Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the applicability of telediagnosis in oral medicine, through the transmission of clinical digital images by e-mail. Subjects and Methods: The sample included 60 consecutive patients who sought oral medicine services at the Federal University of Paraná, in the state of Paraná, located in southern Brazil. The clinical history and oral lesion images were recorded using clinical electronic charts and a digital camera, respectively, and sent by e-mail to two oral medicine consultants. The consultants provided a maximum of two clinical hypotheses for each case, which were compared with biopsy results that served as the gold standard. Results: In 31 of the 60 cases (51.7%), both consultants made the correct diagnosis; in 17 cases (28.3%), only one consultant made the correct diagnosis; and in 12 cases (20%), neither consultant made the correct diagnosis. Therefore, in 80% of cases, at least one consultant provided the correct diagnosis. The agreement between the first consultant and the gold standard was substantial (κ=0.669), and the agreement between the second consultant and the gold standard was fair (κ=0.574). Conclusions: The use of information technology can increase the accuracy of consultations in oral medicine. As expected, the participation of two remote experts increased the possibility of correct diagnosis.

Key words: medical records, telehealth, telemedicine, telecommunications

Introduction

Teledentistry has been considered as a practical and potentially cost-effective method to provide healthcare to underserved populations, including socially disadvantaged people, those who live in remote or rural areas, and those who lack regular access to routine dental care.1–3 Many medical specialties are investing in telehealth technologies to deliver clinical services to remote areas devoid of human resources for specialized care.4,5 Such tools, however, have been infrequently used as a method of diagnosis, consultation, and referral in dentistry practices.6

Some studies have investigated whether the use of telehealth communication technology and intraoral cameras for visual oral health screenings would be comparable to traditional screenings.4,6,7 Other researchers have developed systems to provide telemedicine consultations for preoperative assessments or follow-up treatments.8–11 Moreover, previous research has evaluated whether patients and clinicians accept telehealth methodologies.5

For example, Rollert et al.8 evaluated a telemedicine consultation system for the preoperative assessment of patients prior to dentoalveolar surgical procedures in an attempt to reduce the costs of conventional appointments. Leão and Porter5 studied patient and clinician acceptability toward recording and transmitting clinical images of common oral diseases via the Internet and aimed to develop and apply this methodology for the distant diagnosis of oral diseases.

Zamzam and Luther12 studied patients with special needs to evaluate relationships among age, lip position, and drooling in children with cerebral palsy. The authors aimed to compare two methods used by specialists to assess lip position: the remote video surveillance technique and direct clinical evaluation. Ewers et al.10 summarized their experiences in applying telemedically supported treatments in craniomaxillofacial surgery and arthroscopic interventions at the University Hospital of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. The authors emphasized that the current state of development allows for the intraoperative application of teleconsultation not only for research purposes, but also in daily clinical routines. In 2008, Nickenig et al.9 developed a study to evaluate telemedicine in implant dentistry and to investigate whether indications and prosthetic objectives could be determined using this tool. Torres-Pereira et al.13 investigated the feasibility of distant diagnosis in oral medicine; their objectives were to study teledentistry via e-mail and to use digital photography to quantify the accuracy of diagnosis by remote specialist consultants. Aziz and Ziccardi11 explored the application of smartphone technology in telemedicine for oral and maxillofacial surgeons. The authors studied 4 cases in which smartphones were successfully used in teledentistry for consultation, communication, and treatment planning.

Pediatric dentistry is also experiencing the benefits of telediagnosis. A group of researchers conducted a sequence of investigations using teledentistry to complete oral screenings in preschool children.6,7 According to the authors, digital images had great potential in identifying dental conditions for referral and treatment, and this technology could be used to facilitate the early diagnosis of dental caries, thus improving access to care for the underserved.6 The presence of tartar, gingivitis, and dental fractures, as well as malocclusions, was also diagnosed remotely, using accessible and low-cost technologies.14

The use of the Internet in telehealth may be a practical means of communication between dental clinicians, thereby improving patient management.4 Considering this information, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the applicability of telediagnosis in oral medicine, through the transmission of digital images by e-mail.

Subjects and Methods

For this study, data were collected from oral clinical examinations and oral digital photographs. The research was approved by the Federal University of Paraná Research Ethics Committee (protocol number CEP/SD 169.SM.44/05-04), and all of the participants gave informed consent. The study was designed with a nonrandomized convenience sample. After approval by the Ethics Committee, the first 60 patients who came to the oral medicine clinic at the Federal University of Paraná who needed a biopsy for a definitive diagnosis were invited to participate. The clinic, located in southern Brazil, specializes in the diagnosis of oral lesions, and patients are referred to it from a metropolitan area with approximately 3 million inhabitants. Most referrals are made by the Brazilian National Public Health System.

Clinical data were recorded on an electronic form, specially designed for the study, and stored as a word processing file. Oral lesions were documented using a digital camera (EOS 300 Rebel; Canon, Tokyo, Japan) with a 100-mm macro lens and a Canon circular flash system. Clinical images were saved as JPEG files and then sent as an e-mail attachment to two consultants. The oral lesion images were 150–500 KB in size, with a minimum resolution of 600 dpi. No specific protocol concerning the number, angles, or views was designed for obtaining clinical images because the protocol depended on the location of the lesion and its size. A 43-cm color monitor was used to visualize the lesions.

Image and text files were renamed with sequential numbers to avoid patient identification. Two distant consultants, both oral medicine specialists, separately analyzed the electronically transmitted images and clinical information. Each consultant recorded a maximum of two clinical hypotheses for each case, which were transmitted electronically. These hypotheses were selected from a predefined list of terms designed to avoid misunderstanding and to establish a predictable basis for data comparison. Both distant consultants had the opportunity to give two possible diagnoses for each case. In oral medicine, even in person, it is very difficult to establish only one correct hypothesis for lesions. Thus, the consultants were able to reproduce what they would face in person when making clinical diagnosis.

In this study, the hypotheses made by the clinical examiner were not considered in the comparisons. All cases required histological examination for definitive diagnosis, and the biopsy specimens were sent to the oral histopathology laboratory of the University Positive Dental Centre in Curitiba, PR, Brazil. Thus, the “gold standard” was always the biopsy results, and one biopsy was sufficient to diagnose each case.

The hypotheses made by the distant consultants were then compared with the histological data to verify the number of correct hypotheses, using a similar methodology reported in a previous study.13 The agreement between the consultants and the “gold standard” was measured by the κ coefficient of agreement. The sensitivity of telediagnosis, which is considered the probability that a test result will be positive when the disease is present (true-positive rate), was also calculated. The specificity, which is considered the probability that a test result will be negative when the disease is not present (true-negative rate), could not be calculated in this study because all of the participants had an oral lesion.

Results

This study evaluated 60 patients, and no technical problems were detected in the store-and-forward system during the study. When the first clinical hypothesis for each case was considered exclusively, consultant 1 made a correct diagnosis in 36 cases (60%), and the agreement between his diagnoses and the gold standard was fair (κ=0.575). Consultant 2 made correct diagnosis in 33 cases (55%), and the agreement between his diagnoses and the gold standard was also considered fair (κ=0.516). When the two clinical hypotheses for each case were considered, there was an increase in the number of correct diagnoses for both consultants. Consultant 1 made 42 correct diagnoses (70%), and the agreement between his diagnoses and the gold standard was now considered substantial (κ=0.669). Meanwhile, consultant 2 made 38 correct diagnosis (63.3%), and the κ coefficient of agreement increased to κ=0.574 (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Frequency of Correct Diagnoses by Consultant 1 Considering One or Two Hypotheses

| CONSULTANT 1 | CORRECT DIAGNOSIS | WRONG DIAGNOSIS | κa | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 hypothesis | 36 (60%) | 24 (40%) | 0.575 | 60 (100%) |

| 2 hypotheses | 42 (70%) | 18 (30%) | 0.669 | 60 (100%) |

Agreement between the consultant and the gold standard.

Table 2.

Frequency of Correct Diagnoses by Consultant 2 Considering One or Two Hypotheses

| CONSULTANT 2 | CORRECT DIAGNOSIS | WRONG DIAGNOSIS | κa | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 hypothesis | 33 (55%) | 27 (45%) | 0.516 | 60 (100%) |

| 2 hypotheses | 38 (63.3%) | 22 (36.7%) | 0.574 | 60 (100%) |

Agreement between the consultant and the gold standard.

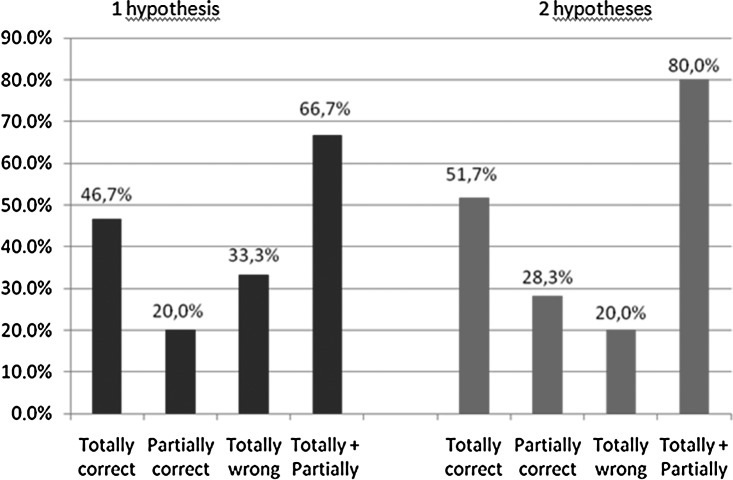

Considering the two hypotheses and the two consultants together, in 31 of the 60 cases (51.7%) both consultants made the correct diagnosis, in 17 cases (28.3%) only one consultant made a correct diagnosis, and in 12 cases (20%) neither consultant made a correct diagnosis. Thus, in 80% of cases, at least one consultant was able to provide the correct diagnosis (Table 3 and Fig. 1). In Table 3, a “totally correct” diagnosis means that both distant consultants gave the correct hypothesis. A “partially correct” diagnosis means that only one distant consultant gave the correct hypothesis. “Total+partial” is the sum of cases in which both consultants made the correct diagnosis plus the cases in which only one made the correct diagnosis. For example, 7 cases were diagnosed with fibrous hyperplasia. In 3 cases, both consultants made the correct diagnosis (totally correct), and in 2 cases, only one made the correct diagnosis (partially correct). Therefore, in 5 cases, at least one consultant was able to provide the correct diagnosis (total+partial diagnosis). In the other two cases, neither of the consultants made the correct diagnosis (wrong) (Figs. 2 and 3). The sensitivity of telediagnosis was 80%.

Table 3.

Final Diagnoses of Oral Lesions and Number of Correct Hypotheses Considering Both Consultants and Two Hypotheses

| FINAL DIAGNOSIS | N | TOTALLY CORRECT | PARTIALLY CORRECT | TOTAL+PARTIAL | WRONG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pleomorphic adenoma | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Oral squamous cell carcinoma | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Salivary gland carcinoma | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Odontogenic cyst | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Peripheral cemento-osseous fibroma | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Fibroma | 7 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 2 |

| Fibrous hyperplasia | 7 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| Hyperkeratosis | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Central giant cell granuloma | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Leiomiossarcoma | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Leukoplakia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Lichen planus | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Peripheral giant cell granuloma | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Mucocele | 7 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 1 |

| Nevus | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Papilloma | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Paracoccidioidomycoses | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Mucous membrane pemphigoid | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Exogenous pigmentation | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Actinic cheilitis | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 60 | 31 | 17 | 48 | 12 |

| Percentage | 100% | 51.5% | 28.3% | 80% | 20% |

Fig. 1.

Frequency of correct diagnosis considering both consultants with one hypothesis and two hypotheses.

Fig. 2.

Fibrous hyperplasia. The similarity with a peripheral cemento-osseous fibroma made the correct diagnosis very difficult (totally incorrect hypothesis).

Fig. 3.

Peripheral cemento-osseous fibroma. The lesion features were sufficiently clear to produce a correct diagnosis (totally correct hypothesis).

Discussion

Although the use of telemedicine has been studied in many medical specialties, there is a lack of consistent evidence for its advantages in dentistry. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the applicability of telediagnosis in oral medicine by transmitting digital images to distant consultants by e-mail. This study demonstrates that two distant consultants giving two diagnoses can provide telediagnosis with a sensitivity of 80%.

According to the methods discussed in the literature, teleconsultation can be conducted in two ways: using the store-and-forward method or by videoconferencing. In the store-and-forward method, data collected from oral clinical examinations, oral digital photography, or digital radiographic images can be stored in an electronic file format, and all of the patient records can be retrieved and reviewed by specialists using the same service. Alternatively, they can be sent via e-mail to another specialist to obtain a second opinion at any time.2,5–7,11–15 In contrast, videoconferences or real-time consultations use direct, online computer telecommunication technologies among specialists, general dental practitioners, telehealth assistants, or patients located in remote communities, with the specialist remaining in a central region to provide support and supervision.1,4,8–10 The majority of studies in the dentistry literature were developed using store-and-forward methodologies, perhaps because these methods are cheaper and demand fewer resources than videoconferencing.

This study was also conducted using the store-and-forward method. The results of this study demonstrate that the consultants made the correct diagnosis in 31 cases (51.7%), only one consultant made a correct diagnosis in 17 cases (28.3%), and both consultants failed to make the correct diagnosis in 12 of 60 cases (20%). Thus in 80% of cases, at least one consultant was able to provide the correct diagnosis. The participation of two consultants as well as the possibility of giving two clinical hypotheses for each case increased the possibility of correct diagnosis, as expected.

These findings are very similar to a previous pilot study conducted by our research group in 2008,13 which investigated the feasibility of distant diagnosis in oral medicine with a methodology similar to that used in the present research. In the previous study, there was complete agreement in 15 of the 25 cases (60%) between the two examiners and the final diagnosis. In 7 of the remaining 10 cases, one consultant made a correct diagnosis. Neither consultant made a correct diagnosis in 3 of the 25 cases (12%). Therefore, in 88% of cases, at least one consultant provided the correct diagnosis in the previous study.

The moderate accuracy in this kind of study may be explained by the heterogeneity of oral diseases in the samples. There is also an inherent difficulty in diagnosing oral diseases, and telediagnosis faces problems similar to those of traditional examination. Moreover, it is relatively common to have a histopathological inconsistency with the clinical diagnosis, even in conventional clinical practice.13

Diagnosing diseases of the head and neck can be particularly problematic for pathologists, and for this reason they should be considered as high-risk diagnostic areas, and second opinions can be helpful for problematic cases.16,17 A previous study evaluated the referral patterns of pathologists to a referral center for oral and maxillofacial pathology to assess changes in diagnosis after receiving a second opinion.18 The authors reviewed pathology consultation requests to determine if there was agreement or disagreement between the original and the second opinion, and they noted the positive impact of a second opinion for lesions in the maxillofacial complex.

A study conducted in 2003 found that interobserver agreement in the clinical and histological assessment of oral lichen planus, defined by κ, varied from poor to moderate and from moderate to substantial, respectively.19 The comparison of the clinical and histopathologic assessment results showed a lack of correlation. These differences may be explained by factors including the choice of biopsy area and the pathologist being unaware of the clinical presentation of lesions.

Moreover, the process by which a pathologist makes a diagnosis is inherently subjective. Factors as diverse as the clinical features of the lesion, professional clinical impression, and the training and experience of the pathologist all play a part in determining the final “sign-out” diagnosis. The pathologist's diagnosis is a necessary part of the process of treating a patient's problem; however, it should be understood by all concerned that variation in opinion exists among pathologists and even within the same pathologist's work.20

Although there appears to be just one similar study in oral medicine for comparison,13 it was possible to identify studies in other fields that allow for comparisons with our results. Prior studies in the field of teledermatology have reported similar results. For example, Piccolo et al.21 found a mean of 85% correct diagnoses using e-mail. Lozzi et al.22 compared teledermatology diagnoses with histopathological examinations and observed a 79% correct distant diagnosis rate. In another dermatology study involving 46 patients, Massone et al.23 reported correct diagnoses in 73% and 74% of cases, compared with the presenting diagnosis and to the histopathological diagnosis, respectively. Complete agreement among teleconsultants was obtained in 20% of the cases.

Information technology could increase the accuracy of consultations because it allows specialists to view and review digital imaging outside of a medical center quickly and easily. Thus, it can improve the efficiency of specialty triaging and the integration of remote experts.

In this study, the “gold standard” was the biopsy result, but it is important to note that histological examination is not always conclusive. There is a wide range of possible diagnoses in oral medicine, and in most cases the final diagnosis is established based on disease history, clinical data, and histological examination. Moreover, the sample of 60 cases is still insufficient to ensure that the protocol for remote diagnosis can replace in-person clinical examinations. In spite of this limitation, there is no doubt that in situations lacking resources for specialized care, this screening tool can improve the flow of referrals to reference centers.

Despite the great evolution of communication technology in the last two decades, studies designed to evaluate teledentistry in systematic ways remain uncommon. It seems reasonable to direct future investigations toward a deeper understanding of this methodology, including the economic impacts on public health, in order to determine the advantages of its applicability on a large scale.

Conclusions

A store-and-forward teledentistry model using e-mail and high-resolution intraoral photographs provides an acceptable index of correct diagnoses, thus endorsing its application as a screening tool for oral diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq) for financial support (grant 38-04 Decit-Ministério da Saúde).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Berndt J. Leone P. King G. Using teledentistry to provide interceptative orthodontic services to disadvantage children. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2008;134:700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT. Billings RJ. Teledentistry in inner-city child-care centres. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12:176–181. doi: 10.1258/135763306777488744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fricton J. Chen H. Using teledentistry to improve access to dental care for underserved. Dent Clin North Am. 2009;53:537–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patterson S. Botchway C. Dental screenings using telehealth technology: A pilot study. J Can Dent Assoc. 1998;64:806–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leão J. Porter S. Telediagnosis of oral disease. Braz Dent J. 1999;10:47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT. Bell CH. Billings RJ. Prevalence of dental caries in early Head Start children as diagnosed using teledentistry. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30:329–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT. Billings RJ. McConnochie KM. Dental screening of preschool children using teledentistry: A feasibility study. Pediatr Dent. 2007;29:209–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rollert MK. Strauss RA. Abubaker AO. Hampton C. Telemedicine consultations in oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:136–138. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(99)90226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nickenig H. Wichmann M. Schlegel A. Eitner S. Use of telemedicine for pre-implant dental assessment—A comparative study. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14:93–97. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2007.070806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ewers R. Schicho K. Wagner A, et al. Seven years of clinical experience with teleconsultation in craniomaxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1447–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aziz SR. Ziccardi VB. Telemedicine using smartphones for oral and maxillofacial surgery consultation, communication and treatment planning. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2505–2509. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zamzam N. Luther F. Comparison of lip incompetence by remote video surveillance and clinical observation in children with and without cerebral palsy. Eur J Orthod. 2001;23:75–84. doi: 10.1093/ejo/23.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torres-Pereira C. Possebon RS. Simões A, et al. E-mail for distance diagnosis of oral diseases: A preliminary study of teledentistry. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14:435–438. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2008.080510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amável R. Cruz-Correia R. Frias-Bulhosa J. Remote diagnosis of children dental problems based on non-invasive photographs—A valid proceeding? Stud Health Technol Inform. 2009;150:458–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandall NA. O'Brien KD. Brady J. Worthington HV. Harvey L. Teledentistry for screening new patient orthodontic referrals. Part 1: A randomized controlled trial. Br Dent J. 2005;199:659–662. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westra WH. Kronz JD. Eisele DW. The impact of second opinion surgical pathology on the practice of head and neck surgery: A decade experience at a large referral hospital. Head Neck. 2002;24:684–693. doi: 10.1002/hed.10105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kronz JD. Westra WH. The role of second opinion pathology in the management of lesions of the head and neck. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;13:81–84. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000156162.20789.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones K. Jordan RCK. Patterns of second-opinion diagnosis in oral and maxillofacial pathology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:865–869. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van der Meij EH. Van der Waal I. Lack of clinicopathologic correlation in the diagnosis of oral lichen planus based on the presently available diagnostic criteria and suggestions for modifications. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:507–512. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbey LM. Kaugars GE. Gunsolley JC, et al. Intraexaminer and interexaminer reliability in the diagnosis of oral epithelial dysplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;80:188–91. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piccolo D. Smolle J. Argenziano G, et al. Teledermoscopy—Results of a multicentre study on 43 pigmented skin lesions. J Telemed Telecare. 2000;6:132–137. doi: 10.1258/1357633001935202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lozzi GP. Soyer HP. Massone C, et al. The additive value of second opinion teleconsulting in the management of patients with challenging inflammatory, neoplastic skin diseases: A best practice model in dermatology? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:30–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Massone C. Soyer HP. Lozzi GP, et al. Feasibility and diagnostic agreement in teledermatopathology using a virtual slide system. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]