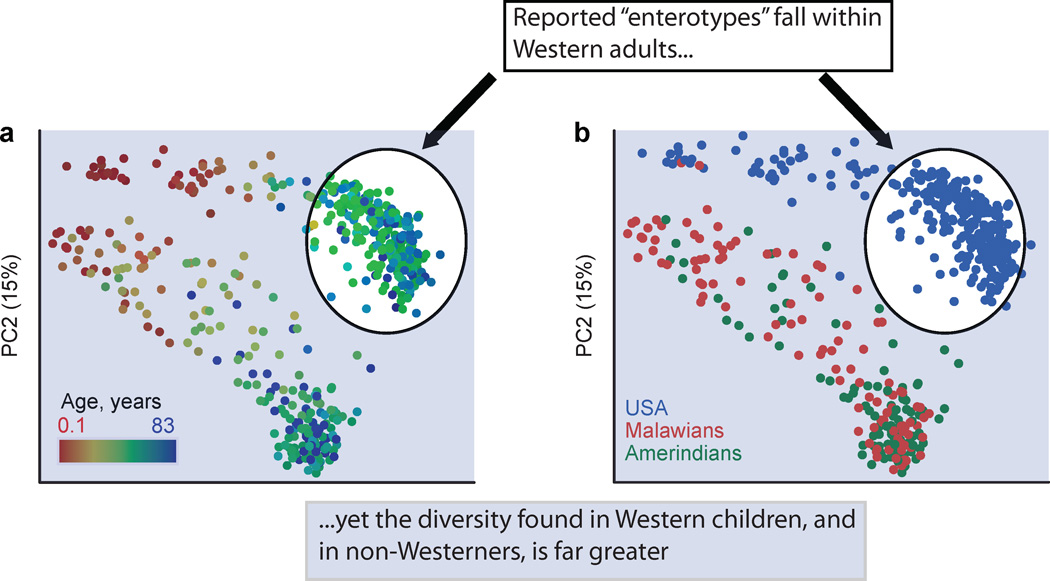

Fig. 5. Human microbial diversity and “enterotypes”.

The reported “enterotypes”31 were determined when evaluating only individuals from the US and Europe, yet including children from the US and children and adults from developing countries greatly expands the picture of human-associated microbiota diversity. We illustrate this here by showing the relationship between the microbiota of 531 healthy infants, children, and adults from Malawi, Venezuelan Amerindians, and the US that were evaluated using sequences from the 16S rRNA gene in fecal samples and a PCoA analysis of unweighted UniFrac distances (adapted from ref. 4 Fig. S2). Microbiota diversity is explained primarily by age (with infants differentiating strongly from adults) and next by culture (with adults from the US having distinct composition compared to adults from Malawi and Venezuelan Amerindians). The points from Western adults are circled in white, and the rest are shaded in blue.