R, R package version 2.4.1. See http://CRAN.Rproject.org/package=seacarb .

- 18.Davies PS. 1989. Short-term growth measurements of corals using an accurate buoyant weighing technique. Mar. Biol. 101, 389–395 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chisholm JRM, Gattuso J-P. 1991. Validation of the alkalinity anomaly technique for investigating calcification and photosynthesis in coral reef communities. Limnol. Oceanogr. 36, 1232–1239 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quinn GP, Keough MJ. 2002. Experimental design and data analysis for biologists. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jury CP, Whitehead RF, Szmant AM. 2010. Effects of variations in carbonate chemistry on the calcification rates of Madracis auretenra (=Madracis mirabilis sensu Wells, 1973): bicarbonate concentrations best predict calcification rates. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 1632–1644 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02057.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02057.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herfort L, Thake B, Taubner I. 2008. Bicarbonate stimulation of calcification and photosynthesis in two hermatypic corals. J. Phycol. 44, 91–98 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00445.x (doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00445.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider K, Erez J. 2006. The effect of carbonate chemistry on calcification and photosynthesis in the hermatypic coral Acropora eurystoma. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 1284–1293 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marubini F, Ferrier-Pagès C, Furla P, Allemand D. 2008. Coral calcification responds to seawater acidification: a working hypothesis towards a physiological mechanism. Coral Reefs 27, 491–499 10.1007/s00338-008-0375-6 (doi:10.1007/s00338-008-0375-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.dePutron SJ, McCorkle DC, Cohen AL, Dillon AB. 2010. The impact of seawater saturation state and bicarbonate ion concentration on calcification by new recruits of two Atlantic corals. Coral Reefs 30, 321–328 10.1007/s00338-010-0697-z (doi:10.1007/s00338-010-0697-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langdon C, Atkinson MJ. 2005. Effect of elevated pCO2 on photosynthesis and calcification of corals and interactions with seasonal change in temperature/irradiance and nutrient enrichment. J. Geophys. Res. 110, C09S07. 10.1029/2004JC002576 (doi:10.1029/2004JC002576). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zondervan I, Rost B, Riebesell U. 2002. Effect of CO2 concentration on the PIC/POC ratio in the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi grown under light-limiting conditions and different day lengths. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 272, 55–70 10.1016/S0022-0981(02)00037-0 (doi:10.1016/S0022-0981(02)00037-0). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gattuso J-P, Allemand D, Frankignoulle M. 1999. Photosynthesis and calcification at cellular, organismal and community levels in coral reefs: a review on interactions and control by carbonate chemistry. Am. Zoo. 39, 160–183 10.1093/icb/39.1.160 (doi:10.1093/icb/39.1.160) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borowitzka MA. 1981. Photosynthesis and calcification in the articulated coralline red algae Amphiroa anceps and A. foliacea. Mar. Biol. 62, 17–23 10.1007/BF00396947 (doi:10.1007/BF00396947) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Semesi SI, Kangw J, Björk M. 2009. Alterations in seawater pH and CO2 affect calcification and photosynthesis in the tropical coralline alga, Hydrolithon sp. (Rhodophyta). Estuar. Coast Shelf S. 84, 337–341 10.1016/j.ecss.2009.03.038 (doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2009.03.038) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao K, Aruga Y, Asada K, Ishihara T, Akano T, Kiyohara M. 1993. Calcification in the articulated coralline alga Corallina pilulifera, with special reference to the effect of elevated CO2 concentration. Mar. Biol. 117, 129–132 10.1007/BF00346434 (doi:10.1007/BF00346434) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofmann L, Yildiz G, Hanelt D, Bischof K. 2012. Physiological responses of the calcifying rhodophyte, Corallina officinalis (L.), to future CO2 levels. Mar. Biol. 159, 783–792 10.1007/s00227-011-1854-9 (doi:10.1007/s00227-011-1854-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anthony KRN, Kline DI, Diaz-Pulido G, Dove S, Hoegh-Guldberg O. 2008. Ocean acidification causes bleaching and productivity loss in coral reef builders. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 17 442–17 446 10.1073/pnas.0804478105 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0804478105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuffner IB, Andersson AJ, Jokiel PL, Rodgers KS, Mackenzie FT. 2008. Decreased abundance of crustose coralline algae due to ocean acidification. Nat. Geosci. 1, 114–117 10.1038/ngeo100 (doi:10.1038/ngeo100) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diaz-Pulido G, Anthony KRN, Kline DI, Dove S, Hoegh-Guldberg O. 2012. Interactions between ocean acidification and warming on the mortality and dissolution of coralline algae. J. Phycol. 48, 32–39 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2011.01084.x (doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2011.01084.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tambutté E, Tambutté S, Segonds N, Zoccola D, Venn A, Erez J, Allemand D. 2012. Calcein labelling and electrophysiology: insights on coral tissue permeability and calcification. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 19–27 10.1098/rspb.2011.0733 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0733) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furla P, Galgani I, Durand I, Allemand D. 2000. Sources and mechanisms of inorganic carbon transport for coral calcification and photosynthesis. J. Exp. Biol. 203, 3445–3457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen AL, McConnaughey TA. 2003. Geochemical perspectives on coral mineralization. Rev. Mineral Geochem. 54, 151–187 10.2113/0540151 (doi:10.2113/0540151) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Horani FA, Al-Moghrabi SM, De Beer D. 2003. The mechanism of calcification and its relation to photosynthesis and respiration in the scleractinian coral Galaxea fascicularis. Mar. Biol. 142, 419–426 10.1007/s00338-007-0250-x (doi:10.1007/s00338-007-0250-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Venn A, Tambutté E, Holcomb M, Allemand D, Tambutté S. 2011. Live tissue imaging shows reef corals elevate pH under their calcifying tissue relative to seawater. PLoS ONE 6, e20013. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020013 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allemand D, Tambutté E, Zoccola D, Tambutté S. 2011. Coral calcification, cells to reefs. In Coral reefs: an ecosystem in transition (eds Dubinsky Z, Stambler N.), pp. 119–150 Berlin, Germany: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borowitzka MA, Larkum AWD. 1987. Calcification in algae: mechanisms and the role of metabolism. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 6, 1–45 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fabricius KE, et al. 2011. Losers and winners in coral reefs acclimatized to elevated carbon dioxide concentrations. Nat. Clim. Change 1, 165–169 10.1038/NCLIMATE1122 (doi:10.1038/NCLIMATE1122) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pandolfi JM, Connolly SR, Marshall DJ, Cohen AL. 2011. Projecting coral reef futures under global warming and ocean acidification. Science 333, 418–422 10.1126/science.1204794 (doi:10.1126/science.1204794) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edmunds PJ, Brown D, Moriarty V. 2012. Interactive effects of ocean acidification and temperature on two scleractinian corals from Moorea, French Polynesia. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 2173–2183 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02695.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02695.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]