Abstract

Secure parent-child relationships are implicated in children’s self-regulation, including the ability to self-soothe at bedtime. Sleep, in turn, may serve as a pathway linking attachment security with subsequent emotional and behavioral problems in children. We used path analysis to examine the direct relationship between attachment security and maternal-reports of sleep problems during toddlerhood, and the degree to which sleep serves as a pathway linking attachment with subsequent teacher-reported emotional and behavioral problems. We also examined infant negative emotionality as a vulnerability factor that may potentiate attachment-sleep-adjustment outcomes. Data were drawn from 776 mother-infant dyads participating in the NICHD Study of Early Child Care (SECC). In the full sample, after statistically adjusting for mother and child characteristics, including child sleep and emotional and behavioral problems at 24 months, we did not find evidence for a statistically significant direct path between attachment security and sleep problems at 36 months; however, there was a direct relationship between sleep problems at 36 months and internalizing problems at 54 months. Path models that examined the moderating influence of infant negative emotionality demonstrated significant direct relationships between attachment security and toddler sleep problems, and sleep problems and subsequent emotional and behavioral problems, but only among children characterized by high negative emotionality at 6 months of age. In addition, among this subset, there was a significant indirect path between attachment and internalizing problems through sleep problems. These longitudinal findings implicate sleep as one critical pathway linking attachment security with adjustment difficulties, particularly among temperamentally vulnerable children.

Keywords: Sleep, attachment security, emotional and behavioral adjustment, toddler development, negative emotionality

Robust evidence suggests that insecure attachment relationships may increase the risk for internalizing and externalizing problems in children (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010; Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van Ijzendoorn, Lapsley, & Roisman, 2010). Conversely, secure attachments have been shown to promote self-regulatory abilities and adaptive functioning (Gilliom, Shaw, Beck, Schonberg, & Lukon, 2002). Research has focused primarily on associations between attachment security and the child’s developing self-regulation during the daytime and has largely neglected the links between attachment security and the child’s ability to self-regulate at night, both at bedtime and during sleep.

Sleep problems are among the most prevalent, persistent, and salient concerns for parents with children under the age of 3 (Byars, Yolton, Rausch, Lanphear, & Beebe, 2012), as children’s sleep problems can portend increased risk for emotional and behavioral problems in the child (Gregory & O'Connor, 2002; Jansen et al., 2011) and also lead to disruptions in the parents’ sleep, well-being, and the emotional climate of the family (Dahl & El-Sheikh, 2007). Conversely, the emotional climate of the family, and in particular, the security of the attachment relationship may support the child’s ability to self-soothe and self-regulate at night, skills considered to be the hallmark of a good sleeper in early childhood (Mindell, Kuhn, Lewin, Meltzer, & Sadeh, 2006). In Western cultures where co-sleeping with children is not the norm, the sleep period is typically the longest, recurring context in which children have to learn to selfregulate both physiologically and psychologically without the physical presence of the attachment figure. From this perspective, a secure attachment relationship may facilitate young children’s ability to fall into deep and consolidated sleep, by promoting feelings of safety and security and diminishing vigilance and anxiety. In contrast, insecure attachments may heighten vigilance and anxiety and, thereby, interfere with the ability of young children to fall asleep and stay asleep. Teti and colleagues (Teti, Kim, Mayer, & Countermine, 2010) commented that the security of the parent-child relationship in the sleep context may in fact, be even “more salient to socioemotional development than parenting in daytime contexts.”

Attachment and Sleep

Relative to the abundant literature on attachment and daytime self-regulatory processes, only a handful of longitudinal investigations have demonstrated links between insecure attachment and more frequent parent-reported nighttime awakenings during infancy (Beijers, Jansen, Riksen-Walraven, & de Weerth, 2011; McNamara, Belsky, & Fearon, 2003; Morrell & Steele, 2003), with some evidence suggesting that this association becomes stronger as the infant gets older and the attachment relationship consolidates into a stable pattern. For instance, Zentall and colleagues (Zentall, Braungart-Rieker, Ekas, & Lickenbrock, 2012) found that night waking as reported by parents at 7 months of age was unrelated to attachment (measured at 12 months of age). However, at 12 months of age, securely attached infants had fewer parent-reported night-awakenings than their insecure counterparts. In contrast, several cross-sectional studies, using objective measures of infants’ sleep (i.e., actigraphy or video recordings of bedtime interactions) have not found significant differences in sleep patterns as a function of secure versus insecure attachment (Higley & Dozier, 2009; Scher, 2001; Scher & Asher, 2004). Taken together, the pattern of results and inconsistencies across studies, suggests that attachment-sleep associations are most evident for parent-reported sleep problems, rather than objective sleep measures, and may be more likely to emerge over time, particularly beyond the first year of life, when the attachment relationship becomes more fully established and as sleep patterns consolidate. To our knowledge, however, only 4 studies to date have investigated the association between attachment and sleep in children after the first year of life, and these studies focused on substantially later stages of child development, including early school-age and later adolescence (El-Sheikh, Buckhalt, Keller, Cummings, & Acebo, 2007; Keller & El-Sheikh, 2011; Scharfe & Eldredge, 2001; Vaughn et al., 2011). Thus, there remains a substantial gap in the literature pertaining to how attachment-sleep dynamics operate during the toddler period.

Sleep In Toddlerhood

There are several reasons that toddlerhood may represent a particularly important developmental period for considering relationships between attachment and sleep and their impact on subsequent adjustment. Toddlerhood is typically a time when sleep patterns begin to consolidate and become more stable, and most children sleep through the night and on their own (Dahl, 1996). Moreover, several changes in children’s socio-emotional development which occur during toddlerhood may have direct implications for parent-child interactions and for sleep. In particular, during this period, the child becomes more independent, mobile, and verbally communicative, and the attachment relationship becomes established as a goal-corrected partnership (Bowlby, 1969). At the same time, the role of parents becomes more complex, as parents need to balance warmth and support with some degree of limit-setting around routines and expectations (Kochanska, 2002; Thompson, 2000). In toddlerhood, children’s cooperation with parents and their regulation of their own behavior may, therefore, be reflected in adherence to bedtime routines and use of effective self-regulation during the night, making this an especially relevant age to examine links between sleep and attachment security (DeGangi, 2000).

Several longitudinal studies have also demonstrated that parent-reported sleep problems in toddlerhood are associated with increased risk of the subsequent development of anxiety and depression (Gregory, Van der Ende, Willis, & Verhulst, 2008; Jansen et al., 2011) and early onset of alcohol and other substance use in adolescence (Wong, Brower, Fitzgerald, & Zucker, 2004). Thus, toddlerhood may offer a critical window for investigating attachment-sleep dynamics, and for identifying children who continue to have difficulty self-regulating at night, and may ultimately be at greater risk for the later development of emotional and behavioral problems.

Temperament as a Moderator of Attachment-Sleep-Adjustment Outcomes

Infants and toddlers who experience and express high, stable levels of negative emotionality may be especially sensitive to the long-term effects of attachment quality and sleep. Given their tendency to experience and express negative emotionality at lower thresholds, with greater intensity, and with greater frequency than other infants and toddlers, these children may have difficulty self-soothing and might rely more strongly on their relationship with caregivers to provide comfort and support. For such children, the security of the attachment relationship may thus have a stronger impact on sleep than among children who are low in negative emotionality. Supporting this perspective, in a relatively small study of Israeli infants, Scher (2001) found that among securely attached infants, there was no impact of the infants’ fussiness on sleep problems. Similarly, the purported pathways between sleep problems and subsequent emotional and behavioral problems may also be potentiated among young children who experience and express high levels of negative emotionality. For instance, Goodnight and colleagues (Goodnight, Bates, Staples, Pettit, & Dodge, 2007) found that sleep problems measured in childhood (ages 5 to 9) were associated with externalizing behaviors, but only among children who were rated as high in resistance to control in infancy. Taken together, the limited available empirical evidence to support negative emotionality’s role as a moderator highlights the importance of considering in whom associations among attachment, sleep problems, and subsequent emotional and behavioral difficulties are most likely to emerge.

The Present Study

The purpose of the present study was to: (1) investigate the links between attachment security and sleep in toddlerhood, a highly dynamic and under-investigated developmental stage for considering attachment-sleep relationships; (2) examine whether sleep problems in toddlerhood serve as a pathway through which attachment may impact subsequent emotional and behavioral problems evidenced at 54 months of age; and (3) examine in whom connections between attachment-sleep-emotional/behavioral difficulties may be most likely to be manifest. Specifically, we investigated whether the proposed associations between attachment, sleep, and subsequent emotional and behavior problems were stronger among toddlers with reactive temperaments (at 6 months), conceptually defined as high in observed negative emotionality during a positive context, in contrast to those who were low in observed negative emotionality.

Because child and family demographic characteristics and maternal depression have been shown to relate to sleep complaints, attachment security, and/ or children’s emotional and behavioral problems (Adam, Snell, & Pendry, 2007; O'Connor et al., 2007), we examined associations between attachment, sleep, and emotional and behavior problems, over and above the influences of these family factors. Moreover, to provide a stronger test of our hypothesized temporal links between sleep as a pathway linking attachment with subsequent emotional and behavioral problems, we statistically controlled for earlier sleep problems as well as emotional and behavioral problems measured concurrently with attachment (at 24 months).

We predicted that lower levels of attachment security would predict sleep problems one year later, after controlling for sleep problems measured at 24 months. Furthermore, we hypothesized that sleep complaints would, in turn, predict higher levels of emotional and behavioral problems as reported by preschool teachers when children were 54 months of age, after controlling for emotional and behavioral problems as reported by mothers at 24 months. Finally, we predicted that infant negative emotionality would potentiate each of the hypothesized paths in the model. That is, direct and indirect associations between attachment, sleep, and emotional and behavioral problems would be evidenced most strongly in children high in negative emotionality.

Method

Participants

The present study cohort was drawn from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care (NICHD SECC), a large, diverse sample of mother-infant dyads. Families were recruited during hospital visits to mothers shortly after the birth of a child in 1991, at or near the following locations: Little Rock, Arkansas; Irvine, California; Lawrence, Kansas; Boston, Massachusetts; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Charlottesville, Virginia; Morganton, North Carolina; Seattle, Washington; and Madison, Wisconsin (see http://secc.rti.org for a detailed description of study recruitment, data collection, and coding procedures). Informed consent was obtained and each study site adhered to its Institutional Review Board’s guidelines for conducting human research. A diverse sample of 1364 healthy, singletons was enrolled in the study at 1-month: 24% were ethnic minority, 11% of the mothers had not completed high school, and 14% were single.

The sample for the current report included 776 families (57% of the original sample) for whom teacher ratings were available at 54 months and sleep was assessed via maternal report at 24 months (n = 756; 97% of the sample for the current study) and/or 36 months (n = 759; 98% of the sample for the current study). Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all variables of interest for these 776 families. The current sample included 383 boys and 393 girls; 15.7% were of minority ethnicity. Excluded families (n =588) did not differ from included families on maternal depression at 24 months or sleep problems at 36 months. However, included children were less likely to be males (χ2(1) = 3.92, p < .05) or ethnic minorities (χ2(1) = 16.98, p < .05). Furthermore, mothers from included families had approximately one more year of education (t(1361)=−7.72, p<.05), and their children had fewer sleep problems at 24 months (t(1187)= 2.50, p<.05). In addition, included mother-child dyads had higher ratings of attachment security at 24 months (t(1190)= −2.20, p<.05).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Low Negative Emotionality | High Negative Emotionality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | Mean(SD) | Range | N | Mean(SD) | Range | Comparison |

| Maternal Education (in years) | 531 | 14.78(2.40) | 7 to 21 | 232 | 14.54(2.50) | 7 to 21 | t(761) = 1.22 |

| Maternal Depressive Symptoms (24 mos) | 494 | 9.27(8.31) | 0 to 42 | 217 | 9.15(8.52) | 0 to 50 | t(709) = .17 |

| Attachment Security (24 months) | 521 | .30(.21) | −.49 to .73 | 229 | .29(.20) | −.42 to .71 | t(748) = .67 |

| Sleep Problems (24 months) | 516 | 3.05(2.64) | 0 to 13 | 228 | 3.13(2.70) | 0 to 14 | t(742) = −.38 |

| Internalizing Problems (24 months) | 516 | 7.52(4.51) | 0 to 23 | 228 | 8.30(5.32) | 0 to 29 | t(742) =−2.06* |

| Externalizing Problems (24 months) | 516 | 13.84(6.79) | 0 to 37 | 228 | 14.63(7.45) | 0 to 42 | t(742) =−1.42 |

| Sleep Problems (36 months) | 518 | 3.58(2.62) | 0 to 12 | 228 | 3.80(2.59) | 0 to 13 | t (744) =−1.12 |

| Internalizing Problems (54 months) | 531 | 6.88(7.22) | 0 to 46 | 232 | 7.16(6.91) | 0 to 42 | t (761) = −.49 |

| Externalizing Problems (54 months) | 531 | 10.07(11.65) | 0 to 61 | 232 | 10.06(12.22) | 0 to 67 | t (761) = .01 |

p < .05

Overview of Data Collection

Mothers and children were visited in their homes at regular intervals from 1 to 36 months and observed in the laboratory at 24 and 36 months. In addition, at 54 months data were obtained from children’s preschool teachers. Measures in the current report were obtained during these visits at 1, 6, 24, and 36 months and from 54 month teacher reports.

Negative Emotionality

As part of the 6-month home visit, mothers and infants were observed during a 15-minute observation designed to assess mother and child engagement during a typical play interaction with and without toys. The home visit was scheduled for a time when the infant was rested and fed. The interaction was filmed and later coded at a single site by observers unaware of other information about the child and family. Infant negative emotionality was rated on a 4-point scale with 1 indicating no sign of negative mood and 4 indicating a high level of fussiness and distress. Inter-rater reliability was determined on 218 tapes that were coded independently by two observers, previously trained to reliability. The Pearson correlation between pairs of raters on negative emotionality was .83 and the intraclass correlation was .90.

Because the undemanding play situation primarily elicited neutral to positive affect, we considered the expression of negative emotionality to be an unusual response to this context and to reflect stable tendencies to respond to neutral or positive stimuli with more frequent, more intense negative affect. In prior analyses of this data set, this measure of observed negative emotionality at 6 months was associated with later measures of negative and poorly regulated affect during toy clean-up and semi-structured play interactions at 24 and 36 months (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2004), suggesting that behaviors observed during this interaction may capture more stable, meaningful negative emotionality. Consistent with our expectations, scores on this rating were negatively skewed, with most infants displaying no negative emotionality during the observation. Therefore, the scores were dichotomized such that 1 was indicative of no negative emotionality and scores of 2 and above reflected some negative emotion. Based on these criteria, 69.6% of the sample (n = 531) was classified as showing no negative emotionality, and 30.4% of the sample (n = 232) was classified as showing some negative emotion. Thirteen participants were missing data for this variable.

Attachment Security

At 24-months, attachment to the mother was assessed during twohour home visits using the Attachment Q-Sort (AQS; Vaughn & Waters, 1990), a valid indicator of the quality of the mother-child relationship. Observers, trained at each site by Dr. Brian Vaughn, sorted 90 statements from most to least descriptive of the study child’s behavior toward the mother. The resulting score reflected how similar the child was to the “prototypically secure child,” with higher scores indicating a more secure toddler-mother relationship. Prior to data collection, inter-observer reliability was established by having each home visitor (at least two per site) rate five “gold standard” test tapes. The reliability coefficient (intraclass correlation) for this measure was .77. In addition, to maintain reliability during data collection, pairs of home visitors at each site made six visits together and then independently conducted the Q-sort. The Pearson correlation between pairs of raters across the 10 sites was .73.

Sleep Problems

At both 24 and 36 months, mothers completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL 2/3; Achenbach, 1992), which includes a 7-item scale of Sleep Problems. The CBCL sleep problems scale is a widely used and well-validated scale in toddlers (Koot, van den Oord, Verhulst, & Boomsma, 1997), that assesses the most commonly reported sleep complaints presented in pediatric sleep clinics and primary care practices (e.g., Gaylor, Goodlin-Jones, & Anders, 2001). Specifically, the scale includes the following items: resists going to bed at night; doesn’t want to sleep alone; has trouble getting to sleep; wakes up often at night; sleeps less than most children; nightmares; talks or cries out in sleep, rated as “not true” (0), “somewhat or sometimes true” (1), or “very true or often true” (2) of the child. In the current analyses, raw scores were used because they were normally distributed and because <2% of the sample had a Sleep Problems T-score at or above the clinical cut-off score of 70 at 36 months. The Sleep Problems scale demonstrated adequate internal reliability in the present sample (α=.75 at 24 months and α=.70 at 36 months).

Teacher Reports of Children’s Behavior Problems at 54 Months

As part of an extensive assessment of children’s child care or preschool experiences, caregivers/teachers completed the Caregiver-Teacher Report Form for Ages 2–5 of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1986; Achenbach, Edelbrock, & Howell, 1987) at 54 months. To capture emotional and behavioral problems at age 54 months, we utilized, respectively, the broad-band Internalizing scores (based on 34 items assessing anxious, depressed, and fearful behavior) and Externalizing scores (based on 40 items assessing aggressive, disruptive, and inattentive behavior) from the teacher’s observations. Sleep items are not included in the teacher-reported CBCL scores. Raw scores were used in the current analyses.

Covariates

During home interviews at one month, mothers reported their own education (in years), single-parent status (married/ living with a partner vs. single parent), and the study child’s sex and ethnicity. At each interview, mothers completed the CES-D (Radloff, 1977), a reliable and valid 20-item scale that assesses depressive symptoms manifest in the past two weeks. Child sex, child ethnicity, maternal single-parent status, maternal education, maternal depressive symptoms (at 24 months), maternal-reported child sleep problems at 24 months, and maternal-reported internalizing and externalizing problems at 24 months (as assessed with the CBCL 2/3) were used as covariates in the path models.

Analysis Plan

Study hypotheses were examined with a path analytic approach using MPlus 6 (Muthen & Muthen, 2012). Path analysis allowed us to examine direct and indirect relations between attachment, sleep, and children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors at 54 months. Attachment security and covariates, including child ethnicity (minority/majority), child sex, child sleep problems at 24 months, child internalizing and externalizing problems at 24 months, single-parent status, maternal education, and maternal depressive symptoms, were examined as individual manifest exogenous variables. Sleep problems at 36 months were examined as an individual endogenous mediator in the model. For a more parsimonious approach and to account for their influence on each other, teacher-rated internalizing and externalizing behaviors were included as outcomes in a single model with a correlation term included between these outcomes.

Missing data from the sample of 776 were estimated using full information maximum likelihood procedures in MPlus. Overall model fit was examined with multiple fit indices including Chi-square, ratio of Chi-Square to degrees of freedom, RMSEA, CFI, and TLI. Individual paths in the model were also tested for statistical significance. Next, for significant direct paths between attachment and sleep, and sleep and emotional or behavioral problems, we tested the statistical significance of the indirect path between attachment security and emotional or behavioral problems through sleep.

Because we were interested in examining whether the magnitude of associations among attachment security, sleep problems, and behavioral and emotional problems differed at higher and lower levels of negative emotionality, and given the non-normal, highly skewed distribution of the observed infant negative emotionality measure, we examined group invariance in the overall path model. Specifically, an unconstrained model where focal path coefficients (see paths in Figure 1) were allowed to vary across low and high negative emotionality groups was compared with a model where these path coefficients were constrained to be equal (i.e., to test the moderating role of negative emotionality). The chi-square difference test was used to compare the chi-square and degrees of freedom for the two models (unconstrained vs. constrained) to determine whether constraining the focal path coefficients worsened model fit (Byrne, 2004). This approach of estimating separate path models, for the sample as a whole, and separately, for infants high and low in negative emotionality, has the advantage of its computational simplicity and that it produces indices to directly compare the fit and magnitude of effects in each model (Goodnight et al., 2007).

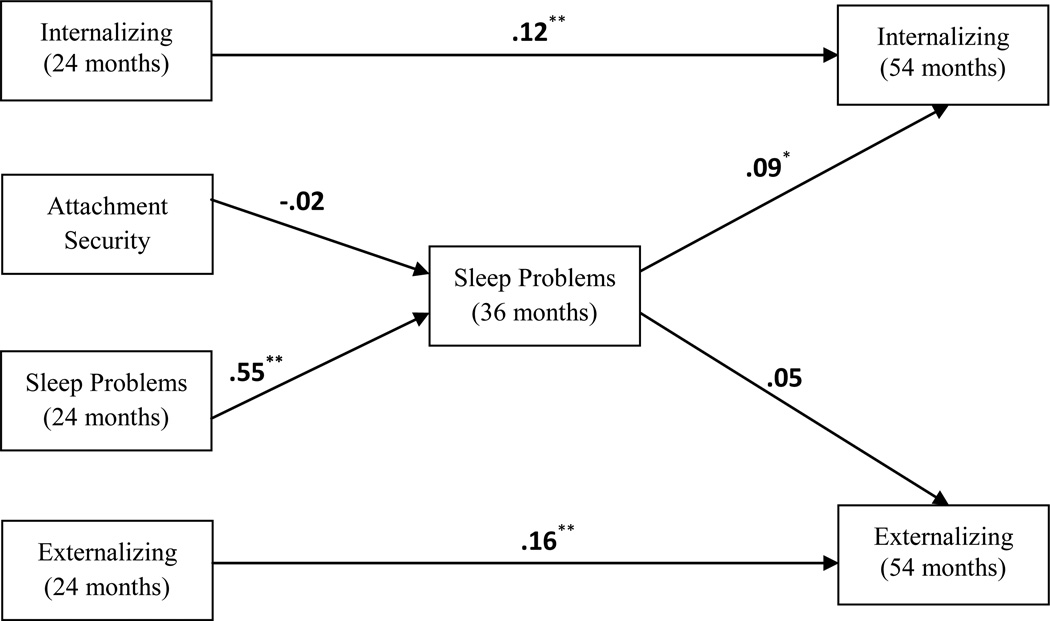

Figure 1.

Model examining predictors of toddler sleep problems using structural equation modeling.

Note. Standardized path coefficients are presented in the figure.

* p < .05. ** p < .01

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive means and standard deviations for each continuous manifest variable as well as the number of participants with data available for each variable, separately for high and low negative emotionality subgroups. This table also includes t-tests comparing the mean levels of each continuous variable between high and low negative emotionality subgroups. None of the t-tests were statistically significant when comparing high and low negative emotionality subgroups, with the exception of the higher mean score for internalizing problems at 24 months in the high negative emotionality subgroup.

Table 2 presents bivariate correlations between all manifest variables. The majority of these correlations were statistically significant. With the exception of positive correlations with single-parent status and internalizing problems at 24 months, negative emotionality was unrelated to other variables in the study, further supporting its role as a potential moderator rather than as a direct predictor of attachment security, sleep problems, or emotional and behavioral problems.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child Sex | ||||||||||||

| 2. Child Race | .04 | |||||||||||

| 3. Maternal Education | .00 | −.24** | ||||||||||

| 4. Single Parent Status | −.02 | .28** | −.27** | |||||||||

| 5. Maternal Depression | .02 | .19** | −.27** | .28** | ||||||||

| 6. Negative Emotionality | −.05 | .01 | −.04 | .11** | −.01 | |||||||

| 7. Attachment Security | .11** | −.15** | .16** | −.15** | −.11** | −.02 | ||||||

| 8. Sleep Problems (24 mos) | −.02 | .06 | −.10** | .14** | .17** | .01 | −.11** | |||||

| 9. Internalizing (24 mos) | .02 | .19** | −.26** | .14** | .29** | .08* | −.17** | .35** | ||||

| 10. Externalizing (24 mos) | −.05 | .12** | −.20** | .12** | .26** | .05 | −.24** | .32** | .72** | |||

| 11. Sleep Problems (36 mos) | .00 | .02 | −.07* | .08* | .19** | .04 | −.09* | .56** | .31** | .28** | ||

| 12. Internalizing (54 mos) | −.02 | .01 | −.13** | .01 | .02 | .02 | −.01 | .07* | .12** | .07* | .13** | |

| 13. Externalizing (54 mos) | −.11** | .08* | −.20** | .14** | .12** | .00 | −.13** | .05 | .11** | .19** | .11** | .51** |

p < .05

p < .01.

Initial Path Model

The model presented in Figure 1 allowed us to examine the hypotheses that 24 month attachment security would directly predict sleep problems at 36 months and that sleep problems would directly predict behavioral outcomes at 54 months (internalizing and externalizing problems). Moreover, the model allowed us to examine the indirect paths from attachment security to behavioral problem outcomes through sleep problems. Covariates included single-parent status, maternal education, maternal depression, child sex, and child ethnicity. Paths were included from each of these covariates to sleep problems at 36 months and to both behavioral outcomes. Child sleep problems at 24 months were also included as a predictor of sleep problems at 36 months. Furthermore, internalizing and externalizing problems at 24 months were included as predictors of internalizing and externalizing problems at 54 months, respectively.

The chi-square goodness of fit index tests exact model fit, and a non-significant chisquare value (i.e., p > .05) supports model fit. Another fit index, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), rewards model parsimony. RMSEA values below .06 support good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Lastly, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) measures the fit of the model in comparison to the absolute fit of a baseline model, and a value above .95 for the CFI indicates good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). With the exception of the statistically significant chi-square value, these fit indices supported good fit for the model in Figure 1, with χ2 (8)= 26.57, p < .05, RMSEA = .055, and CFI = .97.

Standardized parameter estimates for the focal paths are presented in Figure 1. The majority of the paths from the covariates to sleep problems at 36 months and behavioral outcomes at 54 months were non-significant. However, the path from maternal depression to sleep problems at 36 months was positive and statistically significant (β = .11, p < .01), and the path from sleep problems at 24 months to sleep problems at 36 months was highly statistically significant, demonstrating the stability in sleep problems during toddlerhood (β = .55, p < .001). Furthermore, the paths from maternal education to internalizing and externalizing problems were negative and statistically significant (β = −.12, p < .01 and β = −.14, p < .001, when predicting internalizing and externalizing, respectively). Also, child sex predicted externalizing problems such that girls exhibited lower levels of these problems than boys (β = −.10, p < .01). Finally, the respective stability paths from internalizing and externalizing problems at 24 months to these same problems at 54 months were statistically significant (β = .12, p < .01 and β = .16, p < .001, for internalizing and externalizing, respectively).

The path from attachment security to sleep problems at 36 months was non-significant, indicating the attachment insecurity was not associated with later sleep problems in the full sample of 776 when controlling for sleep problems at 24 months and the other covariates. In addition, the path from sleep problems at 36 months to externalizing problems at 54 months was non-significant. However, the path from sleep problems at 36 months to internalizing problems at 54 months was positive and statistically significant (β = .09, p < .05). Because attachment security was not associated with sleep problems at 36 months in this model, we did not investigate the indirect pathway from attachment security at 24 months to internalizing problems at 54 months via sleep problems at 36 months.

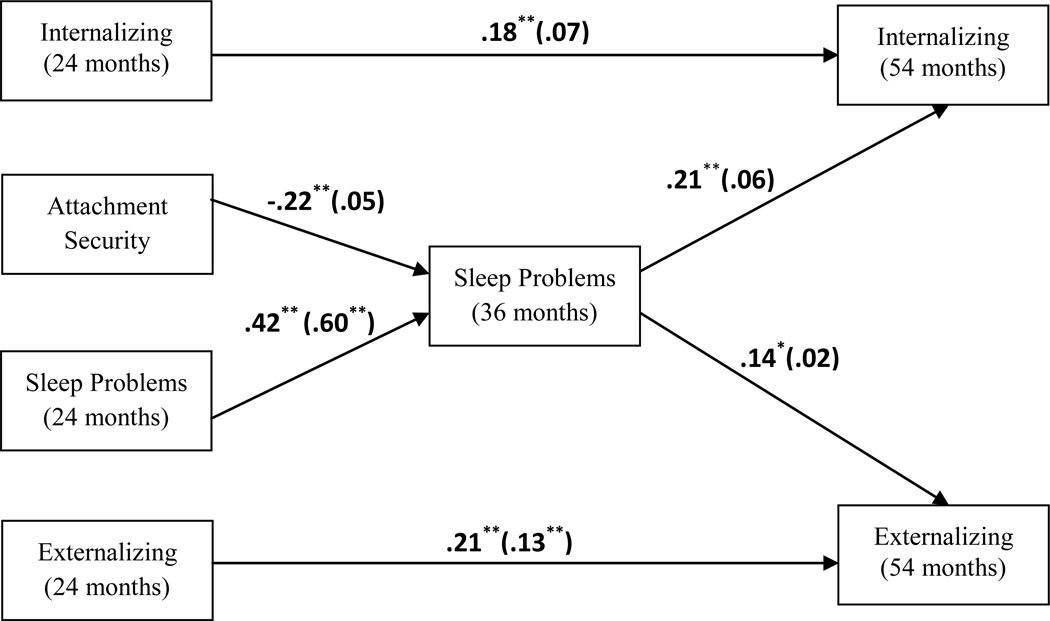

Examining Negative Emotionality as a Moderator

Support was found for a moderating effect of negative emotionality on the model linking attachment security, sleep complaints, and emotional and behavioral problems. When examining negative emotionality as a moderator of the paths shown in Figure 1, the constrained model (which assumes no moderating influence of negative emotionality) had significantly poorer model fit relative to the unconstrained model (Δχ2 = 29.10, Δdf = 6, p < .001). As shown in Figure 2, in the unconstrained model, direct paths from attachment security to sleep problems at 36 months and from sleep problems at 36 months to internalizing and externalizing problems were statistically significant for the high negative emotionality group, but these paths were non-significant for the low negative emotionality group.1 Furthermore, in the high negative emotionality group, predictors in the model explained 9.5% of the variance in internalizing problems at 54 months and 13.2% of the variance in externalizing problems at 54 months. Predictors in the model explained 3.3% of the variance in internalizing problems at 54 months and 7.9% of the variance in externalizing problems at 54 months in the low negative emotionality group.

Figure 2.

Unconstrained model examining infant negative emotionality as a moderator.

Note. Standardized path coefficients are presented in the figure. Path coefficients for the high negative emotionality group are presented first followed by path coefficients for the low negative emotionality group in parentheses.

* p < .05. ** p < .01

Given the significant direct paths between attachment security and sleep problems, and between sleep problems and behavior problems at 54 months in the high negative emotionality group, we evaluated the statistical significance of the focal indirect pathways linking attachment insecurity to behavior problems (internalizing and externalizing) through sleep by using the Model Indirect command in Mplus. The Model Indirect command uses the Delta method (Sobel, 1982) to test the statistical significance of indirect effects. This method provides a significance statistic for the indirect effect of a predictor on an outcome through an intermediate variable (or multiple intermediate variables). When evaluating the unconstrained moderator model, the results of the Delta method supported an indirect path from attachment security to internalizing problems at 54 months via sleep problems at 36 months in the high negative emotionality group (z = −2.40, p < .05). The indirect path from attachment security to externalizing problems at 54 months via sleep problems at 36 months was marginally significant in the high negative emotionality group (z = −1.81, p < .08).

In addition to testing the moderating influence of negative emotionality on the overall model, we also evaluated negative emotionality as a moderator of the six individual paths shown in Figure 2 by comparing separate models that constrained a single path (e.g., attachment security to sleep problems at 36 months) to the unconstrained model. The constrained model had significantly poorer model fit relative to the unconstrained model when constraining the individual paths from attachment to sleep problems at 36 months and continuity of sleep problems from 24 months to 36 months. Furthermore, constraining the path from sleep problems at 36 months to internalizing problems at 54 months led to a marginally significant (p < .07) decrease in model fit. The model constraints for the other three individual paths did not worsen model fit (analyses available upon request).

Discussion

In a large, diverse sample, using measures that included behavioral observations and both maternal and teacher reports, and longitudinal reports of sleep, the present study demonstrated significant direct relationships between attachment security and toddler sleep problems, and sleep problems and subsequent emotional and behavioral problems. In addition, a significant indirect path between attachment and internalizing problems through sleep problems was obtained, but only among infants characterized as being high in negative emotionality. These results indicate stronger associations among attachment and sleep in toddlerhood and subsequent emotional and behavioral problems in children who were high in negative emotionality in infancy, in contrast to those who were low in negative emotionality. This may suggest that when sleep problems occur in the context of both higher levels of negative emotionality and less secure toddler-mother attachment relationships, children are more likely to have continuing difficulties regulating negative emotion; this may be reflected in anxiety and fearfulness and/or aggression and non-compliance at 54 months. One possibility is that sleep problems in toddlerhood are yet another marker of regulatory difficulties among infants high in negative emotionality. Given that there was lesser stability in sleep problems between 24 and 36 months among infants with high negative emotionality, it is also possible that such greater variability may have contributed to the power to detect change in sleep across this developmental period.

These results are consistent with the differential susceptibility hypothesis (Belsky et al., 2007), which suggests that specific temperamental characteristics of the child, including negative emotionality, may render the child more “malleable” or susceptible in the face of either positive (e.g., secure) or negative (e.g., insecure) rearing environments. A secure attachment that supports the development of self-regulatory skills, including the ability to self-soothe at night, may be particularly beneficial for more emotionally labile infants, and may mitigate downstream emotional and behavioral sequelae associated with sleep disturbances. In contrast, infants who are high in negative emotionality and also insecurely attached may not only require greater external support and structure around bedtime and the bedtime routine, but may also be more likely to elicit inconsistent or less sensitive parenting responses. In turn, these insecure children may be even more sensitive to sleep disturbances and subsequent adjustment difficulties. For example, Teti and colleagues (2010) found that parent’s emotional availability during nighttime interactions was more predictive of infant night waking than specific parenting behaviors (e.g., contact). Thus, in the context of an insecure attachment, children who are high in negative emotionality may be particularly sensitive to the parents’ emotional unavailability, which may in turn further diminish their ability to self-soothe at night. On the other hand, the current findings suggest that young children with high levels of negative emotionality may be particularly likely to benefit from a secure attachment relationship and the resultant emotional availability during nighttime interactions.

Although some previous studies have shown direct links between temperament and sleep problems concurrently (Goodnight et al., 2007) or as a predictor of sleep problems in toddlerhood (Morrell & Steele, 2003), the associations are generally small in magnitude. Moreover, consistent with our findings, several studies have found no direct relationships between temperament and sleep (e.g., Keener, Zeanah, & Anders, 1988; Scher, Tirosh, & Lavie, 1998). The equivocal nature of results may reflect several methodological differences across studies, including sample selection (clinical versus community-based samples), definition and measurement of temperament and sleep (e.g., maternal report versus objective or observational assessments), and developmental differences which are relevant for both temperament and sleep-wake regulation.

The measure of infant negative emotionality used in the current study was based on observations of infant fussiness and distress during a low demand mother-infant play interaction. Thus, this observational measure of temperament has the advantage of reducing potentially spurious associations between temperament and sleep, when both constructs are assessed via maternal report. However, we acknowledge that this measure provides a somewhat limited assessment of infant negative emotionality. In addition, based on the highly skewed, non-normal distribution, we dichotomized the sample into high and low negative emotionality groups, which may have reduced power to detect statistically significant direct paths. Future studies employing cross-context and cross-time observations as well as parent report are necessary to provide a more comprehensive assessment of negative emotionality.

Consistent with previous literature, sleep problems in toddlerhood predicted higher levels of teacher-reported internalizing behaviors and externalizing behaviors at age 54 months. The extensive literature on insomnia and affective disorders conceptualizes sleep problems as both co-occurring with and presaging depression and anxiety disorders (as reviewed in Chorney, Detweiler, Morris, & Kuhn, 2008), and this appears to be the case in early development as well as in adulthood (Perlis, Giles, Buysse, Tu, & Kupfer, 1997). Goodnight and colleagues (2007) demonstrated stronger links between sleep problems and externalizing behaviors among children who were characterized as being high in resistance to control in infancy (as assessed by maternal retrospective report). Our findings extend this literature by demonstrating that an observed measure of infant negative emotionality was a key moderator of longitudinal relationships between attachment, sleep in toddlerhood, and emotional and behavioral problems at age 54 months. Notably, the stronger associations we observed in our overall model when including the influence of negative emotionality was particularly striking for the link between sleep problems and internalizing problems. This suggests that a stable tendency toward experiencing and expressing negative affect enhances the contribution of sleep problems to later affective problems.

The fact that longitudinal associations between earlier attachment and sleep and later emotional and behavioral problems (as reported by preschool teachers) emerged even after accounting for the effects of maternal depressive symptoms, demographic characteristics, and earlier sleep and emotional and behavioral problems, suggests that the emotional quality of the mother-child relationship, especially in interaction with infant negative emotionality, is more than a proxy for other co-occurring, known risk factors for sleep complaints. Secure parent-child relationships could enhance the child’s emotional security through the child’s experience of a positive, loving relationship with a parent; the flexible, adaptive emotional functioning of a parent who is sensitive to interpersonal cues; or the early foundations of a strong, supportive parent-child relationship. Furthermore, attachment security might also influence children’s sleep via its role in contributing to family stability and harmony, which may, in turn, facilitate healthy sleep behaviors, including establishing regular bedtime routines and maintaining consistent sleep-wake schedules. Healthy sleep, in turn, may be reflected in young children’s ability to regulate mood and behavior at 54 months of age.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current findings must be considered in light of several methodological limitations. We focused on children’s attachment to mothers, and while this construct is postulated to play an important role in the child’s social functioning, it is also wise to consider attachment to fathers and other important caregivers. In addition, the sample was generally middle class (even more so than the larger sample from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care) and had higher levels of attachment security than the larger NICHD cohort, which may have reduced statistical power to detect significant path relationships. Although the results support our directional hypothesis that attachment may influence subsequent sleep problems, particularly given that we statistically controlled for sleep measured at 24 months, we cannot rule-out the possibility of the reverse pathway (i.e., sleep problems leading to differences in attachment security). Previous longitudinal investigations lend further support to the contention that the pathway leading from attachment to sleep problems is stronger than the reverse (e.g., Keller & El-Sheikh, 2011; Zentall et al., 2012). Alternatively, shared genetic factors may contribute to parent-child dynamics, toddler sleep problems, and later emotional and behavioral problems among temperamentally-vulnerable children. It will be critical for future studies of childhood sleep to examine the potential dynamic relationships between sleep and parent-child relationship characteristics, in interaction with other contextual factors, at the level of the child, family, and broader socio-cultural context.

Finally, findings must be interpreted within the context of measurement limitations, specifically with regard to maternal reports of sleep problems. Although there are limited data suggesting that maternal reports of child sleep problems on the CBCL correlate with specific behavioral (i.e., actigraphic) measures of sleep (Aronen, Paavonen, Fjallberg, Soininen, & Torronen, 2000), in general, the correlations between CBCL sleep and actigraphy are modest (Gregory et al., 2011). The lack of correlation between maternal reports and behaviorally-assessed sleep does not necessarily reflect an inherent lack of validity of the former, more subjective assessment, but rather suggests that the assessments measure different aspects of child sleep-wake regulation. Specifically, maternal reports are likely a better reflection of the types of behaviors that parents are likely to see/ hear from the child (e.g., difficulty settling, difficulty maintaining sleep), whereas, actigraphy or other objective measures (e.g., polysomnography) provide a more accurate assessment of less observable, physiological characteristics of sleep (e.g., sleep latency, sleep architecture, nighttime arousals which are not accompanied by child distress). By the same token, the diagnosis of insomnia, the most common sleep disorder in adults, is assessed not by polysomnography or actigraphy, but rather by subjective reports of sleep difficulty. Sleep problems were based on elevations in maternal reports of sleep problems on the CBCL Sleep Problems scale. However, given that less than 2% of the sample had T-scores above the clinical cut-off on this scale, the raw scores and their association with attachment security cannot be interpreted as clinically relevant sleep disturbances. Nevertheless, given the high stability in sleep problems during the toddler period, it is noteworthy that significant direct and indirect paths between attachment, sleep, and subsequent emotional and behavioral problems emerged even after controlling for sleep problems at 24 months for infants high in negative emotionality.

Previous research suggests that maternal factors, including depressed mood and poor sleep quality, may bias reports of toddler sleep problems (e.g., Loutzenhiser, Ahlquist, & Hoffman, 2011; Meltzer & Mindell, 2007). However, our results are strengthened by the fact that we controlled for maternal depression and utilized observational measures of child temperament and teacher-reported emotional and behavioral problems. In addition, the use of multi-informant methods, including teacher reports of child emotional and behavioral problems, lends further support to the predictive validity of maternal-reported sleep problems at 24 and 36 months. Clearly, future studies utilizing objective (e.g., actigraphy) as well as subjective measures of children’s napping and nighttime sleep can provide a more nuanced assessment of the association between social factors and children’s sleep-wake patterns. In addition, while parentreported sleep likely reflects the importance of self-regulation of sleep, development in physiological mechanisms of sleep throughout childhood could be another source of sleep problems and another contributor to temperament-sleep-adjustment relations.

These limitations notwithstanding, this study offers a unique opportunity to investigate longitudinal associations between attachment, sleep, and subsequent emotional and behavioral problems, across a developmental span from infancy through early childhood, and in a large, diverse community-based sample recruited from across the United States. Moreover, the study’s use of multi-modal assessment of key study constructs (including observational methods and teacher reports) and statistical control for relevant confounding factors, reduces the likelihood of spurious associations due to shared method variance, and highlights the dynamic relationship between early parent-child relationships, sleep, and subsequent child adjustment.

Research on pediatric sleep problems can be valuably informed by consideration of early social and developmental factors that support healthy sleep, as well as links between sleep and later mood and behavior problems. Sleep plays an important role in the development of affect regulation during childhood and adolescence. Poor sleep in early childhood could have a particularly important influence on the onset of affective problems such as depression and anxiety, and behavior problems, such as hyperactivity, inattention, and conduct problems. Because sleep problems in early childhood can affect and are affected by the socioemotional climate of the family, further research is needed to understand the dynamic interplay between characteristics of the parent-child relationship, the family emotional climate, and characteristics of the child, in the broader sociocultural context. Furthermore, a deeper understanding of the emotional and behavioral problems associated with toddler sleep problems could inspire early family-focused interventions that target sleep within the family context in order to improve later affective and behavioral functioning.

Acknowledgements

These data were collected under the auspices of the NICHD Study of Early Child Care. Susan B. Campbell was an investigator on this multi-site study. We acknowledge the generous support of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant HD25420). We also thank the investigators who designed the larger study, the site coordinators and research assistants who collected the data, and the children, parents, child care providers, and teachers who participated in this longitudinal study. Support for the first author (W.M.T) was provided by K23 HL093220. Support for Dr. Trentacosta was provided by K01 MH082926. Support for Dr. Forbes was provided by MH074769.

Footnotes

We re-ran the path models presented in Figures 1 and 2 while winsorizing outliers for internalizing and externalizing problems at 24 and 54 months. Significant pathways remained the same, with the exception of the path from sleep problems to externalizing problems in the high negative emotionality group. This path became marginally significant.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/2-3 and 1992 profile. (1 ed.) 1992 [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C, Howell CT. Empirically based assessment of the behavioral/emotional problems of 2- and 3- year-old children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1987;15(4):629–650. doi: 10.1007/BF00917246. doi:10.1007/BF00917246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam EK, Snell EK, Pendry P. Sleep timing and quantity in ecological and family context: a nationally representative time-diary study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(1):4–19. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.4. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronen ET, Paavonen EJ, Fjallberg M, Soininen M, Torronen J. Sleep and psychiatric symptoms in school-age children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(4):502–508. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00020. doi:10.1097/00004583-200004000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beijers R, Jansen J, Riksen-Walraven M, de Weerth C. Attachment and infant night waking: a longitudinal study from birth through the first year of life. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2011;32(9):635–643. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318228888d. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e318228888d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Steinberg LD, Houts RM, Friedman SL, DeHart G, Cauffman E, et al. Family rearing antecedents of pubertal timing. Child Development. 2007;78(4):1302–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01067.x. .doi:CDEV1067 [pii];10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss, Vol. I: Attachment. London: Hogarth Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Brumariu LE, Kerns KA. Parent-child attachment and internalizing symptoms in childhood and adolescence: a review of empirical findings and future directions. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(1):177–203. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byars KC, Yolton K, Rausch J, Lanphear B, Beebe DW. Prevalence, Patterns, and Persistence of Sleep Problems in the First 3 Years of Life. Pediatrics. 2012 doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0372. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Testing for Multigroup Invariance Using AMOS Graphics: A Road Less Traveled. Structural Equation Modeling A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2004;11(2):272–300. doi:10.1207/s15328007sem1102_8. [Google Scholar]

- Chorney DB, Detweiler MF, Morris TL, Kuhn BR. The interplay of sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression in children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33(4):339–348. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm105. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsm105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE. The regulation of sleep and arousal: Development and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:3–27. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006945. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE, El-Sheikh M. Considering sleep in a family context: introduction to the special issue. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(1):1–3. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGangi G. Pediatric disorders of regulation in affect and behavior: A therapist's guide to assessment and treatment. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Buckhalt JA, Keller PS, Cummings EM, Acebo C. Child emotional insecurity and academic achievement: the role of sleep disruptions. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(1):29–38. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.29. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon RP, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Lapsley AM, Roisman GI. The significance of insecure attachment and disorganization in the development of children's externalizing behavior: a meta-analytic study. Child Development. 2010;81(2):435–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01405.x. doi:CDEV1405 [pii];10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylor EE, Goodlin-Jones BL, Anders TF. Classification of young children's sleep problems: a pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(1):61–67. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00017. doi:S0890-8567(09)60816-9 [pii];10.1097/00004583-200101000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliom M, Shaw DS, Beck JE, Schonberg MA, Lukon JL. Anger regulation in disadvantaged preschool boys: Strategies, antecedents, and the development of self-control. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(2):222–235. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnight JA, Bates JE, Staples AD, Pettit GS, Dodge KA. Temperamental resistance to control increases the association between sleep problems and externalizing behavior development. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(1):39–48. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, Cousins JC, Forbes EE, Trubnick L, Ryan ND, Axelson DA, et al. Sleep items in the child behavior checklist: a comparison with sleep diaries, actigraphy, and polysomnography. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(5):499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.02.003. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, O'Connor TG. Sleep problems in childhood: a longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioral problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(8):964–971. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00015. doi:10.1097/00004583-200208000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, Van der Ende J, Willis TA, Verhulst FC. Parent-reported sleep problems during development and self-reported anxiety/depression, attention problems, and aggressive behavior later in life. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162(4):330–335. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.4.330. doi:162/4/330 [pii];10.1001/archpedi.162.4.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higley E, Dozier M. Nighttime maternal responsiveness and infant attachment at one year. Attachment & Human Development. 2009;11(4):347–363. doi: 10.1080/14616730903016979. doi:10.1080/14616730903016979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen PW, Saridjan NS, Hofman A, Jaddoe VWV, Verhulst FC, Tiemeier H. Does Disturbed Sleeping Precede Symptoms of Anxiety or Depression in Toddlers? The Generation R Study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2011;73(3):242–249. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820a4abb. doi:10.1097/?PSY.0b013e31820a4abb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keener MA, Zeanah CH, Anders TF. Infant temperament, sleep organiztion and nighttime parental interventions. Pediatrics. 1988;81:762–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller P, El-Sheikh M. Children's emotional security and sleep: longitudinal relations and directions of effects. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52(1):64–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02263.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Committed compliance, moral self, and internalization: a mediational model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(3):339–351. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koot HM, van den Oord E, Verhulst FC, Boomsma DI. Behavioral and emotional problems in young preschoolers: cross-cultural testing of the validity of the child behavior checklist/ 2-3. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25(3):183–196. doi: 10.1023/a:1025791814893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loutzenhiser L, Ahlquist A, Hoffman J. Infant and maternal factors associated with maternal perceptions of infant sleep problems. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2011;29(5):460–471. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara P, Belsky J, Fearon P. Infant sleep disorders and attachment: Sleep problems in infants with insecure-resistant versus insecure-avoidant attachments to mother. Sleep and Hypnosis. 2003;5(1):17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer LJ, Mindell JA. Relationship between child sleep disturbances and maternal sleep, mood, and parenting stress: A pilot study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:67–73. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell JA, Kuhn B, Lewin DS, Meltzer LJ, Sadeh A. Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006;29(10):1263–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell J, Steele H. The role of attachment security, temperament, maternal perception, and care-giving behavior in persistent infant sleeping problems. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2003;24(5):447–468. doi:10.1002/imhj.10072. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen L, Muthen B. Mplus 4.0 (Statistical Program) 2012 [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Affect dysregulation in the mother-child relationship in the toddler years: Antecedents and consequences. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:43–68. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor TG, Caprariello P, Blackmore ER, Gregory AM, Glover V, Fleming P. Prenatal mood disturbance predicts sleep problems in infancy and toddlerhood. Early Human Development. 2007;83(7):451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.08.006. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis ML, Giles DE, Buysse DJ, Tu X, Kupfer DJ. Self-reported sleep disturbance as a prodromal symptom in recurrent depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1997;42(2–3):209–212. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(96)01411-5. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(96)01411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977 Sum;1(3):385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306. [Google Scholar]

- Scharfe E, Eldredge D. Associations Between Attachment Representations and Health Behaviors in Late Adolescence. Journal of Health Psychology. 2001;6(3):295–307. doi: 10.1177/135910530100600303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher A. Attachment and sleep: a study of night waking in 12-month-old infants. Developmental Psychobiology. 2001;38(4):274–285. doi: 10.1002/dev.1020. doi:10.1002/dev.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher A, Asher R. Is attachment security related to sleep-wake regulation? Mothers' reports and objective sleep recordings. Infant Behavior & Development. 2004;27:288–302. doi:10.1016/S0163-6383(04)00034-7. [Google Scholar]

- Scher A, Tirosh E, Lavie P. The relationship between sleep and temperament revisited: Evidence for 12-month-olds: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39(5):785–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptomatic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, Kim B, Mayer G, Countermine M. Maternal emotional availability at bedtime predicts infant sleep quality. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(3):307–315. doi: 10.1037/a0019306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. The legacy of early attachments. Child Development. 2000;71(1):145–152. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn BE, El-Sheikh M, Shin N, Elmore-Staton L, Krzysik L, Monteiro L. Attachment representations, sleep quality and adaptive functioning in preschool age children. Attachment & Human Development. 2011;13(6):525–540. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2011.608984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn BE, Waters E. Attachment behavior at home and in the laboratory: Q-sort observations and strange situation classifications of one-year-olds. Child Development. 1990;61(6):1965–1973. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb03578.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb03578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Brower KJ, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Sleep problems in early childhood and early onset of alcohol and other drug use in adolescence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28(4):578–587. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000121651.75952.39. doi:00000374-200404000-00009 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zentall SR, Braungart-Rieker JM, Ekas NV, Lickenbrock DM. Longitudinal assessment of sleep-wake regulation and attachment security with parents. Infant and Child Development. 2012 doi:10.1002/icd.1752. [Google Scholar]