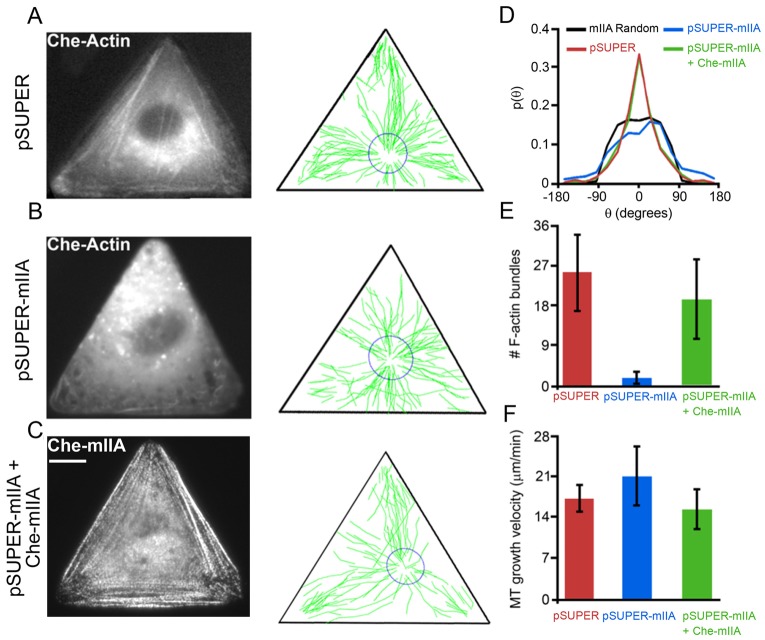

Fig. 6.

Guided growth of MTs toward focal adhesions at the vertices of the triangles requires myosin IIA. (A–C) F-actin bundles [from mCherry–actin live images in A and B or from mCherry–myosin IIA (mChe–mIIA) image in C], and MT growth trajectories (reconstructed from EB3–GFP time-lapse movies) in triangular Rat2 cells transfected with (A) pSUPER (n = 4 cells; 470 trajectories), (B) pSUPER-mIIA (n = 7 cells; 699 trajectories), or (C) pSUPER-mIIA together with RNAi resistant mChe-mIIA DNAs (n = 6 cells; 597 trajectories). (D–F) Quantification of (D) the directions of MT growth trajectories, (E) depletion of F-actin bundles, and (F) MT growth velocities. The knockdown of MIIA with RNAi depletes F-actin bundles and renders MT trajectories disorganized and/or misdirected (note many tracks directed towards the sides of the triangle), an effect rescued by adding back exogenous RNAi-resistant mCherry–mIIA. Scale bar: 10 µm for all images. For the distributions in D, a two-sample t-test shows that the probabilities (at θ = 0°) for cells transfected with pSUPER or pSUPER-mIIA+Che-mIIA are greater than for the random/unguided case at the 99% confidence level. pSUPER-mIIA-transfected cells, however, are statistically similar to the unguided case.